Business

Column: Molly White's message for journalists going freelance — be ready for the pitfalls

Molly White is the model of an indefatigable and intrepid journalist. Through her website Web3 is Going Just Great and newsletter Citation Needed, she keeps tabs on the hacks, scams, failures, hype and assorted legal difficulties swirling about the cryptocurrency world.

She’s also independent, which means she’s unprotected by the fortification of lawyers and resources erected by the owners of newspapers such as The Times to fend off legal threats, frivolous and otherwise, that are part of the arsenal of people and firms we write about.

So she has some advice for journalists tempted by the burden of having bosses to “just go independent,” enticed, say, by the siren call of freelancing: “Just do a substack! It’s the future of journalism.”

I am the legal team. I am the fact-checking department. I am the editorial staff. I am the one responsible for triple-checking every single statement I make in the type of original reporting that I know carries a serious risk of baseless but ruinously expensive litigation regularly used to silence journalists, critics, and whistleblowers.

— Molly White

White’s warning is, in a nutshell: “It’s not for everyone.”

Anyone who follows crypto scams is familiar with White’s work. A software engineer by training, she is a longtime Wikipedia editor who got interested in the dark underbelly of crypto when she tried to write a Wikipedia article about it.

She doesn’t find much if anything to like about the field, which she sees as a hive of people aiming to take advantage of the innocent and unwary — the facetious subtitle of her Web3 website calls it “definitely not an enormous grift that’s pouring lighter fluid on our already smoldering planet.”

But she does it all by herself.

“As an independent writer and publisher,” White wrote recently, “I am the legal team. I am the fact-checking department. I am the editorial staff. I am the one responsible for triple-checking every single statement I make in the type of original reporting that I know carries a serious risk of baseless but ruinously expensive litigation regularly used to silence journalists, critics, and whistleblowers…. I am the one who ultimately could be financially ruined by such a lawsuit. I am the one in charge of weighing whether I should spring for the type of insurance that is standard fare for big outlets to protect themselves and their staff, but often prohibitively expensive for independent writers.”

In recent weeks, White has had to fend off a couple of fatuous legal threats stemming from her work — one from a putative lawyer demanding that she take down a post for infringing a copyright under the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (it wasn’t an infringement), and some sinister legalistic-sounding noise from the crypto platform Coinbase. We’ll return to both in a moment.

Experts in the potholes and pitfalls facing writers — especially investigation-minded or merely activist journalists — say they’ve received a rising number of inquiries from those considering launching a freelance career. Lloyd Jassin, a New York lawyer specializing in publishing law — including copyright and libel law, among other issues important to independent writers — says he’s referred several clients to brokers who represent insurance firms for writers in the last few months.

Curiosity about the freelance life is rising for several reasons. Mass layoffs in the media industry have put thousands of journalists on the street, forcing them to ponder new ways to exercise their professional skills.

Substack and other such platforms purport to offer writers a way to acquire followers of their own, building their personal brands. And the performance of established news media in the recent election, including the decision of the owners of The Times and the Washington Post not to endorse a presidential candidate, may have inspired established staffers to consider an exit from corporate media.

Independent writers’ works are protected, if theoretically, by U.S. libel laws, which discourage defamation lawsuits by public figures, and by so-called SLAPP laws, which discourage “strategic lawsuits against public participation” — that is, lawsuits designed chiefly to intimidate or silence critics. But exercising one’s rights under those laws can require hiring a lawyer, sometimes at considerable expense. Plaintiffs deemed to have filed a SLAPP lawsuit can be required to cover the defendant’s legal costs, but that would happen only after motions in court.

White is no stranger to efforts to intimidate her. The most concentrated pushback she has received recently has come from Coinbase. The crypto platform is irked at White’s reporting that it may have violated federal law by making political contributions while negotiating for and subsequently holding a federal contract.

In conjunction with the watchdog group Public Citizen, White filed a formal complaint against Coinbase with the Federal Election Commission on Aug. 1. In her reporting, White has shown that some of its contributions to the crypto industry super PAC Fairshake were made within the period in which political contributions are barred, which extends from the start of a contributor’s contract negotiations through the completion of the contract. The U.S. Marshals Service awarded Coinbase the $7-million, one-year contract to help manage the government’s hoard of seized crypto assets in July.

Coinbase hasn’t responded directly to White. Its response to the accusation has come through a series of tweets by its chief legal officer, Paul Grewal.

The gist of Grewal’s argument is that the funding for Coinbase’s contract comes from seized crypto assets in the Justice Department’s Assets Forfeiture Fund, not from congressional appropriations. Therefore, he contends, Coinbase didn’t violate the law prohibiting political contributions by contractors paid from “funds appropriated by the Congress.”

“Seized crypto assets are not Congressionally appropriated funds, period,” Grewal wrote.

As it happens, the legal question is far from being so cut and dried. In fact, the definition of “appropriated” was settled conclusively by the Supreme Court, in a 7-2 decision handed down in May and written by Justice Clarence Thomas. The only dissenters were justices Samuel A. Alito Jr. and Neil M. Gorsuch.

In that case, the justices turned away a challenge to the funding of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, which derives from the Federal Reserve System. (The plaintiffs made an elaborately legalistic argument that such funding violates the “appropriations clause” of the Constitution and therefore the CFPB is unconstitutional.)

Thomas wrote that the plaintiffs had offered “no defensible argument” that the appropriations clause requires more than a congressional law authorizing “the disbursement of specified funds for identified purposes,” as was the funding for the CFPB.

By extension, so is the funding for the Coinbase contract. Indeed, the Congressional Research Service, in a close examination of the Assets Forfeiture Fund in 2015, found that for most purposes, the fund was the beneficiary of “a permanent appropriation” by Congress.

Grewal went further. Noting that he had placed his interpretation of the law on the record, he wrote that “repeating misrepresentations of facts after previously being put on notice is …. unwise.”

That sinister ellipsis is Grewal’s.

Grewal told me by email that no legal threat was implied by his tweet, and that Coinbase “certainly would make plain if it were our intent” to progress to a lawsuit.

Still, White interpreted Grewal’s tweet as “certainly a threat of something. I don’t think Coinbase is going to come and break my kneecaps, so a legal threat is the most obvious interpretation. It seems like a pretty clear threat to stop writing about this, or else.”

Public Citizen is sanguine about Coinbase’s swaggering. “Whenever corporate misconduct is pointed out, they always say ‘We didn’t really break the law, or the law doesn’t apply to us the way you think it does,’” says Rick Claypool, a research director at Public Citizen who co-filed the complaint with White. “It would be surprising if they said, ‘Oh, yeah, you’re right, whoops.’ Going up against a Goliath, they have a lot of strength to squish the Davids coming after them.”

Separately, White fielded a “takedown” notice from supposed representatives of Roman Ziemian, a co-founder of the alleged crypto pyramid scheme FutureNet. In an Aug. 19 post on Web3 is Going Just Great, White posted news reports that Ziemian had been arrested in Montenegro, and that he faces international warrants from authorities in Poland and South Korea.

The representatives tried to bribe her $500 to take down the post. When she refused, they copied the post to a blogging website, backdated it, and then claimed she had plagiarized it in an example of copyright infringement. She posted the notice, which came from a purported lawyer named Michael Woods with a Los Angeles address that doesn’t exist in Postal Service records. He didn’t respond to a message I left at the telephone number he listed.

How can independent journalists keep intimidation efforts like these at arm’s length? The goal of those threatening legal action, no matter how frivolous, is “to suppress criticism,” Jassin says. “Being a good journalist is the first defense,” he adds, so getting the facts right is indispensable.

White doesn’t keep a lawyer on retainer, but she knows lawyers who are “willing to glance at something I’ve received in my email inbox and reach out to offer support should one of those threats escalate into something more tangible” — which hasn’t yet happened.

“In a perfect world, reporting the facts would be enough to avoid frivolous lawsuits,” she told me. “But obviously, companies and people with resources are willing to file frivolous lawsuits regardless. That is a risk I take on, with hopes that being cautious and being very careful about fact-checking will at least stave off the worst.”

She advises journalists thinking about going independent to “think through if it would be life-altering to be on the risky end of an actual lawsuit.” There are ways, she notes, to “structure your business so you’re not risking your personal assets,” including finding insurance to cover one’s legal defense.

“Legal threats are only one component” of life as a freelancer. “There are a lot of other challenges — you don’t have employer-sponsored healthcare, or a 401k. A lot of readers think it’s an easy decision to quit a job and go independent. But despite all the challenges, I really love being independent.”

Business

How the S&P 500 Stock Index Became So Skewed to Tech and A.I.

Nvidia, the chipmaker that became the world’s most valuable public company two years ago, was alone worth more than $4.75 trillion as of Thursday morning. Its value, or market capitalization, is more than double the combined worth of all the companies in the energy sector, including oil giants like Exxon Mobil and Chevron.

The chipmaker’s market cap has swelled so much recently, it is now 20 percent greater than the sum of all of the companies in the materials, utilities and real estate sectors combined.

What unifies these giant tech companies is artificial intelligence. Nvidia makes the hardware that powers it; Microsoft, Apple and others have been making big bets on products that people can use in their everyday lives.

But as worries grow over lavish spending on A.I., as well as the technology’s potential to disrupt large swaths of the economy, the outsize influence that these companies exert over markets has raised alarms. They can mask underlying risks in other parts of the index. And if a handful of these giants falter, it could mean widespread damage to investors’ portfolios and retirement funds in ways that could ripple more broadly across the economy.

The dynamic has drawn comparisons to past crises, notably the dot-com bubble. Tech companies also made up a large share of the stock index then — though not as much as today, and many were not nearly as profitable, if they made money at all.

How the current moment compares with past pre-crisis moments

To understand how abnormal and worrisome this moment might be, The New York Times analyzed data from S&P Dow Jones Indices that compiled the market values of the companies in the S&P 500 in December 1999 and August 2007. Each date was chosen roughly three months before a downturn to capture the weighted breakdown of the index before crises fully took hold and values fell.

The companies that make up the index have periodically cycled in and out, and the sectors were reclassified over the last two decades. But even after factoring in those changes, the picture that emerges is a market that is becoming increasingly one-sided.

In December 1999, the tech sector made up 26 percent of the total.

In August 2007, just before the Great Recession, it was only 14 percent.

Today, tech is worth a third of the market, as other vital sectors, such as energy and those that include manufacturing, have shrunk.

Since then, the huge growth of the internet, social media and other technologies propelled the economy.

Now, never has so much of the market been concentrated in so few companies. The top 10 make up almost 40 percent of the S&P 500.

How much of the S&P 500 is occupied by the top 10 companies

With greater concentration of wealth comes greater risk. When so much money has accumulated in just a handful of companies, stock trading can be more volatile and susceptible to large swings. One day after Nvidia posted a huge profit for its most recent quarter, its stock price paradoxically fell by 5.5 percent. So far in 2026, more than a fifth of the stocks in the S&P 500 have moved by 20 percent or more. Companies and industries that are seen as particularly prone to disruption by A.I. have been hard hit.

The volatility can be compounded as everyone reorients their businesses around A.I, or in response to it.

The artificial intelligence boom has touched every corner of the economy. As data centers proliferate to support massive computation, the utilities sector has seen huge growth, fueled by the energy demands of the grid. In 2025, companies like NextEra and Exelon saw their valuations surge.

The industrials sector, too, has undergone a notable shift. General Electric was its undisputed heavyweight in 1999 and 2007, but the recent explosion in data center construction has evened out growth in the sector. GE still leads today, but Caterpillar is a very close second. Caterpillar, which is often associated with construction, has seen a spike in sales of its turbines and power-generation equipment, which are used in data centers.

One large difference between the big tech companies now and their counterparts during the dot-com boom is that many now earn money. A lot of the well-known names in the late 1990s, including Pets.com, had soaring valuations and little revenue, which meant that when the bubble popped, many companies quickly collapsed.

Nvidia, Apple, Alphabet and others generate hundreds of billions of dollars in revenue each year.

And many of the biggest players in artificial intelligence these days are private companies. OpenAI, Anthropic and SpaceX are expected to go public later this year, which could further tilt the market dynamic toward tech and A.I.

Methodology

Sector values reflect the GICS code classification system of companies in the S&P 500. As changes to the GICS system took place from 1999 to now, The New York Times reclassified all companies in the index in 1999 and 2007 with current sector values. All monetary figures from 1999 and 2007 have been adjusted for inflation.

Business

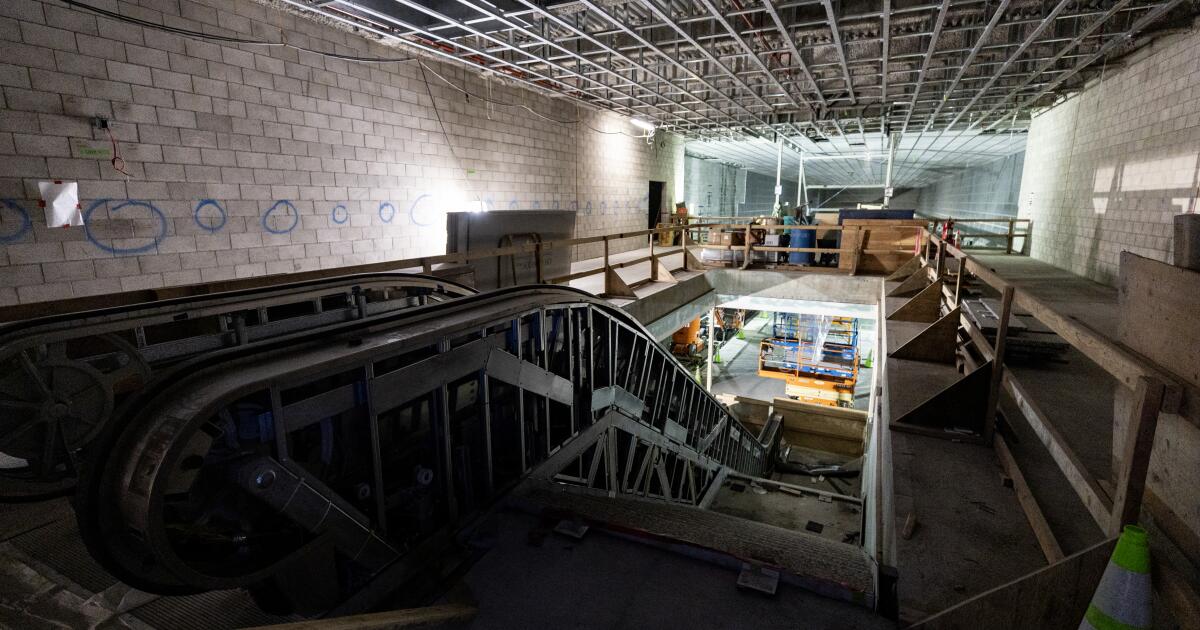

Coming soon: L.A. Metro stops that connect downtown to Beverly Hills, Miracle Mile

Metro has announced it will open three new stations connecting downtown Los Angeles to Beverly Hills in May.

The new stations mark the first phase of a rail extension project on the Metro D line, also known as the Purple Line, beneath Wilshire Boulevard. The extension will open to the public on May 8.

It’s part of a broader plan to enhance the region’s transit infrastructure in time for the 2028 Olympic and Paralympic Games.

The new stations will take riders west, past the existing Wilshire/Western station in Koreatown, and stopping along the Miracle Mile before arriving at Beverly Hills. The 3.92-mile addition winds through Hancock Park, Windsor Square, the Fairfax District and Carthay Circle. The stations will be located at Wilshire/La Brea, Wilshire/Fairfax and Wilshire/La Cienega.

This is the first of three phases in the D Line extension project. The completion of the this phase, budgeted at $3.7 billion, comes months later than earlier projections. Metro said in 2025 it expected to wrap up the phase by the end of the year.

The route between downtown Los Angeles and Koreatown is one of Metro’s most heavily used rail lines, with an average of around 65,000 daily boardings. The Purple Line extension project — with the goal of adding seven stations and expanding service on the line to Hancock Park, Century City, Beverly Hills and Westwood — broke ground more than a decade ago. Metro’s goal is to finish by the 2028 Summer Olympics.

In a news release on Thursday, Metro described its D Line expansion as “one of the highest-priority” transit projects in its portfolio and “a historic milestone.”

“Traveling through Mid-Wilshire to experience the culture, cuisine and commerce across diverse neighborhoods will be easier, faster and more accessible,” said Fernando Dutra, Metro board chair and Whittier City Council member, in the release. “That connectivity from Downtown LA to the westside will serve as a lasting legacy for all Angelenos.”

The D line was closed for more than two months last year for construction under Wilshire Boulevard, contributing to a 13.5% drop in ridership that was exacerbated by immigration raids in the area.

“I can’t wait for everyone to enjoy and discover the vibrance of mid-Wilshire without the traffic,” Metro CEO Stephanie Wiggins said in a statement.

Business

Commentary: AI isn’t ready to be your doctor yet — but will it ever be?

As almost everybody knows, the AI gold rush is upon us. And in few fields is it happening as fast and furiously as in healthcare.

That points to an important corollary: Beware.

Artificial intelligence technology has helped radiologists identify anomalies in images that human users have missed. It has some evident benefits in relieving doctors of the back-office routines that consume hours better spent treating patients, such as filing insurance claims and scheduling appointments.

Eventually, a lot of this stuff is going to be great, but we’re not there yet.

— Eric Topol, Scripps Research

But it has also been accused of providing erroneous information to surgeons during operations that placed their patients at grave risk of injury, and fomenting panic among users who take its offhand responses as serious diagnoses.

The commercial direct-to-consumer applications being promoted by AI firms, such as OpenAI’s ChatGPT Health and Anthropic’s Claude for Healthcare — both of which were introduced in January — raise special concerns among medical professionals. That’s because they’ve been pitched to users who may not appreciate their tendency to output erroneous information errors and offer inappropriate advice.

“Eventually, a lot of this stuff is going to be great, but we’re not there yet,” says Eric Topol, a cardiologist associated with Scripps Research Institute in La Jolla.

“The fact that they’re putting these out without enough anchoring in safety and quality and consistency concerns me,” Topol says. “They need much tighter testing. The problem I have is that these efforts are largely stemming from commercial interests — there’s furious competition to be the first to come out with an app for patients, even if it’s not quite ready yet.”

That was the experience reported by Washington Post technology columnist Geoffrey A. Fowler, who provided ChatGPT with 10 years of health data compiled by his Apple Watch — and received a warning about his cardiac health so dire that it sent him to his cardiologist, who told him he was in the bloom of health.

Fowler also sought out Topol, who reviewed the data and found the Chatbot’s warning to be “baseless.” Anthropic’s chatbot also provided Fowler with a health grade that Topol deemed dubious.

“Claude is designed to help users understand and organize their health information, framing responses as general health information rather than medical advice,” an Anthropic spokesman told me by email. “It can provide clinical context—for example, explaining how a lab value compares to diagnostic thresholds—while clearly stating that formal diagnosis requires professional evaluation.”

OpenAI didn’t respond to my questions about the safety and reliability of its consumer app.

Topol, who has written extensively about advanced technology in medicine, is nothing like an AI skeptic. He calls himself an AI optimist, citing numerous studies showing that artificial intelligence can help doctors treat patients more effectively and even to improve their bedside manners.

But he cautions that “healthcare can’t tolerate significant errors. We have to minimize the errors, the hallucinations, the confabulations, the BS and the sycophancy” that AI technology commonly displays.

In medicine, as in many other fields, AI looks to have been oversold as a labor-saving technology. According to a study of AI-equipped stethoscopes provided to about 100 British medical groups published earlier this month in the Lancet, the British medical journal, the high-tech stethoscopes effectively identified some (but not all) indications of heart failure better than conventional stethoscopes. But 40% of the groups abandoned the new devices during the 12-month period of the study.

The main complaint was the “additional workflow burden” experienced by the users — an indication that whatever the virtues of the new technology, they didn’t outweigh the time and effort needed to use them.

Other studies have found that AI can augment physicians’ skills — when the doctors have learned to trust their AI tools and when they’re used in relatively uncomplicated, even generic, conditions.

The most notable benefits have been found in radiology; according to a Dutch study published last year, radiologists using AI to help interpret breast X-rays did as well in finding cancers as two radiologists working together. That suggested that judicious use of AI could free up time for one of the two radiologists. But in this case as in others, the AI helper didn’t do consistently well.

“AI misses some breast cancers that are recalled by human assessment,” a study author said, “but detects a similar number of breast cancers otherwise missed by the interpreting radiologists.”

AI’s incursion into healthcare even has become something of a cultural touchstone: In HBO’s up-to-the-minute emergency room series “The Pitt,” beleaguered ER doctors discover that an AI app pushed on them as a time-saving charting tool has “hallucinated” a history of appendicitis for a patient, endangering the patient’s treatment.

“Generative AI is not perfect,” the app’s sponsor responds. “We still need to proofread every chart it creates” — thus acknowledging, accurately, that AI can increase, not relieve, users’ workloads.

A future in which robots perform surgical operations or make accurate diagnoses remains the stuff of science fiction. In medicine, as elsewhere, AI technology has been shown to be useful to take over automatable tasks from humans, but not in situations requiring human ingenuity or creativity — or precision. And attempts to use AI-related algorithms to make healthcare judgments have been challenged in court.

In a class-action lawsuit filed in Minnesota federal court in 2023, five Medicare patients and survivors of three others allege that UnitedHealth Group, the nation’s largest medical insurer, relied on an AI algorithm to deny coverage for their care, “overriding their treating physicians’ determinations as to medically necessary care based on an AI model” with a 90% error rate.

The case is pending. In its defense, UnitedHealth has asserted that decisions on whether to approve or deny coverage remain entirely in the hands of physicians and other clinical professionals the company employs, and their decisions on coverage and care comply with Medicare standards.

The AI algorithm cited by the plaintiffs, UnitedHealth says, is not used “to deny care to members or to make adverse medical necessity coverage determinations,” but rather to help physicians and patients “anticipate and plan for future care needs.” The company didn’t address the plaintiffs’ assertion about the algorithm’s error rate.

“We shouldn’t be complacent about accepting errors” from AI tools, Topol told me. But it’s proper to wonder whether that message has been absorbed by promoters of AI health applications.

Disclaimers warning that AI responses “are not professionally vetted or a substitute for medical advice” have all but disappeared from AI platforms, according to a survey by researchers at Stanford and UC Berkeley.

The issue becomes more urgent as the language of chatbots becomes more sophisticated and fluent, inspiring unwarranted confidence in their conclusions, the researchers cautioned. “Users may misinterpret AI-generated content as expert guidance,” they wrote, “potentially resulting in delayed treatment, inappropriate self-care, or misplaced trust in non-validated information.”

Typically, state laws require that medical diagnoses and clinical decisions proceed from physical examinations by licensed doctors and after a full workup of a patient’s medical and family history. They don’t necessarily rule out doctors’ use of AI to help them develop diagnoses or treatment plans, but the doctors must remain in control.

The Food and Drug Administration exempts medical devices from government licensing if they’re “intended generally for patient education, and … not intended for use in the diagnosis of disease or other conditions. That may cover AI bots if they’re not issuing diagnoses.

But that may not help users who have willingly uploaded their medical histories and test results to AI bots, unaware of concerns, including whether their information will be kept private or used against them in insurance decisions. Gaps in their uploaded data my affect the advice they receive from bots. And because the bots know nothing except the content they’ve been fed, their healthcare outputs may reflect cultural biases in the basic data, such as ethnic disparities in disease incidence and treatment.

“If there’s a mistake with all your data, you could get into a pretty severe anxiety attack,” Topol says. “Patients should verify, not just trust” what they’ve heard from a bot.

Topol warns that the negative effect of misleading AI information may not only fall on patients, but on the AI field itself. “The public doesn’t really differentiate between individual bots,” he told me. “All we need are some horror stories” about misdiagnoses or dangerous advice, “and that whole area is tarred.”

In his view, that would limit the promise of technologies that could improve the effectiveness of medical practice in many ways. The remedy is for AI applications to be subjected to the same clinical standards applied to “a drug, a device, a diagnostic. We can’t lower the threshold because it’s something new, or different, with some broad appeal.”

-

World1 day ago

World1 day agoExclusive: DeepSeek withholds latest AI model from US chipmakers including Nvidia, sources say

-

Massachusetts2 days ago

Massachusetts2 days agoMother and daughter injured in Taunton house explosion

-

Montana1 week ago

Montana1 week ago2026 MHSA Montana Wrestling State Championship Brackets And Results – FloWrestling

-

Oklahoma1 week ago

Oklahoma1 week agoWildfires rage in Oklahoma as thousands urged to evacuate a small city

-

Louisiana4 days ago

Louisiana4 days agoWildfire near Gum Swamp Road in Livingston Parish now under control; more than 200 acres burned

-

Technology6 days ago

Technology6 days agoYouTube TV billing scam emails are hitting inboxes

-

Denver, CO2 days ago

Denver, CO2 days ago10 acres charred, 5 injured in Thornton grass fire, evacuation orders lifted

-

Technology6 days ago

Technology6 days agoStellantis is in a crisis of its own making