Entertainment

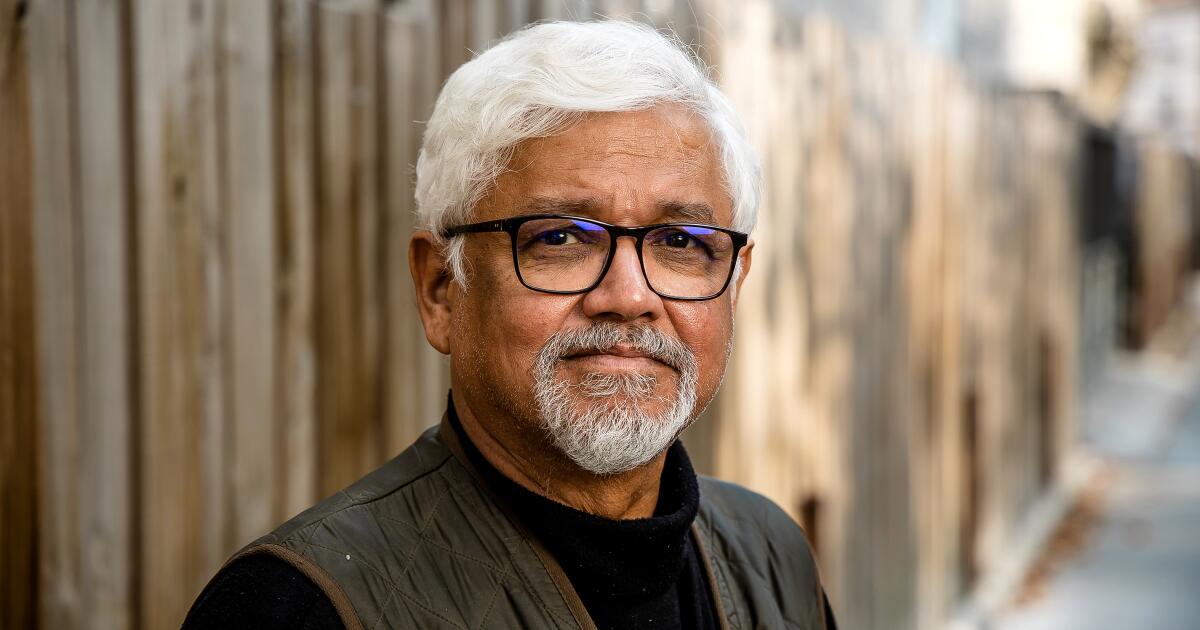

China, opium and racial capitalism: Amitav Ghosh on the roots of a deadly business

On the Shelf

‘Smoke and Ashes: Opium’s Hidden Histories’

By Amitav Ghosh

Farrar, Straus and Giroux: 416 pages, $32

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

After the mid-18th century, when the British East India Co. was importing tea from China, few could have guessed that the industry would be revolutionized by a different plant: the opium poppy. Over the next century and beyond, Britain and other colonial powers, joined by American and Indian merchants, amassed unimaginable wealth by getting the Chinese addicted to opium. It was opium money from trade with China that primarily funded the expansion of so many Western corporations and institutions.

In his latest book, “Smoke and Ashes: Opium’s Hidden Histories,” Amitav Ghosh subverts Eurocentric history and digs open the recesses of racial capitalism, specifically Indian farmers coerced into growing poppy and the consequent pumping of opium into China. Ghosh exposes the hypocrisy of the Western world in perpetrating structural violence against Asians under the garb of free trade and progress and the uncanny similarities between the Machiavellian tactics of the opium business in China and of those who triggered the modern-day American opioid crisis. This conversation has been edited lightly.

China has long been perceived as an alien culture by the West. It has been demonized time and again, and after the COVID-19 outbreak, the animosity toward China has only worsened. But most Americans aren’t aware of the legacy in America of merchants who made their fortune in Guangzhou (Canton). Could you throw more light on that?

It might come as a shock to most readers that the U.S. has been dependent on China right from the very start. In 1783, when America was born, it was unable to trade with any of its neighbors that were still part of the British Empire. So, the Americans realized that it was essential for them to trade with China. In fact, one of the grievances that led to the birth of the U.S. was that the Americans were initially prohibited from trading with China because the trade was in the hands of the British East India Co. There was a lot of resentment against the East India Co.’s monopoly over tea. So almost immediately after the birth of the republic, China became the primary trading partner for the U.S. But the problem that the U.S. had in relation to China was the same that the British had — that the world again has today in relation to China — that the whole world buys Chinese goods, but the world doesn’t have any goods or enough goods to sell to China apart from resources because the Chinese make everything themselves. China was then, as it is now, the world’s great manufacturing hub.

(Farrar, Straus and Giroux)

So many of the technologies that we know today were stolen from China by the West, such as porcelain, gunpowder, compasses and bank deposit insurance. When the Americans started trading with China in the late 18th century, they started with furs and later sandalwood, but soon they just couldn’t find enough stuff to sell to China. So eventually they started doing what the British did: They started selling opium to China, sourced initially from Turkey and then later from India. For many generations, young Americans, especially very privileged white men predominantly from Massachusetts and other parts of New England and New York, would travel to China, and they would come back within four or five years with these immense fortunes. China gave them the experience of doing global trade, understanding currencies and foreign exchange, etc. They also became aware of the new industries that were then arising in Europe because of the Industrial Revolution. So, they came back to the U.S. and became the founders of all these modern industries, most importantly, perhaps the railroads.

You’ve drawn parallels between the Chinese opium crisis and the American opioid crisis. The British blamed the Chinese for being corrupt and mentally feeble. According to the British, they were simply meeting the Chinese demand for opium. Whereas we’ve seen in the American opioid crisis that it’s not demand but supply that dictates the flow of opium, as is evident in the case of the five states that had additional regulations to curb the prescription of opioids. These states (California, Idaho, New York, Texas and Illinois) experienced low growth in overdose deaths. So, it’s clear that it is supply and not demand that controls opium.

Initially, the British had trouble selling even 500 crates of opium to China, but once it got on, it was like a forest fire, and by the end of the 19th century, the Chinese were consuming hundreds of thousands of crates of Indian opium. So, when the anti-opium movement tried to constrain the British Empire from selling opium, the British deflected the blame onto the Chinese demand for it. This is essentially what the Sackler family also said in America when they introduced OxyContin; addicts were blamed. The British “logic”: There’s a demand for it, and if we don’t meet it, then someone else will.

The Sacklers were aided by a lot of historians and academicians who put forth revisionist arguments in favor of rehabilitating opioids. They even took the FDA into confidence, right?

That’s right. It wasn’t until the victims’ families began to protest in a very big way that the narrative changed. Until then, the people who were defending opiates had control of the narrative for the longest time. I think it’s also important to note that this kind of opioid crisis seems to go hand-in-hand with a certain kind of civilizational crisis. That was certainly the case with China when it started getting engulfed in the web of opium in the late 18th century. Suddenly, it found itself having to question its ideas of centrality in the world. It was facing, literally, an existential threat.

I think something very similar is happening in America today. There’s really a profound sense of civilizational crisis. And for ordinary Americans, they are facing life conditions that are unimaginably difficult. In a way, the opioid crisis took off because of all these other factors within society. Deindustrialization was happening, and old mining communities were disintegrating. Opium was sold to extremely vulnerable communities where there was a lot of pain and social difficulties. So, we really see a kind of playing out of what happened in China in the 19th century.

The anti-opium movement in the early 20th century rattled the British Empire, and eventually China succeeded in getting most of its population off opium. You’ve pointed out in your book that one of the problems with the American war on drugs was that it pinned the blame not only on the producers but also on the consumers, whereas the anti-opium drive only targeted the producers. The Chinese establishment ensured that they treated the addicts with sympathy.

This is the problem, really. The war on drugs was a state-led movement initiated by the U.S. armed forces and its security establishment. And there was a kind of double dealing involved because the Americans were using heroin, etc. in their conflicts in Southeast Asia, Latin America and so on. At the same time, they were also trying to suppress cocaine and other drugs, and they created an incredible mess. The first problem with the war on drugs is the idea of what exactly constitutes a drug. Many of the substances that they banned and considered drugs were, as we now know, in many ways beneficial to humanity.

Now they’ve changed strategies. More and more states are recognizing that many substances they call drugs are actually very beneficial, like psilocybin mushrooms, which can be used to treat depression. America now finds itself trying to control the circulation of heroin, fentanyl, etc. The problem is that again, it’s a state-led initiative, and it’s failing. Opioid-related deaths peaked during COVID-19, and it was thought that after the epidemic they would tail off. But no, it’s only continued to grow. Especially because fentanyl is so cheap and easily available, more and more people are dying of substance abuse.

What happened in Asia in the late 19th century and early 20th century was a very remarkable thing. You saw the emergence of a popular grassroots movement that was opposed to the free circulation of opioids, and that was effective. Even though, in China, the addiction problem continued until the 1950s, when, finally, the Communist Party did crack down on it. I don’t think any country will be able to reproduce that today.

One of the problems with addiction is that it happens indoors; the victims are out of sight. If you just look around America today, you wouldn’t think there was a problem. Many people who traveled to China in the 19th century thought everything was fine, but it wasn’t. In recent years, the U.S. Army has not been able to meet its recruitment goals. A recent survey found that not even 25% of young Americans are eligible to serve in the Army, partly because of obesity, mental health problems or drug use. Now that is a crisis.

Movie Reviews

Peaky Blinders: The Immortal Man review – Tommy Shelby returns for muddy, bloody big-screen showdown

After six TV series from 2013 to 2022, which caused a worrying surge in flat cap-wearing among well-to-do men in country pubs, Peaky Blinders is now getting a hefty standalone feature film, a muscular picture swamped in mud and blood. This is the movie version of Steven Knight’s global small-screen hit, based on the real-life gangs that swaggered through Birmingham from Victorian times until well into the 20th century. Cillian Murphy returns with his uniquely unsettling, almost sightless stare as Tommy Shelby, family chieftain of a Romani-traveller gang, a man who has converted his trauma in the trenches of the first world war into a ruthless determination to survive and rule.

As we join the story some years after the curtain last came down, it is 1940, Britain’s darkest hour and Tommy is the crime-lion in winter. He now lives in a huge, remote mansion, far from the Birmingham crime scene he did so much to create, alone except for his henchman Johnny Dogs, played by Packy Lee. Evidently wearied and sickened by it all, Tommy is haunted by his ghosts and demons: memories of his late brother, Arthur, and dead daughter, Ruby, and working on what will be his definitive autobiography. (Sadly, we don’t get any scenes of Tommy having lunch with a drawling London publisher or agent.)

But a charismatic and beautiful woman, played by Rebecca Ferguson, brings Tommy news of what we already know: his malign idiot son Erasmus Shelby, played by Barry Keoghan, is now running the Peaky Blinders, a new gen-Z-style group of flatcappers raiding government armouries for guns that should really belong to the military. And if that wasn’t disloyal and unpatriotic enough, Erasmus has accepted a secret offer from a sinister Nazi fifth-columnist called Beckett, played by Tim Roth, to help distribute counterfeit currency which will destroy the economy and make Blighty easier to invade. Doesn’t Erasmus know what Adolf Hitler is going to do to his own Romani people? (To be fair to Erasmus, a lot of the poshest and most well-connected people in the land didn’t either.)

Clearly, Tommy is going to have to come down there and sort this mess out. And we get a very ripe scene in which soft-spoken Tommy turns up in the pub full of raucous idiots who cheek him. “Who the faaaaaack is ‘Tommy Shelby’?” sneers one lairy squaddie, who gets horribly schooled on that very subject.

In this movie, Tommy Shelby is against the Nazis, and he can’t get to be more of a good guy than that. (Tommy has evidently put behind him memories of Winston Churchill from the first two series, when Churchill was dead set on clamping down on the Peaky Blinders.) The war and the Nazis are a big theme for a big-screen treatment and screenwriter Knight and director Tom Harper put it across with some gusto as a kind of homefront war film, helped by their effortlessly watchable lead. Maybe you have to be fully invested in the TV show to really like it, although this canonisation of Tommy is a sentimental treatment of what we actually know of crime gangs in the second world war. Nevertheless, it is a resoundingly confident drama.

Entertainment

Jo Koy and Fluffy’s sold-out SoFi show marks a turning point for stand-up comedy

Running free during a game of catch on the empty field at SoFi Stadium is a fantasy most Angelenos will never experience. For comedians Jo Koy and Gabriel Iglesias, it’s just a warm-up to a dream that’s been a lifetime in the making.

Gripping the football with fingers covered in Filipino tribal tattoos extending in a sleeve up his arm, Koy looks across the expanse of emerald green turf at his son jogging toward the south end zone of the Inglewood stadium on a recent afternoon. “To be able to throw at SoFi is crazy,” Koy said with a sparkling grin of bright white veneers.

The 54-year-old comedian with a beard full of gray stubble drops back to pass, launching a tight spiral underneath SoFi’s massive technicolor halo scoreboard hovering above a sea of empty stands. Joseph Jr. — a wiry 22-year-old with a head full of curly dark brown hair — runs briskly toward the goal line with a black cast on his left arm. He raises his right arm just in time to scoop it into his chest for a touchdown. The imaginary crowd goes wild.

“Yes!!!” Koy shouts, his excitement echoing in the stadium. He jogs over to Joseph in his navy blue coverall jumpsuit and L.A. Dodgers cap to deliver a satisfying father-son chest bump.

A few yards away, Iglesias is watching Roka, his tiny black chihuahua, dart around the field like four pounds of rambunctious entitlement. The plus-sized comedian — better known as “Fluffy” — is sporting his typical loose-fitting vintage Hawaiian shirt, denim shorts and black flat cap. Whenever they stand together, the duo’s dynamic is like a modern-day Laurel and Hardy.

Nearly 70% of tickets for Koy and Iglesias’ SoFi show sold within days, making this the largest stadium stand-up performance to date.

(Christina House/Los Angeles Times)

“The fact that we’ve known each other as long as we have is wild … we’ve known each other since we both had hair,” Iglesias, 49, says as they both lift up their caps in unison, laughing and exposing their shiny bald heads.

On March 21, this stadium will be filled with more than 70,000 guests as the pair takes center stage at the Super Bowl of comedy — the largest stadium stand-up show to date. Koy and Iglesias are now part of a small fraternity of comics, including Kevin Hart, Dane Cook, Bill Burr and Larry the Cable Guy, who’ve sold out stadiums across the country.

The one-night-only show, which won’t be televised or recorded as a special, is meant to be one giant party for comedy fans who’ve supported Koy and Iglesias since their early days. The comics will be passing the mic back and forth throughout the night, which will feature special guests, surprise moments and plenty of other unplanned interruptions that will make for a roughly four-hour show. Though the L.A. comedy scene tends to exist in the shadow of Hollywood, this feat managed by two of its biggest names puts a historic spotlight on stand-up.

“It’s more sweet because it’s taken so long,” Iglesias said. “This wasn’t an overnight thing. Nowadays, everybody wants everything so fast. Between the two of us, we’ve got about 60 years of comedy experience.”

“It’s insane. I can’t explain it,” Koy adds, staring up at the stadium’s glass roof, preparing to crack it with decibels of laughter. “Every time we come in here and look up, I’m like, ‘There’s going to be a stage here the size of the end zone.’ We took the stage from the arenas that we normally play and injected steroids into it.”

For comedians who’ve witnessed their ascent, which now literally includes hands and feet cemented in front of TCL Chinese Theatre and a star for Fluffy on the Hollywood Walk of Fame, the journey has been incredible to watch.

“It’s huge for stand-up, it used to be just in dingy clubs and bars and always something small and intimate and kinda like an afterthought,” said fellow comedy star Tiffany Haddish, a longtime friend to both Koy and Iglesias. “To be honest I never thought comedy would be this big.”

Jay Leno, a confidant to Iglesias and the man who inspired him to start his own insane car collection and offered Koy his first late-night appearance on “The Tonight Show,” agrees that a show like this is a huge step for comedy.

“My attitude when I came to this town was if you can’t get in through the front door, go in the back door,” Leno said. “And they didn’t do it the traditional way, they got to where they are as comedians, one audience member at a time.”

For the two L.A. comedians, the historic milestone represents decades of work and signals comedy’s arrival in mainstream entertainment venues.

(Christina House/Los Angeles Times)

When the pair of arena-selling comics announced last year they’d be joining forces to perform at SoFi, the task of filling the massive concert venue and football stadium seemed laughable. But within a week, it clearly wasn’t a joke. Nearly 70% of the tickets were sold just days after going on sale. Now, weeks before the gig, the show is completely sold out with more seats being added. If there’s one person who is not necessarily surprised, it’s Iglesias. By his calculations — including his ability to sell out Dodger Stadium twice for the filming of his 2022 Netflix special, “Stadium Fluffy,” and Koy’s ability to sell out the Forum a record-setting six consecutive times (more than any other comedian) — the math checked out.

“At a certain point it’s like we’ve been doing [huge stand-up shows] for so many years, it becomes normal,” Iglesias said. “What do you do to change things? What do you do to grow? The worst thing that happens is it fails. But at least we know we tried it. Then we know what our ceiling is. But as of now, this isn’t the ceiling.”

Despite the logic, looking at the stadium’s massive seating chart during an initial meeting with the venue made the task feel akin to climbing Mt. Everest.

“SoFi is the size of like five Forums. That seating chart on a wall was the most discouraging thing I could possibly look at,” Koy said. “And then looking at the amount of money it was gonna cost us even before we sell one ticket. Me and Gabe should’ve been looking at that and been like, ‘What … are we thinking? Hell nah we ain’t doing this … !’”

It took more than a little convincing from Iglesias to get Koy on board. “[Jo] does not like change. I had to break down the math for him and I pushed it a lot,” Iglesias said. “And I’m glad we did because now that it’s sold out, the hard part is over. We just have to show up and deliver a kick-ass show. And then we can both celebrate after, crack a couple bottles and I know I’m taking a week off after that.”

Unlike a typical arena show, which takes several months to coordinate, their big night at SoFi required a full year of planning. The production and stage will be three times the size of the comedians’ normal stages and will be managed by the same team that produces stadium shows for acts like Los Bukis and Bad Bunny.

“It’s more sweet because it’s taken so long,” Iglesias said. “This wasn’t an overnight thing. Nowadays, everybody wants everything so fast. Between the two of us, we’ve got about 60 years of comedy experience.”

(Christina House/Los Angeles Times)

“It’s almost like a chessboard,” Iglesias said. “You got to do a bunch of moves in order to pull something like this off, it’s not just we’re gonna do it. This took a lot of planning, a lot of coordinating.”

When asked how the tickets could’ve possibly moved so fast, outside of typical avenues of good marketing and promotion, Koy says it was really comedy fans making a statement of support for them and for stand-up.

“There’s no such thing as marketing on this one, to me it’s a phenom,” he said, noting the pride both he and Iglesias have to see the excitement and support from local fans, especially Filipino and Latin communities across L.A. that have been a major part of their respective fanbases. “That type of reaction and that response to us saying we’re gonna be at SoFi is almost like a bragging right and it’s ‘our night, we’re gonna be there, I don’t care where we’re sitting.’”

The SoFi gig was conceived in February of 2024 during Koy’s sixth sold-out show at Kia Forum. In the hoopla of Koy breaking his own audience record at the venue, Iglesias crashed the show, presented his friend with a plaque and laid down the gauntlet in front of 17,500 fans. When Iglesias asked Koy if they should contemplate performing “across the street” together, the crowd erupted with excitement.

“Our agents and managers were like, ‘Are you sure you wanna do that?’’’ Iglesias said. “I think they missed a couple bonuses. But at the end of the day, it’s part of history.”

“That’s what’s beautiful about Gabe, he’s not scared to take on those big risks,” Koy said. “But the whole thing was a risk. We gotta alter our tour dates and sacrifice other opportunities to make this happen.”

“Every time we come in here and look up, I’m like, ‘There’s going to be a stage here the size of the end zone,‘” Koy said about the upcoming SoFi show on Mar. 21. “We took the stage from the arenas that we normally play and injected steroids into it.”

(Christina House/Los Angeles Times)

For Koy, a life of comedy was a risk inspired by his heroes while growing up in Tacoma, Wash. He traces it back to being 15 and seeing Eddie Murphy perform at Climate Pledge Arena during his “Raw” tour in Seattle. He remembers taking a panoramic look at the sold-out crowd roaring in the darkness before the leather-suited legend even took the stage. “I’m like, ‘Wait a minute, this guy got this many people in here?’ I just thought that was the most impossible thing,” Koy remembers. “And now I get to share this moment with my son and let him walk with me and let him see that this is possible.”

When Koy was moving up the comedy ranks under his real name Joseph Glenn Herbert, the thought of calling himself a comedian felt like a pipe dream. Koy, the son of a white father and Filipina mother, saw comedy as a way to channel an overactive personality and need to make people laugh into a career. Going from coffee shop open mics in Tacoma to clubs and casinos in Las Vegas in 1989, Koy scratched out a living doing random jobs to move to L.A. in 2001 with hopes of making it big.

Working at a bank or Nordstrom Rack offered some stability as he drove up and down Sunset Boulevard in his battered Honda Prelude with one broken headlight, looking for a way forward to pursue his passion. Haddish, his longtime friend, spent years working with Koy, who served as her mentor at the Laugh Factory. Between sets on stage, the two would often take breaks to fantasize about fame.

“Jo and I would sit outside of the Laugh Factory and have these conversations and we’d be eating hot dogs wrapped in bacon and we’d be dreaming about being in a big movie, playing big theaters and helping people heal through laughter,” Haddish said. “Now here we are.”

“At the end of the day, this is a big stamp. And I think it also lets other comics know, ‘Hey, man, step up your game. Let’s grow this,’” Iglesias said.

(Christina House/Los Angeles Times)

Pulling off a show of this magnitude is jaw-dropping to think about, Iglesias said, even after having achieved a similar feat just a few years ago at Dodgers Stadium where he filmed his special over the course of two shows. He also set a record for fines incurred by a performer for going over his allotted time slot (a hefty $250,000 for not leaving the venue until 4 a.m.). The SoFi gig leaves him only one shot to get it right. This time around, Iglesias feels infinitely less pressure despite the bigger venue.

“[Dodger Stadium] for me was grueling,” Iglesias said. “I didn’t know what to expect, I didn’t know how it was gonna go. Every day we were pulling our hair out trying to figure it out. Fortunately we were still able to pull it off and we learned a lot from it. This time around, believe me when I tell you the stress of this show is not even there.”

Iglesias, a native of Long Beach, has spent over 30 years rising up the comedy ranks. Among his accomplishments are seven major comedy specials, a TV show (“Mr. Iglesias”) and becoming the first Mexican American comic with a top-grossing worldwide tour. Like Koy, who also has seven major specials, Iglesias went through a lot of metamorphosis on stage prior to finding his calling as a gregarious, fun-loving comedian with a penchant for doing cartoon-ish voices.

Leno says one of the key factors in Fluffy’s mass appeal is his likability.

“The great thing about Gabriel is that the kindness comes across, there’s not a mean spirit in his body,” he said. “There’s a lot of comics who are really funny but people don’t like them because they think they’re mean-spirited. … When you watch Gabe even when he does something that’s not fall-down hysterical, you smile because you like him. … I find him a joy to watch.”

Much of what Iglesias learned about marketing himself was inspired by the WWE. The costumes, witty banter and theatrics of the wrestling ring influenced his consistent look and even allowed the name “Fluffy” to become his calling card.

Comedians Gabriel Iglesias, aka, “Fluffy,” in front, and Jo Koy are photographed at SoFi Stadium in Inglewood on February 10, 2026, ahead of their March 21st show.

(Christina House/Los Angeles Times)

“There is a certain level of pandemonium, as they say in wrestling, that’s needed to get people excited,” Iglesias said. “Then there’s the marketing and the way that you do it — so I did study wrestling a lot.”

Handing the kingdom of SoFi over to the court jesters for a night is a feat worthy of celebration.

“At the end of the day, this is a big stamp. And I think it also lets other comics know, ‘Hey, man, step up your game. Let’s grow this,’” Iglesias said. “And it’s not, ‘Step up your game,’ like we’re competing with each other. It’s more so like, ‘Let’s elevate the game of comedy.’”

Right now Koy feels plenty elevated, as though he’s floating every time he enters the stadium and looks up at the stands — like the night he saw Eddie Murphy all those years ago.

“You should’ve heard the whispers me and Gabe had to ourselves walking out of the stadium tunnel, like, ‘Yo, is this really happening?!’” Koy said with a megawatt smile. “Coming from an open mic night at a coffee house, never in my wildest dreams did I say, ‘Someday, a football stadium’ … we’re literally living our dreams right now.”

Movie Reviews

Movie Review: Here comes “THE BRIDE!”, audacious and wild – Rue Morgue

That’s both a promise and a challenge she delivers, since what follows may rub some viewers the wrong way. Yet Gyllenhaal’s full-throttle commitment to her vision is compelling in and of itself, and she has marshalled an absolutely smashing-looking and -sounding production. The story proper begins in 1936 Chicago, which, like everything and everyplace else in the movie, has been luminously shot by cinematographer Lawrence Sher and sumptuously conjured by production designer Karen Murphy. Her involvement is appropriate given that her previous credits include Bradley Cooper’s A STAR IS BORN and Baz Luhrmann’s ELVIS, since among other things, THE BRIDE! is a nostalgic musical. Its Frankenstein (Christian Bale), who has taken the name of his maker, is obsessed with big-screen tuners, and imagines himself in elaborate song-and-dance numbers. (Considering the reception to JOKER: FOLIE À DEUX, one must applaud the daring of Warner Bros. for greenlighting another expensive film in which a tormented protagonist has that kind of fantasy life.)

THE BRIDE! may be revisionist on many levels, but its characterization of its “monster” holds true to past screen incarnations from Karloff’s to Elordi’s: His scarred appearance masks a lonely soul who desires companionship. Frankenstein has arrived in Chicago to seek out Dr. Cornelia Euphronious (Annette Bening), correctly believing she has the scientific know-how to create an appropriate mate for him. Rather than piece one together, Dr. Euphronious resurrects the corpse of Ida (Jessie Buckley), whose consorting with underworld types led to her brutal death. Previously chafing against the man’s world she inhabited in life, she becomes even more defiant and unruly as a revenant, apparently possessed by the spirit of Shelley herself, declaiming in free-associative sentences and quoting rebellious literature.

Buckley, currently an Oscar favorite for her very different literary-inspired role in HAMNET, tears into the role of the Bride (who now goes by the name Penny) with invigorating abandon that bursts off the screen. Unsure of her identity yet overflowing with self-confident bravado, she’s the opposite of the sensitive “Frank,” but they’re united by the world that stands against them. That becomes literal when a violent incident sends them on the lam, road-tripping to New York City and beyond, on a trail inspired by the films of Ronnie Reed (Jake Gyllenhaal), Frank’s favorite song-and-dance-man star.

With THE BRIDE!, Gyllenhaal has made a film that’s at once her very own and a feverish homage to all sorts of cinema past and present. It’s a horror story, a lovers-on-the-run movie, a crime thriller, a musical and more, and historical fealty be damned if it makes for a good scene (as when Penny and Frank sneak into a 3D movie over a decade before such features became popular). In-references are everywhere: It might just be a coincidence that the couple’s travels take them past Fredonia, NY (cf. “Freedonia” in the Marx Brothers’ DUCK SOUP), but it’s certainly no accident that the former Ida is targeted by a crime boss named Lupino, referencing the actress and pioneering filmmaker whose works included noirs and women’s-issues stories. Penny’s exploits lead legions of admiring women to adopt her look and anarchic attitude, echoing the first JOKER (while a headline calls them “Twisted Sisters”), and the use of one Irving Berlin song in a Frankensteinian context immediately recalls a classic comedic take on the property.

Whether the audience should be put in mind of a spoof at a key point in a film with different goals is another matter. At times like these, Gyllenhaal’s pastiche ambitions overtake emotional investment in the story. As strong as the two lead performances are (Bale is quite moving, conveying a great deal of soul from behind his extensive prosthetics), it’s easier to feel for them in individual scenes than during the entire course of the just-over-two-hour running time. The diversions can be entertaining, to be sure, but they also result in an uncertainty of tone. The dissonance continues straight through to the end, where the filmmaker’s choice of closing-credits song once again suggests we’re not supposed to take all this too seriously.

There’s nonetheless much to admire and enjoy about THE BRIDE!, and this kind of risk-taking by a major studio is always to be encouraged (especially considering that we’ll see how long that lasts at Warner Bros. once Paramount takes it over). Beyond the terrific work by the aforementioned actors, there’s fine support from Peter Sarsgaard and Penelope Cruz as detectives on Penny and Frank’s heels, with Sandy Powell’s lavish costumes and Hildur Guðnadóttir’s rich, varied score vital to fashioning this fully imagined world. Kudos also to makeup and prosthetics designer Nadia Stacey and to Chris Gallaher and Scott Stoddard, who did those honors on Frank, for their visceral, evocative work. Uneven as it may be, THE BRIDE! is also as alive! as any film you’ll likely see this year.

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoExclusive: DeepSeek withholds latest AI model from US chipmakers including Nvidia, sources say

-

Wisconsin4 days ago

Wisconsin4 days agoSetting sail on iceboats across a frozen lake in Wisconsin

-

Massachusetts1 week ago

Massachusetts1 week agoMother and daughter injured in Taunton house explosion

-

Maryland5 days ago

Maryland5 days agoAM showers Sunday in Maryland

-

Massachusetts3 days ago

Massachusetts3 days agoMassachusetts man awaits word from family in Iran after attacks

-

Florida5 days ago

Florida5 days agoFlorida man rescued after being stuck in shoulder-deep mud for days

-

Denver, CO1 week ago

Denver, CO1 week ago10 acres charred, 5 injured in Thornton grass fire, evacuation orders lifted

-

Oregon6 days ago

Oregon6 days ago2026 OSAA Oregon Wrestling State Championship Results And Brackets – FloWrestling