Business

Column: Businesses keep complaining about shoplifting, but wage theft is a bigger crime

Former Home Depot Chief Executive Bob Nardelli went on Fox Business the other day to warn that a surge in shoplifting by organized gangs showed that America was descending into “a lawless society.”

“We’ve got to get this back under control,” Nardelli intoned gloomily, after videos of smash-and-grab teams in retail stores had spooled behind him. “I fear where this is headed.”

There isn’t much to say about Nardelli’s sepulchral comments, other than that he has a hell of a nerve.

Selective reporting of retail theft incidents by retailers and skewed media coverage of retail theft (has) tended to focus on sensational incidents that feature violence or brazen daytime theft operations.

— National Retail Federation tells the truth about the shoplifting crisis

Back in June, Nardelli’s former company settled a class-action lawsuit with workers alleging widespread wage theft for $72.5 million.

More than 885,000 Home Depot workers were members of the various classes, including those who were locked in their stores off-the-clock following the day’s closing shift until a supervisor got around to letting them out. Home Depot didn’t admit to the allegations, and said it had settled merely to make the lawsuit go away.

Juxtaposing Nardelli’s remarks and the settlement points to the discordance in how we define “crime” in the workplace. On the one hand, sporadic robberies inflated by retail lobbyists and media via eye-catching reports; on the other, the pervasive shortchanging of hourly workers by their employers.

Estimates of the scale of both phenomena are all over the map, but run into billions of dollars a year. Yet it’s reasonable to conclude that, in terms of the direct impact on households, wage theft is the bigger deal.

Let’s take a look, starting with what retailers call “shrink.”

The term covers three categories of loss: First is “external theft,” such as individual shoplifting and organized retail crime exemplified by those mass invasions of shops by gangs. Then there’s internal theft — pilferage or embezzlement by employees. Finally, what retailers call process and control failures, such as paperwork glitches and other mixups that result in their losing track of inventory.

It’s the first category that gets all the attention, thanks to those video reports so popular on cable and local news shows, and to corporate executives trying to blame their inventory shortfalls on outside parties beyond their control, rather than breakdowns in their internal systems.

A survey published last year by the National Retail Federation attributed 37% of all “shrink” to external theft, but more than 54% to those two internal categories.

Yet executives talk as though external theft is the whole ballgame. They lobby local, state and federal law enforcement agencies to pump up their efforts against it — and largely succeed.

As it happened, an independent study commissioned by the NRF itself acknowledged that the public’s perception of the scale of organized retail theft has been distorted by “selective reporting of retail theft incidents by retailers and skewed media coverage of retail theft,” which has “tended to focus on sensational incidents that feature violence or brazen daytime theft operations.”

The panic inspired by these reports has gone on for years, as my colleague Sam Dean documented in 2021. Dean showed that retail groups’ estimate of $70 billion lost annually to organized thieves was conjured out of thin air. The NRF last year raised its estimate to $94.5 billion for 2021.

That feeds the claim commonly heard these days that the level of organized theft has reached “unprecedented levels” (to quote a recent report by ABC News). But it’s based on very misleading math.

As a percentage of total retail sales, “shrink” has barely budged. The NRF estimated it at 1.4% of retail sales in fiscal 2021, the latest year available. That’s exactly what it was in fiscal 2016. The percentage edged up to 1.6% in fiscal 2019 and 2020 before falling back down.

Total retail sales, however, have risen inexorably, according to the Census Bureau, from about $6.2 trillion in 2019 to $7.4 trillion in 2021 and $8.1 trillion in 2022. That means that retail theft will continue to reach “unprecedented” levels in absolute terms even if its percentage of total sales doesn’t change.

It’s not unusual for corporate leaders to play games with these figures to distract investors. Dick’s Sporting Goods, which is often cited as a victim of organized theft rings, said its gross profit for the second quarter of this year that ended July 30 fell “in large part to the impact of elevated inventory shrink, an increasingly serious issue impacting many retailers,” as CEO Lauren Hobart put it.

The company’s quarterly earnings report, however, explained that only about one-third of the decrease in its quarterly profit margin was due to “inventory shrink.” Most of the rest was due to larger discounts on merchandise — another issue “impacting many retailers” that had saddled themselves with excess inventory after misjudging consumer demand.

Another factor in the elevation of retail theft into an all-consuming “crisis” is partisanship. Nardelli’s comments are a perfect example. He used his Fox Business appearance to blame the problem on — no surprise here, given the forum — President Biden.

“We have a crushing inflation and a crippling interest rate in this economic environment that this administration has put us under,” he said.

Nardelli, who is also a former CEO of Chrysler, also groused about unions seeking higher pay, in case you were wondering where he’s coming from.

Nardelli was especially exercised by the recent contract settlement between United Parcel Service and the Teamsters, which he said was going to “inflate inflation…. When wages are going up, package costs will go up.” He mentioned a contract provision requiring UPS to equip its trucks with air-conditioning. “That’s going to be another increase because of fuel costs,” he said.

Better, in the Nardelli and Fox world, to have drivers broiling to death in their trucks to keep your delivery costs low.

That brings us to the other side of the coin on workplace crime, wage theft. That’s been estimated as high as $50 billion a year by the Economic Policy Institute, which extrapolated from a 2008 survey of low-wage front-line workers in Los Angeles, Chicago and New York.

Employers use a multitude of methods to steal wages. They may pay workers less than the legal minimum wage, fail to pay overtime, deny workers legal meal breaks or rest periods, divert workers’ tips, or require them to work off-the-clock to prepare for their shifts or to perform duties after their shifts have ended.

A glaring new technique is the misclassification of workers as “independent contractors” rather than employees, thus sticking the workers with expenses that would be covered for employees. Uber, Lyft and other gig companies have perfected this practice and made it the bedrock of their business model. But it’s properly regarded as wage theft.

In 2019, when the gig companies drafted Proposition 22 to overturn a California law mandating that their drivers and delivery workers be treated as employees, they claimed that it would guarantee an hourly pay scale of 120% of the state’s minimum wage.

That came to $15.60 an hour in 2019, based on the state minimum wage of $13, and $18.60 this year, when the minimum wage is $15.50.

As Ken Jacobs and Michael Reich of the UC Berkeley Labor Center determined, however, the loopholes written into the measure — exemptions for driver waiting time, underpayments for gas, vehicle wear and tear and insurance, and the cost of Social Security and Medicare taxes — reduced the actual hourly compensation for Uber and Lyft drivers to an average of $5.64 an hour.

The flash mob shoplifting sprees obviously are concentrated in the retail sector, but wage theft can be perpetrated by any business, large or small.

It’s not uncommon for accusations to be laid against franchise businesses. But Amazon, which operates only a handful of retail stores, last year settled wage-theft allegations by warehouse workers in Oregon for $18 million and paid $61.7 million in 2021 to settle a Federal Trade Commission accusation that it stiffed gig-based delivery drivers.

The FTC alleged that Amazon cut the hourly pay originally promised the drivers without giving them adequate notice and diverted tips that customers paid, which the company had said would flow 100% to the drivers. The $61.7 million was “the full amount that Amazon allegedly withheld from drivers,” the FTC said. After the FTC opened its investigation, Amazon restored the original pay scale.

Other big companies that have settled wage-theft claims including Walmart, which led the roster of settlements with $1.4 billion in payments from 2000 to 2018, followed by FedEx, at more than $500 million, according to the advocacy organization Good Jobs First.

Other legal settlements involved companies not commonly thought of as employers of low-income workers, such as Bank of America ($382 million in 2000-18 penalties according to the Good Jobs First survey), Wells Fargo ($205.4 million) and JPMorgan Chase ($160.5 million). These firms’ marquee workers tend to be well-paid professionals, but they’re supported by legions of back-office clerks and other workers paid by the hour.

Billions of dollars a year are returned to cheated workers, but it’s at best a smidgen of what they’ve lost. Wage theft is a flagrant violation of the federal Fair Labor Standards Act, but enforcement has been systematically hampered by the business lobby in Congress.

Indeed, the aggressive actions by former Labor Department official David Weil to protect the wages of working people from thievery that led last year to the Senate rejection of his nomination by Biden to return to the agency’s Wage and Hour Division.

As I wrote after Weil was forced to withdraw his name from consideration, he had come under ferocious attack by business interests and Republicans from the start, because they knew of his commitment to enforcing the labor laws on the books and the court rulings that have upheld them.

The division’s budget had been “flatlined for more than a decade,” Weil told me then, not even counting the impact of inflation.

Measuring the Wage and Hour Division’s workforce in the past against its payroll today and considering the vastly greater number of workers and workplaces within its jurisdiction, Weil estimated that the division in 1940 had 64 times the capacity that it has now to investigate violations.

Compare that with the enthusiasm that officials in Washington and state governments muster to fight flash-mob robberies with more police, focused investigations and tighter laws. If you’re a big business, your exaggerated complaints get heard at the highest levels. If you’re a working man or woman being nickel-and-dimed by unscrupulous employers, you’re on your own.

Business

Biden Administration Adopts Rules to Guide A.I.’s Global Spread

The Biden administration issued sweeping rules on Monday governing how A.I. chips and models can be shared with foreign countries, in an attempt to set up a global framework that will guide how artificial intelligence spreads around the world in the years to come.

With the power of A.I. rapidly growing, the Biden administration said the rules were necessary to keep a transformational technology under the control of the United States and its allies, and out of the hands of adversaries that could use it to augment their militaries, carry out cyberattacks and otherwise threaten the United States.

Tech companies have protested the new rules, saying they threaten their sales and the future prospects of the American tech industry.

The rules put various limitations on the number of A.I. chips that companies can send to different countries, essentially dividing the world into three categories. The United States and 18 of its closest partners — including Britain, Canada, Germany, Japan, South Korea and Taiwan — are exempted from any restrictions and can buy A.I. chips freely.

Countries that are already subject to U.S. arms embargoes, like China and Russia, will continue to face a previously existing ban on A.I. chip purchases.

All other nations — most of the world — will be subject to caps restricting the number of A.I. chips that can be imported, though countries and companies are able to increase that number by entering into special agreements with the U.S. government. The rules could rankle some foreign governments: Even countries that are close trading partners or military allies of the United States, such as Mexico, Switzerland, Poland or Israel, will face restrictions on their ability to purchase larger amounts of American A.I. products.

The rules are aimed at stopping China from obtaining from other countries the technology it needs to produce artificial intelligence, after the United States banned such sales to China in recent years.

But the regulations also have broader goals: having allied countries be the location of choice for companies to build the world’s biggest data centers, in an effort to keep the most advanced A.I. models within the borders of the United States and its partners.

Governments around the world, particularly in the Middle East, have been pumping money into attracting and building enormous data centers, in a bid to become the next center for A.I. development.

Jake Sullivan, President Biden’s national security adviser, told reporters on Sunday that the rule would ensure that the infrastructure for training the most advanced artificial intelligence would be in the United States or in the jurisdiction of close allies, and “that capacity does not get offshored like chips and batteries and other industries that we’ve had to invest hundreds of billion dollars to bring back onshore.”

Mr. Sullivan said the rule would provide “greater clarity to our international partners and to industry,” while countering national security threats from malicious actors that could use “American technologies against us.”

It will be up to the Trump administration to decide whether to keep the new rules or how to enforce them. In a call with reporters on Sunday, Biden administration officials said that the rules had bipartisan support and that they had been in consultations with the incoming administration about them.

Though companies in China have begun to develop their own A.I. chips, the global market for such semiconductors is dominated by U.S. companies, particularly Nvidia. That dominance has given the U.S. government the ability to regulate the flow of A.I. technology worldwide, by restricting U.S. company exports.

Companies have protested those limitations, saying the restrictions could hamper innocuous or even beneficial types of computing, anger U.S. allies and ultimately push global buyers into buying non-American products, like those made by China.

In a statement, Ned Finkle, Nvidia’s vice president for government affairs, called the rule “unprecedented and misguided” and said it “threatens to derail innovation and economic growth worldwide.”

“Rather than mitigate any threat, the new Biden rules would only weaken America’s global competitiveness, undermining the innovation that has kept the U.S. ahead,” he said. Nvidia’s stock dipped nearly 3 percent in premarket trading on Monday.

Brad Smith, the president of Microsoft, said in a statement that the company was confident it could “comply fully with this rule’s high security standards and meet the technology needs of countries and customers around the world that rely on us.”

In a letter to Congressional leadership on Sunday that was viewed by The New York Times, Jason Oxman, the president of the Information Technology Industry Council, a group representing tech companies, asked Congress to step in and use its authority to overturn the action if the Trump administration did not.

John Neuffer, the president of the Semiconductor Industry Association, said his group was “deeply disappointed that a policy shift of this magnitude and impact is being rushed out the door days before a presidential transition and without any meaningful input from industry.”

“The stakes are high, and the timing is fraught,” Mr. Neuffer added.

The rules, which run more than 200 pages, also set up a system in which companies that operate data centers, like Microsoft and Google, can apply for special government accreditations.

In return for following certain security standards, these companies can then trade in A.I. chips more freely around the globe. The companies will still have to agree to keep 75 percent of their total A.I. computing power within the United States or allied countries, and to locate no more than 7 percent of their computing power in any single other nation.

The rules also set up the first controls on weights for A.I. models, the parameters unique to each model that determine how artificial intelligence makes its predictions. Companies setting up data centers abroad will be required to adopt security standards to protect this intellectual property and prevent adversaries from gaining access to them.

Governments facing restrictions can raise the number of A.I. chips they can import freely by signing agreements with the U.S. government, in which they would agree to align with U.S. goals for protecting A.I.

Under the guidance of the U.S. government, Microsoft struck an agreement to partner with an Emirati firm, G42, last year, in return for G42 eliminating Huawei equipment from its systems and taking other steps.

The Biden administration could issue more rules related to chips and A.I. in the coming days, including an executive order to encourage domestic energy generation for data centers, and new rules that aim to keep the most cutting-edge chips out of China, people familiar with the deliberations said.

The latter rule comes in response to an incident last year in which U.S. officials discovered that Huawei, the sanctioned Chinese telecom firm, had been obtaining components for its A.I. chips that were manufactured by a leading Taiwanese chip firm, in violation of U.S. export controls.

The announcements are among a flurry of new regulations that the Biden administration is rushing to issue ahead of the presidential turnover as it tries to close loopholes and cement its legacy on countering China’s technological development. The administration has issued new limits on exports of chip-making equipment to China and other countries, proposed new restrictions on Chinese drones, added new Chinese companies to a military blacklist, and hurried to finalize new subsidies for U.S. chip manufacturing.

But the A.I. regulations issued Monday appear to be among the most sweeping and consequential of these actions. Artificial intelligence is quickly transforming how scientists carry out research, how companies allocate tasks between their employees and how militaries operate. While A.I. has many beneficial uses, U.S. officials have grown more concerned that it could enable the development of new weapons, help countries surveil dissidents and otherwise upend the global balance of power.

Jimmy Goodrich, a senior adviser for technology analysis at the RAND Corporation, said the rules would create a framework for protecting U.S. security interests while still allowing firms to compete abroad. “They are also forward-looking, trying to preserve U.S. and allied-led supply chains before they are offshored to the highest subsidy bidder,” he said.

Business

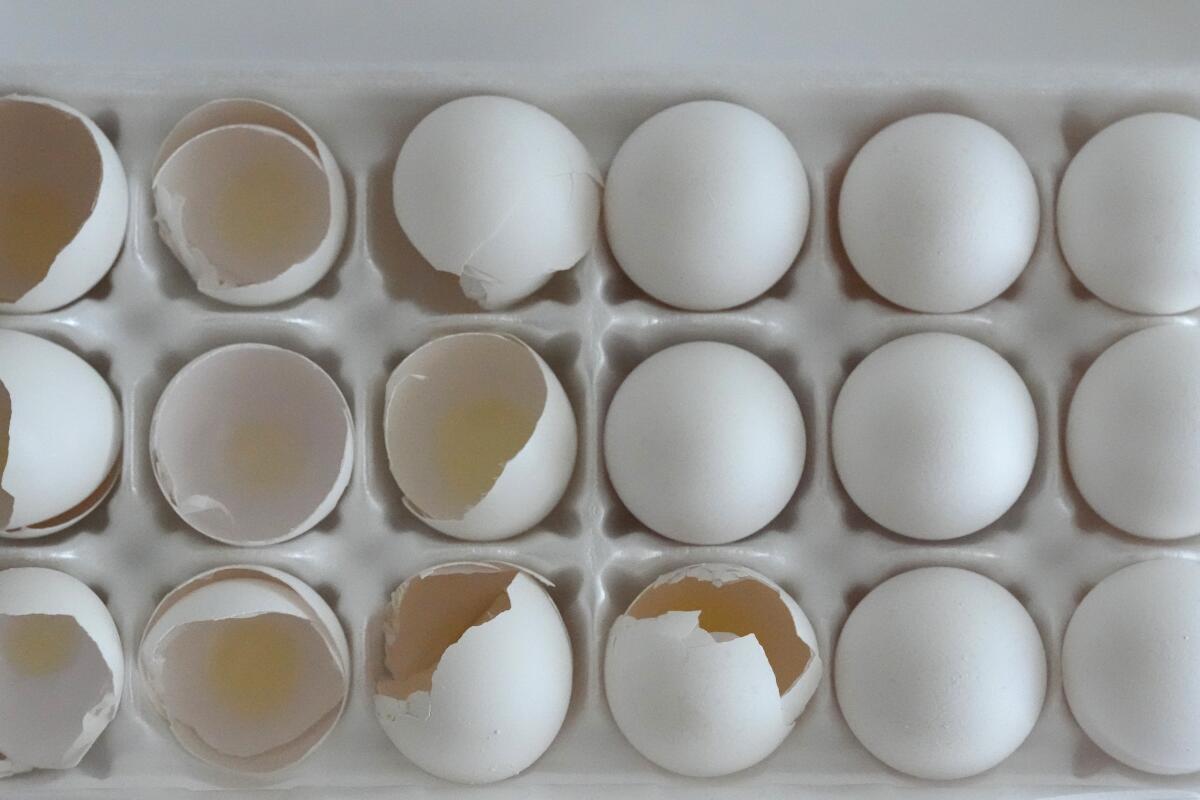

With bird flu still affecting egg prices, brunch in L.A. may soon cost more

Ongoing egg shortages in California due to the spread of bird flu among livestock are bringing another early 2025 challenge to local restaurants, especially brunch spots that rely heavily on eggs for menu items.

It’s also unclear how the ongoing fire disasters that erupted Tuesday could affect eggs and other staple ingredients. But, in light of difficult times overall for the industry and a traditionally slow January, some restaurateurs earlier this week said they have already been forced to raise prices for diners, or are weighing whether to do so, according to multiple interviews.

In San Luis Obispo, Philip Lang, who has operated Bon Temps Creole Café for nearly 30 years, said he increased the price on egg items on his menu right before Christmas. For instance, a $15 menu item now costs $17 for two eggs.

Before the bird flu outbreak, he paid $20 for a case of 15 dozen conventional eggs. Since bird flu, the price has kept doubling, starting from about $50 to now about $110 a case.

“Eggs go into all of our dishes,” he said of his restaurant that only opens for breakfast and lunch. “We make our hollandaise with eggs and dressings with eggs.”

He said most diners are understanding but some still express disappointment.

In Irvine, eggs go in just about every dish at Burnt Crumbs, from bestselling Japanese-style soufflé pancakes to the breakfast fried rice, said chef-owner Paul Cao. On an average week, Cao said his kitchen goes through 180 to 225 dozens of eggs. Cao is now having to pay more than double compared to three months ago — up to $130 for a case of 15 dozen eggs.

The H5N1 strain of the bird flu virus continues to spread across the globe, curtailing egg supply and making them more expensive and difficult to find. There’s no sign of relief, with scientists and health officials fearing we’re on the verge of another global pandemic. In California, egg prices have soared to $8.97, a 70% increase in the last month, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Cao said he doesn’t plan to raise prices for now. “I’ll give it until March — first quarter 2025, if this doesn’t trend in the right direction, we will have to raise prices. We can’t keep eating costs,” he said.

He’s afraid of losing customers but said he can’t sustain the price increase for long. “When egg prices go up $2 per dozen, that costs us a couple thousand a month,” he said.

Chef Walter Manzke, second from left, and the kitchen team at République in Los Angeles. The restaurant, like many others, is weighing increasing the cost of some egg dishes as the bird flu outbreak continues to affect egg prices.

(Ron De Angelis / For The Times)

Walter Manzke, who co-owns République with wife and partner Margarita Manzke, said he feels lucky that he can still procure good eggs from his distributor despite the shortage.

He doesn’t expect to raise prices on his menu yet but is definitely feeling the squeeze because so many of his well-known dishes use eggs — including his popular French toast.

“We’re just doing the best we can,” he said of the Hancock Park restaurant that ranked No. 4 last year on The Times’ 101 Best Restaurants in Los Angeles guide. “Compromising on quality is not an option.”

On Friday, Delilah Snell, who operates Alta Baja Market, temporarily raised prices to her egg dishes by $1 at her restaurant and market in Santa Ana.

Snell is now paying $131 for a case of 15 dozen free-range organic brown eggs. In October, she paid around $70. She said she could pay less for lower-quality eggs but doesn’t “want to compromise the quality” her customers have come to expect.

On the front counter menu of her store, she posted a sign that reads: “Over the past few weeks, our prices have gone up 40% (and are continuing to rise) because of the bird flu. As a result we need to add a $1 surcharge to all dishes with eggs to cover this expense to still provide you with a high-quality product.”

Once prices drop, she said, she’ll remove the surcharge.

The spike in egg prices comes on the heels of a slow COVID-19 pandemic recovery, as many restaurants in Southern California continue to struggle.

Lang of Bon Temps said there is now a notice on top of the menu that alerts customers to the $1 temporary increase per egg.

The notice reads: “Due to the bird flu that has caused the price of eggs to quadruple in recent months, we find it necessary to add a surcharge of a dollar per egg for all dishes containing eggs until the price of eggs comes down. We regret each time we are forced to raise any of our prices. Please know that we are not doing this for profit, only to maintain our business during these difficult times. Thank you for your understanding.”

Lang said he plans to do away with the surcharge once prices go down to about $50 for a case of 15 dozen eggs.

The cost of eggs soared by 70% in the last month in California, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

(Charles Rex Arbogast / Associated Press)

As egg prices tick up, several shoppers are also reporting shortages.

On Tuesday afternoon, Cao said the egg shelves at Song Hy market in Little Saigon in Garden Grove were more than half empty. The store, known for its inexpensive groceries, was selling cage-free medium eggs for $8.99 a dozen, according to a video he provided.

Around the same time, an egg cooler at a Trader Joe’s in Irvine was already nearly half empty after having just received a fresh shipment late that morning, one shopper said. A day earlier, at a nearby Costco, Cao said there was a line of at least 12 people waiting to grab a case of a dozen eggs from shelves that were half empty.

Some restaurant owners, such as Jasmin Gonzalez, who runs Breezy in San Juan Capistrano, have opted to raise prices on other menu items and avoid a price hike on the restaurant’s popular egg dishes.

Her restaurant — which serves a Filipino-inspired brunch — will be closed for a couple weeks for a remodel, she said, and she’ll likely raise prices on some items once it opens, mostly on higher-margin items, such as coffee. That would help the restaurant offset the price of eggs and other increased costs, including the statewide minimum-wage increase, she said.

Gonzalez said she doesn’t feel comfortable changing the price of her $14.99 breakfast burrito, a bestseller.

“I don’t want people paying $16 or $17 for breakfast burritos,” she said. “I don’t like the way that feels.”

Business

How Poshmark Is Trying to Make Resale Work Again

Lauren Eager got into thrifting in high school. It was a way to find cheap, interesting clothes while not contributing to the wastefulness of fast fashion.

In 2015, in her first year of college, she downloaded the app for Poshmark, a kind of Instagram-meets-eBay resale platform. Soon, she was selling as well as buying clothes.

This was the golden age of online reselling. In addition to Poshmark, companies like ThredUp and Depop had sprung up, giving a second life to old clothes. In 2016, Facebook debuted Marketplace. Even Goodwill got into the action, starting a snazzy website.

The platforms tapped into two consumer trends: buying stuff online and the never-gets-old delight of snagging a gently used item for a fraction of the original cost. During the Covid-19 pandemic, as people cleaned out their closets, enthusiasm for reselling intensified. It was so strong that Poshmark decided to go public. On the day of its initial public offering in January 2021, the company’s market value peaked at $7.4 billion, roughly the same as PVH’s, the company that owns Calvin Klein and Tommy Hilfiger, at the time.

Then, the business of old clothes started to fray.

Using the Poshmark app, Ms. Eager and others said, started to feel like trying to find something in a messy closet. The app was cluttered with features that did not work or that she did not use, and it felt “spammy,” she said, sending too many push notifications.

Many platforms found selling used items hard to scale. Now, online resellers are trying to recalibrate. Last year, ThredUp decided to exit Europe and focus on selling in the United States. Trove, a company that helps brands like Canada Goose and Steve Madden resell their goods, purchased a competitor, Recurate. The RealReal, a luxury consignor, appointed a new chief executive as the company tried to improve profitability.

Poshmark is undergoing perhaps the biggest reinvention. In 2023, Naver, South Korea’s biggest search engine as well as an online marketplace, bought the company in a deal valued at $1.6 billion, less than half its IPO price.

Something of a mash-up of Google and Amazon, Naver is betting it can rebuild Poshmark, which has 130 million active users, with the same technology that made Naver dominant in its own country.

It may also help breathe new life into the resale market. Analysts think the resale fashion market still has room to grow in the United States, with revenue expected to increase 26 percent to $36.3 billion by 2028, according to the retail consultancy firm Coresight Research.

New legislation in California could help. The law, passed last year, requires brands and retailers that operate in the state and generate at least $1 million to set up a “producer responsibility organization” to collect and then reuse, repair or recycle its products. Resale platforms like ThredUp and Poshmark could be in a position to help brands carry out that mandate.

At the moment, though, Naver’s focus for Poshmark is more basic: Make it a better place to sell and shop. The company has the “operating know-how” to do that, said Philip Lee, a founder of the media outlet The Pickool, which covers both South Korean and U.S. tech companies.

“They’re trying to renovate Poshmark and then expand the market share,” he said.

A Marriage of Search and Commerce

Poshmark, which is based in Redwood City, Calif., was founded in 2011 by Manish Chandra, an entrepreneur and former tech executive, and three others. In trying to expand, Poshmark faced a problem common to resellers: Capturing the excitement of the secondhand-shopping treasure hunt while not frustrating buyers with an endless scroll. The company knew it needed better search, as well as interactive elements that gave people more reasons to come beyond paying $19 for a J. Crew sweater.

For its part, Naver was looking for ways to push beyond South Korea, where its commerce and search businesses were already mature. The growing online resale market in the United States presented an opportunity, and also gave the company access to the largest consumer market in the world.

“Commerce is a big growth engine for us,” Namsun Kim, Naver’s chief financial officer, said. And the peer-to-peer sector, where users sell to one another, was still in its infancy, with room to expand. But, Mr. Kim added, “it’s a more challenging segment, and that’s why it’s harder for a lot of the larger players to enter.”

There are two common business models for resale: peer-to-peer and consignment. With consignment, a platform collects and redistributes physical goods. Poshmark uses the peer-to-peer model, which relies on scores of people — many of them novices — haggling over prices and then mailing items to one another. This decentralization can be a headache for brands, which like to maintain a certain level of control of their products. And platforms like Poshmark must make buyers comfortable with trusting the sellers on their site.

Before the Naver purchase, it was difficult to push through needed technological changes, said Vanessa Wong, the vice president of product at Poshmark.

“I would always talk to my engineers and ask, ‘What if we do this or do that?’ They’re like, ‘That’s hard. The effort’s really high,’” Ms. Wong said.

Naver’s purchase offered both the investment and the expertise to pull off the changes. Founded in 1999, the company is everywhere in South Korea.

“We are not just a simple search technology or A.I. service,” said Soo-yeon Choi, the chief executive of Naver, whose headquarters are near Seoul. The company, she said, “alleviates the frustrations of people, which is what is needed to help growth.”

Search built Naver “into the massive power that they are in Korea,” said Mr. Chandra, who stayed on as chief executive after Naver’s purchase. It was the top priority when the company bought Poshmark.

Several new elements for users and sellers have been introduced. With a tool called Posh Lens, users can take a photo of an item and, using Naver’s machine-learning technology, the site populates listings that are the same or similar to the shoe or tank top that they’re searching for. A paid ad feature for sellers called “Promoted Closet,” pushes listings higher on customer feeds.

Poshmark also introduced live shows, some of which are themed, to draw in the TikTok generation and increase engagement. One party auctioned off clothing previously worn by South Korean celebrities, a connection that was made with the help of Naver.

Still, the resale market is going through growing pains and has not quite found its footing since the height of the pandemic. It’s not clear whether the changes taking place at Poshmark will be enough. In May, Mr. Kim, Naver’s finance chief, said in an earnings call that Poshmark’s profitability was improving, but by November, the company was cautioning that growth had slowed because of weakness in the peer-to-peer resale market in North America.

Missteps and Reinvention

The company has already done some backpedaling on unpopular decisions.

In October, Poshmark introduced a new fee structure, which increased costs for buyers. Sellers, fearing that higher costs would make consumers bolt, revolted. Within weeks, the company scrapped the new fee structure.

And there are still user headaches: tags and keywords that help users find what they’re looking for can be miscategorized. Sellers sometimes tag their products incorrectly to get more eyeballs on their less popular products. (Hard-to-offload Amazon leggings, for example, may be listed as Free People apparel.)

The company is beta testing changes with its frequent sellers — people like Alex Mahl, who sells thousands of dollars in apparel on the site each year. And within dedicated Facebook groups related to Poshmark, there’s a lot of chatter about the changes that sellers and buyers would still like to see.

“The only way for it to do well is there’s going to be constant changes,” Ms. Mahl said about the tweaks on Poshmark. “If you were just on an app that never changed — one, it would be boring, and two, the opportunity to just do better wouldn’t be there.”

One recent morning, Ms. Eager, the seller who joined Poshmark back in college, was pleasantly surprised to find that the app had some new features she actually liked. She snapped a photo of her Aerie gray tank top with Posh Lens. Within seconds, the app populated listings of similar products. It was so much better than conjuring up the adjectives needed to describe it.

“Love it,” Ms. Eager exclaimed.

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoWho Are the Recipients of the Presidential Medal of Freedom?

-

Health1 week ago

Health1 week agoOzempic ‘microdosing’ is the new weight-loss trend: Should you try it?

-

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25822586/STK169_ZUCKERBERG_MAGA_STKS491_CVIRGINIA_A.jpg)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25822586/STK169_ZUCKERBERG_MAGA_STKS491_CVIRGINIA_A.jpg) Technology4 days ago

Technology4 days agoMeta is highlighting a splintering global approach to online speech

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoSeeking to heal the country, Jimmy Carter pardoned men who evaded the Vietnam War draft

-

Science2 days ago

Science2 days agoMetro will offer free rides in L.A. through Sunday due to fires

-

Movie Reviews6 days ago

Movie Reviews6 days ago‘How to Make Millions Before Grandma Dies’ Review: Thai Oscar Entry Is a Disarmingly Sentimental Tear-Jerker

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoTrump Has Reeled in More Than $200 Million Since Election Day

-

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25821992/videoframe_720397.png)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25821992/videoframe_720397.png) Technology6 days ago

Technology6 days agoLas Vegas police release ChatGPT logs from the suspect in the Cybertruck explosion