Lifestyle

Smokey Bear turns 80 this year. Did he help prevent forest fires?

Smokey the bear cub is flown from Santa Fe, N.M., to his new home at the Washington National Zoo in a Piper J-3 Cub by New Mexico Assistant State Game Warden Homer C. Pickens in 1950. The little bear was rescued from a forest fire and named Smokey after the fire prevention symbol of the U.S. Forest Service.

FPG/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

FPG/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

The longest-running public service announcement in the U.S. turns 80 years old today.

Its message is simple and one you’ve heard many times before: “Only you can prevent wildfires.” Smokey Bear, the beloved park ranger hat-wearing black bear who utters these famous words has undergone a complicated evolution.

And his birthday comes as fires rage in California, Colorado and other Western states. On average, some 70,000 wildfires have been documented every year in the U.S. since 1983, according to data from the National Interagency Fire Center.

Human-caused climate change has made these fires more intense and dangerous, but it isn’t the only factor: Federal data and various independent studies show that around 80% of all wildfires in the country are caused by humans, making Smokey’s message more relevant than ever.

So we’re taking a look back at how Smokey Bear’s mission came to be and how effective his messaging has been.

How World War II influenced Smokey Bear’s creation

Fire burns near a Smokey the Bear fire warning sign as the Oak Fire burns through the area on July 24, 2022 near Jerseydale, California.

Justin Sullivan/Getty Images/Getty Images North America

hide caption

toggle caption

Justin Sullivan/Getty Images/Getty Images North America

Smokey Bear’s public service ad was created at the height of World War II in 1944. The U.S. Forest Service had been fighting forest fires for years, but the attack on Pearl Harbor brought a greater need for fire safety messaging, as firefighters were deployed overseas.

“When this campaign first launched, it was in the context of our war efforts, and the forests were seen as a resource in that context,” said Tracy Danicich, director of the Smokey Bear campaign at the Ad Council.

A few weeks after the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, a Japanese submarine sitting off the coast fired shells at an oil facility in Santa Barbara County, Calif. south of the Los Padres National Forest. The attack raised fears that more attacks like this could cause wildfires in forests along the Pacific coast. The Forest Service hoped that connecting the risk of fires to the war effort would help make the case for fighting forest fires more urgent.

“There was also a rise in wildfires just from general human carelessness, lack of respect for fire, perhaps lack of knowledge of how to contain and properly respect a fire,” said Tad Bennicoff, a reference archivist at the Smithsonian Institution archives. “So the Forest Service came up with the idea of the Smokey Bear character and the message.”

But even after World War II ended, Smokey stuck around. He started showing up on posters, U.S. Postal Service stamps, in radio ads and alongside stars like Bing Crosby and Ward Bond.

You might remember calling the forest fire fighting black bear “Smokey the Bear,” but that isn’t actually his name.

In 1952, singers Steve Nelson and Jack Rollins wrote a jingle for and added a “the” to maintain the song’s rhythm. This inadvertently created confusion about the bear’s name, but the U.S. Forest Service maintains that Smokey’s official name is “Smokey Bear,” not “Smokey the Bear.”

The campaign’s mascot was an actual bear rescued from a wildfire

The Smokey Bear balloon floats in the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade on Thursday, Nov. 25, 2021, in New York. (Photo by Charles Sykes/Invision/AP)

Charles Sykes/Charles Sykes/Invision/AP/Invision

hide caption

toggle caption

Charles Sykes/Charles Sykes/Invision/AP/Invision

In the spring of 1950, a group of Native American firefighters rescued a bear cub who clung to a tree as a fire raged in the Capitan Mountains in New Mexico.

After its rescue, the cub became the symbol of the Smokey Bear campaign and was put on display at the National Zoo in Washington, D.C.

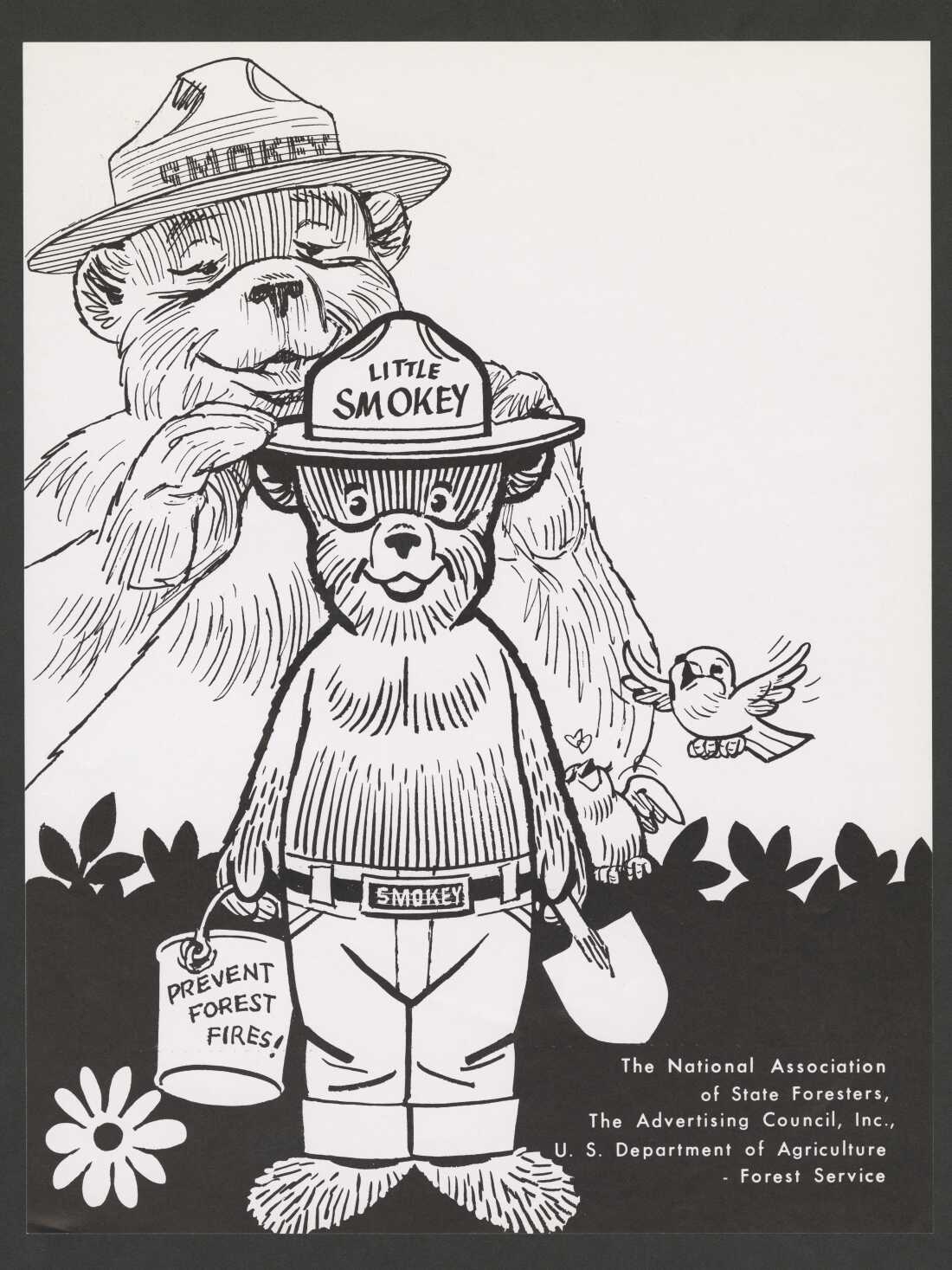

But the physical public service announcements, which for years showed a black bear in a pair of blue pants, a tan wide-brimmed park ranger’s hat and a metal shovel, confused some zoo goers.

Bennicoff said this outfit was so closely associated with Smokey that some young kids were bewildered when they saw a naked bear at the National Zoo.

Visitors were startled to see a real bear, Bennicoff said. “They were expecting to see the Smokey Bear that they saw in print ads and on television. But lo and behold, there’s this actual bear.”

Forest Service cartoon of Smokey Bear welcoming Little Smokey./Smithsonian Institution Archives

To help with the confusion, the zoo added a special exhibit next to Smokey’s enclosure that featured a park ranger’s uniform in Smokey’s size. During this time, Smokey Bear was receiving so much fan mail that the Zoo had to hire three assistants to keep up with the amount of letters he was getting. He even got his own ZIP code — an honor only bestowed to one other figure: the president.

Smokey retired from the zoo at 25. In human years, he would have been roughly 70, the mandatory retirement age for federal employees at the time. In 1971, the zoo introduced “Little Smokey,” another orphan cub rescued by the Forest Service. When Smokey retired, Little Smokey took over the mantle.

The original Smokey died Nov. 9,1976, a year after his retirement. His remains were returned to New Mexico, where he was buried in the Smokey Bear Historical Park in Capitan, N.M., not far from where he was rescued two decades prior.

A small change for Smokey represents a big change for environmentalism

Wild mustard flowers bloom around a Smokey Bear sign in Griffith Park in Los Angeles, Thursday, June 8, 2023.

Jae C. Hong/AP/AP

hide caption

toggle caption

Jae C. Hong/AP/AP

For five decades, Smokey’s slogan remained the same: “Only you can prevent forest fires.” The message suggested that all fires were preventable and bad for the environment and that nature could return to its original state if fires didn’t occur.

In one ad, Smokey said that if people just took his message into their hearts, it could be like “the old times, maybe, when great herds of buffalo roamed.“

Melinda Adams, an Indigenous fire scientist and assistant professor in the Department of Geography and Atmospheric Science at the University of Kansas told Morning Edition that Smokey’s vision of an America without wildfires isn’t accurate.

“When you had colonizers come over and look at land, mosaics or beautiful landscapes, they developed a narrative of [these] being untouched by humans, virgin lands. They arrived and the lands were like that,” Adams said. “But we know through the recent scholarship that that’s not true. We know that Indigenous peoples created these landscapes or maintained them.”

Adams is a proponent of what she calls good fire — or burns to land that help an environment thrive. This practice is also called prescribed burning.

This is one of the reasons that in 2001, Smokey Bear changed his slogan from only you can prevent forest fires to only you can prevent wildfires. This change in messaging also represented a change in how the U.S. Forest Service approached fire treatment.

“Now, the U.S. Forest Service and the U.S Department of Agriculture are redirecting resources to good fire, beneficial fire during the off fire season in order to reduce the overgrowth that, you know, decades of fire suppression of fire deficiency has left, which makes those areas of lands more flammable,” Adams said.

The road ahead for Smokey

A Smokey the Bear forest fire prevention sign stands in front of snow blanketing the Sierra Nevada mountains after recent storms increased the snowpack on February 23, 2024 near Bishop, California. (Photo by Mario Tama/Getty Images)

Mario Tama/Getty Images/Getty Images North America

hide caption

toggle caption

Mario Tama/Getty Images/Getty Images North America

Most wildfires are still caused by human activity, which raises the question: Has Smokey’s messaging actually been effective?

John Miller, the chief of Fire and Emergency Response at the Virginia Department of Forestry, said that there is still a lot of work to be done to educate the public on fire safety.

It’s not enough, Miller said, for officials who work in fire prevention education to stand “with [their] arm around Smokey Bear shouting fire prevention on an occasional TV commercial or at a school near you or at a county fair with a booth. Somehow we need to turn that prevention into more to be more front and center to the public.”

Miller believes that one of the big problems is that people are not aware of smaller fires that occur in areas like Virginia all the time.

“Thankfully, because of quick and efficient suppression those fire hours are suppressed quickly. They don’t become newsworthy,” Miller said. “If it hadn’t impacted a home or damaged the public just never hears about that.”

Miller thinks these smaller fires can be prevented, especially because they are often caused by humans who are not aware of simple ways they can be practicing fire safety.

Which is exactly what Smokey Bear’s evolving message is — the best way to continue to spread awareness about safe fires.

“His tips evolve, and there are other things about Smokey and the campaign that have evolved to stay relevant, but that message and focus has always remained consistent,” Danicich said.

This digital story was edited by Obed Manuel.

Lifestyle

Internal memo details cosmetic changes and facility repairs to Kennedy Center

A person walks a dog in front of the Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C., on Jan. 10, 2026.

Mandel Ngan/AFP via Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Mandel Ngan/AFP via Getty Images

An internal email obtained by NPR details some of the projected refurbishments planned for the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts. The renovations are more modest in scale and scope than what President Trump has publicly outlined for the revamped arts center, and it is unclear whether or not these plans are the extent of the intended renovations.

The email was sent on Feb. 2 by Brooks Boeke, the director of the Friends of the Kennedy Center volunteer program, to tour leaders and some staffers at the arts complex. In a response to NPR emailed Tuesday, Roma Daravi, the Kennedy Center’s vice president of public relations, wrote: “The Trump Kennedy Center has been completely transparent about the renovations needed to restore and revitalize the institution, ever since these proposals were unveiled for Congressional approval last summer. The changes that the Center will undergo as part of this intensive beautification and restoration project are critical to saving the building, enhancing the patron experience and transforming America’s cultural center into a world-class destination.”

The center’s closure was announced after many prominent artists canceled their planned appearances, saying that the Trump administration had politicized the arts. The Washington National Opera, which had been a resident organization at the Kennedy Center, left its home there last month, citing a “financially challenging relationship” under the center’s current leadership; The Washington Post, in an analysis of Kennedy Center ticket sales last October, reported that ticket sales had plummeted since Trump became the center’s chairman – even before the complex’s board renamed the venue as the Trump-Kennedy Center in December.

In her memo, Boeke cited Carissa Faroughi, the Kennedy Center’s director of the program management office. Boeke said that upcoming renovations to the complex’s Concert Hall will include replacing seating and installing marble armrests, which President Trump touted on his Truth Social platform in December as “unlike anything ever done or seen before!” Other changes include new carpeting, replacement of the wood flooring on the Concert Hall stage and “strategic painting.”

The planned changes to the Grand Foyer, Hall of States and Hall of Nations include a change of color scheme, from the current red carpeting and seating to “black with a gold pattern.” The carpeting and furnishings in these three areas and its electrical outlets were redone just two years ago, according to the Kennedy Center, and were accomplished without interrupting performances and programming.

Other planned work on the complex include upgrades of the HVAC, safety and electrical systems as well as improving parking. It is unclear whether these plans are the extent of the intended renovations; Daravi declined to answer that specific question.

The scope of the project as outlined in the memo differs sharply from public statements by President Trump, who said earlier this month on social media and in exchanges with the press that he intends a “complete rebuilding” and large-scale changes to the Kennedy Center, and that the arts complex is “dilapidated” and “dangerous” in its current state.

Earlier this month, Trump said that a two-year shutdown of the Kennedy Center is necessary to execute these renovations. This idea was echoed by the center’s president, Richard Grenell. Grenell wrote on X that the Kennedy Center “desperately needs this renovation and temporarily closing the Center just makes sense – it will enable us to better invest our resources, think bigger and make the historic renovations more comprehensive.”

On Feb. 1, Trump announced his plans to close the center entirely for two years “for Construction, Revitalization, and Complete Rebuilding” to create what he said “can be, without question, the finest Performing Arts Facility of its kind, anywhere in the World.” He later said that the project would cost around $200 million. The announcement came after many prominent artists had canceled their existing scheduled appearances at the Kennedy Center.

Lifestyle

South L.A. just became a Black cultural district. So where should its monument stand?

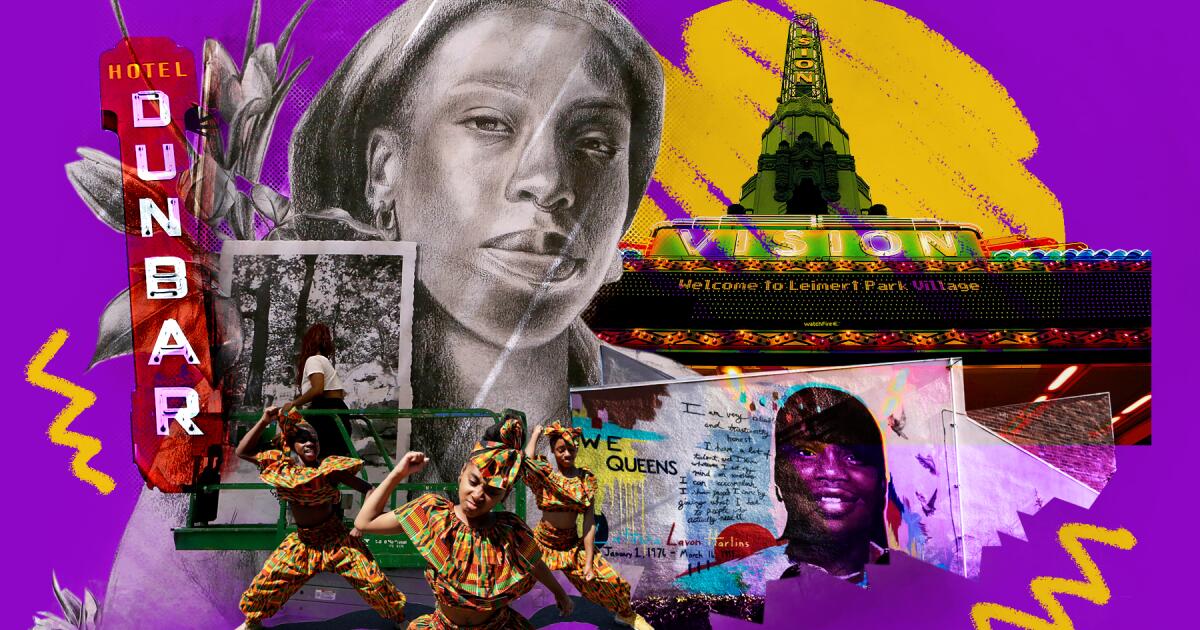

For more than a century, South Los Angeles has been an anchor for Black art, activism and commerce — from the 1920s when Central Avenue was the epicenter of the West Coast jazz scene to recent years as artists and entrepreneurs reinvigorate the area with new developments such as Destination Crenshaw.

Now, the region’s legacy is receiving formal recognition as a Black cultural district, a landmark move that aims to preserve South L.A.’s rich history and stimulate economic growth. State Sen. Lola Smallwood-Cuevas (D-Los Angeles), who led the effort, helped secure $5.5 million in state funding to support the project, and in December the state agency California Arts Council voted unanimously to approve the designation. The district, formally known as the Historic South Los Angeles Black Cultural District, is now one of 24 state-designated cultural districts, which also includes the newly added Black Arts Movement and Business District in Oakland.

Prior to this vote, there were no state designations that recognized the Black community — a realization that made Smallwood-Cuevas jump into action.

“It was very frustrating for me to learn that Black culture was not included,” said Smallwood-Cuevas, who represents South L.A. Other cultural districts include L.A.’s Little Tokyo and San Diego’s Barrio Logan Cultural District, which is rooted in Chicano history. Given all of the economic and cultural contributions that South L.A. has made over the years through events like the Leimert Park and Central Avenue jazz festivals and beloved businesses like Dulan’s on Crenshaw and the Lula Washington Dance Theatre, Smallwood-Cuevas believed the community deserved to be recognized. She worked on this project alongside LA Commons, a nonprofit devoted to community-arts programs.

Beyond mere recognition, Smallwood-Cuevas said the designation serves as “an anti-displacement strategy,” especially as the demographics of South L.A. continue to change.

“Black people have experienced quite a level of erasure in South L.A.,” added Karen Mack, founder and executive director of LA Commons. “A lot of people can’t afford to live in areas that were once populated by us, so to really affirm our history, to affirm that we matter in the story of Los Angeles, I think is important.”

The Historic South L.A. Black Cultural District spans roughly 25 square miles, situated between Adams Boulevard to the north, Manchester Boulevard to the south, Central Avenue to the east and La Brea Avenue to the west.

Now that the designation has been approved, Smallwood-Cuevas and LA Commons have turned their attention to the monument — the physical landmark that will serve as the district’s entrance or focal point — trying to determine whether it should be a gateway, bridge, sculpture or something else.

And then there’s the bigger question: Where should it be placed? After meeting with organizations like the Black Planners of Los Angeles and community leaders, they’ve narrowed their search down to eight potential locations including Exposition Park, Central Avenue and Leimert Park, which received the most votes in a recent public poll that closed earlier this month.

As organizers work to finalize the location for the cultural district’s monument by this summer, we’ve broken down the potential sites and have highlighted their historical relevance. (Please note: Although some of the sites are described as specific intersections, such as Jefferson and Crenshaw boulevards, organizers think of them more as general areas.)

Lifestyle

Urban sketchers find the sublime in the city block

Portland’s Union Station, captured in watercolor and pen by an artist at the Urban Sketchers Portland event.

Deena Prichep

hide caption

toggle caption

Deena Prichep

Great landscape art can take you into a world: the majestic hills of Georgia O’Keeffe’s Southwestern sublime; the pastoral calm of Monet’s water lilies. But for years now, groups of amateurs have been gathering with sketchbooks in cities across the world to turn their artistic gaze to the everyday sights of skyscrapers and sidewalks — and find beauty there.

The idea of “urban sketchers,” or the name at least, started almost 20 years ago. Gabriel Campanario was looking to get to know his new home — and improve his drawing skills.

“We had just moved to Seattle, and I started drawing. Like every day I drew the commuters on the bus, I would draw the mountains, the buildings,” remembered Campanario.

He posted his drawings on the website Flickr and invited other artists to join the online group, which led to in-person groups. And then more chapters, and then international gatherings. Urban Sketchers now reports more than 500 chapters in over 70 countries.

“You can go to another town and meet up with a Sketchers group there,” said Campanario. “And you may not speak the language, but they all can look at your sketchbook and somewhat relate.”

Urban Sketchers Portland was one of the earliest chapters. They meet up monthly. Amy Stewart is one of the organizers.

“We’ll just pick a different neighborhood to explore, where we might be drawing old houses, or little corner markets, or maybe there’s a cool old movie theater to draw,” said Stewart.

Stewart is a writer by profession and says a lot of the sketchers who show up (usually about 50 or so) are similarly amateurs, along with a few more-experienced artists.

Karen Hansen, who discovered Urban Sketchers last year, came prepared with a folding chair and a magnetic watercolor paint palette, so she could pop in the colors she wanted to use for today’s painting.

Deena Prichep

hide caption

toggle caption

Deena Prichep

At a recent meetup at Portland’s Union Station, self-described recovering architect Bob Boileau appreciated that after a career spent drawing straight lines, “It’s nice to just get some squiggly in there and, and put some color and draw how I feel.”

Others, like sketcher Karen Hansen, noted that stopping and really paying attention to a scene helped her see the details that she had taken for granted in everyday life.

“When you’re drawing and painting something, you’re really looking at the shapes and the shadows and the textures,” said Hansen.

At the Portland meetup, sketchers were gathered in little clusters around the train station, capturing its red bricks and tall clock tower with watercolors, or pen and ink, or colored pencils.

It’s arguably not as majestic as most rural landscapes, but Noor Alkurd, drawing at his second Urban Sketchers meetup, said that the boxes and lines of cities are great for beginning artists. And besides, landscapes are overrated.

Urban Sketchers events end with a “throwdown,” where all the artists lay out their sketchbooks and share their work with each other.

Deena Prichep

hide caption

toggle caption

Deena Prichep

“I mean, come on — cityscapes are so fun!” Alkurd said with a laugh. “I think drawing has helped me just see more of everyday life. It kind of helps you train your own eye for what you find beautiful.”

At the end of the sketch session, all of the participants laid their finished art side by side to compare and admire.

There was some shop talk among sketchers about technique and materials, and some recognition of progress for sketchers who had been coming for a while. But mostly, sketchers said it’s just a chance to create a record of a moment, to take in other perspectives, and to notice a little bit more about the city they see every day.

-

Oklahoma2 days ago

Oklahoma2 days agoWildfires rage in Oklahoma as thousands urged to evacuate a small city

-

Health1 week ago

Health1 week agoJames Van Der Beek shared colorectal cancer warning sign months before his death

-

Science1 week ago

Science1 week agoA SoCal beetle that poses as an ant may have answered a key question about evolution

-

Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoHP ZBook Ultra G1a review: a business-class workstation that’s got game

-

![“Redux Redux”: A Mind-Blowing Multiverse Movie That Will Make You Believe in Cinema Again [Review] “Redux Redux”: A Mind-Blowing Multiverse Movie That Will Make You Believe in Cinema Again [Review]](https://i1.wp.com/www.thathashtagshow.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/Redux-Redux-Review.png?w=400&resize=400,240&ssl=1)

![“Redux Redux”: A Mind-Blowing Multiverse Movie That Will Make You Believe in Cinema Again [Review] “Redux Redux”: A Mind-Blowing Multiverse Movie That Will Make You Believe in Cinema Again [Review]](https://i1.wp.com/www.thathashtagshow.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/Redux-Redux-Review.png?w=80&resize=80,80&ssl=1) Movie Reviews1 week ago

Movie Reviews1 week ago“Redux Redux”: A Mind-Blowing Multiverse Movie That Will Make You Believe in Cinema Again [Review]

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoCulver City, a crime haven? Bondi’s jab falls flat with locals

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoTim Walz demands federal government ‘pay for what they broke’ after Homan announces Minnesota drawdown

-

Fitness1 week ago

Fitness1 week ago‘I Keep Myself Very Fit’: Rod Stewart’s Age-Defying Exercise Routine at 81