Business

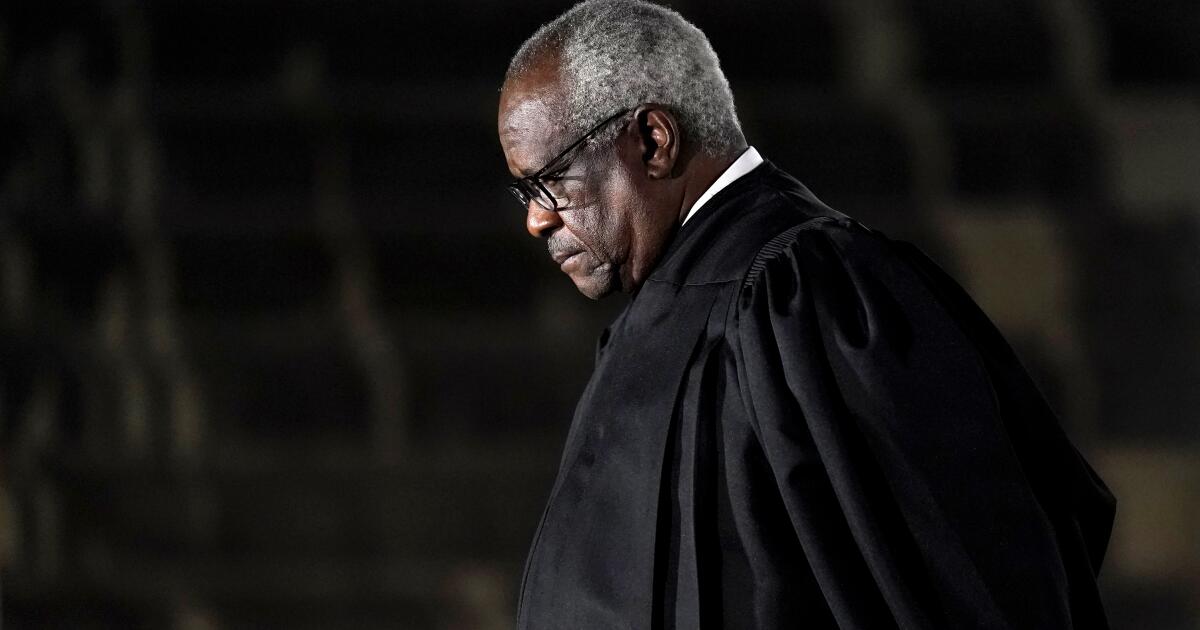

Column: Clarence Thomas and the bottomless self-pity of the upper classes

Articles asking us to feel sympathy for families barely scraping by on healthy six-figure incomes may be staples of the financial press, but it’s rare that they come packaged as real-world case studies attached to flesh-and-blood individuals.

But that’s what happened just before Christmas, when law professor Steven Calabresi defended Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas’ shadowy financial relationships with a passel of conservative billionaires by explaining that Thomas simply was trying to avoid the difficulty of surviving on his government salary of $285,400 a year.

“If Congress had adjusted for inflation the salary that Supreme Court justices made in 1969 at the end of the Warren Court, Justice Thomas would be being paid $500,000 a year,” Calabresi wrote, “and he would not need to rely as much as he has on gifts from wealthy friends.”

That’s a novel definition of “neediness”: Calabresi was saying that Thomas had no choice but to create an ethical quandary for himself by accepting gifts from “friends,” some of whom have interests directly or indirectly connected with cases before the Supreme Court and on which Thomas has ruled.

If Congress had adjusted for inflation the salary that Supreme Court justices made in 1969…, Justice Thomas would be being paid $500,000 a year, and he would not need to rely as much as he has on gifts from wealthy friends.

— Steven Calabresi, Reason Magazine

Given these ethical issues, Calabresi’s argument attracted some sarcasm. University of Colorado law professor Paul Campos interpreted its gist as: “It’s just fundamentally unreasonable to expect a SCOTUS justice to scrape along on nearly $300K per year in salary, without expecting that he’ll accept a petit cadeau or thirty, from billionaires who just can’t stand the sight of so much human suffering.”

Still, it’s useful to view the argument in the context of our never-ending debate about income and wealth in America. The debate regularly generates articles purporting to explain how outwardly wealthy families can’t make ends meet on income even as high as $500,000.

There was a noticeable surge in the genre in late 2020, when then-presidential candidate Joe Biden said he would guarantee no tax increases for households collecting less than $400,000. His definition of that income as the threshold of “wealthy” elicited instant pushback from writers arguing that it was no such thing.

As I’ve pointed out before, accounts of the penuriousness of life on such an income invariably involve financial legerdemain. The expense budgets published with these articles generally place the subject households in the costliest neighborhoods in the country, such as in San Francisco or Manhattan.

They also describe as necessary or unavoidable expenses many items that most ordinary families would consider luxuries. An article tied to Biden’s $400,000 promise, for instance, showed how its hypothetical family with that much income ended the year with only $34 on hand to cover “miscellaneous” expenses.

Along the way, however, the emblematic couple (two lawyers with two kids) paid $39,000 into their 401(k) retirement plans, $18,000 into 529 savings plans for college, and more than $100,000 on the mortgage and property taxes on their $2-million home. Also, food with “regular food delivery,” life insurance, weekend getaways, clothes and personal care products.

Calabresi’s hand-wringing on Thomas’ behalf also engages in sleight of hand. He doesn’t mention that Thomas’ wife, Ginni, has her own career as a lawyer and consultant, though her income is unknown. (Thomas listed her employment on his most recent financial disclosure statement, but not her salary and benefits.)

Nor does Calabresi acknowledge that much of the gifting from wealthy friends on which Thomas purportedly “needs to rely” has had nothing to do with meeting the rigors of daily life as the average person would imagine them.

As ProPublica reported, they included “at least 38 destination vacations, including a previously unreported voyage on a yacht around the Bahamas; 26 private jet flights, plus an additional eight by helicopter; a dozen VIP passes to professional and college sporting events, typically perched in the skybox; two stays at luxury resorts in Florida and Jamaica; and one standing invitation to an uber-exclusive golf club overlooking the Atlantic coast.”

To Calabresi, the questioning of this largess by the “left wing” is “sickening and unfair,” since in his view Thomas is “the best and most incorruptible Supreme Court justice in U.S. history.” Your mileage may vary; the overall tone of Calabresi’s piece is reminiscent of the line, “Raymond Shaw is the kindest, bravest, warmest, most wonderful human being I’ve ever known in my life,” uttered repeatedly in the movie “The Manchurian Candidate.”

It’s worth noting that in the movie, the line is spoken by soldiers who were brainwashed at a North Korean prison camp. Just saying.

Calabresi benchmarked Thomas’ salary against those of law school deans or young lawyers with sterling credentials such as former Supreme Court clerks, which he placed at about $500,000 a year. But discussions turning on the relative pay of various jobs and professions always have an otherworldly, even absurd, feel.

In part that’s because it’s harder than you might think to compare the work of a Supreme Court justice to that of a law school dean — not to mention comparing the work of a justice to that of a merchandise picker in an Amazon warehouse.

As Campos observes, Supreme Court justices have lifetime sinecures (only one has ever been removed through impeachment), a lifetime pension at full pay after retirement, a huge professional bureaucracy to lean on, an annual three-month paid vacation and the “psychic benefit” of being endlessly praised for their perspicacity, wisdom and (to cite Calabresi) incorruptibility. Law school deans and lawyers can’t match those bennies.

For further perspective, the federal minimum wage has been frozen at $7.25 an hour since July 2009. In that time span, its purchasing power has fallen to $5.08. In the same period, the salary of Supreme Court justices has risen to $285,400 from $213,900, an increase of 33.4%.

That may not have quite kept up with inflation, which would have raised the justices’ pay to about $311,060 since 2009, but it’s not anything like the march backward experienced by those on the federal minimum wage.

It’s true that representatives and senators also haven’t received a pay raise since 2009, but they’re not exactly living on the minimum wage: The salaries for rank-and-file legislators is $174,000 but the majority and minority leaders of both chambers and the Senate president pro tem get $193,400 and the House speaker gets $223,500.

They also pay into and receive Social Security, have a separate pension benefit and have access to government health insurance. Anyway, they collect more than twice the median household income in America, which is about $75,000.

Occasionally some journalist will make the argument that Congress should be paid more. I’ve done it twice, in 2013 and 2019, on the argument that it might attract more candidates devoted to making government work.

But those were in the halcyon days before Capitol Hill was only partly, not entirely, dysfunctional. I wouldn’t make the same argument today, when there’s reason to doubt that a higher wage would attract anyone better than the buffoons who walk the hallways of the House of Representatives at the moment.

Indeed, a higher wage might increase the psychological distance between our elected representatives and their constituents.

Just compare how eager they were in December 2017 to enact a huge tax cut for the wealthy, which passed a GOP-controlled Congress on the nod and was promptly signed by President Trump, with the dithering over the child tax credit, an immensely successful anti-poverty program that they allowed to expire at the beginning of 2022 and is just now back on the negotiating table, with no guarantee of restoration.

That tells you that the gulf between the lawmakers and the people they supposedly represent is already too wide.

As for the other argument, that paying them and the Supreme Court justices more would reduce their incentive to take bribes, just what sort of people are we electing and appointing to office?

How much more would we have to pay Clarence Thomas to get him to stop taking free yacht voyages and private flights to private clubs from rich “friends”? Sadly, to ask the question is to answer it.

Business

How the S&P 500 Stock Index Became So Skewed to Tech and A.I.

Nvidia, the chipmaker that became the world’s most valuable public company two years ago, was alone worth more than $4.75 trillion as of Thursday morning. Its value, or market capitalization, is more than double the combined worth of all the companies in the energy sector, including oil giants like Exxon Mobil and Chevron.

The chipmaker’s market cap has swelled so much recently, it is now 20 percent greater than the sum of all of the companies in the materials, utilities and real estate sectors combined.

What unifies these giant tech companies is artificial intelligence. Nvidia makes the hardware that powers it; Microsoft, Apple and others have been making big bets on products that people can use in their everyday lives.

But as worries grow over lavish spending on A.I., as well as the technology’s potential to disrupt large swaths of the economy, the outsize influence that these companies exert over markets has raised alarms. They can mask underlying risks in other parts of the index. And if a handful of these giants falter, it could mean widespread damage to investors’ portfolios and retirement funds in ways that could ripple more broadly across the economy.

The dynamic has drawn comparisons to past crises, notably the dot-com bubble. Tech companies also made up a large share of the stock index then — though not as much as today, and many were not nearly as profitable, if they made money at all.

How the current moment compares with past pre-crisis moments

To understand how abnormal and worrisome this moment might be, The New York Times analyzed data from S&P Dow Jones Indices that compiled the market values of the companies in the S&P 500 in December 1999 and August 2007. Each date was chosen roughly three months before a downturn to capture the weighted breakdown of the index before crises fully took hold and values fell.

The companies that make up the index have periodically cycled in and out, and the sectors were reclassified over the last two decades. But even after factoring in those changes, the picture that emerges is a market that is becoming increasingly one-sided.

In December 1999, the tech sector made up 26 percent of the total.

In August 2007, just before the Great Recession, it was only 14 percent.

Today, tech is worth a third of the market, as other vital sectors, such as energy and those that include manufacturing, have shrunk.

Since then, the huge growth of the internet, social media and other technologies propelled the economy.

Now, never has so much of the market been concentrated in so few companies. The top 10 make up almost 40 percent of the S&P 500.

How much of the S&P 500 is occupied by the top 10 companies

With greater concentration of wealth comes greater risk. When so much money has accumulated in just a handful of companies, stock trading can be more volatile and susceptible to large swings. One day after Nvidia posted a huge profit for its most recent quarter, its stock price paradoxically fell by 5.5 percent. So far in 2026, more than a fifth of the stocks in the S&P 500 have moved by 20 percent or more. Companies and industries that are seen as particularly prone to disruption by A.I. have been hard hit.

The volatility can be compounded as everyone reorients their businesses around A.I, or in response to it.

The artificial intelligence boom has touched every corner of the economy. As data centers proliferate to support massive computation, the utilities sector has seen huge growth, fueled by the energy demands of the grid. In 2025, companies like NextEra and Exelon saw their valuations surge.

The industrials sector, too, has undergone a notable shift. General Electric was its undisputed heavyweight in 1999 and 2007, but the recent explosion in data center construction has evened out growth in the sector. GE still leads today, but Caterpillar is a very close second. Caterpillar, which is often associated with construction, has seen a spike in sales of its turbines and power-generation equipment, which are used in data centers.

One large difference between the big tech companies now and their counterparts during the dot-com boom is that many now earn money. A lot of the well-known names in the late 1990s, including Pets.com, had soaring valuations and little revenue, which meant that when the bubble popped, many companies quickly collapsed.

Nvidia, Apple, Alphabet and others generate hundreds of billions of dollars in revenue each year.

And many of the biggest players in artificial intelligence these days are private companies. OpenAI, Anthropic and SpaceX are expected to go public later this year, which could further tilt the market dynamic toward tech and A.I.

Methodology

Sector values reflect the GICS code classification system of companies in the S&P 500. As changes to the GICS system took place from 1999 to now, The New York Times reclassified all companies in the index in 1999 and 2007 with current sector values. All monetary figures from 1999 and 2007 have been adjusted for inflation.

Business

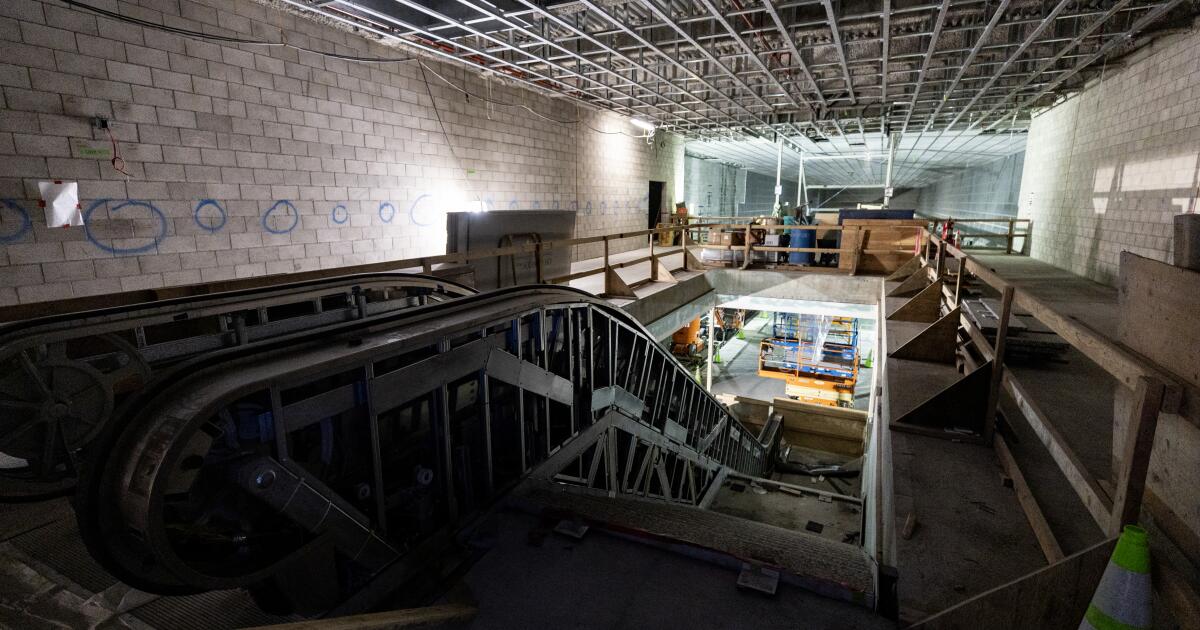

Coming soon: L.A. Metro stops that connect downtown to Beverly Hills, Miracle Mile

Metro has announced it will open three new stations connecting downtown Los Angeles to Beverly Hills in May.

The new stations mark the first phase of a rail extension project on the Metro D line, also known as the Purple Line, beneath Wilshire Boulevard. The extension will open to the public on May 8.

It’s part of a broader plan to enhance the region’s transit infrastructure in time for the 2028 Olympic and Paralympic Games.

The new stations will take riders west, past the existing Wilshire/Western station in Koreatown, and stopping along the Miracle Mile before arriving at Beverly Hills. The 3.92-mile addition winds through Hancock Park, Windsor Square, the Fairfax District and Carthay Circle. The stations will be located at Wilshire/La Brea, Wilshire/Fairfax and Wilshire/La Cienega.

This is the first of three phases in the D Line extension project. The completion of the this phase, budgeted at $3.7 billion, comes months later than earlier projections. Metro said in 2025 it expected to wrap up the phase by the end of the year.

The route between downtown Los Angeles and Koreatown is one of Metro’s most heavily used rail lines, with an average of around 65,000 daily boardings. The Purple Line extension project — with the goal of adding seven stations and expanding service on the line to Hancock Park, Century City, Beverly Hills and Westwood — broke ground more than a decade ago. Metro’s goal is to finish by the 2028 Summer Olympics.

In a news release on Thursday, Metro described its D Line expansion as “one of the highest-priority” transit projects in its portfolio and “a historic milestone.”

“Traveling through Mid-Wilshire to experience the culture, cuisine and commerce across diverse neighborhoods will be easier, faster and more accessible,” said Fernando Dutra, Metro board chair and Whittier City Council member, in the release. “That connectivity from Downtown LA to the westside will serve as a lasting legacy for all Angelenos.”

The D line was closed for more than two months last year for construction under Wilshire Boulevard, contributing to a 13.5% drop in ridership that was exacerbated by immigration raids in the area.

“I can’t wait for everyone to enjoy and discover the vibrance of mid-Wilshire without the traffic,” Metro CEO Stephanie Wiggins said in a statement.

Business

Commentary: AI isn’t ready to be your doctor yet — but will it ever be?

As almost everybody knows, the AI gold rush is upon us. And in few fields is it happening as fast and furiously as in healthcare.

That points to an important corollary: Beware.

Artificial intelligence technology has helped radiologists identify anomalies in images that human users have missed. It has some evident benefits in relieving doctors of the back-office routines that consume hours better spent treating patients, such as filing insurance claims and scheduling appointments.

Eventually, a lot of this stuff is going to be great, but we’re not there yet.

— Eric Topol, Scripps Research

But it has also been accused of providing erroneous information to surgeons during operations that placed their patients at grave risk of injury, and fomenting panic among users who take its offhand responses as serious diagnoses.

The commercial direct-to-consumer applications being promoted by AI firms, such as OpenAI’s ChatGPT Health and Anthropic’s Claude for Healthcare — both of which were introduced in January — raise special concerns among medical professionals. That’s because they’ve been pitched to users who may not appreciate their tendency to output erroneous information errors and offer inappropriate advice.

“Eventually, a lot of this stuff is going to be great, but we’re not there yet,” says Eric Topol, a cardiologist associated with Scripps Research Institute in La Jolla.

“The fact that they’re putting these out without enough anchoring in safety and quality and consistency concerns me,” Topol says. “They need much tighter testing. The problem I have is that these efforts are largely stemming from commercial interests — there’s furious competition to be the first to come out with an app for patients, even if it’s not quite ready yet.”

That was the experience reported by Washington Post technology columnist Geoffrey A. Fowler, who provided ChatGPT with 10 years of health data compiled by his Apple Watch — and received a warning about his cardiac health so dire that it sent him to his cardiologist, who told him he was in the bloom of health.

Fowler also sought out Topol, who reviewed the data and found the Chatbot’s warning to be “baseless.” Anthropic’s chatbot also provided Fowler with a health grade that Topol deemed dubious.

“Claude is designed to help users understand and organize their health information, framing responses as general health information rather than medical advice,” an Anthropic spokesman told me by email. “It can provide clinical context—for example, explaining how a lab value compares to diagnostic thresholds—while clearly stating that formal diagnosis requires professional evaluation.”

OpenAI didn’t respond to my questions about the safety and reliability of its consumer app.

Topol, who has written extensively about advanced technology in medicine, is nothing like an AI skeptic. He calls himself an AI optimist, citing numerous studies showing that artificial intelligence can help doctors treat patients more effectively and even to improve their bedside manners.

But he cautions that “healthcare can’t tolerate significant errors. We have to minimize the errors, the hallucinations, the confabulations, the BS and the sycophancy” that AI technology commonly displays.

In medicine, as in many other fields, AI looks to have been oversold as a labor-saving technology. According to a study of AI-equipped stethoscopes provided to about 100 British medical groups published earlier this month in the Lancet, the British medical journal, the high-tech stethoscopes effectively identified some (but not all) indications of heart failure better than conventional stethoscopes. But 40% of the groups abandoned the new devices during the 12-month period of the study.

The main complaint was the “additional workflow burden” experienced by the users — an indication that whatever the virtues of the new technology, they didn’t outweigh the time and effort needed to use them.

Other studies have found that AI can augment physicians’ skills — when the doctors have learned to trust their AI tools and when they’re used in relatively uncomplicated, even generic, conditions.

The most notable benefits have been found in radiology; according to a Dutch study published last year, radiologists using AI to help interpret breast X-rays did as well in finding cancers as two radiologists working together. That suggested that judicious use of AI could free up time for one of the two radiologists. But in this case as in others, the AI helper didn’t do consistently well.

“AI misses some breast cancers that are recalled by human assessment,” a study author said, “but detects a similar number of breast cancers otherwise missed by the interpreting radiologists.”

AI’s incursion into healthcare even has become something of a cultural touchstone: In HBO’s up-to-the-minute emergency room series “The Pitt,” beleaguered ER doctors discover that an AI app pushed on them as a time-saving charting tool has “hallucinated” a history of appendicitis for a patient, endangering the patient’s treatment.

“Generative AI is not perfect,” the app’s sponsor responds. “We still need to proofread every chart it creates” — thus acknowledging, accurately, that AI can increase, not relieve, users’ workloads.

A future in which robots perform surgical operations or make accurate diagnoses remains the stuff of science fiction. In medicine, as elsewhere, AI technology has been shown to be useful to take over automatable tasks from humans, but not in situations requiring human ingenuity or creativity — or precision. And attempts to use AI-related algorithms to make healthcare judgments have been challenged in court.

In a class-action lawsuit filed in Minnesota federal court in 2023, five Medicare patients and survivors of three others allege that UnitedHealth Group, the nation’s largest medical insurer, relied on an AI algorithm to deny coverage for their care, “overriding their treating physicians’ determinations as to medically necessary care based on an AI model” with a 90% error rate.

The case is pending. In its defense, UnitedHealth has asserted that decisions on whether to approve or deny coverage remain entirely in the hands of physicians and other clinical professionals the company employs, and their decisions on coverage and care comply with Medicare standards.

The AI algorithm cited by the plaintiffs, UnitedHealth says, is not used “to deny care to members or to make adverse medical necessity coverage determinations,” but rather to help physicians and patients “anticipate and plan for future care needs.” The company didn’t address the plaintiffs’ assertion about the algorithm’s error rate.

“We shouldn’t be complacent about accepting errors” from AI tools, Topol told me. But it’s proper to wonder whether that message has been absorbed by promoters of AI health applications.

Disclaimers warning that AI responses “are not professionally vetted or a substitute for medical advice” have all but disappeared from AI platforms, according to a survey by researchers at Stanford and UC Berkeley.

The issue becomes more urgent as the language of chatbots becomes more sophisticated and fluent, inspiring unwarranted confidence in their conclusions, the researchers cautioned. “Users may misinterpret AI-generated content as expert guidance,” they wrote, “potentially resulting in delayed treatment, inappropriate self-care, or misplaced trust in non-validated information.”

Typically, state laws require that medical diagnoses and clinical decisions proceed from physical examinations by licensed doctors and after a full workup of a patient’s medical and family history. They don’t necessarily rule out doctors’ use of AI to help them develop diagnoses or treatment plans, but the doctors must remain in control.

The Food and Drug Administration exempts medical devices from government licensing if they’re “intended generally for patient education, and … not intended for use in the diagnosis of disease or other conditions. That may cover AI bots if they’re not issuing diagnoses.

But that may not help users who have willingly uploaded their medical histories and test results to AI bots, unaware of concerns, including whether their information will be kept private or used against them in insurance decisions. Gaps in their uploaded data my affect the advice they receive from bots. And because the bots know nothing except the content they’ve been fed, their healthcare outputs may reflect cultural biases in the basic data, such as ethnic disparities in disease incidence and treatment.

“If there’s a mistake with all your data, you could get into a pretty severe anxiety attack,” Topol says. “Patients should verify, not just trust” what they’ve heard from a bot.

Topol warns that the negative effect of misleading AI information may not only fall on patients, but on the AI field itself. “The public doesn’t really differentiate between individual bots,” he told me. “All we need are some horror stories” about misdiagnoses or dangerous advice, “and that whole area is tarred.”

In his view, that would limit the promise of technologies that could improve the effectiveness of medical practice in many ways. The remedy is for AI applications to be subjected to the same clinical standards applied to “a drug, a device, a diagnostic. We can’t lower the threshold because it’s something new, or different, with some broad appeal.”

-

World1 day ago

World1 day agoExclusive: DeepSeek withholds latest AI model from US chipmakers including Nvidia, sources say

-

Massachusetts2 days ago

Massachusetts2 days agoMother and daughter injured in Taunton house explosion

-

Montana1 week ago

Montana1 week ago2026 MHSA Montana Wrestling State Championship Brackets And Results – FloWrestling

-

Oklahoma1 week ago

Oklahoma1 week agoWildfires rage in Oklahoma as thousands urged to evacuate a small city

-

Louisiana4 days ago

Louisiana4 days agoWildfire near Gum Swamp Road in Livingston Parish now under control; more than 200 acres burned

-

Technology6 days ago

Technology6 days agoYouTube TV billing scam emails are hitting inboxes

-

Denver, CO2 days ago

Denver, CO2 days ago10 acres charred, 5 injured in Thornton grass fire, evacuation orders lifted

-

Technology6 days ago

Technology6 days agoStellantis is in a crisis of its own making