Colorado

The Water Wranglers of the West Are Struggling to Save the Colorado River

In mid-December, I drove to Lake Mead, the nation’s largest reservoir, to see its notorious bathtub ring. The tub, on this metaphor, is Lake Mead, on the border between Nevada and Arizona; the ring is a chalk-white coating of minerals that its receding waters have left behind. The Southwest, which incorporates the Colorado River Basin, has been in a protracted drought since 2000; local weather change has made it worse. “You go to Los Angeles or Denver or Las Vegas, and it doesn’t appear like an emergency, in comparison with when a hurricane slams into Florida,” John Entsminger, the overall supervisor of the Southern Nevada Water Authority, informed me just lately. “Our emergency is extra akin to sea-level rise, one thing that takes a long time to manifest, so it nearly normalizes itself.” The tub ring would be the emergency’s most seen manifestation—the drought equal of Don Lemon in a rain slicker, weathering gale-force winds in a megastorm. It serves as a every day reminder of the hundred and fifty-eight toes of water that’s not there. In response to Bob Gripentog, one of many house owners of the Lake Mead Marina, the place swarms of geese wish to overwinter, the docks hold needing to be moved farther out because the lake’s degree drops.

The day after my journey to the reservoir, the folks answerable for addressing this emergency gathered at Caesars Palace, in Las Vegas, for the annual convention of the nonprofit, nonpartisan Colorado River Water Customers Affiliation. In response to CRWUA, the Colorado River, which provides water to seven states, thirty sovereign tribes, and Mexico, is named “one of the vital regulated rivers on the earth”; the convention is the place a few of these laws get hashed out. Passersby would have seen males in sports activities coats clustered round tables, discussing desalination; jargony conferences between bureaucrats, water engineers, and utilities managers; and an expo corridor the place salesmen pitched pipe techniques to municipal officers. One group of engineers informed me that they wanted a spreadsheet to decode all of the acronyms. However beneath the trade-conference technicalities flowed an undercurrent of panic. Panelists used phrases like “determined” and “brutal” and “day of reckoning.” Within the convention’s opening remarks, Brenda Burman, the previous commissioner of the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, famous that the present drought is the worst the world has seen in twelve hundred years. There was a worse one twenty-five hundred years in the past, she added, however that didn’t appear to cheer anybody up.

This 12 months marks the centennial of the Colorado River Compact, a 1922 settlement that divvied up the river’s water between the seven basin states: California, Arizona, New Mexico, Colorado, Utah, Wyoming, and Nevada. (The unique compact talked about Native Individuals and Mexico solely in passing.) The compact’s authors hoped to create water insurance policies that might foster growth within the Southwest, and so they had been wildly profitable. Populations within the area have boomed; Phoenix, Las Vegas, Albuquerque, Denver, Salt Lake Metropolis, and Los Angeles all use Colorado River water. The river generates hydroelectric energy for hundreds of thousands of households and irrigates farms in Southern California’s Imperial Valley, the place two-thirds of the nation’s winter greens are grown.

The 1922 compact gave states the collective proper to withdraw fifteen million acre-feet of water from the Colorado every year. (One acre-foot can cowl an acre of land with one foot of water, and is sufficient to provide two or three American households for a 12 months.) However the quantity of water within the river, most of which comes from Rocky Mountain snowmelt, has traditionally been extra like twelve million acre-feet; in 2002, it was, terrifyingly, solely 3.8 million. And, as a result of states are legally entitled to attract down a dwindling useful resource, Lake Mead and its sister reservoir, Lake Powell, are approaching vital ranges. In response to the Bureau of Reclamation’s most up-to-date five-year hydrology projection, there’s a ten-per-cent probability that Lake Powell will sink to what’s referred to as minimum-power pool, the extent at which it’s going to not generate hydroelectric energy, in 2023. After minimum-power pool comes lifeless pool, a water degree so low that no water can circulation out of the dams, successfully reducing off the availability to Nevada, California, Arizona, and Mexico. In response to some current predictions, this might occur by 2025.

Throughout the previous twenty years of fierce negotiation, varied pursuits agreed to make use of much less water, however their cumulative influence was only one.3 million acre-feet per 12 months. In that point, the projections have solely grown extra dire. “Issues are taking place quicker and quicker,” Burman, who will turn out to be the overall supervisor of the Central Arizona Challenge in January, stated. “We expect we’ve acquired issues below management. We glance up six months later, and it seems we don’t.” And so, over the summer time, the Bureau of Reclamation gave Colorado River basin states a matter of months to provide you with a plan to scale back their use by a further two to 4 million acre-feet. (Some fashions name for cuts of as much as six million.) After weeks of tense conferences, the negotiations fell aside with no deal. At this 12 months’s CRWUA, lots of the identical gamers hoped to choose up the items. “I’ve been to a number of these conferences,” an attendee informed me between panels. “There’s often a number of speak about collaboration and coming collectively. They’re not likely speaking that approach anymore.”

Every water-user I met in Las Vegas appeared desirous to determine another offender for the present disaster. Cities level out that agriculture consumes eighty per cent of the Colorado’s water, whereas farmers be aware that cities continue to grow—and, by the way, producing demand for his or her winter lettuce. States that had been sorted into the Higher Basin by the 1922 compact (Colorado, New Mexico, Utah, Wyoming) argue that round three-quarters of the water is utilized by the more-populous Decrease Basin states (Arizona, Nevada, California), which in flip wish to remind everybody that, to date, they’ve lower their water use essentially the most. One speaker, from Arizona, talked about that California had, as a part of a take care of the federal authorities, just lately dedicated to conserving as much as 4 hundred thousand acre-feet per 12 months over 4 years. “That’s quite a bit for California,” he stated, which sounded to me like a neg. The farmers and the ag legal professionals had been straightforward to identify by their cowboy hats, costume boots, and normal aura of defensiveness. “Properly, I wouldn’t need to be like China, the place we are able to’t develop sufficient meals for half our inhabitants,” one stated testily once I requested him concerning the pervasive anti-ag sentiment. (He then started complaining concerning the water-guzzling gardens of San Diego.) Andy Mueller, who represents a closely agricultural district in western Colorado, stated on a panel that the agricultural neighborhood resented being branded as “evil.” “You can not deprive folks of their future by saying their lifestyle just isn’t viable,” he stated.

Theoretically, water rights are awarded on a first-come, first-served foundation. The All-American Canal, which feeds the Imperial Valley, was constructed a long time earlier than the Central Arizona Challenge, a big aqueduct system that started building within the seventies, so Southern California has senior rights. Arizona, with its junior rights, may have its water allotment lower to zero earlier than Imperial Valley farms face any cuts in any respect. The basin’s thirty sovereign tribes have their very own proper to a sure portion of the Colorado, though some have but to barter settlements that spell out simply how a lot water they’re entitled to. With the river already over-allocated, tribal water settlements are sometimes politically contentious: any water granted to them needs to be taken away from another person.

Negotiations can begin to seem to be a sport of water-rights rooster: Why shouldn’t booming Salt Lake Metropolis use the water that it’s legally entitled to, provided that Phoenix and Los Angeles as soon as developed with little regard to water shortage? Isn’t it absurd—oppressive, even—to ask tribal nations to just accept strict limits in order that water retains flowing to lands that had been stolen from them? Why ought to Arizona preserve water that may find yourself flooding an alfalfa subject, which in flip can be shipped abroad? (Alfalfa is profitable however water-intensive: in 2021, American farmers despatched a record-breaking 2.86 million metric tons overseas, largely to China and Japan; in Utah, alfalfa and hay fields swallow two-thirds of the state’s allocation of Colorado River water, however produce a fraction of 1 per cent of its gross home product.) The worry looming over CRWUA was the spectre of a “run on the river”—the liquid equal of a financial institution run. “We’re going to proceed to see this tragedy of the commons present itself as all of us proceed to behave in our personal greatest curiosity, and the higher good suffers,” Entsminger informed me.

Each state within the area has a lead water negotiator. In Nevada’s case, it’s Entsminger, who has a agency handshake, an upright bearing, and hair that’s grown progressively whiter because the water wars have escalated. Entsminger generally performs the position of truth-teller, although negotiators throughout the desk from him may model him as a nasty cop; when final summer time’s negotiations fell aside, Entsminger wrote an open letter venting his frustration, criticizing “drought profiteering proposals” and “unreasonable expectations” from water-users. “As a lot as I’m a fan of negotiating in small rooms and preserving issues confidential, I simply thought it was time for the general public at giant to appreciate that the people who find themselves presupposed to be accountable for discovering options for this river—we’re not getting it achieved,” he informed me.

Nevada has emerged as a frontrunner in water conservation, partly due to its vulnerability: the Colorado River provides ninety per cent of Las Vegas’s water, however Nevada has junior rights. Nevada’s inhabitants has grown by round seven hundred and fifty thousand folks for the reason that drought started, nevertheless it has curbed its use of Colorado River water by twenty-six per cent. The state handed laws to eradicate many grass lawns, making Las Vegas—opposite to its repute for extra—a surprisingly conservative metropolis, water-wise. Vegas residents can report the unlawful watering of a garden (as an illustration, if the water is flowing onto the sidewalk) by way of an app, and the offender will obtain a go to from an precise water cop. (Entsminger admitted that Nevada additionally has fewer competing stakeholders than a few of its neighbors: in a state with little agriculture to talk of, and just one tribe that’s entitled to water rights, “our politics begins to look actually easy.”)

I caught up with Entsminger proper after a panel of the highest water negotiators from all of the basin states. Different panels featured officers from the Bureau of Reclamation, whose presence was a reminder that the federal authorities can nonetheless step in and impose its personal cuts, a transfer that might nearly definitely encourage rapid and protracted lawsuits. Given the dire circumstances, Entsminger appeared not sure of how hopeful to be. “I nonetheless heard lots of people explaining how onerous issues are, and the way they may not have the ability to do very a lot,” he stated. Then again, he discovered a number of the backroom conversations encouraging. “We most likely had our greatest assembly of 2022 throughout the final week. However I might say that the subsequent forty days are going to inform the story of whether or not that was only a flash of optimism.”

That night, on the Percolation and Runoff Reception, a wastewater engineer gushed to me about Arizona’s progressive use of recycled effluent to brew beer—the CRWUA model of small discuss. As a singer in a sequinned costume started to croon on stage, I informed a water lawyer that lawns may begin to appear unappealing—a gross show of greed, even. “No, no, no,” he stated, with a ardour that shocked me. “Then it’s going to simply turn out to be a red-state, blue-state difficulty, which isn’t the place we would like it to go.” One of many upsides of water politics, at the least to date, is that it tends to chop throughout occasion traces. However, if it turns into a part of the tradition struggle, say goodbye to turf-removal tasks and hiya to spite lawns.

Probably the most constructive factor to come back out of CRWUA gave the impression to be that everybody was calling the disaster a disaster. That a lot was thought-about frequent floor. What to do about it, after all, continues to be an open query; forms strikes slowly, and the water is dropping quick. On my last morning at CRWUA, the espresso line was lengthy and the urns had been almost empty. The girl in entrance of me in line tilted the container so I may half-fill my cup. “Round right here, we’re good at getting the final drop,” she stated darkly.

I thought of a ship captain I met on the Lake Mead Marina. He’d spent a long time on the lake, and had personally witnessed the water ranges dropping. Final 12 months, six of the seven boat launches on the lake shut down—they had been too removed from the water to function—but the captain informed me he wasn’t nervous about it. His neighbor, he stated, was a retired intelligence operative who’d informed him that water shortages had been created by the federal government “to advertise the local weather change.” If the area ran out of water, he assured me, they might step in and repair it. He didn’t say who “they” had been, or what the repair would appear to be, however he appeared sure of 1 factor: they’d all the things below management. ♦

Colorado

Toyota Game Recap: 12/22/2024 | Colorado Avalanche

ColoradoAvalanche.com is the official Web site of the Colorado Avalanche. Colorado Avalanche and ColoradoAvalanche.com are trademarks of Colorado Avalanche, LLC. NHL, the NHL Shield, the word mark and image of the Stanley Cup and NHL Conference logos are registered trademarks of the National Hockey League. All NHL logos and marks and NHL team logos and marks as well as all other proprietary materials depicted herein are the property of the NHL and the respective NHL teams and may not be reproduced without the prior written consent of NHL Enterprises, L.P. Copyright © 1999-2024 Colorado Avalanche Hockey Team, Inc. and the National Hockey League. All Rights Reserved. NHL Stadium Series name and logo are trademarks of the National Hockey League.

Colorado

Colorado authorities shut down low-income housing developer

The Colorado Division of Securities is pursuing legal action against a man whom it claims deceived investors and used the ownership of federally supported low-income housing projects to line his own pockets.

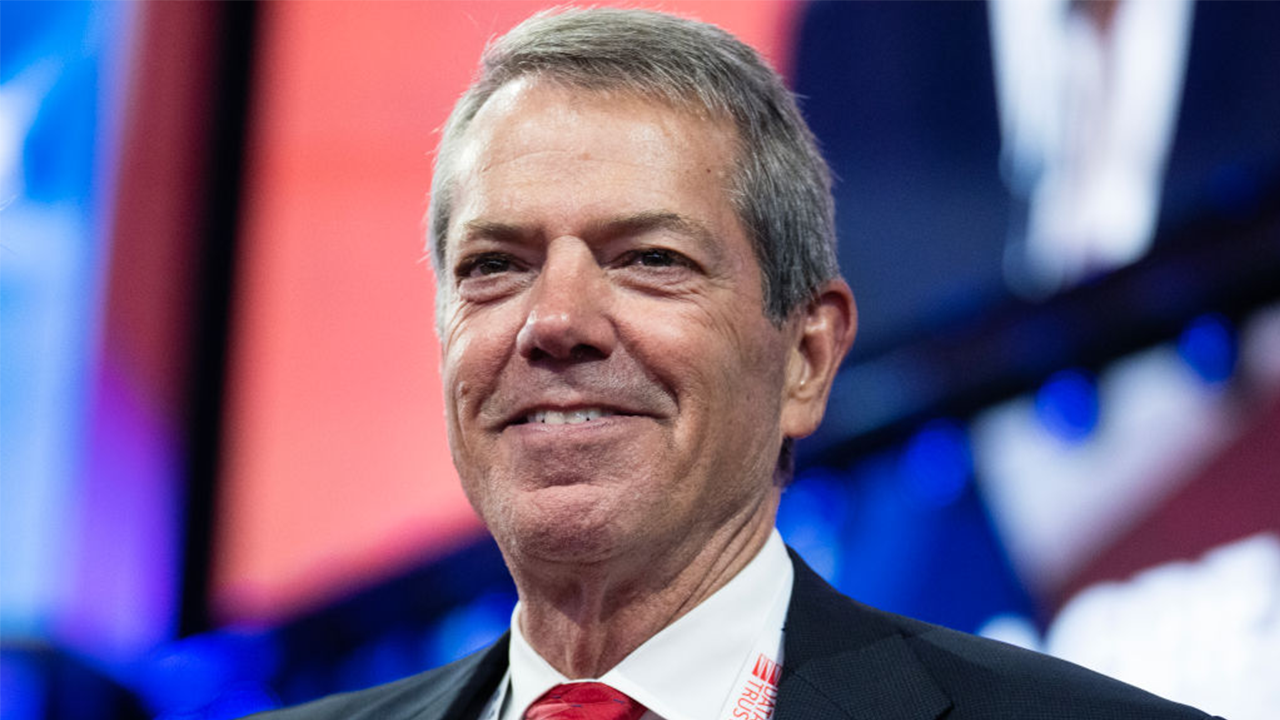

Securities Commissioner Tung Chan announced its civil court filings against Michael Dale Graham, 68, on Nov. 12.

Chan’s office filed civil fraud charges against Graham, and also asked for a temporary restraining order and freezing of Graham’s assets and his companies’. A Denver district court judge immediately granted both. Since then, two court dates to review the those orders have canceled; a third is scheduled for mid-January.

Graham operates Sebastian Partners LLC, Sebastiane Partners LLC, and Gravitas Qualified Opportunity Zone Fund I LLC (“GQOZF”), all of which were controlled by Graham during his “elaborate real estate investment scheme,” as described by the securities office in a case document.

The filing states Graham collected more than $1.1 million from eight investors to purchase three adjacent homes in Aurora. The Denver-based Gravitas fund and its investors purportedly qualified for the federal Qualified Opportunity Zone (QOZ) program with the homes. Qualified Opportunity Zones were created by the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act passed by Congress in 2017. The zones encouraged growth in low-income communities by offering tax benefits to investors, namely reductions in capital gains taxes on developed properties.

Graham formed Gravitas in early 2019 and purchased the three homes located in the 21000 block of E. 60th Avenue two years later. He quickly sold one of them with notifying investors, according to the case document. While managing the other two, Graham and Gravitas transferred the fund’s assets and never operated within QOZ guidelines to the benefit of its investors or the community, according to the state.

Gravitas also transferred the titles for the two properties to Graham privately. As their owner, Graham obtained undocumented loans from friends totaling almost $600,000. The two loans used the two properties as security.

Gravitas investors were never informed of the two loans, according to the case document. Also, Gravitas never sent its investors year-end tax reports, the securities office alleges.

Graham used the proceeds of the loans for personal use. No specific details were provided about those uses.

“Effectively, Graham used Gravitas as his personal piggy bank,” as stated in the case document, “claiming both funds and properties as his own. Graham never told investors about the risks associated with transferring title to himself. On September 1, 2023, he sent a letter to investors, stating that the properties ‘we own’ are doing well and generating growth due to record-breaking home appreciation. But Gravitas no longer owned the properties.

“Gravitas no longer had assets at all.”

Furthermore, the securities office said Graham failed to notify investors of recent court orders against him in Colorado and California. In total, Graham was ordered to pay more than $1 million in damages related to previous real estate projects.

Graham’s most recent residence is in Reno, Nev., according to an online search of public records. He evidently has previously lived in Santa Monica, Calif., and Greenwood Village.

Colorado

Colorado weather: Temperatures staying in the 60s Sunday

Watch CBS News

Be the first to know

Get browser notifications for breaking news, live events, and exclusive reporting.

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoCanadian premier threatens to cut off energy imports to US if Trump imposes tariff on country

-

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25789444/1258459915.jpg)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25789444/1258459915.jpg) Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoOpenAI cofounder Ilya Sutskever says the way AI is built is about to change

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoU.S. Supreme Court will decide if oil industry may sue to block California's zero-emissions goal

-

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25546252/STK169_Mark_Zuckerburg_CVIRGINIA_D.jpg)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25546252/STK169_Mark_Zuckerburg_CVIRGINIA_D.jpg) Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoMeta asks the US government to block OpenAI’s switch to a for-profit

-

Business1 week ago

Business1 week agoFreddie Freeman's World Series walk-off grand slam baseball sells at auction for $1.56 million

-

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23951353/STK043_VRG_Illo_N_Barclay_3_Meta.jpg)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23951353/STK043_VRG_Illo_N_Barclay_3_Meta.jpg) Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoMeta’s Instagram boss: who posted something matters more in the AI age

-

News1 week ago

East’s wintry mix could make travel dicey. And yes, that was a tornado in Calif.

-

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/24924653/236780_Google_AntiTrust_Trial_Custom_Art_CVirginia__0003_1.png)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/24924653/236780_Google_AntiTrust_Trial_Custom_Art_CVirginia__0003_1.png) Technology2 days ago

Technology2 days agoGoogle’s counteroffer to the government trying to break it up is unbundling Android apps