Lifestyle

These older women may be 'heading for the coffin,' but they're getting laughs in L.A.

Susan Ware spends each morning, from around 8:30 to 11:30 a.m., crafting jokes.

“I’ve got notebooks. I’ve got sides of the newspaper where I’ve written in the margins. I’ve got jokes written everywhere,” the 80-year-old said. As she thumbs through legal sheets, throwing out old stuff that’s not funny anymore, her two cats and dog lounge lazily on the couch beside her.

Stand-up comedian Susan Ware, 80, favors dark one- and two-liner jokes.

(Juliana Yamada / Los Angeles Times)

“I take too much time working on jokes,” Ware said, calling her daily practice the hardest thing she’s ever done in her life. “It annoys me because I have other things I would like to do.”

A retired real estate agent, Ware started stand-up at 67, when she realized she didn’t want to die with regrets; she had always wanted to try comedy. At a recent open mic, with a close group of comedian friends, she tried out a bit of new material: “My six-year-old nephew fell down the stairs. Now he’s afraid to go down stairs … if I’m standing behind him.”

“I go to the edge, I will tell you,” Ware said of her dark one- and two-liners. “But people laugh.”

-

Share via

Older women might not be what come to mind when thinking of comedians. The misconception that women, and certainly older women, have little to contribute to the comedy sphere drives the undercurrent of Max’s popular comedy-drama “Hacks,” which premiered its fourth season on Thursday.

In the show, Jean Smart plays Deborah Vance, a legendary stand-up trying to reclaim her mojo in the face of bookers who think she won’t appeal to younger audiences. (This season Vance tries her luck as a late-night talk show host.) But as audiences learn, Vance is much more than meets the eye.

It’s a story that rings true for several L.A.-based women who began stand-up comedy at a mature age. Speaking to The Times, these women addressed the lingering misogyny and ageism in the stand-up comedy industry, but said comedy offered them an outlet for self-discovery at an age where women can become invisible. The pay off — of drafting jokes, reworking material and performing at open mics and shows — is the thrill of the applause, but even more so, the emotional freedom it affords them.

For the past 22 years, Mary Huth’s life happily revolved around her twin sons. Changing poopy diapers seamlessly transformed into packing snacks for club sports in high school until suddenly, it seemed, they left home for college. On a whim and to fill the void, Huth signed up for a stand-up comedy class.

“It’s kind of like gambling,” the 61-year-old said of her instant addiction to the craft. “They say you hit the jackpot the first time, and then you’re a compulsive gambler after that.”

It’s easy to get “dumped in the deep end” in a city like Los Angeles, which literally has $5 open mics “all day, every day, seven days a week,” said Patricia Resnick, a screenwriter and producer, who said her mom’s death “made [her] want to try things and live life more.”

Patricia Resnick, 72, penned the movie script “9 to 5” before she started stand-up later in life.

(Juliana Yamada / Los Angeles Times)

Resnick, 72, sees her age as a double-edged sword when it comes to comedy. On one hand, comedy remains a very masculine space, with several women interviewed for this story saying bookers are hesitant to promote older women regardless of their success with audiences.

On the other hand, Resnick, who recently booked the main stage at Flappers Comedy Club in Burbank, says her age and experience inherently offers her a unique perspective when it comes to entertaining audiences.

“People like to be surprised in certain ways,” she said. “So when I talk about being a gay, sober, single mom of two kids by donor insemination, I usually introduce it by saying, ‘You know, I want to talk about something very universal that everybody can relate to.’ And of course, everybody laughs because it’s not what they were expecting.”

Huth’s sons and her wife come up in her comedy. One of her jokes centers around her and her wife’s arduous IVF journey. It’s a bit Huth calls “cathartic” and humanizing for LGBTQ+ parents, especially in today’s political climate.

But beyond parenting challenges, she doesn’t lean into her age in her material.

Comedian Mary Huth, 61, started stand-up after her kids went to college.

(Juliana Yamada / Los Angeles Times)

“I am not interested in doing menopause and Chico’s jokes,” she said. Instead, she critically analyzes the work of younger comics she admires: “Why are they doing it this way? Why is their body moving like this? What are they doing with their timing?”

That strategic thinking, she said, coupled with her ability to not work a full-time job, has paid off. (Many women interviewed for this story said their age gives them the benefit of financial security that younger comics are more likely to lack.) Huth recently booked the Asian Comedy Fest in New York and the Boulder Comedy Festival in Colorado. She also, gleefully, has more Instagram followers than her sons.

“If you would have told me when my kids were seniors in high school that I would be doing this, I would be like, ‘What kind of mushrooms are you on?’” Huth said.

Where other hobbies may be difficult to pick up in middle age, comedy, with its low entrance fee and ubiquitous nature, is an inherently accessible art form.

“Comedy is such a great way for an average person to have a platform and to stand on a stage and use their voice,” said Bobbie Oliver, owner of Tao Comedy Studio, which she said hosts the longest-running all-women’s mic in Los Angeles. “With older women who never had that opportunity in their lives because it just wasn’t really allowed, it’s kind of a freedom for them.”

Tao Comedy Studio owner Bobbie Oliver, 56, hosts a yearly Punk Rock Intersectional Feminist Comedy Festival in June.

(Juliana Yamada / Los Angeles Times)

For the record:

12:36 p.m. April 14, 2025A previous version of this story said Bobbie Oliver was the co-owner of Tao Comedy Studio. She is the owner.

Adine Porino found this freedom close to home when a flyer advertising an open mic in her apartment complex, Park La Brea, stopped her in her tracks: “Stand Up Comedy Open Mic Night Every Sunday 6:30 p.m.”

Considered the funny one among her friends, Porino had wanted to try comedy for over a decade, but was always too scared.

“I just thought, well, I’d check it out,” the 67-year-old said.

The host of the mic, Sabine Pfund, was an up-and-coming comedian from Lebanon; most of the attendees were young male comics familiar with the L.A. comic circuit. Porino left the room inspired.

Adine Porino, 67, regularly attends the Park La Brea Sunday night open mic.

(Juliana Yamada / Los Angeles Times)

“For one week, I just started writing down jokes,” she said. “I tested them out on my friends, and by the end of the week, I had five minutes and I had word-for-word how I wanted the joke to come off … Then I stood there with the mic in front of me, and I literally read [off] my phone.”

Since then, Porino has become a regular at Pfund’s mic and keeps a running list of funny thoughts on her phone. Her signature joke is about how she is a tax preparer and how she once was a caregiver of two elderly women who have died. “So, I don’t recommend my services,” she said, deadpanning.

Stand-up comedian Adine Porino displays her notes app list of jokes on her phone.

(Juliana Yamada / Los Angeles Times)

The energy is refreshing in a different way for Elle McGovern, a 62-year-old restaurant manager who came to comedy after pursuing an acting career. Compared to acting, McGovern found that in comedy “you don’t have to be pretty. You don’t have to be young. You don’t have to be thin. You don’t have to be anything. You just have to be funny.”

McGovern, a regular face at Tao Comedy Studio, describes comedy classes as a workout, but instead of making gains, she’s healing childhood wounds.

For example, in one of her jokes, she teases herself for once drawing one of her eyebrows on way too high. The joke begins with poking fun at how she constantly looked inquisitive. But after working the joke over time, McGovern was able to connect her missing eyebrow to a childhood hurt: “It went out for a smoke and never came back, just like my dad.”

“Just saying out loud some of the things that were hurtful about childhood, the pain goes away and you realize everybody has stuff,” she said.

Mary Pease, 75, started stand-up after a period of feeling “lost.”

(Juliana Yamada / Los Angeles Times)

Mary Pease, who refers to herself as a “vintage classic,” found a similar release through comedy. At the time, she was grappling with the dissolution of her 35-year marriage.

“I was really confused about life,” the 75-year-old said. “Where do I go now? I’ve already had the marriage. I’ve already had the children. I already had a good career.”

It was her adult son who suggested Pease go to a comedy club because she had always liked comedians. Pease got $5 tickets to a show at the Nitecap, a comedy club in Burbank, where she was introduced to Genesis Sol, a young comedian who, at the time, was running her all-women’s mic Witty Titties at the club.

“That changed my life,” said Pease, who was invigorated by the excitement and hope of the young comics around her. Since then, Sol said she’s become the oldest regular at Witty Titties. In her signature storytelling style, Pease relays tragically funny memories about her childhood in rural Arkansas.

“Going to [Witty Titties] totally made me stop using the words ‘I’m divorced.’ I’m retired. It was a good game. I got four Super Bowl rings,” she said referring to her four children. “We still celebrated.”

Stand-up comedians Mary Pease, left, Mary Huth and Patricia Resnick.

(Juliana Yamada / Los Angeles Times)

Laughing at herself has helped McGovern feel more secure during a time of her life when she said society would otherwise render her “obsolete.”

“I love having people laugh at me. That’s a great feeling,” McGovern said. “But I think, for me, it’s more the journey of it, the spirituality of it.”

“It’s giving me a new lease on life, because it gives me something that I love to do, that expresses my creativity and my art, and I can be fulfilled without having a financial reward from it,” she said.

Ware, the 80-year-old comic who writes jokes daily, said she would have been interested in a comedy career if she were younger, but she accepts the reality of her situation.

“I’m headed for the coffin. I’m not headed for the big stage,” she said.

Regardless, every morning Ware can be found on her couch next to her cats and dog as she comes up with her next punchline.

“I quit comedy every day,” she said. “Ah, I’m not going to do this. It’s too hard. I’m tired of thinking of jokes. And all I have to do is think of one joke, and I’m back in.”

Susan Ware, left, has been performing for more than 10 years, while Adine Porino started stand-up just five months ago.

(Juliana Yamada / Los Angeles Times)

Lifestyle

In Brooklyn’s Park Slope neighborhood, children’s entertainment comes with strings

The Tin Soldier, one of Nicolas Coppola’s marionette puppets, is the main character in The Steadfast Tin Soldier show at Coppola’s Puppetworks theater in Brooklyn’s Park Slope neighborhood.

Anh Nguyen for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Anh Nguyen for NPR

Every weekend, at 12:30 or 2:30 p.m., children gather on foam mats and colored blocks to watch wooden renditions of The Tortoise and the Hare, Pinocchio and Aladdin for exactly 45 minutes — the length of one side of a cassette tape. “This isn’t a screen! It’s for reals happenin’ back there!” Alyssa Parkhurst, a 24-year-old puppeteer, says before each show. For most of the theater’s patrons, this is their first experience with live entertainment.

Puppetworks has served Brooklyn’s Park Slope neighborhood for over 30 years. Many of its current regulars are the grandchildren of early patrons of the theater. Its founder and artistic director, 90-year-old Nicolas Coppola, has been a professional puppeteer since 1954.

The Puppetworks theater in Brooklyn’s Park Slope neighborhood.

Anh Nguyen for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Anh Nguyen for NPR

A workshop station behind the stage at Puppetworks, where puppets are stored and repaired.

Anh Nguyen for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Anh Nguyen for NPR

A picture of Nicolas Coppola, Puppetworks’ founder and artistic director, from 1970, in which he’s demonstrating an ice skater marionette puppet.

Anh Nguyen for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Anh Nguyen for NPR

For just $11 a seat ($12 for adults), puppets of all types — marionette, swing, hand and rod — take turns transporting patrons back to the ’80s, when most of Puppetworks’ puppets were made and the audio tracks were taped. Century-old stories are brought back to life. Some even with a modern twist.

Since Coppola started the theater, changes have been made to the theater’s repertoire of shows to better meet the cultural moment. The biggest change was the characterization of princesses in the ’60s and ’70s, Coppola says: “Now, we’re a little more enlightened.”

Right: Michael Jones, Puppetworks’ newest puppeteer, poses for a photo with Jack-a-Napes, one of the main characters in The Steadfast Tin Soldier. Left: A demonstration marionette puppet, used for showing children how movement and control works.

Anh Nguyen for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Anh Nguyen for NPR

Marionette puppets from previous Puppetworks shows hang on one of the theater’s walls.

Anh Nguyen for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Anh Nguyen for NPR

A child attends Puppetworks’ 12:30 p.m. showing on Saturday, Dec. 6, dressed in holiday attire that features the ballerina and tin soldier in The Steadfast Tin Soldier.

Anh Nguyen for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Anh Nguyen for NPR

Streaming has also influenced the theater’s selection of shows. Puppetworks recently brought back Rumpelstiltskin after the tale was repopularized following Dreamworks’ release of the Shrek film franchise.

Most of the parents in attendance find out about the theater through word of mouth or school visits, where Puppetworks’ team puts on shows throughout the week. Many say they take an interest in the establishment for its ability to peel their children away from screens.

Whitney Sprayberry was introduced to Puppetworks by her husband, who grew up in the neighborhood. “My husband and I are both artists, so we much prefer live entertainment. We allow screens, but are mindful of what we’re watching and how often.”

Left: Puppetworks’ current manager of stage operations, Jamie Moore, who joined the team in the early 2000s as a puppeteer, holds an otter hand puppet from their holiday show. Right: A Pinocchio mask hangs behind the ticket booth at Puppetworks’ entrance.

Anh Nguyen for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Anh Nguyen for NPR

A child attends Puppetworks’ 12:30 p.m. showing on Saturday, Dec. 6, dressed in holiday attire.

Anh Nguyen for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Anh Nguyen for NPR

Left: Two gingerbread people, characters in one of Puppetworks’ holiday skits. Right: Ronny Wasserstrom, a swing puppeteer and one of Puppetworks’ first puppeteers, holds a “talking head” puppet he made, wearing matching shirts.

Anh Nguyen for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Anh Nguyen for NPR

Other parents in the audience say they found the theater through one of Ronny Wasserstrom’s shows. Wasserstrom, one of Puppetworks’ first puppeteers, regularly performs for free at a nearby park.

Coppola says he isn’t a Luddite — he’s fascinated by animation’s endless possibilities, but cautions of how it could limit a child’s imagination. “The part of theater they’re not getting by being on the phone is the sense of community. In our small way, we’re keeping that going.”

Puppetworks’ 12:30 p.m. showing of The Steadfast Tin Soldier and The Nutcracker Sweets on Saturday, Dec. 6.

Anh Nguyen for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Anh Nguyen for NPR

Children get a chance to see one of the puppets in The Steadfast Tin Soldier up close after a show.

Anh Nguyen for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Anh Nguyen for NPR

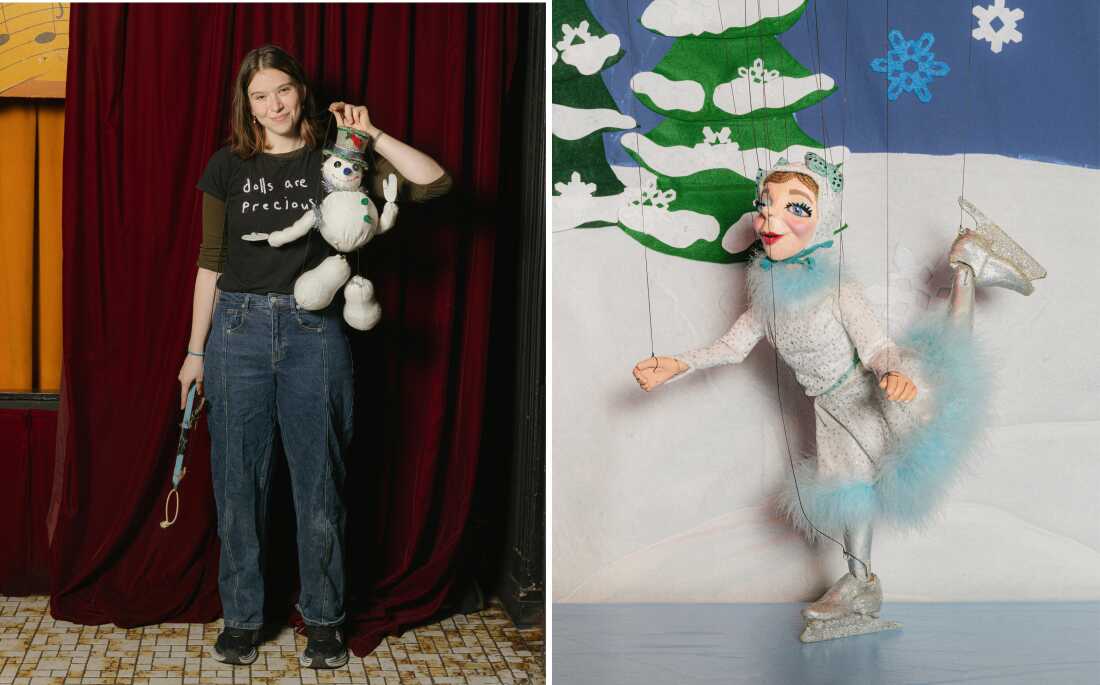

Left: Alyssa Parkhurst, Puppetworks’ youngest puppeteer, holds a snowman marionette puppet, a character in the theater’s holiday show. Right: An ice skater, a dancing character in one of Puppetworks’ holiday skits.

Anh Nguyen for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Anh Nguyen for NPR

Community is what keeps Sabrina Chap, the mother of 4-year-old Vida, a regular at Puppetworks. Every couple of weeks, when Puppetworks puts on a new show, she rallies a large group to attend. “It’s a way I connect all the parents in the neighborhood whose kids go to different schools,” she said. “A lot of these kids live within a block of each other.”

Three candy canes — dancing characters in one of Puppetworks’ holiday skits — wait to be repaired after a show.

Anh Nguyen for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Anh Nguyen for NPR

Anh Nguyen is a photographer based in Brooklyn, N.Y. You can see more of her work online, at nguyenminhanh.com , or on Instagram, at @minhanhnguyenn. Tiffany Ng is a tech and culture writer. Find more of her work on her website, breakfastatmyhouse.com.

Lifestyle

The Best of BoF 2025: Fashion’s Year of Designer Revamps

Lifestyle

Best Christmas gift I ever received : Pop Culture Happy Hour

-

Iowa1 week ago

Iowa1 week agoAddy Brown motivated to step up in Audi Crooks’ absence vs. UNI

-

Maine1 week ago

Maine1 week agoElementary-aged student killed in school bus crash in southern Maine

-

Maryland1 week ago

Maryland1 week agoFrigid temperatures to start the week in Maryland

-

New Mexico1 week ago

New Mexico1 week agoFamily clarifies why they believe missing New Mexico man is dead

-

South Dakota1 week ago

South Dakota1 week agoNature: Snow in South Dakota

-

Detroit, MI1 week ago

Detroit, MI1 week ago‘Love being a pedo’: Metro Detroit doctor, attorney, therapist accused in web of child porn chats

-

Health1 week ago

Health1 week ago‘Aggressive’ new flu variant sweeps globe as doctors warn of severe symptoms

-

Massachusetts1 week ago

Massachusetts1 week agoMIT professor Nuno F.G. Loureiro, a 47-year-old physicist and fusion scientist, shot and killed in his home in Brookline, Mass. | Fortune