Alaska

Alaska Congresswoman introduces bills to protect fish, ocean ecology from trawlers

U.S. Rep. Mary Sattler Peltola, a Democrat from Alaska, introduced two bills on Wednesday that align with her long-time political, professional and personal incentives to protect marine ecosystems from industrial trawling fleets.

The Bottom Trawl Clarity Act addresses a decades-long controversy in Alaska that would require regional fishery management councils to change the regulatory definition of the “midwater” trawler’s fishing nets that have “substantial bottom contact” with the ocean floor to a more accurate definition. The current regulations allow the trawlers to fish in ecologically sensitive areas closed to bottom trawling.

“We’re very serious about it, and it’s a real bipartisan bill; it addresses a real problem with a real solution,” said the first Alaska Native to serve in Congress in an extensive interview with USA Today on May. 22.

The second bill introduces the Bycatch Mitigation Assistance Fund which would finance purchases of “camera systems, lights, and salmon excluders” for fishermen, and it is designed to help finance technology research to reduce the number of prohibited fish that are accidentally caught.

The Bycatch Reduction and Mitigation Act would fund the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Bycatch Reduction Engineering Program up to $7.5 million more than it received in 2023. The nationwide program has been funded at a five-year average of $2.28 million between 2018 and 2022.

Referencing her pro-fish election platform and a bipartisan coalition in both her 2022 and current campaigns, Peltola said, “The fact that so many Alaskans from both parties and all regions of the state rallied behind a pro-fish candidate was something that the industry took notice of, and we’ve already seen a 50% reduction in chum bycatch.

“I think that is noteworthy and that we should recognize and appreciate the industry leaders who have taken it upon themselves to reduce bycatch, added Peltola.

Peltola explains that the ones who “have the kind of resources to get the gear, equipment, and technologies that reduce the level” should be recognized as “leading by example.”

“With the other 50%, it shows that this is within reach and that this is a real [and] attainable goal, and one that we should be working towards. We should always be striving to do better when it comes to preventing waste,” added Peltola,

An industry leader issues a warning

“The bill as written could introduce a second crisis in Western Alaska communities that depend on CDQs [Community Development Quotas that direct need-based funding from fishing revenue to Western Alaska coastal communities] while favoring Seattle-based crabbing companies and pushing pollock vessels into areas of higher salmon bycatch,” said Eric Deakin, CEO, Coastal Villages Region Fund.

Presently, the trawlers are allowed to bycatch king and chum salmon and operate in areas sensitive to crab habitat. Subsistence communities and crab fishermen alike have encountered substantial fishing restrictions in recent years.

Q: Do you view the bills as a bipartisan effort?

“One hundred percent, we just got word that The Bycatch Reduction and Mitigation Act is going to have Garret Graves, a Republican from Louisiana, as a co-sponsor, as well as Jared Huffman from California as a co-sponsor.”

Q: Do you have an idea of how many specific supporters you already have on board?

“Well, I’ve got two supporters, and they’re very influential on the resources committee on both sides of the aisle. So, I think that is a very good sign, and I do really think that there is a lot of support for looking at the fisheries and how we can improve management and abundance.”

Q: How would you explain the situation in D.C. to those who would have the trawler fleets stand down or be more restricted from bycatch, and from areas known to be sensitive to crab habitat?

So this is one where I think the participation of the stakeholders is really important, and I will say that think that when of the tribes came forward and said that there holding the line and zero bycatch for Chinook salmon, that really was the tribes who came up with that, and it’s more on principle. Native people have a real, and I don’t even really know how to explain it, we have such an aversion to wasting and not [for] sharing. The worst thing you can do is waste food. We really feel strongly that the food that we eat, the animals and fish and birds that we eat, those animals, fish and birds knowingly gave themselves to the hunter or fisherman because they witnessed that they are responsible with their catches.

When we’re irresponsible with our catches, bad things happen; this is one of the foundational tenets of most native culture, because salmon is very present in our mind and salmon and has happened in our elders’ lifetimes. We are very conscientious about salmon. The smallest little change could result in disaster for many native people over history.

So one of the most important things for native people is the most important kind of guiding moral compass principle, [it] is this idea of not wasting anything, and the fact that we have metric tons of juvenile salmon, halibut crab have been discarded every year for 30 years. It’s very disturbing, and many people feel like this is because of that 30 years of metric tons being wasted, and that that’s why we’re in this predicament.

Crab fishermen have many concerns about these sensitive areas, and the other thing I want to say is we have so much more research that needs to be done. I’ve spoken with crab fishermen in Kodiak who really believe that a lot of the surveys are incomplete, or they are too small of a snapshot.

My personal belief is at the federal level, we have got to get much more serious about surveys and research. During the [U.S. Senator] Ted Stevens’s years, he invested a lot of money in research, and over the years, that has diminished and been siphoned off to other states. The administration has interpreted those funds [as] that they need to be … prioritized for treaty tribes or the funding to be prioritized to endangered stocks, which puts Alaska at a real disadvantage.

If half of the world’s seafood comes from Alaska, we should be investing so much more money in surveys and research. There’s so much that we do not know, we do not understand, and we need to understand better, especially with this paradigm change. So, I just really want the federal government to start investing in a real way.

When it comes to specific numbers, I think this is something that the stakeholders really need to have a robust discussion about.

Q: Has there been any correspondence with the Biden Administration about updating the National Standards of the Magnuson-Stevens Act?

We have heard that they have been looking at those three national standards that we’re pushing them to help define, and I like to call it the ABCs of the standards: So, its ‘allocation, bycatch and communities.’ We understand that they are working on those rules, and the proposal may come out in June, but we have not been given any heads-up on what they’re working on and what those may look like.

The MSA National Standard Four says that ‘allocations of fishing privileges should be distributed so no corporation acquires an excessive share of such privilege.’

Q: Has enforcement and recognition of this standard concerning the largely Seattle-based pollock fleets been improved and can it be further improved?

I don’t think we’re meeting that definition, and I think that is a time that we revisit the national standard and see that we’re meeting the mark. I think many Alaskans would feel that we’re not meeting the mark on a number four.

[Reporter’s note:] The MSA National Standard Eight says negative economic impacts on communities should be minimized ‘to the extent practicable.’

Q: Has enforcement and recognition of this standard concerning the largely Seattle-based pollock fleets been improved and can it be further improved?

I think we have a lot of room to grow on this one, and this is one where I think it’s important that we define ‘practicable.’ That is one thing that many Alaskans have expressed concern about, because it tends to be an arbitrary definition. Any user-group could say, ‘well that’s not practicable.’ So that makes it a really challenging rule to get your arms around. What is practicable and what isn’t practicable? And if there’s a 1% drop in earnings, and I think that’s where a lot of folks are saying, ‘Well that’s not practicable because then we’ll lose money.’

We are seeing significant impacts to communities, and one of the other concerns I have with number eight is just the definition of community itself. We find in the AP [House Appropriations] subcommittee where members of the AP were advancing this idea that industrial factory trawlers are a community. This concerns me a great deal because my definition of a community tends to be more of, say, a Yukon River village that’s been in that location for about 12,000 years, and it’s located there because of its dependence [on salmon] and because of its relationship with salmon and understanding that the salmon will return every year.

That, to me, is a community that has been there and has shown, a reliance and independence and a relationship with marine resources versus an industrial factory trawler that really came about in the 1990s or 1980s or, you know, much, much more recently in any way than 12,000 years.

Alaska

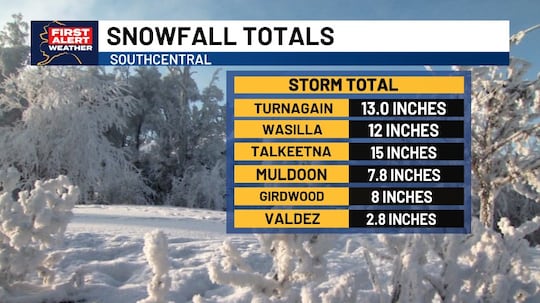

Dozens of vehicle accidents reported, Anchorage after-school activities canceled, as snowfall buries Southcentral Alaska

ANCHORAGE, Alaska (KTUU) – Up to a foot of snow has fallen in areas across Southcentral as of Tuesday, with more expected into Wednesday morning.

All sports and after-school activities — except high school basketball and hockey activities — were canceled Tuesday for the Anchorage School District. The decision was made to allow crews to clear school parking lots and manage traffic for snow removal, district officials said.

“These efforts are critical to ensuring schools can safely remain open [Wednesday],” ASD said in a statement.

The Anchorage Police Department’s accident count for the past two days shows there have been 55 car accidents since Monday, as of 9:45 a.m. Tuesday. In addition, there have been 86 vehicles in distress reported by the department.

The snowfall — which has brought up to 13 inches along areas of Turnagain Arm and 12 inches in Wasilla — is expected to continue Tuesday, according to latest forecast models. Numerous winter weather alerts are in effect, and inland areas of Southcentral could see winds up to 25 mph, with coastal areas potentially seeing winds over 45 mph.

Some areas of Southcentral could see more than 20 inches of snowfall by Wednesday, with the Anchorage and Eagle River Hillsides, as well as the foothills of the Talkeetna Mountain, among the areas seeing the most snowfall.

See a spelling or grammar error? Report it to web@ktuu.com

Copyright 2026 KTUU. All rights reserved.

Alaska

Yundt Served: Formal Charges Submitted to Alaska Republican Party, Asks for Party Sanction and Censure of Senator Rob Yundt

On January 3, 2026, Districts 27 and 28 of the Alaska Republican Party received formal charges against Senator Rob Yundt pursuant to Article VII of the Alaska Republican Party Rules.

According to the Alaska Republican Party Rules: “Any candidate or elected official may be sanctioned or censured for any of the following

reasons:

(a) Failure to follow the Party Platform.

(b) Engagement in any activities prohibited by or contrary to these rules or RNC Rules.

(c) Failure to carry out or perform the duties of their office.

(d) Engaging in prohibited discrimination.

(e) Forming a majority caucus in which non-Republicans are at least 1/3 or more of the

coalition.

(f) Engaging in other activities that may be reasonably assessed as bringing dishonor to

the ARP, such as commission of a serious crime.”

Party Rules require the signatures of at least 3 registered Republican constituents for official charges to be filed. The formal charges were signed by registered Republican voters and District N constitutions Jerad McClure, Thomas W. Oels, Janice M. Norman, and Manda Gershon.

Yundt is charged with “failure to adhere and uphold the Alaska Republican Party Platform” and “engaging in conduct contrary to the principles and priorities of the Alaska Republican Party Rules.” The constituents request: “Senator Rob Yundt be provided proper notice of the charges and a full and fair opportunity to respond; and that, upon a finding by the required two-thirds (2/3) vote of the District Committees that the charges are valid, the Committees impose the maximum sanctions authorized under Article VII.”

If the Party finds Yundt guilty of the charges, Yundt may be disciplined with formal censure by the Alaska Republican Party, declaration of ineligibility for Party endorsement, withdrawal of political support, prohibition from participating in certain Party activities, and official and public declaration that Yundt’s conduct and voting record contradict the Party’s values and priorities.

Reasons for the charges are based on Yundt’s active support of House Bill 57, Senate Bill 113, and Senate Bill 92. Constituents who filed the charges argue that HB 57 opposes the Alaska Republican Party Platform by “expanding government surveillance and dramatically increasing education spending;” that SB 113 opposes the Party’s Platform by “impos[ing] new tax burdens on Alaskan consumers and small businesses;” and that SB 92 opposes the Party by “proposing a targeted 9.2% tax on major private-sector energy producer supplying natural gas to Southcentral Alaska.” Although the filed charges state that SB 92 proposes a 9.2% tax, the bill actually proposes a 9.4% tax on income from oil and gas production and transportation.

Many Alaskan conservatives have expressed frustration with Senator Yundt’s legislative decisions. Some, like Marcy Sowers, consider Yundt more like “a tax-loving social justice warrior” than a conservative.

Related

Alaska

Pilot of Alaska flight that lost door plug over Portland sues Boeing, claims company blamed him

The Alaska Airlines captain who piloted the Boeing 737 Max that lost a door plug over Portland two years ago is suing the plane’s manufacturer, alleging that the company has tried to shift blame to him to shield its own negligence.

The $10 million suit — filed in Multnomah County Circuit Court on Tuesday on behalf of captain Brandon Fisher — stems from the dramatic Jan. 5, 2024 mid-air depressurization of Flight 1282, when a door plug in the 26th row flew off six minutes after take off, creating a 2-by-4-foot hole in the plane that forced Fisher and co-pilot Emily Wiprud to perform an emergency landing back at PDX.

None of the 171 passengers or six crew members on board was seriously injured, but some aviation medical experts said that the consequences could have been “catastrophic” had the incident happened at a higher altitude.

Fisher’s lawsuit is the latest in a series filed against Boeing, including dozens from Flight 1282 passengers. It also names Spirit AeroSystems, a subcontractor that worked on the plane.

The lawsuit blames the incident on quality control issues with the door plug. It argues that Boeing caught five misinstalled rivets in the panel, and that Spirit employees painted over the rivets instead of reinstalling them correctly. Boeing inspectors caught the discrepancy again, the complaint alleges, but when employees finally reopened the panel to fix the rivets, they didn’t reattach four bolts that secured the door panel.

The complaint’s allegations that Boeing employees failed to secure the bolts is in line with a National Transportation Safety Board investigation that came to the conclusion that the bolts hadn’t been replaced.

Despite these internal issues, Fisher claims Boeing deliberately shifted blame towards him and his first officer.

Lawyers for Boeing in an earlier lawsuit wrote that the company wasn’t responsible for the incident because the plane had been “improperly maintained or misused by persons and/or entities other than Boeing.”

Fisher’s complaint alleges that the company’s statement was intended to “paint him as the scapegoat for Boeing’s numerous failures.”

“Instead of praising Captain Fisher’s bravery, Boeing inexplicably impugned the reputations of the pilots,” the lawsuit says.

As a result, Fisher has been scrutinized for his role in the incident, the lawsuit alleges, and named in two lawsuits by passengers.

Spokespeople for Boeing and Spirit AeroSystems declined to comment on the lawsuit.

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoHamas builds new terror regime in Gaza, recruiting teens amid problematic election

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoFor those who help the poor, 2025 goes down as a year of chaos

-

Business1 week ago

Business1 week agoInstacart ends AI pricing test that charged shoppers different prices for the same items

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoPodcast: The 2025 EU-US relationship explained simply

-

Business1 week ago

Business1 week agoApple, Google and others tell some foreign employees to avoid traveling out of the country

-

Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoChatGPT’s GPT-5.2 is here, and it feels rushed

-

Health1 week ago

Health1 week agoDid holiday stress wreak havoc on your gut? Doctors say 6 simple tips can help

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week ago‘Unlucky’ Honduran woman arrested after allegedly running red light and crashing into ICE vehicle