Lifestyle

Supermodel Carol Alt ‘Memba Her?!

American model Carol Alt was only 22 years old — and 5′ 11″ — when she shot to stardom after she was featured on the cover of the 1982 Sports Illustrated Swimsuit issue.

Alt was featured in Vogue, Harper’s Bazaar, Elle and Cosmopolitan, as well as, scoring sought after ad campaigns like Cover Girl, Hanes, Givenchy and Diet Pepsi.

Lifestyle

A daughter reexamines her own family story in ‘The Mixed Marriage Project’

Dorothy Roberts (left) is the George A. Weiss university professor of law & sociology at the University of Pennsylvania. Her parents, Robert and Iris, married in the 1950s.

Cris Crisman/Simon & Schuster; Dorothy Roberts

hide caption

toggle caption

Cris Crisman/Simon & Schuster; Dorothy Roberts

Almost a decade after her father’s death, legal scholar Dorothy Roberts still had 25 boxes of his research that she had yet to sort through. When she moved from Chicago to Philadelphia, she brought the boxes — and finally opened them.

Roberts’ father, Robert Roberts, was a white anthropologist who spent his career at Roosevelt University in Chicago. The boxes contained transcripts of nearly 500 interviews he had conducted with interracial couples across the city, including interviews with couples who were married in the late 1800s, all the way to couples who are married in the 1960s.

“They were absolutely fascinating,” Roberts says of the transcripts. “I learned so much about the racial caste system in Chicago, the Color Line, the Black Belt.”

Initially, Roberts saw the project as a chance to finish her father’s work, but as she examined the documents, she learned more about her own family — including the fact that her mother, Iris, a Black Jamaican immigrant, had assisted in her husband’s research.

“When I got to the 1950s interviews, I discovered that my mother was conducting all the interviews of the wives, while my father conducted the interviews for the husbands,” Roberts says. “Finding out that my mother was involved … created curiosity I had about my family, about their marriage, and then I began to think about how it related to me and my identity as a Black girl with a white father.”

In her new book, The Mixed Marriage Project: A Memoir of Love, Race, and Family, Roberts dives into her parents’ research and her surprise at learning that she was included as participant number 224 in the files. She also shares her own thoughts on interracial relationships.

“My father thought that interracial intimacy was the instrument to end racism, and I think it’s really flipped the other way,” she says. “We end racism when we will see the possibility of truly being able to love each other as equal human beings.”

Interview highlights

The Mixed Marriage Project, by Dorothy Roberts

Simon & Schuster

hide caption

toggle caption

Simon & Schuster

On white European immigrant women marrying Black men in the early 20th century

These were immigrant women coming from Europe who had no familiarity at all with the racial caste system in Chicago. … So when they marry Black men, in fact, they thought that marrying an American citizen would help them assimilate into American culture. So they had no idea … that if they married a Black man, it would do the opposite to them. They would be lower in their status than they were as white immigrants. And so many of them would say, “I found out that I had to live in a colored neighborhood. I had to leave my white neighbors. I had left my family in order to marry this Black man and move into the Black Belt. I now couldn’t even tell my employer my address, because if they found out my address, they’d know I must be living with a Black man.” Why else would a white woman be living in the Black Belt?

They were afraid they would lose their jobs, and many reported that they were fired as a result of their employer finding out that they were married to a Black man. They were met with stares when they got on the streetcar. Many said that if they were going on a streetcar in Chicago, they would go on separately and pretend they didn’t know each other so that no one would know that they were married.

On the difference between her father’s and mother’s notes in the project

My father, much to my horror, was very anthropological in terms of the physical traits of the people he interviewed. He wrote about the “Negroid traits” and whether the child had any trace of “Negroid blood” and that sort of thing. Again, remembering he was doing this in the 1930s.

My mother was much more interested in the personality traits of the people she interviewed and what their furniture looked like and her own emotions. And there’s just so many delightful things. The way in which she interacts with the children when she’s interviewing the wives — there’s a lot more attention to what the children are doing. I can’t remember a single interview where my father really describes the children’s behavior. He describes their physical appearance, but my mother would describe their behavior and their interaction with the mother. All of that is part of the interview and her notes, and she writes it almost like a screenplay. It’s really, really wonderful to read.

On the fetishization of interracial intimacy and biracial children

There was this visceral feeling I felt whenever a Black man, a Black husband, would talk about his preference for being with white women. These ideas that interracial intimacy has an extra excitement to it. It has an extra titillation to it — that kind of idea came up in many of the interviews — and I just have a very visceral revulsion at that kind idea, a sort of a fetishization of interracial intimacy and also of biracial children. The idea that whitening children makes them more attractive or makes them more intelligent or more appealing, more lovable. And whenever that came up, I just, sometimes I had to just throw the interview down because I couldn’t stand that kind of thinking.

On her decision to identify as Black in college and hide her dad’s whiteness

I now regret that I hid the fact that my father was white, that I denied him that part of my identity or denied the reality that he was part of my identity. … I think I very wrongly believed that if they knew my father was white, I somehow wouldn’t be as much an integral part of these groups, that they might feel differently about me. …

I realized by the end of working on the memoir that I am a Black woman with a white father [and] I should not deny all that my father contributed to my identity. I would not be the Black woman I am today, I probably would not have done the work against racism and against the demeaning of Black women, I would have not done the [work] to uplift Black women if it weren’t for my father and all that he taught me. And I need to appreciate and acknowledge all that my father contributed to the Black woman I am today.

On what this project has taught her about love and race

It showed me more powerfully than anything I’d ever read before how the invention of race, the lie that human beings are naturally divided into races, can erase the very ties of family. … In my own case, my father’s younger brother, my uncle Edward, disowned him when he married my mother. And even though he lived in the Chicago area and I had cousins who lived there, I never met them because of this rift, this divide between my father and his brother.

Working on the memoir also made me realize that all the work I’ve been doing throughout my career was trying to answer this question of, what does it take to love across the chasm of race? That’s what these couples are telling us, even the ones who were still racist. … They’re telling us what it takes to challenge and dismantle structural racism in America. And so, to me, these interviews persuaded me even more that we can believe in our common humanity. We can overcome the seemingly unbreakable, unshakable shackles of structural racism. But it can’t be simply by pretending that the sentiment of love or even loving someone across the racial lines will do it. We have to see the work that it’s going to take to do that.

Anna Bauman and Nico Gonzalez Wisler produced and edited this interview for broadcast. Bridget Bentz, Molly Seavy-Nesper and Meghan Sullivan adapted it for the web.

Lifestyle

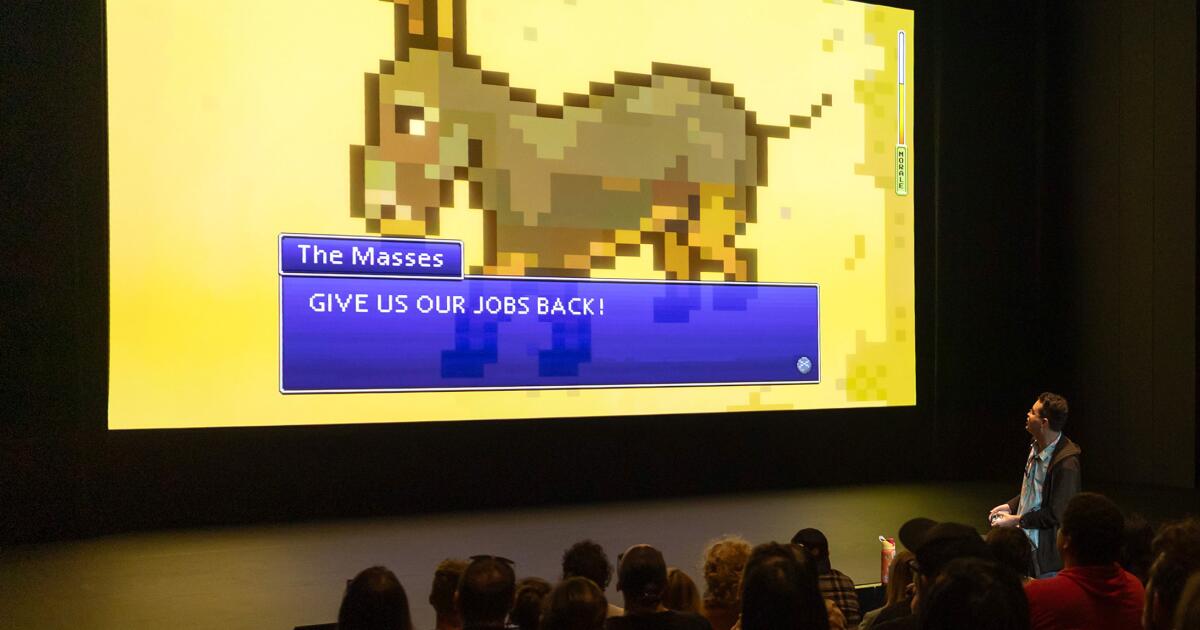

What playing a 7-hour video game with strangers in L.A. taught me about the resistance

The donkeys are pissed off. Put upon, out of work and victims of decades-long systemic abuse, it’s time, they have decided, to protest.

The donkeys, metaphorically, are us.

At least that’s the premise of “asses.masses,” a video game played by and for a live audience. It’s theater for the post-Twitch age, performance art for those weaned on “The Legend of Zelda” or “Pokémon.” Most important, it’s entertainment as political dissent for these divisive times. Though the project dates to 2018, it’s hard not to draft 2026 onto its narrative. Whether it’s unjust incarceration, mass layoffs or topics centered around tech’s automation of jobs, “asses.masses,” despite generally lasting more than seven hours — yes, seven-plus hours — is a work of urgency.

The audience cheers various decisions made during the playing of “asses.masses” at UCLA Nimoy Theater.

(Myung J. Chun / Los Angeles Times)

And for the audience at the Saturday showing at the UCLA Nimoy Theater, it felt like a call to arms. Citizens executed in the street for exercising their right to free speech? That’s in here. Run-ins with authorities that recall images seen in multiple American cities over the past few months? Also in here, albeit in a retro, pixel art style that may bring to mind the “Final Fantasy” series from its Super Nintendo days.

In a city that’s been ravaged by fires, ICE raids and a series of entertainment industry layoffs, the sold-out crowd of nearly 300 was riled up. Chants of “ass power!” — the donkey’s protest slogan — were heard throughout the day as attendees politely gathered near a single video game controller on a dais to play the game, becoming not just the avatar for the donkeys but a momentary leader for the collective. Cheers would erupt when a young donkey reached the conclusion that “I kinda think the system is rigged against everyone.” And when technological advances, clearly a stand-in for artificial intelligence, were described as “evil, soulless, job-taking, child-killing machines,” there were knowing claps, as if no exaggeration was stated.

“Our theater is supposed to be a rehearsal for life,” says Patrick Blenkarn, who co-created the game with Milton Lim, interdisciplinary artists from Canada who often work with interactive media.

“We grew up in a radical political tradition of theater,” says Patrick Blenkarn, right, who co-created “asses.masses” with Milton Lim.

(Myung J. Chun / Los Angeles Times)

“We grew up in a radical political tradition of theater, where this is where we can rehearse emotional experience — catharsis,” Blenkarn says. “That is what art is supposed to be doing. We have been very interested in the idea that if we come together, what are we going to do and how are we going to do it? What we are seeing in your country, and other countries, is the question of how are we going to change our behavior, and will the people who currently have the controller listen? And if they don’t, what do we do?”

Video games are inherently theatrical. Even if one is playing solo on the couch, a video game is a dialogue, a performance between a player and unseen designers. Blenkarn and Lim also spoke in an interview prior to the show of wanting to re-create the sensation of gathering around a television and passing a controller back and forth among family or friends while offering commentary on someone’s play style. Only at scale. And while I thought “asses.masses” could work, too, as a solitary experience at home, its themes of collective action and reaching a group consensus, often through boos or shouts of encouragement, made it particularly well-suited for a performance.

The UCLA Nimoy Theater played host to “asses.masses” this weekend.

(Myung J. Chun / Los Angeles Times)

Beginning at 1 p.m. and ending shortly after 8 p.m., coincidentally, says Blenkarn, the length or so of a working day, not everyone made it to the “asses.masses” conclusion. About a quarter of the audience — a crowd that was clearly familiar with the multiple video game style represented in “asses.masses” — couldn’t stand the endurance test. But in a time of binge-watching, I didn’t find the length prohibitive. There were multiple intermissions, but those became part of the show as well, as there was no set time limit. Blenkarn and Lim were asking the audience, via a prompt on the screen, to jointly agree upon a length, emphasizing, once again, the importance of collective cooperation.

And “asses.masses” holds interest because it, in part, embraces the animated absurdity and inherent experimentation of the medium. While often in a retro pixel art style, at times the game shifted into a more modern open-world look. And the story veers down multiple paths and side-quests — some requiring wild coordination such as a rhythm game meant to simulate donkey sex, and others more tense, such as “Metal Gear”-like sneaking, complete with the donkeys hiding in cardboard boxes.

Audiences vote, often by cheering or booing, on choices in “asses.masses.”

(Myung J. Chun / Los Angeles Times)

The way “asses.masses” shifted tones and tenor recalled a game such as “Kentucky Route Zero,” another serialized and alternately realistic and fanciful game with political overtones. Other times, such as the surreal world of the donkey afterlife, I thought of the colorfully unpredictable universe of the music-focused game “The Artful Escape,” a quest for personal identity and self-actualization. The donkeys in “asses.masses” are an ensemble, often trying to steer the audience in different directions. As much as some push for a protest as a way for communal healing and progressive action, others take a cynical outlook, viewing that path as “intellectually compromised” by a “commitment to past ideals.”

The goal, says Lim, is to create a sort of game within a game — one that’s being played with a controller and one of debate among a crowd. “It’s not about having a billion endings,” Lim says. “We understand it’s a theater show, and we as writers have objectives for what we want it to go towards. But the decisions people make in the room really matter. The game is half in the room and half on the screen.”

The audience, for instance, can play a role in keeping certain donkeys alive. Or what jobs a group of renegade donkeys may choose. Our audience voted for the donkeys to enter the circus, at least until they were deemed obsolete and sent to detention centers, which felt uncomfortably of the moment. Such topicality is what drew Edgar Miramontes, leader of CAP UCLA, to the show, despite his admittance to being largely unfamiliar with the world of video games.

“It doesn’t shy away from the nuances of when organizing happens and what we’re seeing in our world right now,” Miramontes says. “There are instances in which a donkey may die because, in organizing to achieve their goals, these things happen. We have seen this in our Civil Rights Movement and other movements and the current movement that’s happening right now around ICE.”

The Nimoy event, part of UCLA’s current Center for the Art of Performance season, was the 50th time “asses.masses” had been performed. The show will continue to tour, with a performance in Boston set for this upcoming weekend and it will reach Chicago later this year. Our donkeys on Saturday didn’t solve all the world’s inequalities, but they did live full lives, attending raves, engaging in casual sex and even playing video games.

A player celebrates during “asses.masses,” live action theatrical video game.

(Myung J. Chun / Los Angeles Times)

The show is an argument that progress isn’t always linear, but community is constant. As one of the donkeys says at one point, “If you aren’t doing something that brings you joy, do something different.”

“In case anyone is like, ‘I don’t want to be lectured at,’ or I don’t want to do all this work, it feels like you’re just having fun with friends,” Lim says. “Maybe revolution doesn’t always look like just this. Maybe it’s also this.”

And like many a video game, maybe it’s a chance to live out some fantasies. “We do beat up riot cops in the game,” Blenkarn says, “in case anyone is hoping for that opportunity.”

Lifestyle

‘E-bike for your feet’: How bionic sneakers could change human mobility

Chloe Veltman evaluates Nike’s Project Amplify system on a steep incline at the LeBron James Innovation Center in Beaverton, Ore., on Jan. 14. She says that after “getting over the surprise” of initially wearing the Project Amplify shoes, “it kind of feels like my feet are being pushed more aggressively forward.”

Gritchelle Fallesgon for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Gritchelle Fallesgon for NPR

The buildings at Nike’s world headquarters — the Philip H. Knight Campus in Beaverton, Ore. — are named after the likes of Serena Williams, Jerry Rice and Mia Hamm. But the company doesn’t recognize only sports superstars as athletes.

“If you have a body, you’re an athlete,” said Mike Yonker, who heads up the team developing Project Amplify — Nike’s new bionic sneaker.

Accordingly, the Project Amplify footwear system is aimed at a broad audience. “Amplify is designed for that everyday athlete to give them the energy they need to go further, to go faster, with greater levels of confidence,” said Yonker. “It’s like an e-bike for your feet.”

Even as some elite athletes are strapping skis and skates to their feet in an effort to move ever faster at this year’s Winter Olympics in Italy, Nike and other companies in the footwear and mobility sectors are on a quest to help humans move farther and faster in everyday life — using digital technology.

Nike said it plans to launch Project Amplify commercially in 2028. The system, tested in prototype form by NPR at the company’s headquarters, consists of fairly standard-looking sneakers with a carbon fiber plate running through the soles. These sneakers are attached at the back to close-fitting, 3D-printed titanium leg shells that cinch to the calves. The battery-powered contraptions, containing complex motors, sensors and circuitry, weigh a couple of pounds and look like something out of Terminator or RoboCop.

Nike’s Project Amplify prototypes are displayed from earliest to latest at the Nike Sport Research Lab in Beaverton, Ore., on Jan. 13.

Gritchelle Fallesgon for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Gritchelle Fallesgon for NPR

The latest iteration of Nike’s Project Amplify at the Nike Sport Research Lab.

Gritchelle Fallesgon for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Gritchelle Fallesgon for NPR

“What it’s doing is learning how your ankles are moving, how long your steps are, taking the algorithms and customizing them for you,” said Alison Sheets-Singer, Project Amplify’s lead scientist. “So that when it turns on, it feels natural and smooth.”

A phone app powers the footwear system on and off and can be used to toggle between various speed settings in “walk” and “run” mode. When activated, the leg shells pick up the heels and propel the feet purposefully forward.

A long quest for speed

Human beings have an innate desire to move faster on foot, whether for practical reasons or thrills and pleasure, said Elizabeth Semmelhack, director and senior curator of the Bata Shoe Museum in Toronto.

“The Nike Amplify comes from this long legacy of trying to increase speed and use science to help us get there,” Semmelhack said.

Semmelhack points to ice skates made of bone from the 1600s, 19th-century in-line roller skates and an iconoclastic pair of crescent-shaped, metal rocking-shoes patented in the early 20th century.

A 1600s bone skate, 19th-century in-line roller skates and a drawing of a patent for metal rocking-shoes from the early 20th century.

Bata Shoe Museum

hide caption

toggle caption

Bata Shoe Museum

Athletic-shoe manufacturers initially worked to increase the wearer’s speed in the 1970s by using lighter materials — switching out rubber and leather for nylon and foam. Electronics started appearing in sneakers in the 1980s. The Adidas Micropacer and Puma RS-Computer shoe used sensors to track a runner’s distance. Nike even came out with self-lacing high-tops a decade ago — the Nike Air Mag. The limited-edition product brought to life the futuristic sneakers featured in the 1989 movie Back to the Future Part II.

YouTube

But none of these innovations used digital technology to increase velocity, because of power constraints. “The energy needed to propel a human being forward is so significant that we do not have an energy source yet that is small enough that can be placed within a shoe,” Semmelhack said.

That’s why Nike and others working on electronic-assisted running and walking systems today, such as the Massachusetts-based startup Dephy — which collaborated with Nike on Project Amplify and also recently launched its own similar product, Sidekick — include ergonomic leg shells to power their products. Some of these systems avoid shoes entirely; for instance, the Ascentiz H+K takes the form of a motorized knee and hip exoskeleton. (According to Nike, Project Amplify is designed to have enough battery life, roughly, to enable the wearer to complete a 10-kilometer run. The batteries are rechargeable and can be switched out for a fresh set if the wearer wants to go for longer.)

Expanding mobility horizons

Despite the power challenges, the electronic-powered, motorized footwear space is a busy one. More than a dozen startups were exhibiting their innovations in the “bionic, footwear, exoskeleton” category at this year’s Consumer Electronics Show (CES) in Las Vegas, one of the world’s most prominent annual showcases for tech innovation. Many of these products are focused on helping people solve mobility issues, rather than necessarily aiding those who already walk and run with ease to do so faster.

“We’ve described a phenomenon called ‘personal range anxiety,’ where people are now making decisions about which activities they opt in and out of based on asking themselves, ‘Will I be comfortable? Will I be in pain? Will I be able to keep up with my friends and family?’” said Dephy co-founder and CEO Luke Mooney. “And so we’re helping them restore that confidence.”

Chloe Veltman walks outside wearing the Nike Amplify system at the Nike campus in Beaverton, Oregon.

Gritchelle Fallesgon for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Gritchelle Fallesgon for NPR

Some experts see a future where these footwear systems make a similar impact on walking and running as electronic bikes have made in recent years on mountain biking.

“E-bikes have changed the landscape of mountain biking for people that maybe didn’t have the ability or were getting older and still wanted to participate,” said Mark Oleson, a former Adidas executive who has worked on many innovation projects in the athletic shoe sector and who currently heads up the women’s volleyball footwear and apparel company Avoli. “There’s a huge opportunity where companies are asking, ‘How do we get someone into a sport or into a recreational activity that they normally wouldn’t have the ability to do?’”

-

Politics5 days ago

Politics5 days agoWhite House says murder rate plummeted to lowest level since 1900 under Trump administration

-

Indiana1 week ago

Indiana1 week ago13-year-old rider dies following incident at northwest Indiana BMX park

-

Indiana1 week ago

Indiana1 week ago13-year-old boy dies in BMX accident, officials, Steel Wheels BMX says

-

Alabama4 days ago

Alabama4 days agoGeneva’s Kiera Howell, 16, auditions for ‘American Idol’ season 24

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoTrump unveils new rendering of sprawling White House ballroom project

-

San Francisco, CA7 days ago

San Francisco, CA7 days agoExclusive | Super Bowl 2026: Guide to the hottest events, concerts and parties happening in San Francisco

-

Culture1 week ago

Culture1 week agoTry This Quiz on Mysteries Set in American Small Towns

-

Massachusetts1 week ago

Massachusetts1 week agoTV star fisherman’s tragic final call with pal hours before vessel carrying his entire crew sinks off Massachusetts coast