Business

Column: 99 years after the Scopes 'monkey trial,' religious fundamentalism still infects our schools

Almost a century has passed since a Tennessee schoolteacher was found guilty of teaching evolution to his students. We’ve come a long way since that happened on July 21, 1925. Haven’t we?

No, not really.

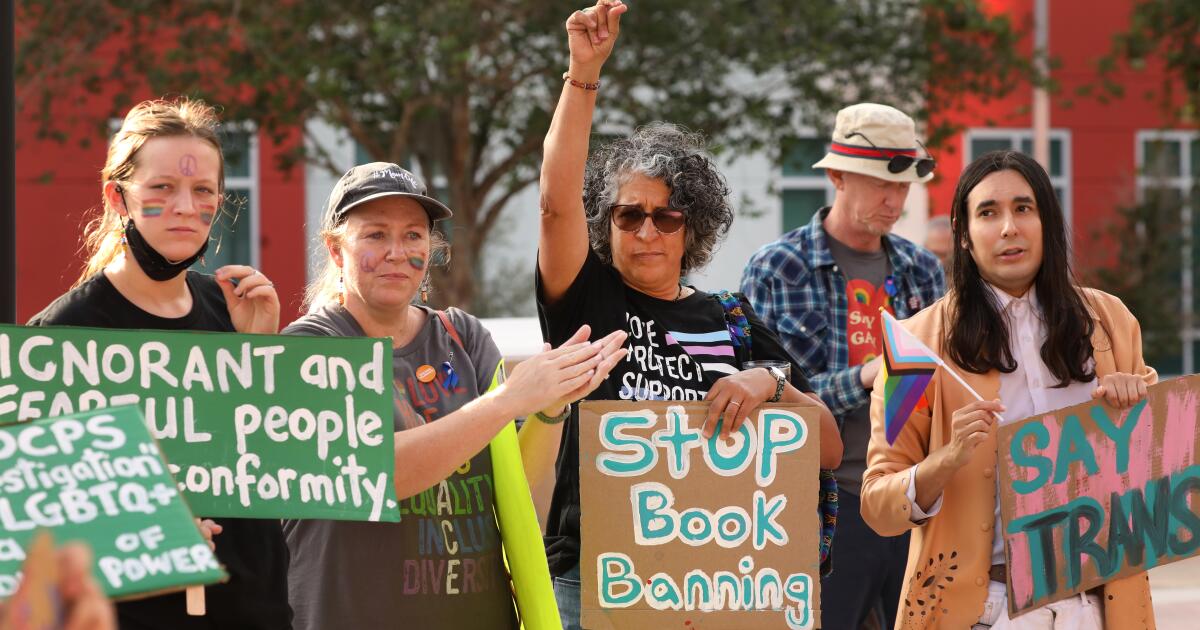

The Christian fundamentalism that begat the state law that John Scopes violated has not gone away. It regularly resurfaces in American politics, including today, when efforts to ban or dilute the teaching of evolution and other scientific concepts are part and parcel of a nationwide book-banning campaign, augmented by an effort to whitewash the teaching of American history.

I knew that education was in danger from the source that has always hampered it—religious fanaticism.

— Clarence Darrow, on why he took on the defense of John Scopes at the ‘monkey trial’

The trial in Dayton, Tenn., that supposedly placed evolution in the dock is seen as a touchstone of the recurrent battle between science and revelation. It is and it isn’t. But the battle is very real.

Let’s take a look.

The Scopes trial was one of the first, if not the very first, to be dubbed “the trial of the century.”

And why not? It pitted the fundamentalist William Jennings Bryan — three-time Democratic presidential candidate, former congressman and secretary of State, once labeled “the great commoner” for his faith in the judgment of ordinary people, but at 65 showing the effects of age — against Clarence Darrow, the most storied defense counsel of his time.

The case has retained its hold on the popular imagination chiefly thanks to “Inherit the Wind,” an inescapably dramatic reconstruction — actually a caricature — of the trial that premiered in 1955, when the play was written as a hooded critique of McCarthyism.

Most people probably know it from the 1960 film version, which starred Frederic March, Spencer Tracy and Gene Kelly as the characters meant to portray Bryan, Darrow and H.L. Mencken, the acerbic Baltimore newspaperman whose coverage of the trial is a genuine landmark of American journalism.

What all this means is that the actual case has become encrusted by myth over the ensuing decades.

One persistent myth is that the anti-evolution law and the trial arose from a focused groundswell of religious fanaticism in Tennessee. In fact, they could be said to have occurred — to repurpose a phrase usually employed to describe how Britain acquired her empire — in “a fit of absence of mind.”

The Legislature passed the measure idly as a meaningless gift to its drafter, John W. Butler, a lay preacher who hadn’t passed any other bill. (The bill “did not amount to a row of pins; let him have it,” a legislator commented, according to Ray Ginger’s definitive 1958 book about the case, “Six Days or Forever?”)

No one bothered to organize an opposition. There was no legislative debate. The lawmakers assumed that Gov. Austin Peay would simply veto the bill. The president of the University of Tennessee disdained it, but kept mum because he didn’t want the issue to complicate a plan for university funding then before the Legislature.

Peay signed the bill, asserting that it was an innocuous law that wouldn’t interfere with anything being taught in the state’s schools. The law “probably … will never be applied,” he said. Bryan, who approved of the law as a symbolic statement of religious principle, had advised legislators to leave out any penalty for violation, lest it be declared unconstitutional.

The lawmakers, however, made it a misdemeanor punishable by a fine for any teacher in the public schools “to teach any theory that denies the story of the Divine Creation of man as taught in the Bible, and to teach instead that man had descended from a lower order of animal.”

Scopes’ arrest and trial proceeded in similarly desultory manner. Scopes, a school football coach and science teacher filling in for an ailing biology teacher, assigned the students to read a textbook that included evolution. He wasn’t a local and didn’t intend to set down roots in Dayton, but his parents were socialists and agnostics, so when a local group sought to bring a test case, he agreed to be the defendant.

The play and movie of “Inherit the Wind” portray the townspeople as religious fanatics, except for a couple of courageous individuals. In fact, they were models of tolerance. Even Mencken, who came to Dayton expecting to find a squalid backwater, instead discovered “a country town full of charm and even beauty.”

Dayton’s civic boosters paid little attention to the profound issues ostensibly at play in the courthouse; they saw the trial as a sort of economic development project, a tool for attracting new residents and businesses to compete with the big city nearby, Chattanooga. They couldn’t have been happier when Bryan signed on as the chief prosecutor and a local group solicited Darrow for the defense.

“I knew that education was in danger from the source that has always hampered it — religious fanaticism,” Darrow wrote in his autobiography. “My only object was to focus the attention of the country on the programme of Mr. Bryan and the other fundamentalists in America.” He wasn’t blind to how the case was being presented in the press: “As a farce instead of a tragedy.” But he judged the press publicity to be priceless.

The press and and the local establishment had diametrically opposed visions of what the trial was about. The former saw it as a fight to protect from rubes the theory of evolution, specifically that humans descended from lower orders of primate, hence the enduring nickname of the “monkey trial.” For the judge and jury, it was about a defendant’s violation of a law written in plain English.

The trial’s elevated position in American culture derives from two sources: Mencken’s coverage for the Baltimore Sun, and “Inherit the Wind.” Notwithstanding his praise for Dayton’s “charm,” Mencken scorned its residents as “yokels,” “morons” and “ignoramuses,” trapped by their “simian imbecility” into swallowing Bryan’s “theologic bilge.”

The play and movie turned a couple of courtroom exchanges into moments of high drama, notably Darrow’s calling Bryan to the witness stand to testify to the truth of the Bible, and Bryan’s humiliation at his hands.

In truth, that exchange was a late-innings sideshow of no significance to the case. Scopes was plainly guilty of violating the law and his conviction preordained. But it was overturned on a technicality (the judge had fined him $100, more than was authorized by state law), leaving nothing for the pro-evolution camp to bring to an appellate court. The whole thing fizzled away.

The idea that despite Scopes’ conviction, the trial was a defeat for fundamentalism, lived on. Scopes was one of its adherents. “I believe that the Dayton trial marked the beginning of the decline of fundamentalism,” he said in a 1965 interview. “I feel that restrictive legislation on academic freedom is forever a thing of the past, … that the Dayton trial had some part in bringing to birth this new era.”

That was untrue then, or now. When the late biologist and science historian Stephen Jay Gould quoted that interview in a 1981 essay, fundamentalist politics were again on the rise. Gould observed that Jerry Falwell had taken up the mountebank’s mission of William Jennings Bryan.

It was harder then to exclude evolution from the class curriculum entirely, Gould wrote, but its enemies had turned to demanding “‘equal time’ for evolution and for old-time religion masquerading under the self-contradictory title of ‘scientific creationism.’”

For the evangelical right, Gould noted, “creationism is a mere stalking horse … in a political program that would ban abortion, erase the political and social gains of women … and reinstitute all the jingoism and distrust of learning that prepares a nation for demagoguery.”

And here we are again. Measures banning the teaching of evolution outright have not lately been passed or introduced at the state level. But those that advocate teaching the “strengths and weaknesses” of scientific hypotheses are common — language that seems innocuous, but that educators know opens the door to undermining pupils’ understanding of science.

In some red states, legislators have tried to bootstrap regulations aimed at narrowing scientific teaching onto laws suppressing discussions of race and gender in the classrooms and stripping books touching those topics from school libraries and public libraries.

The most ringing rejection of creationism as a public school topic was sounded in 2005 by a federal judge in Pennsylvania, who ruled that “intelligent design” — creationism by another name — “cannot uncouple itself from its creationist, and thus religious, antecedents” and therefore is unconstitutional as a topic in public schools. Yet only last year, a bill to allow “intelligent design” to be taught in the state’s public schools was overwhelmingly passed by the state Senate. (It died in a House committee.)

Oklahoma’s reactionary state superintendent of education, Ryan Walters, recently mandated that the Bible should be taught in all K-12 schools, and that a physical copy be present in every classroom, along with the Ten Commandments, the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution. “These documents are mandatory for the holistic education of students in Oklahoma,” he ordered.

It’s clear that these sorts of policies are broadly unpopular across much of the nation: In last year’s state and local elections, ibook-banners and other candidates preaching a distorted vision of “parents’ rights” to undermine educational standards were soundly defeated.

That doesn’t seem to matter to the culture warriors who have expanded their attacks on race and gender teaching to science itself. They’re playing a long game. They conceal their intentions with vague language in laws that force teachers to question whether something they say in class will bring prosecutors to the schoolhouse door.

Gould detected the subtext of these campaigns. So did Mencken, who had Bryan’s number. Crushed by his losses in three presidential campaigns in 1896, 1900 and 1908, Mencken wrote, Bryan had launched a new campaign of cheap religiosity.

“This old buzzard,” Mencken wrote, “having failed to raise the mob against its rulers, now prepares to raise it against its teachers.” Bryan understood instinctively that the way to turn American society from a democracy to a theocracy was to start by destroying its schools. His heirs, right up to the present day, know it too.

Business

Trump orders federal agencies to stop using Anthropic’s AI after clash with Pentagon

President Trump on Friday directed federal agencies to stop using technology from San Francisco artificial intelligence company Anthropic, escalating a high-profile clash between the AI startup and the Pentagon over safety.

In a Friday post on the social media site Truth Social, Trump described the company as “radical left” and “woke.”

“We don’t need it, we don’t want it, and will not do business with them again!” Trump said.

The president’s harsh words mark a major escalation in the ongoing battle between some in the Trump administration and several technology companies over the use of artificial intelligence in defense tech.

Anthropic has been sparring with the Pentagon, which had threatened to end its $200-million contract with the company on Friday if it didn’t loosen restrictions on its AI model so it could be used for more military purposes. Anthropic had been asking for more guarantees that its tech wouldn’t be used for surveillance of Americans or autonomous weapons.

The tussle could hobble Anthropic’s business with the government. The Trump administration said the company was added to a sweeping national security blacklist, ordering federal agencies to immediately discontinue use of its products and barring any government contractors from maintaining ties with it.

Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth, who met with Anthropic’s Chief Executive Dario Amodei this week, criticized the tech company after Trump’s Truth Social post.

“Anthropic delivered a master class in arrogance and betrayal as well as a textbook case of how not to do business with the United States Government or the Pentagon,” he wrote Friday on social media site X.

Anthropic didn’t immediately respond to a request for comment.

Anthropic announced a two-year agreement with the Department of Defense in July to “prototype frontier AI capabilities that advance U.S. national security.”

The company has an AI chatbot called Claude, but it also built a custom AI system for U.S. national security customers.

On Thursday, Amodei signaled the company wouldn’t cave to the Department of Defense’s demands to loosen safety restrictions on its AI models.

The government has emphasized in negotiations that it wants to use Anthropic’s technology only for legal purposes, and the safeguards Anthropic wants are already covered by the law.

Still, Amodei was worried about Washington’s commitment.

“We have never raised objections to particular military operations nor attempted to limit use of our technology in an ad hoc manner,” he said in a blog post. “However, in a narrow set of cases, we believe AI can undermine, rather than defend, democratic values.”

Tech workers have backed Anthropic’s stance.

Unions and worker groups representing 700,000 employees at Amazon, Google and Microsoft said this week in a joint statement that they’re urging their employers to reject these demands as well if they have additional contracts with the Pentagon.

“Our employers are already complicit in providing their technologies to power mass atrocities and war crimes; capitulating to the Pentagon’s intimidation will only further implicate our labor in violence and repression,” the statement said.

Anthropic’s standoff with the U.S. government could benefit its competitors, such as Elon Musk’s xAI or OpenAI.

Sam Altman, chief executive of OpenAI, the company behind ChatGPT and one of Anthropic’s biggest competitors, told CNBC in an interview that he trusts Anthropic.

“I think they really do care about safety, and I’ve been happy that they’ve been supporting our war fighters,” he said. “I’m not sure where this is going to go.”

Anthropic has distinguished itself from its rivals by touting its concern about AI safety.

The company, valued at roughly $380 billion, is legally required to balance making money with advancing the company’s public benefit of “responsible development and maintenance of advanced AI for the long-term benefit of humanity.”

Developers, businesses, government agencies and other organizations use Anthropic’s tools. Its chatbot can generate code, write text and perform other tasks. Anthropic also offers an AI assistant for consumers and makes money from paid subscriptions as well as contracts. Unlike OpenAI, which is testing ads in ChatGPT, Anthropic has pledged not to show ads in its chatbot Claude.

The company has roughly 2,000 employees and has revenue equivalent to about $14 billion a year.

Business

Video: The Web of Companies Owned by Elon Musk

new video loaded: The Web of Companies Owned by Elon Musk

By Kirsten Grind, Melanie Bencosme, James Surdam and Sean Havey

February 27, 2026

Business

Commentary: How Trump helped foreign markets outperform U.S. stocks during his first year in office

Trump has crowed about the gains in the U.S. stock market during his term, but in 2025 investors saw more opportunity in the rest of the world.

If you’re a stock market investor you might be feeling pretty good about how your portfolio of U.S. equities fared in the first year of President Trump’s term.

All the major market indices seemed to be firing on all cylinders, with the Standard & Poor’s 500 index gaining 17.9% through the full year.

But if you’re the type of investor who looks for things to regret, pay no attention to the rest of the world’s stock markets. That’s because overseas markets did better than the U.S. market in 2025 — a lot better. The MSCI World ex-USA index — that is, all the stock markets except the U.S. — gained more than 32% last year, nearly double the percentage gains of U.S. markets.

That’s a major departure from recent trends. Since 2013, the MSCI US index had bested the non-U.S. index every year except 2017 and 2022, sometimes by a wide margin — in 2024, for instance, the U.S. index gained 24.6%, while non-U.S. markets gained only 4.7%.

The Trump trade is dead. Long live the anti-Trump trade.

— Katie Martin, Financial Times

Broken down into individual country markets (also by MSCI indices), in 2025 the U.S. ranked 21st out of 23 developed markets, with only New Zealand and Denmark doing worse. Leading the pack were Austria and Spain, with 86% gains, but superior records were turned in by Finland, Ireland and Hong Kong, with gains of 50% or more; and the Netherlands, Norway, Britain and Japan, with gains of 40% or more.

Investment analysts cite several factors to explain this trend. Judging by traditional metrics such as price/earnings multiples, the U.S. markets have been much more expensive than those in the rest of the world. Indeed, they’re historically expensive. The Standard & Poor’s 500 index traded in 2025 at about 23 times expected corporate earnings; the historical average is 18 times earnings.

Investment managers also have become nervous about the concentration of market gains within the U.S. technology sector, especially in companies associated with artificial intelligence R&D. Fears that AI is an investment bubble that could take down the S&P’s highest fliers have investors looking elsewhere for returns.

But one factor recurs in almost all the market analyses tracking relative performance by U.S. and non-U.S. markets: Donald Trump.

Investors started 2025 with optimism about Trump’s influence on trading opportunities, given his apparent commitment to deregulation and his braggadocio about America’s dominant position in the world and his determination to preserve, even increase it.

That hasn’t been the case for months.

”The Trump trade is dead. Long live the anti-Trump trade,” Katie Martin of the Financial Times wrote this week. “Wherever you look in financial markets, you see signs that global investors are going out of their way to avoid Donald Trump’s America.”

Two Trump policy initiatives are commonly cited by wary investment experts. One, of course, is Trump’s on-and-off tariffs, which have left investors with little ability to assess international trade flows. The Supreme Court’s invalidation of most Trump tariffs and the bellicosity of his response, which included the immediate imposition of new 10% tariffs across the board and the threat to increase them to 15%, have done nothing to settle investors’ nerves.

Then there’s Trump’s driving down the value of the dollar through his agitation for lower interest rates, among other policies. For overseas investors, a weaker dollar makes U.S. assets more expensive relative to the outside world.

It would be one thing if trade flows and the dollar’s value reflected economic conditions that investors could themselves parse in creating a picture of investment opportunities. That’s not the case just now. “The current uncertainty is entirely man-made (largely by one orange-hued man in particular) but could well continue at least until the US mid-term elections in November,” Sam Burns of Mill Street Research wrote on Dec. 29.

Trump hasn’t been shy about trumpeting U.S. stock market gains as emblems of his policy wisdom. “The stock market has set 53 all-time record highs since the election,” he said in his State of the Union address Tuesday. “Think of that, one year, boosting pensions, 401(k)s and retirement accounts for the millions and the millions of Americans.”

Trump asserted: “Since I took office, the typical 401(k) balance is up by at least $30,000. That’s a lot of money. … Because the stock market has done so well, setting all those records, your 401(k)s are way up.”

Trump’s figure doesn’t conform to findings by retirement professionals such as the 401(k) overseers at Bank of America. They reported that the average account balance grew by only about $13,000 in 2025. I asked the White House for the source of Trump’s claim, but haven’t heard back.

Interpreting stock market returns as snapshots of the economy is a mug’s game. Despite that, at her recent appearance before a House committee, Atty. Gen. Pam Bondi tried to deflect questions about her handling of the Jeffrey Epstein records by crowing about it.

“The Dow is over 50,000 right now, she declared. “Americans’ 401(k)s and retirement savings are booming. That’s what we should be talking about.”

I predicted that the administration would use the Dow industrial average’s break above 50,000 to assert that “the overall economy is firing on all cylinders, thanks to his policies.” The Dow reached that mark on Feb. 6. But Feb. 11, the day of Bondi’s testimony, was the last day the index closed above 50,000. On Thursday, it closed at 49,499.50, or about 1.4% below its Feb. 10 peak close of 50,188.14.

To use a metric suggested by economist Justin Wolfers of the University of Michigan, if you invested $48,488 in the Dow on the day Trump took office last year, when the Dow closed at 48,448 points, you would have had $50,000 on Feb. 6. That’s a gain of about 3.2%. But if you had invested the same amount in the global stock market not including the U.S. (based on the MSCI World ex-USA index), on that same day you would have had nearly $60,000. That’s a gain of nearly 24%.

Broader market indices tell essentially the same story. From Jan. 17, 2025, the last day before Trump’s inauguration, through Thursday’s close, the MSCI US stock index gained a cumulative 16.3%. But the world index minus the U.S. gained nearly 42%.

The gulf between U.S. and non-U.S. performance has continued into the current year. The S&P 500 has gained about 0.74% this year through Wednesday, while the MSCI World ex-USA index has gained about 8.9%. That’s “the best start for a calendar year for global stocks relative to the S&P 500 going back to at least 1996,” Morningstar reports.

It wouldn’t be unusual for the discrepancy between the U.S. and global markets to shrink or even reverse itself over the course of this year.

That’s what happened in 2017, when overseas markets as tracked by MSCI beat the U.S. by more than three percentage points, and 2022, when global markets lost money but U.S. markets underperformed the rest of the world by more than five percentage points.

Economic conditions change, and often the stock markets march to their own drummers. The one thing less likely to change is that Trump is set to remain president until Jan. 20, 2029. Make your investment bets accordingly.

-

World2 days ago

World2 days agoExclusive: DeepSeek withholds latest AI model from US chipmakers including Nvidia, sources say

-

Massachusetts3 days ago

Massachusetts3 days agoMother and daughter injured in Taunton house explosion

-

Montana1 week ago

Montana1 week ago2026 MHSA Montana Wrestling State Championship Brackets And Results – FloWrestling

-

Louisiana5 days ago

Louisiana5 days agoWildfire near Gum Swamp Road in Livingston Parish now under control; more than 200 acres burned

-

Denver, CO3 days ago

Denver, CO3 days ago10 acres charred, 5 injured in Thornton grass fire, evacuation orders lifted

-

Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoYouTube TV billing scam emails are hitting inboxes

-

Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoStellantis is in a crisis of its own making

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoOpenAI didn’t contact police despite employees flagging mass shooter’s concerning chatbot interactions: REPORT