Politics

From working with Black Panthers to calling for cease-fire, Barbara Lee stands by her beliefs

On a rainy January day, Rep. Barbara Lee wandered the campus of Mills College pointing out sites from her momentous past.

The leafy, seminary-like grounds in Oakland look different from when she attended. To her frustration, even the school’s name has been changed to Northeastern University Oakland.

But for Lee, her time on campus is preserved in amber — the years of student activism, her first trip to Africa, and a political awakening.

Rep. Barbara Lee gives a tour of her alma mater, Northeastern University Oakland. “I’m a Black woman in America; we always have to deal with stuff, because like Shirley Chisholm said, ‘These rules weren’t made for me,’’’ she said.

(Loren Elliott / For The Times)

It’s where she met Shirley Chisholm, the first Black woman elected to Congress, and where she volunteered with the Black Panthers during the tumultuous late 1960s and early ’70s. Her work at the women’s college provided her first taste of Oakland politics, one that carried her to Congress and now animates her bid for the U.S. Senate against fellow Democratic Reps. Adam B. Schiff and Katie Porter, as well as Republican and former Dodger Steve Garvey.

“She is an organic leader who was a seed that came from the soil of the Oakland community, which has long cared deeply about doing right in society,” said retired Pastor Alfred J. Smith, 92, a famed local clergyman who led Allen Temple Baptist Church, which Lee has attended for decades.

Lee’s quarter-century serving in Congress has been defined by that desire to do right. At times it’s been a lonesome pursuit, but it’s one that she feels has, over the years, proved prescient.

Lee cast the sole vote in 2001 against the Authorization for the Use of Military Force that gave then-President George W. Bush the power to wage war against the nations, people and organizations that aided the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks that felled the World Trade Center towers.

Her support in 2003 for Medicare for all, to provide comprehensive healthcare to all Americans, was considered a relatively fringe position at the time but is now a common topic of debate in Democratic primaries.

Lee speaks during a televised debate on Jan. 22 in Los Angeles for candidates in the Senate race to succeed the late Dianne Feinstein.

(Damian Dovarganes / Associated Press)

More recently, Lee, 77, called for a cease-fire the day after Hamas’ Oct. 7 attack on Israel, as Israel’s military began responding with attacks on the Gaza Strip, where Hamas is based. Her top Democratic opponents, Schiff and Porter, both declined to take that position initially. Porter later came to support a cease-fire, while Schiff remains opposed to one.

During her time in Congress, Lee has represented one of the most liberal districts in the state if not the country, which gives her the freedom to stick to her progressive ideals and take tough, sometimes unpopular stands. But that shield also has been isolating, since issues that might be popular in Oakland and Berkeley may not be as closely embraced in less politically progressive areas of the state.

Though much of the nation sees California as a far-left haven, its residents hold a wide range of political views, which may explain in part why Lee has been languishing in recent opinion surveys on the Senate race. The latest polling from the UC Berkeley Institute of Governmental Studies last month indicated that Schiff was backed by 21% of likely voters, compared with 17% for Porter and 13% for Garvey. Lee was in fourth, with the support of 9% of likely voters.

Schiff and Porter also have far larger national profiles and more sophisticated fundraising operations than Lee, said Ludovic Blain, executive director of the progressive California Donor Table, which has endorsed Lee.

From left, Reps. Barbara Lee, Adam B. Schiff and Katie Porter along with Republican Steve Garvey participate in a Senate debate last month in Los Angeles.

(Damian Dovarganes / Associated Press)

“She and those of us who support her haven’t been able to pull together the funds needed to educate voters about her, especially younger voters,” Blain said.

Just nine Black people have ever been elected to the Senate. Only two, Lee is quick to remind people, were women. Now more than ever, she said, the Senate needs her experience — which includes living through America’s civil rights movement and the entrenched discrimination that still lingers more than half a century later; the daily challenges of single motherhood; being surveilled by the FBI as a young activist in Oakland; and facing death threats and accusations of being a traitor for opposing the war in Afghanistan.

“I’m a Black woman in America; we always have to deal with stuff, because like Shirley Chisholm said, ‘These rules weren’t made for me,’” Lee said.

Lee’s assertiveness has made Democratic leaders uncomfortable at times, including last fall when she criticized Gov. Gavin Newsom for saying he’d appoint a Black woman to the seat to replace the late Sen. Dianne Feinstein — but not any of the candidates already running in the 2024 Senate election, since that would provide an advantage. That took Lee out of consideration for an appointment.

“By advocating for herself, she never had a chance. The minute she spoke up she [disqualified] herself,” said Democratic consultant Doug Herman, who helped elect Los Angeles Mayor Karen Bass in 2022.

In the end, Newsom appointed Emily’s List Chief Executive Laphonza Butler, who later announced she wouldn’t run for a full term.

For Blain and other Lee allies, the goal was not to get a Black woman into that seat just to serve until the end of 2024 — but to have one win and serve an entire term.

“She did a great job of pushing, because the knots that Gavin tied himself up in needed to be exposed. He needed to be held accountable,” Blain said of Lee’s criticism of the governor.

::

Lee’s political idealism and moral clarity rose from a life beset by heartache, personal injustice and misfortune.

Born in El Paso, Lee recalls often how her mother, Mildred, nearly died during childbirth. When Lee was a teenager, her family moved to the San Fernando Valley, where she became the first Black cheerleader at her high school after her mother urged her to enlist the support of the local chapter of the NAACP, the civil rights group.

Lee later became pregnant, and since abortion was then illegal in California — as it is now in many conservative states — her mother sent her back to Texas to cross the border with $200 to obtain an abortion in Ciudad Juárez, Mexico.

When she was just out of high school, she married an Air Force serviceman and moved to England, where they lived for two years before divorcing. She landed in the Bay Area with their two sons and began dating a man who abused her, she recounted in her autobiography, “Renegade for Peace and Justice: Congresswoman Barbara Lee Speaks for Me.”

Lee at a civil rights and nuclear disarmament march on the National Mall in Washington in 1978.

(Barbara Lee)

In the aftermath of this trauma, she floated in and out of homelessness — staying in cheap hotels to keep her young boys off the streets.

It was around this time when Lee arrived on Mills College’s campus and became enmeshed in the activist culture of the Black Panthers. By 1971 the organization had become famous — and heavily criticized — for its founders’ view that Black Americans needed to arm and protect themselves from law enforcement agencies targeting Black communities.

In the late 1960s, violent confrontations between the Black Panthers and police across the nation left organization leaders dead. The Black Panther Party’s armed patrols of Oakland neighborhoods to protect residents from police brutality, and their armed protest at the state Capitol, led to a 1967 California law that made it illegal to carry a loaded firearm in public without a permit — a law signed by the Republican governor, Ronald Reagan.

Images of armed Black Panther Party members in leather jackets and berets outside the Capitol swept the nation and brought the group more fame, funding and notoriety.

Lee never formally joined the party but served as a community worker at a time when the group was pulling back from its more global revolutionary goals and focusing on volunteer work and building local political power in the East Bay Area.

Lee with her former boss, the late Rep. Ronald V. Dellums of Oakland, right, a progressive icon whom she would succeed in Congress, in an undated photo.

(Barbara Lee)

“It was mainly community service, and political awareness,” Lee said.

Previously, Lee had been an underclassman at Mills who brought her two sons to statistics class and led the Black Student Union. She had never registered with a political party, much less voted. Her focus — very much at the behest of her parents — was good grades and stability. She bought her first home near campus for about $19,000 through a federal program while she was still a student.

When she took a class that required students to volunteer on a 1972 presidential campaign, none of the candidates appealed to her.

“I said, ‘Flunk me, I’m not working in any of these guys’ campaigns,’” she recalled.

That winter, faced with the prospect of failing the class, she invited then-Rep. Shirley Chisholm, a New York Democrat, to speak on campus to the Black Student Union. Chisholm, described by the Oakland Tribune as “the dynamic little woman with the big voice,” spoke about the need for big countries to limit arms sales, stopping aid to countries that repress their citizens, and reducing discrimination in housing.

All of these subjects would become signature policy issues for Lee.

“America is at a crossroads today and it is going to take a combination of men, women, young people, Blacks, Chicanos and Indians — everything put together, not in a melting pot but in a salad bowl — to straighten it out,” Chisholm told the crowd.

After Chisholm announced her plans to run for president, Lee walked up to her and volunteered for her campaign. Eventually she rose to become the campaign’s organizing director in Northern California and one of the 28 delegates representing Chisholm at the 1972 Democratic National Convention in Miami Beach.

Lee on the campus of her alma mater, Northeastern University Oakland (formerly Mills College), last month.

(Loren Elliott / For The Times)

“Barbara had never even registered to vote before. But in the end they were to be responsible for a 9.6 percent vote for me in Alameda County,” Chisholm wrote in her memoir of Lee and another Mills College student, Sandra Gaines.

Lee and Gaines, Chisholm wrote, “could operate without having the aura of power and authority that an outside leader would have relied on.”

The 20-something Lee had begun to straddle the worlds of activism and more mainstream political work. The Chisholm campaign taught her how to organize and to be a sophisticated fundraiser — training that would stay with her. But the experience also alienated her from some of the Black Panthers activists she worked with, Lee recounted in her book.

“There were Black Panthers who accused me of being an FBI agent or simply part of ‘The System,’” she wrote.

She’d arrived in the Bay Area in the late 1960s as a single mom to two children and had survived a violent and abusive relationship. By the middle of the next decade, her activism and organizing work would help her overcome the pain she’d experienced and give her a sense of purpose from which to build.

Lee said the Panthers and her time at Mills College served as a bridge from a young adulthood marked by insecurity and grief, and molded the political worldview that would carry her into elected office.

“Being a part of the Black Panther movement toughened me up,” she wrote.

“It made me realize that racism, sexism, economic exploitation, poverty … are a by-product or result of a system of capitalism that relies on cheap labor and keeping people fighting each other rather than uniting and working together for the common good.”

Mourners gather for the funeral of Black Panther George Jackson at St. Augustine’s Episcopal Church in Oakland in 1971.

(Harold Adler / Underwood Archives / Getty Images)

This foray into politics launched a career in which she was able to maneuver inside the system as well. After Chisholm lost, Lee worked as fundraising coordinator for the 1973 Oakland mayoral campaign of Black Panther founder Bobby Seale, who took the Republican incumbent to a runoff but lost.

As Lee fell more fully into political work, she obtained a master’s degree in social work from UC Berkeley in 1975 and helped start Community Health Alliance for Neighborhood Growth and Education, or CHANGE Inc., a nonprofit that offered mental services to East Bay residents.

Elaine Brown, a former Black Panther Party chair, said Lee was driven to help people, whether inside the political system or outside it.

“You have a Joe Biden today, who would pretend that he is doing something, but he’s not. Barbara was true to her word,” Brown said. “She wanted to be elected so she could vote for things that would serve our interests. It wasn’t very complicated. It was very deep and very sincere.”

::

During a recent drive to St. Augustine’s Episcopal Church in west Oakland, Lee passed by large homeless encampments and boarded-up storefronts. The Black Panthers had served free breakfast for kids at the church — an experience that impressed upon her how government didn’t sufficiently care for the country’s neediest while focusing on military interventions abroad.

“It was always on my mind that what I saw then and now is because of systemic policies and institutional racism,” Lee said. “Back then I really felt I wasn’t just putting a Band-Aid on something.”

It was through political education classes, she said, that she’d come to understand “the circumstances that gave rise to this” system, but that “in the meantime, we had to help people survive.”

Lee poses outside St. Augustine’s Episcopal Church in Oakland, where she had participated in Black Panther Party events including serving free breakfast to kids.

(Loren Elliott / For The Times)

Lee eventually became chief of staff for Rep. Ronald V. Dellums (D-Oakland), a progressive icon whom she would succeed in Congress. In the mid-1990s, after she had returned to Oakland to run a facilities management company, it was Dellums’ political network that lured her back to politics, urging — really cajoling — her to run for an open state Assembly seat.

“She pays attention to what people’s needs are and hears them. She’s intellectually brilliant at composing solutions for problems both at an individual and social scale,” said Lee Halterman, who spent 27 years working for Dellums and advised some of Lee’s early campaigns.

“We wanted to continue the coalition idea,” Halterman said, “that in districts that can send people of color to Congress, that should be a priority.”

In 1998, after Dellums resigned midway through his term, Lee won a special election for his House seat.

Sitting in a coffee shop around the corner from St. Augustine’s Church, Lee doused a slice of avocado toast in hot sauce and sipped a honey oat lavender latte. Three constituents of Ethiopian descent came up to thank her for her office’s help dealing with some paperwork problems on a citizenship application.

Lee in front of her former home in Oakland last month.

(Loren Elliott / For The Times)

There’s been less time in recent years for Lee to visit these moments from her past and connect with this history. The COVID-19 pandemic meant that she spent less time at in-person events. The Senate campaign has meant she’s traversing the state more when she’s not in Washington for votes.

She recalled a piece of advice from Dellums: “He would always say this to me: ‘Stand on the corner — by yourself. Just stand there. Sooner or later, everybody is going to walk to you if you’re on the right side of the issue.’”

Politics

Iran fires missiles at US bases across Middle East after American strikes on nuclear, IRGC sites

NEWYou can now listen to Fox News articles!

Iran launched missile and drone strikes targeting U.S. military facilities in multiple Middle Eastern countries Friday, retaliating after coordinated U.S.–Israeli strikes on Iranian military and nuclear-linked sites.

Explosions were reported in or near areas hosting American forces in Bahrain, Qatar, the United Arab Emirates, Kuwait and Jordan, according to regional officials and state media accounts. Several of those governments said their air defense systems intercepted incoming projectiles.

It remains unclear whether any U.S. service members were killed or injured, and the extent of potential damage to American facilities has not yet been confirmed. U.S. officials have not publicly released casualty figures or formal damage assessments.

Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) described the operation as a direct response to what Tehran called “aggression” against Iranian territory earlier in the day. Iranian officials claimed they targeted U.S. military infrastructure and command facilities.

Explosions were reported in or near areas hosting American forces in Bahrain, pictured above. (Photo by Petty Officer 2nd Class Adelola Tinubu/U.S. Naval Forces Central Command/U.S. 5th Fleet )

The United States military earlier carried out strikes against what officials described as high-value Iranian targets, including IRGC facilities, naval assets and underground sites believed to be associated with Iran’s nuclear program. One U.S. official told Fox News that American forces had “suppressed” Iranian air defenses in the initial wave of strikes.

Tomahawk cruise missiles were used in the opening phase of the U.S. operation, according to a U.S. official. The campaign was described as a multi-geographic operation designed to overwhelm Iran’s defensive capabilities and could continue for multiple days. Officials also indicated the U.S. employed one-way attack drones in combat for the first time.

IF KHAMENEI FALLS, WHO TAKES IRAN? STRIKES WILL EXPOSE POWER VACUUM — AND THE IRGC’S GRIP

Smoke rises after reported Iranian missile attacks, following strikes by the United States and Israel against Iran, in Manama, Bahrain, Feb. 28, 2026. (Reuters)

Iran’s retaliatory barrage targeted countries that host American forces, including Bahrain — home to the U.S. Navy’s Fifth Fleet — as well as Qatar’s Al Udeid Air Base and the UAE’s Al Dhafra Air Base. Authorities in those nations reported intercepting many of the incoming missiles. At least one civilian was killed in the UAE by falling debris, according to local authorities.

Iranian officials characterized their response as proportionate and warned of additional action if strikes continue. A senior U.S. official described the Iranian retaliation as “ineffective,” though independent assessments of the overall impact are still developing.

Smoke rises over the city after the Israeli army launched a second wave of airstrikes on Iran in Tehran on Feb. 28, 2026. (Fatemeh Bahrami/Anadolu via Getty Images)

CLICK HERE TO DOWNLOAD THE FOX NEWS APP

Regional governments condemned the strikes on their territory as violations of sovereignty, raising the risk that additional countries could become directly involved if escalation continues.

The situation remains fluid, with military and diplomatic channels active across the region. Pentagon officials are expected to provide further updates as damage assessments and casualty reviews are completed.

Fox News’ Jennifer Griffin contributed to this report.

Politics

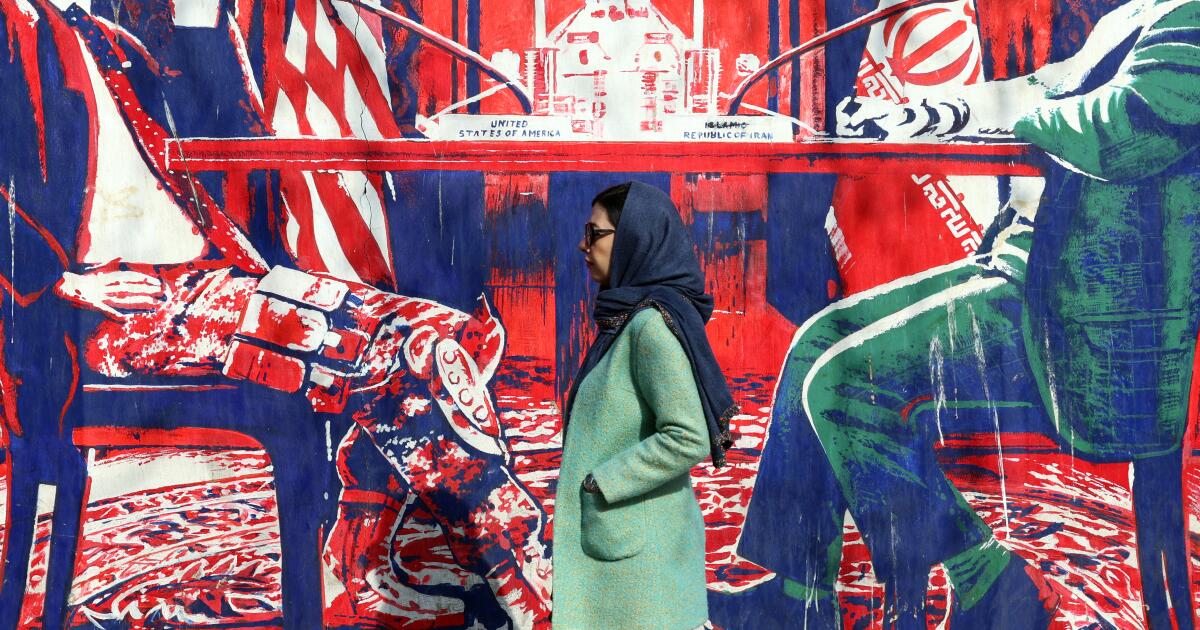

Why Iran resists giving up its nuclear program, even as Trump threatens strikes

Embassy staffers and dependents evacuating, airlines suspending service, eyes in Iran warily turning skyward for signs of an attack.

The prospects of a showdown between the U.S. and Iran loom ever higher, as massive American naval and air power lies in wait off Iran’s shores and land borders.

Yet little of that urgency is felt in Iran’s government. Rather than quickly acquiescing to President Trump’s demands, Iranian diplomats persist in the kind of torturously slow diplomatic dance that marked previous discussions with the U.S., a pace that prompted Trump to declare on Friday that the Iranians were not negotiating in “good faith.”

But For Iran’s leadership, Iranian experts say, concessions of the sort Trump are asking for about nuclear power and the country’s role in the Middle East undermine the very ethos of the Islamic Republic and the decades-old project it has created.

“As an Islamic theocracy, Iran serves as a role model for the Islamic world. And as a role model, we cannot capitulate,” said Hamid Reza Taraghi, who heads international affairs for Iran’s Islamic Coalition Party, or Hezb-e Motalefeh Eslami.

Besides, he added, “militarily we are strong enough to fight back and make any enemy regret attacking us.”

Even as another round of negotiations ended with no resolution this week, the U.S. has completed a buildup involving more than 150 aircraft into the region, along with roughly a third of all active U.S. ships.

Observers say those forces remain insufficient for anything beyond a short campaign of a few weeks or a high-intensity kinetic strike.

Iran would be sure to retaliate, perhaps against an aircraft carrier or the many U.S. military bases arrayed in the region. Though such an attack is unlikely to destroy its target, it could damage or at least disrupt operations, demonstrating that “American power is not untouchable,” said Hooshang Talé, a former Iranian parliamentarian.

Tehran could also mobilize paramilitary groups it cultivated in the region, including Iraqi militias and Yemen’s Houthis, Talé added. Other U.S. rivals, such as Russia and China, may seize the opportunity to launch their own campaigns elsewhere in the world while the U.S. remains preoccupied in the Middle East, he said.

“From this perspective, Iran would not be acting entirely alone,” Tale said. “Indirect alignment among U.S. adversaries — even without a formal alliance — would create a cascading effect.”

We’re not exactly happy with the way they’re negotiating and, again, they cannot have nuclear weapons

— President Trump

The U.S. demands Iran give up all nuclear enrichment and relinquish existing stockpiles of enriched uranium so as to stop any path to developing a bomb. Iran has repeatedly stated it does not want to build a nuclear weapon and that nuclear enrichment would be for exclusively peaceful purposes.

The Trump administration has also talked about curtailing Iran’s ballistic missile program and its support to proxy groups, such as Hezbollah, in the region, though those have not been consistent demands. Tehran insists the talks should be limited to the nuclear issue.

After indirect negotiations on Thursday, Oman’s Foreign Minister Badr al-Busaidi — the mediator for the talks in Geneva — lauded what he said was “significant progress.” Iranian Foreign Ministry spokesman Esmail Baghaei said there had been “constructive proposals.”

Trump, however, struck a frustrated tone when speaking to reporters on Friday.

“We’re not exactly happy with the way they’re negotiating and, again, they cannot have nuclear weapons,” he said.

Trump also downplayed concerns that an attack could escalate into a longer conflict.

This frame grab from footage circulating on social media shows protesters dancing and cheering around a bonfire during an anti-government protest in Tehran, Iran, on Jan. 9.

(Uncredited / Associated Press)

“I guess you could say there’s always a risk. You know, when there’s war, there’s a risk in anything, both good and bad,” Trump said.

Three days earlier, in his State of the Union address Tuesday, said, “My preference is to solve this problem through diplomacy. But one thing is certain, I will never allow the world’s number one sponsor of terror, which they are by far, to have a nuclear weapon — can’t let that happen.”

There are other signs an attack could be imminent.

On Friday, the U.S. Embassy in Israel allowed staff to leave the country if they wished. That followed an earlier move this week to evacuate dependents in the embassy in Lebanon. Other countries have followed suit, including the U.K, which pulled its embassy staff in Tehran. Meanwhile, several airlines have suspended service to Israel and Iran.

A U.S. military campaign would come at a sensitive time for Iran’s leadership.

The country’s armed forces are still recovering from the June war with Israel and the U.S, which left more than 1,200 people dead and more than 6,000 injured in Iran. In Israel, 28 people were killed and dozens injured.

Unrest in January — when security forces killed anywhere from 3,000 to 30,000 protesters (estimates range wildly) — means the government has no shortage of domestic enemies. Meanwhile, long-term sanctions have hobbled Iran’s economy and left most Iranians desperately poor.

Despite those vulnerabilities, observers say the U.S. buildup is likely to make Iran dig in its heels, especially because it would not want to set the precedent of giving up positions at the barrel of a U.S. gun.

Other U.S. demands would constitute red lines. Its missile arsenal, for example, counts as its main counter to the U.S. and Israel, said Rose Kelanic, Director of the Middle East Program at the Defense Priorities think tank.

“Iran’s deterrence policy is defense by attrition. They act like a porcupine so the bear will drop them… The missiles are the quills,” she said, adding that the strategy means Iran cannot fully defend against the U.S., but could inflict pain.

At the same time, although mechanisms to monitor nuclear enrichment exist, reining in Tehran’s support for proxy groups would be a much harder matter to verify.

But the larger issue is that Iran doesn’t trust Trump to follow through on whatever the negotiations reach.

After all, it was Trump who withdrew from an Obama-era deal designed to curb Iran’s nuclear ambitions, despite widespread consensus Iran was in compliance.

Trump and numerous other critics complained Iran was not constrained in its other “malign activities,” such as support for militant groups in the Middle East and development of ballistic missiles. The Trump administration embarked on a policy of “maximum pressure” hoping to bring Iran to its knees, but it was met with what Iran watchers called maximum resistance.

In June, he joined Israel in attacking Iran’s nuclear facilities, a move that didn’t result in the Islamic Republic returning to negotiations and accepting Trump’s terms. And he has waxed wistfully about regime change.

“Trump has worked very hard to make U.S. threats credible by amassing this huge military force offshore, and they’re extremely credible at this point,” Kelanic said.

“But he also has to make his assurances credible that if Iran agrees to U.S. demands, that the U.S. won’t attack Iran anyway.”

Talé, the former parliamentarian, put it differently.

“If Iranian diplomats demonstrate flexibility, Trump will be more emboldened,” he said. “That’s why Iran, as a sovereign nation, must not capitulate to any foreign power, including America.”

Politics

Video: Bill Clinton Says He ‘Did Nothing Wrong’ in House Epstein Inquiry

new video loaded: Bill Clinton Says He ‘Did Nothing Wrong’ in House Epstein Inquiry

transcript

transcript

Bill Clinton Says He ‘Did Nothing Wrong’ in House Epstein Inquiry

Former President Bill Clinton told members of the House Oversight Committee in a closed-door deposition that he “saw nothing” and had done nothing wrong when he associated with Jeffrey Epstein decades ago.

-

“Cause we don’t know when the video will be out. I don’t know when the transcript will be out. We’ve asked that they be out as quickly as possible.” “I don’t like seeing him deposed, but they certainly went after me a lot more than that.” “Republicans have now set a new precedent, which is to bring in presidents and former presidents to testify. So we’re once again going to make that call that we did yesterday. We are now asking and demanding that President Trump officially come in and testify in front of the Oversight Committee.” “Ranking Member Garcia asked President Clinton, quote, ‘Should President Trump be called to answer questions from this committee?’ And President Clinton said, that’s for you to decide. And the president went on to say that the President Trump has never said anything to me to make me think he was involved. “The way Chairman Comer described it, I don’t think is a complete, accurate description of what actually was said. So let’s release the full transcript.”

By Jackeline Luna

February 27, 2026

-

World3 days ago

World3 days agoExclusive: DeepSeek withholds latest AI model from US chipmakers including Nvidia, sources say

-

Massachusetts3 days ago

Massachusetts3 days agoMother and daughter injured in Taunton house explosion

-

Montana1 week ago

Montana1 week ago2026 MHSA Montana Wrestling State Championship Brackets And Results – FloWrestling

-

Louisiana5 days ago

Louisiana5 days agoWildfire near Gum Swamp Road in Livingston Parish now under control; more than 200 acres burned

-

Denver, CO3 days ago

Denver, CO3 days ago10 acres charred, 5 injured in Thornton grass fire, evacuation orders lifted

-

Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoYouTube TV billing scam emails are hitting inboxes

-

Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoStellantis is in a crisis of its own making

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoOpenAI didn’t contact police despite employees flagging mass shooter’s concerning chatbot interactions: REPORT