Business

As inflation soars, how is AriZona iced tea still 99 cents?

Gasoline is almost six bucks a gallon. Groceries are 8% increased than final yr. Greenback shops: now dollar-and-a-quarter shops.

However an enormous, 23-ounce can of AriZona iced tea nonetheless prices 99 cents, the identical worth it has been because it hit the market 30 years in the past. At this time, that’s cheaper than most bottled water, 20-ounce sodas, iced teas and canned coffees available on the market. In the event you might fill your automotive up with cans of AriZona Inexperienced Tea with Ginseng and Honey, it might be cheaper than L.A. gasoline by almost 40 cents a gallon.

How does AriZona pull this off whereas every little thing else goes up? The worth of aluminum has doubled within the final 18 months. The worth of excessive fructose corn syrup has tripled since 2000. Gasoline costs are pumping up supply prices. One 1992 greenback, adjusted for inflation, is price two 2022 {dollars}. However the 99-cent Huge AZ Can, as the corporate calls it, persists.

The quick reply: the corporate is making much less cash. The massive cans are nonetheless worthwhile, however for the second, they’re a lot much less so than a number of years in the past.

Don Vultaggio, the 70-year-old, 6-foot-8 founder and chairman of the corporate, is selecting to take a haircut as a way to preserve the worth flat and cans transferring.

“I’m dedicated to that 99 cent worth — when issues go towards you, you tighten your belt,” Vultaggio stated on a Zoom name in early April from his headquarters on Lengthy Island, N.Y. Regardless that his prices are increased, “I don’t need to do what the bread guys and the gasoline guys and everyone else are doing,” Vultaggio stated. “Shoppers don’t want one other worth improve from a man like me.”

He has the facility to make a name like that as a result of AriZona is without doubt one of the few impartial personal corporations remaining within the consolidated world of nonalcoholic packaged drinks, a market dominated by PepsiCo, Coca-Cola, and Keurig Dr Pepper, which owns Snapple.

Vultaggio, a Brooklyn native with the accent to show it, bought the concept for the tea firm when he was working his route as a beer distributor in Manhattan. He seen that folks had been ingesting Snapple, regardless that it was freezing outdoors. He determined to get into the iced tea enterprise then and there.

At this time, he co-owns the corporate in its entirety together with his sons, Spencer and Wesley, who function chief advertising and marketing officer and chief inventive officer, respectively, and joined him on the decision. Forbes places their mixed web price at over $4 billion, all from AriZona, inserting them among the many thousand richest folks on this planet.

AriZona spends much less on advertising and marketing than different beverage manufacturers. With a can this recognizable, who wants commercials?

(Myung J. Chun / Los Angeles Instances)

The corporate sells about 1 billion 99-cent cans every year, Vultaggio stated, which makes up about 25% of its whole income. Its fruit drinks, power drinks, bottled teas, snacks, onerous seltzer, and different choices transfer much less quantity, however have increased costs and better margins.

When Vultaggio began out, Snapple additionally charged 99 cents for its signature 16-ounce glass bottles. AriZona was cheaper, however solely as a result of it contained 50% extra tea per can. Now, a Snapple’s $1.79. An 18.5-ounce container of Gold Peak, Coke’s model, prices $1.99. Pure Leaf, the upscale Pepsi-Lipton label, goes for $2.09.

AriZona merchandise commanded almost 16% of the ready-to-drink tea market within the U.S. by quantity in 2020, second solely to PepsiCo’s slate of Lipton, Pure Leaf, and Brisk. That quantities to 255 million gallons of AriZona iced tea bought, based on information from Beverage Advertising Corp. — sufficient to fill Echo Park Lake 10 instances over.

Vultaggio’s calculation is that elevating costs and dropping clients within the course of simply isn’t definitely worth the short-term revenue. “Your organization has to take care of value will increase, however your clients need to take care of value will increase too,” Vultaggio stated. “And should you break their again, no one wins.”

AriZona’s 30-year run at 99 cents is outstanding, however the report for longest-holding beverage worth nonetheless goes to Coca-Cola, which held the price of a 6.5-ounce bottle at 5 cents for greater than 70 years, from 1886 to 1959.

The Nickel Coke phenomenon developed in a special retail period, and grew out of a collection of accidents: first, Coca-Cola agreed to promote its syrup to bottlers at a set worth in perpetuity, considering bottling was only a fad. Then, when the corporate managed to renegotiate, there was a lot five-cent worth promoting and so many merchandising machines that solely accepted nickels that it took one other couple of a long time earlier than Coca-Cola might break the nickel’s spell. The top end result, nevertheless, was a world-spanning mushy drink empire geared towards quantity, not margins.

Extra usually, economists have proven that costs that finish with a 9 are extra resistant to alter throughout the market, even when inflation is raging. Haipeng (Allan) Chen, a professor of selling on the College of Kentucky’s Gatton Faculty of Enterprise and Economics, studied what occurred to costs in Israel throughout a interval of runaway inflation within the Nineteen Eighties.

“In the event you take a look at these 9s, they’re far more inflexible,” Chen stated, as retailers resist edging up by one or two cents and dropping the supposed psychological advantage of that last 9. However once they do bounce, they bounce massive — 10 cents, to land on one other 9, and even additional. Surprisingly, this affinity for 9s holds even in on-line purchasing, wherein digital funds don’t require actual change.

Vultaggio has his personal clarification for the 99-cent attraction. “It’s been like that since cavemen, the 99-cent worth level was thrilling then, and it’s thrilling right this moment,” Vultaggio stated. “One thing beneath a greenback is enticing,” and realizing precisely how far more a drink goes so as to add to your lunch provides a way of safety. “I began out as a blue collar man, and budgeting your funds every day was part of life.”

One other dynamic is probably going in play with AriZona’s sticky worth: a way of belief. “It’s like a price-matching assure,” Chen stated, “it says: belief me, I’ll handle you, I’m not charging a horrendous worth.”

Don Vultaggio co-owns the corporate together with his sons, Wesley, left, and Spencer, who function chief inventive officer and chief advertising and marketing officer, respectively.

(Nicole Corso )

AriZona has been dedicated to 99 cents since 1996, when it began printing the worth immediately on cans to cease retailers from elevating costs on their very own. But it surely’s powerful to run a worthwhile enterprise with a set worth. AriZona has used scale, expertise and fixed tweaks to the enterprise to maintain prices down and revenues rising over the previous 30 years.

Among the key adjustments, Vultaggio stated: again within the day, just one manufacturing unit made the massive cans — now, there are a number of suppliers competing on worth, and might expertise has modified to scale back the quantity of aluminum in every by 40%. The corporate has streamlined operations, utilizing its personal manufacturing unit in New Jersey, which might churn out 1,500 cans per minute, for a lot of its product. Firm vans principally make deliveries in the course of the evening to keep away from site visitors.

However the economics proper now are brutal.

The corporate expenses wholesale distributors a bit of greater than $12 per 24-can case, or 50 cents a can (AriZona declined to share how a lot it expenses retailers it distributes to immediately, however distributors cost about 70 cents per can to their clients). With simply that stack of pennies to work with, each cent counts.

The price of aluminum has doubled within the final 18 months, from about $1,750 per metric ton to just about $3,250 right this moment. Transport, taxes, and different bills for aluminum ingots up the worth once more — and people premiums elevated from about $420 per ton in April 2019 to greater than $880 right this moment.

With about 23 grams of aluminum per Huge AZ Can, which means the worth of steel alone has gone from almost 5 cents as much as 9.5 cents a pop — if you’re promoting a billion cans a yr, that’s $45 million down the tubes.

The Vultaggios declined to interrupt down precisely how a lot their prices have risen per can. They did say that the corporate sometimes hedged aluminum costs to offset prices, however these hedges expired. Now, it’s uncovered to the total brunt of the worldwide commodity worth.

The costs of tea, water, excessive fructose corn syrup, honey, citric acid, and flavorings have remained pretty flat in recent times, however over the long run the stress has grown. Excessive fructose corn syrup has risen from round 15 cents per pound on the flip of the century to greater than 45 cents right this moment, based on the U.S. Division of Agriculture, amounting to one thing like a 3-cent value improve per can within the final 20 years. That small change, instances a billion, equals a further $30 million eaten away.

Certainly one of AriZona’s largest value financial savings isn’t within the can or the corn syrup, nevertheless: it’s within the advertising and marketing.

“Most manufacturers in America right this moment consider they need to exit and have a Tremendous Bowl industrial or do conventional promoting,” Vultaggio stated. “After we first began, I didn’t have the cash for that — so every can needed to be like a billboard. That’s why I selected the large can. It stood tall.”

The attention-melting coloration mixtures on the labels had been designed with the identical aim in thoughts. To at the present time, the corporate has stored its advertising and marketing funds to a minimal and its complete operation lean, with solely about 350 folks on workers at its headquarters and 1,500 companywide.

The model title itself, and the pastel Southwest coloration scheme, had been impressed by the aesthetics of Don’s spouse, Ilene, who had already redone their dwelling in a seaside New York Metropolis neighborhood in faux-adobe model by the point Don began the corporate.

“The title Arizona got here to me as a result of Arizona, once I was a child was, it was dry. It was wholesome. You had bronchial asthma, you moved to Arizona,” Vultaggio stated. Ilene got here up with the capital Z in the course of the title. “Then it turned comfy to clients, as a result of they’d heard of Arizona, so we bought that type of glow.”

Vultaggio didn’t make it to the Grand Canyon State himself till 1995 or so, however famous that he thinks the iced tea’s success has helped the state’s model, at this level.

And the corporate has seen each the great and dangerous of its robust 99-cent model play out in recent times. On the one hand, its low-cost and never-changing branding has turned it right into a recognizable icon — the corporate can promote bucket hats and hoodies emblazoned with its can designs, Adidas has made an AriZona shoe, and for a complete month in 2019, superstar chef Danny Bowien, of Mission Chinese language meals, turned his Brooklyn restaurant into an AriZona zone, with inexperienced tea and grapeade dishes and “Nice Purchase! 99¢” signage.

However when pictures of its Canadian cans — which promote for $1.29 Canadian — make the rounds on-line, folks are likely to freak. A tweet that stated, “If this world is coming, I don’t need to dwell in it,” with a photograph of a $1.29 Canadian can, went viral in 2021. The corporate needed to take to Twitter to reassure its clients, explaining the idea of change charges. “Don’t fear fam,” the iced tea firm wrote. “We nonetheless bought you.”

Business

In Los Angeles, Hotels Become a Refuge for Fire Evacuees

The lobby of Shutters on the Beach, the luxury oceanfront hotel in Santa Monica that is usually abuzz with tourists and entertainment professionals, had by Thursday transformed into a refuge for Los Angeles residents displaced by the raging wildfires that have ripped through thousands of acres and leveled entire neighborhoods to ash.

In the middle of one table sat something that has probably never been in the lobby of Shutters before: a portable plastic goldfish tank. “It’s my daughter’s,” said Kevin Fossee, 48. Mr. Fossee and his wife, Olivia Barth, 45, had evacuated to the hotel on Tuesday evening shortly after the fire in the Los Angeles Pacific Palisades area flared up near their home in Malibu.

Suddenly, an evacuation alert came in. Every phone in the lobby wailed at once, scaring young children who began to cry inconsolably. People put away their phones a second later when they realized it was a false alarm.

Similar scenes have been unfolding across other Los Angeles hotels as the fires spread and the number of people under evacuation orders soars above 100,000. IHG, which includes the Intercontinental, Regent and Holiday Inn chains, said 19 of its hotels across the Los Angeles and Pasadena areas were accommodating evacuees.

The Palisades fire, which has been raging since Tuesday and has become the most destructive in the history of Los Angeles, struck neighborhoods filled with mansions owned by the wealthy, as well as the homes of middle-class families who have owned them for generations. Now they all need places to stay.

Many evacuees turned to a Palisades WhatsApp group that in just a few days has grown from a few hundred to over 1,000 members. Photos, news, tips on where to evacuate, hotel discount codes and pet policies were being posted with increasing rapidity as the fires spread.

At the midcentury modern Beverly Hilton hotel, which looms over the lawns and gardens of Beverly Hills, seven miles and a world away from the ash-strewed Pacific Palisades, parking ran out on Wednesday as evacuees piled in. Guests had to park in another lot a mile south and take a shuttle back.

In the lobby of the hotel, which regularly hosts glamorous events like the recent Golden Globe Awards, guests in workout clothes wrestled with children, pets and hastily packed roll-aboards.

Many of the guests were already familiar with each other from their neighborhoods, and there was a resigned intimacy as they traded stories. “You can tell right away if someone is a fire evacuee by whether they are wearing sweats or have a dog with them,” said Sasha Young, 34, a photographer. “Everyone I’ve spoken with says the same thing: We didn’t take enough.”

The Hotel June, a boutique hotel with a 1950s hipster vibe a mile north of Los Angeles International Airport, was offering evacuees rooms for $125 per night.

“We were heading home to the Palisades from the airport when we found out about the evacuations,” said Julia Morandi, 73, a retired science educator who lives in the Palisades Highlands neighborhood. “When we checked in, they could see we were stressed, so the manager gave us drinks tickets and told us, ‘We take care of our neighbors.’”

Hotels are also assisting tourists caught up in the chaos, helping them make arrangements to fly home (as of Friday, the airport was operating normally) and waiving cancellation fees. A spokeswoman for Shutters said its guests included domestic and international tourists, but on Thursday, few could be spotted among the displaced Angelenos. The heated outdoor pool that overlooks the ocean and is usually surrounded by sunbathers was completely deserted because of the dangerous air quality.

“I think I’m one of the only tourists here,” said Pavel Francouz, 34, a hockey scout who came to Los Angeles from the Czech Republic for a meeting on Tuesday before the fires ignited.

“It’s weird to be a tourist,” he said, describing the eerily empty beaches and the hotel lobby packed with crying children, families, dogs and suitcases. “I can’t imagine what it would feel like to be these people,” he said, adding, “I’m ready to go home.”

Follow New York Times Travel on Instagram and sign up for our weekly Travel Dispatch newsletter to get expert tips on traveling smarter and inspiration for your next vacation. Dreaming up a future getaway or just armchair traveling? Check out our 52 Places to Go in 2025.

Business

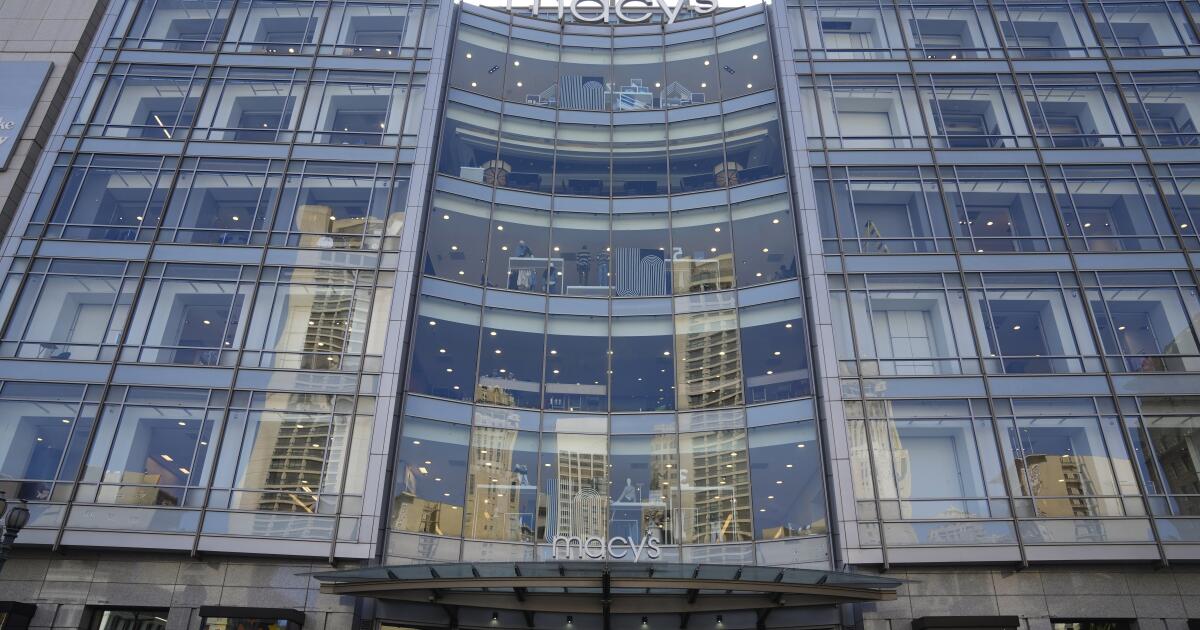

Downtown Los Angeles Macy's is among 150 locations to close

The downtown Los Angeles Macy’s department store, situated on 7th Street and a cornerstone of retail in the area, will shut down as the company prepares to close 150 underperforming locations in an effort to revamp and modernize its business.

The iconic retail center announced this week the first 66 closures, including nine in California spanning from Sacramento to San Diego. Stores will also close in Florida, New York and Georgia, among other states. The closures are part of a broader company strategy to bolster sustainability and profitability.

Macy’s is not alone in its plan to slim down and rejuvenate sales. The retailer Kohl’s announced on Friday that it would close 27 poor performing stores by April, including 10 in California and one in the Los Angeles neighborhood of Westchester. Kohl’s will also shut down its San Bernardino e-commerce distribution center in May.

“Kohl’s continues to believe in the health and strength of its profitable store base” and will have more than 1,100 stores remaining after the closures, the company said in a statement.

Macy’s announced its plan last February to end operations at roughly 30% of its stores by 2027, following disappointing quarterly results that included a $71-million loss and nearly 2% decline in sales. The company will invest in its remaining 350 stores, which have the potential to “generate more meaningful value,” according to a release.

“We are closing underproductive Macy’s stores to allow us to focus our resources and prioritize investments in our go-forward stores, where customers are already responding positively to better product offerings and elevated service,” Chief Executive Tony Spring said in a statement. “Closing any store is never easy.”

Macy’s brick-and-mortar locations also faced a setback in January 2024, when the company announced the closures of five stores, including the location at Simi Valley Town Center. At the same time, Macy’s said it would layoff 3.5% of its workforce, equal to about 2,350 jobs.

Farther north, Walgreens announced this week that it would shutter 12 stores across San Francisco due to “increased regulatory and reimbursement pressures,” CBS News reported.

Business

The justices are expected to rule quickly in the case.

When the Supreme Court hears arguments on Friday over whether protecting national security requires TikTok to be sold or closed, the justices will be working in the shadow of three First Amendment precedents, all influenced by the climate of their times and by how much the justices trusted the government.

During the Cold War and in the Vietnam era, the court refused to credit the government’s assertions that national security required limiting what newspapers could publish and what Americans could read. More recently, though, the court deferred to Congress’s judgment that combating terrorism justified making some kinds of speech a crime.

The court will most likely act quickly, as TikTok faces a Jan. 19 deadline under a law enacted in April by bipartisan majorities. The law’s sponsors said the app’s parent company, ByteDance, is controlled by China and could use it to harvest Americans’ private data and to spread covert disinformation.

The court’s decision will determine the fate of a powerful and pervasive cultural phenomenon that uses a sophisticated algorithm to feed a personalized array of short videos to its 170 million users in the United States. For many of them, and particularly younger ones, TikTok has become a leading source of information and entertainment.

As in earlier cases pitting national security against free speech, the core question for the justices is whether the government’s judgments about the threat TikTok is said to pose are sufficient to overcome the nation’s commitment to free speech.

Senator Mitch McConnell, Republican of Kentucky, told the justices that he “is second to none in his appreciation and protection of the First Amendment’s right to free speech.” But he urged them to uphold the law.

“The right to free speech enshrined in the First Amendment does not apply to a corporate agent of the Chinese Communist Party,” Mr. McConnell wrote.

Jameel Jaffer, the executive director of the Knight First Amendment Institute at Columbia University, said that stance reflected a fundamental misunderstanding.

“It is not the government’s role to tell us which ideas are worth listening to,” he said. “It’s not the government’s role to cleanse the marketplace of ideas or information that the government disagrees with.”

The Supreme Court’s last major decision in a clash between national security and free speech was in 2010, in Holder v. Humanitarian Law Project. It concerned a law that made it a crime to provide even benign assistance in the form of speech to groups said to engage in terrorism.

One plaintiff, for instance, said he wanted to help the Kurdistan Workers’ Party find peaceful ways to protect the rights of Kurds in Turkey and to bring their claims to the attention of international bodies.

When the case was argued, Elena Kagan, then the U.S. solicitor general, said courts should defer to the government’s assessments of national security threats.

“The ability of Congress and of the executive branch to regulate the relationships between Americans and foreign governments or foreign organizations has long been acknowledged by this court,” she said. (She joined the court six months later.)

The court ruled for the government by a 6-to-3 vote, accepting its expertise even after ruling that the law was subject to strict scrutiny, the most demanding form of judicial review.

“The government, when seeking to prevent imminent harms in the context of international affairs and national security, is not required to conclusively link all the pieces in the puzzle before we grant weight to its empirical conclusions,” Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. wrote for the majority.

In its Supreme Court briefs defending the law banning TikTok, the Biden administration repeatedly cited the 2010 decision.

“Congress and the executive branch determined that ByteDance’s ownership and control of TikTok pose an unacceptable threat to national security because that relationship could permit a foreign adversary government to collect intelligence on and manipulate the content received by TikTok’s American users,” Elizabeth B. Prelogar, the U.S. solicitor general, wrote, “even if those harms had not yet materialized.”

Many federal laws, she added, limit foreign ownership of companies in sensitive fields, including broadcasting, banking, nuclear facilities, undersea cables, air carriers, dams and reservoirs.

While the court led by Chief Justice Roberts was willing to defer to the government, earlier courts were more skeptical. In 1965, during the Cold War, the court struck down a law requiring people who wanted to receive foreign mail that the government said was “communist political propaganda” to say so in writing.

That decision, Lamont v. Postmaster General, had several distinctive features. It was unanimous. It was the first time the court had ever held a federal law unconstitutional under the First Amendment’s free expression clauses.

It was the first Supreme Court opinion to feature the phrase “the marketplace of ideas.” And it was the first Supreme Court decision to recognize a constitutional right to receive information.

That last idea figures in the TikTok case. “When controversies have arisen,” a brief for users of the app said, “the court has protected Americans’ right to hear foreign-influenced ideas, allowing Congress at most to require labeling of the ideas’ origin.”

Indeed, a supporting brief from the Knight First Amendment Institute said, the law banning TikTok is far more aggressive than the one limiting access to communist propaganda. “While the law in Lamont burdened Americans’ access to specific speech from abroad,” the brief said, “the act prohibits it entirely.”

Zephyr Teachout, a law professor at Fordham, said that was the wrong analysis. “Imposing foreign ownership restrictions on communications platforms is several steps removed from free speech concerns,” she wrote in a brief supporting the government, “because the regulations are wholly concerned with the firms’ ownership, not the firms’ conduct, technology or content.”

Six years after the case on mailed propaganda, the Supreme Court again rejected the invocation of national security to justify limiting speech, ruling that the Nixon administration could not stop The New York Times and The Washington Post from publishing the Pentagon Papers, a secret history of the Vietnam War. The court did so in the face of government warnings that publishing would imperil intelligence agents and peace talks.

“The word ‘security’ is a broad, vague generality whose contours should not be invoked to abrogate the fundamental law embodied in the First Amendment,” Justice Hugo Black wrote in a concurring opinion.

The American Civil Liberties Union told the justices that the law banning TikTok “is even more sweeping” than the prior restraint sought by the government in the Pentagon Papers case.

“The government has not merely forbidden particular communications or speakers on TikTok based on their content; it has banned an entire platform,” the brief said. “It is as though, in Pentagon Papers, the lower court had shut down The New York Times entirely.”

Mr. Jaffer of the Knight Institute said the key precedents point in differing directions.

“People say, well, the court routinely defers to the government in national security cases, and there is obviously some truth to that,” he said. “But in the sphere of First Amendment rights, the record is a lot more complicated.”

-

Culture1 week ago

Culture1 week agoThe 25 worst losses in college football history, including Baylor’s 2024 entry at Colorado

-

Sports1 week ago

Sports1 week agoThe top out-of-contract players available as free transfers: Kimmich, De Bruyne, Van Dijk…

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoNew Orleans attacker had 'remote detonator' for explosives in French Quarter, Biden says

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoCarter's judicial picks reshaped the federal bench across the country

-

Politics6 days ago

Politics6 days agoWho Are the Recipients of the Presidential Medal of Freedom?

-

Health5 days ago

Health5 days agoOzempic ‘microdosing’ is the new weight-loss trend: Should you try it?

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoSouth Korea extends Boeing 737-800 inspections as Jeju Air wreckage lifted

-

News1 week ago

News1 week ago21 states are getting minimum wage bumps in 2025