Sports

'It will change your life.' Ultramarathon runners embrace pain of Western States 100

AUBURN, Calif. — The Western States Endurance Run isn’t so much a race as it is torture, spooled out slowly and sadistically over 100 miles. It’s a test of willpower, fortitude and pain tolerance more than a measure of stamina, speed or athletic talent.

It is also, one might add, a test of sanity.

Yet so many people want to attempt the world’s oldest 100-mile race, which turned 50 last weekend, that organizers use a lottery each year to wean the nearly 10,000 applicants down to a field of 375.

Spectators stand on the mountain before sunrise as they wait for runners to climb out of Olympic Valley, Calif., during the first four miles of the Western States 100 ultramarathon on June 29.

The California course begins in Olympic Valley, site of the 1960 Winter Games, and finishes in tiny Auburn, a former mining town and railroad hub in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada mountains. Along the way it climbs nearly three miles up steep, craggy points and plunges more than four miles down narrow canyons. The course is so challenging, calling it a run is more aspirational than factual since all but the fastest racers hike about 20 of the 100 miles.

“It’s the legends, it’s the history, it’s the stories that spread out over more than 50 years that make Western States really, really special,” said John Trent, a former sportswriter and Western States board member who has finished the race 11 times.

“It will change your life. It’ll change the way you view yourself and, more importantly, the way you view others.”

Because ultramarathons — any race longer than the traditional 26.2-mile marathon distance — are as egalitarian as they are fatiguing, aside from the trophy given to the top male and female runners and a few age-group awards, everyone who finishes Western States in less than 30 hours gets the same handmade belt buckle, in either silver or bronze. They’ve become the most prestigious finisher’s prize in the sport.

But that’s not why people run.

“You’re racing against yourself, seeing what you’re capable of doing,” said William Shaw, a 52-year-old from Georgia who ran the race for the first time last weekend. “It’s amazing.”

1

2

3

1. A runner casts a long shadow as he runs west out of Michigan Bluff during competition in the Western States 100 on June 29 in Auburn, Calif. 2. Aid station volunteers cool off Cole Watson during a stop at the Devil’s Thumb aid station. 3. Runner Tyler Green crosses the Middle Fork of the American River at Rucky Chucky.

And when you’ve shown what you’re capable of doing, you come back to do it again. That’s why Luanne Park returned to Olympic Valley after an 11-year absence to run the race for the 13th time.

At 63, Park, a retired art teacher from Mt. Shasta, doesn’t need another belt buckle; she’s already won 10 and given most of them away. Nor does she have anything left to prove. A former world-class triathlete who ran in the first U.S. Olympic trials in the women’s marathon, Park has run 166 ultramarathons, finishing as high as second at Western States and once completing the course in less than 20 hours.

“It’s like, ‘What can the human body do when you treat it nice?’ I want to see what my potential is at this stage,” Park said. “I can still challenge myself. I just happen to have gray hair now and some wrinkles.”

Luanne Park, right, hikes over Cougar Rock during the 2024 Western States 100.

Her support crew, the people who met her at the aid stations along the course to refill her water bottles, provide her with mashed potatoes, turkey wraps, pudding and Ensure and bathe her in ice, featured women from different stages of her life.

There was Renee Thomas, her wife and partner of 37 years and a former triathlete; Linda McGuire, a childhood friend from Chico and a former winemaker whose father ran Western States in 1986; Donna Riddell, Park’s best friend from her Mt. Shasta years; and Annie Phillips, her college roommate and track teammate at Oregon State.

“It’s something she wanted to do for so long but she knows, logistically, that this is the end of competing on this level,” Thomas said the night before the race over a pasta dinner in the home the women rented for the race. “She is kind of preparing herself that, ‘I’ve just got to be OK with whatever happens.’”

But she wasn’t OK. Park began the race battling neuropathy that left her feet, hands and legs numb; depression that made it difficult to train; and circulation issues that forced her to run in knee-high compression socks.

And with the word “Persevere” tattooed on one arm.

1

2

3

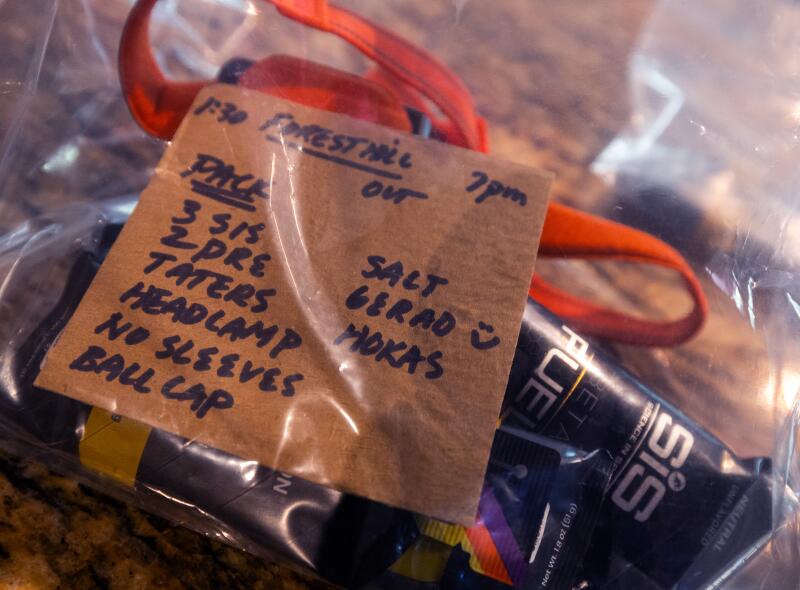

1. Luanne Park prepares her running shoes the night before competition in the Western States 100 on June 28 in Olympic Valley, Calif. 2. Luanne Park prepared items for an aid station drop the night before competition in the Western States 100 June 28 in Olympic Valley, Calif. 3. Luanne Park, center, is toasted during dinner with her support team the night before competition in the Western States 100 on June 28 in Olympic Valley, Calif.

“It’s a paralyzing thought of having to stand on that starting line knowing that my body’s not nearly at 100%,” she said. “This race is a huge question mark. Whatever that time is when I cross the fire line, that needs to be good enough.

“It is scary.”

After waiting 11 years for her lottery number to come up, giving her a spot in the race, there was never any doubt she would run. Nor, in her mind, was there any doubt she would finish. In fact, only two of the 375 people who stepped to the starting line had finished more Western States than Park.

“Every one of us that was at that starting line June 29, this was our Olympics,” Park said.

Western States is among the best-known ultramarathons in the world, though it was born mostly by accident.

For 19 years, equestrians rode the 100-mile trail from Olympic Valley to Auburn, often finishing in about half a day. But the course was considered far too long and rugged for someone to cover on foot in less than 24 hours.

It was “universal opinion” that it was “beyond the powers of human endurance” to cover 100 miles of rough mountainous trail on foot that quickly, insisted Wendell Robie, who organized the Western States Trail Ride.

Top, Shannon Krogsrud, 35, of Auburn, has a big smile after climbing four miles out of Olympic Valley during the Western States 100 on June 29. Bottom, Daniel Jones climbs out of a canyon to the Devil’s Thumb aid station during the Western States 100 on June 29.

Robie was proved wrong within days of making that statement, and Gordy Ainsleigh, a 27-year-old woodcutter, novice horseback rider and former high school cross-country runner, was the unlikely mythbuster.

Until the morning of Aug. 3, 1974, Ainsleigh’s greatest competitive achievement had been winning the Sierra College pancake-eating tournament. Large and athletic with a neat beard and a mane of blond hair that fell to his shoulders, Ainsleigh rode in the trail race a couple of times, but because of his size, he had to dismount and walk much of the course alongside his horse.

When his horse went lame, preventing him from finishing the 1973 race, another rider jokingly urged him to compete the next year without a steed since he usually spent more time on foot than in the saddle.

Ainsleigh accepted the challenge and, wearing shorts and a white Western State Trail Ride T-shirt, he set off just before dawn. He finished before the next sunrise, arriving in Auburn in 23 hours 42 minutes, doing a series of cartwheels at the finish.

A runner heads west out of Michigan Bluff during competition in the Western States 100 on June 29 in Auburn, Calif.

It wasn’t exactly Roger Bannister breaking four minutes in the mile, but a barrier had fallen just the same — especially for Ainsleigh, who went on to become a chiropractor, second-degree black belt in karate and an elite rock climber.

“It was a real turning point in my life,” he said years later. “It occurred to me that maybe there were a whole bunch of other things I thought I couldn’t do.”

Runners cross the steep trail climbing out of Olympic Valley during the first four miles of the Western States 100 on June 29.

Ainsleigh, who still competes in ultras at 77, ran Western States for the 22nd and final time in 2007. He finished 12 of those races in less than 24 hours. And the race he gave birth to became so popular, a record 9,388 runners completed a 100-kilometer or 100-mile trail qualifying race with names like Cruel Jewel, Worlds End and the Georgia Death Race and promised to pay a $450 entry fee before entering the lottery for one of the coveted spots at the starting line. That arduous screening process is one reason Western States has had relatively few serious injuries and no deaths in 50 years.

If you win the lottery, you also get a cheery participant guide that warns of renal shutdown, heat stroke, hypothermia, altitude sickness, poison oak and bears, among other things. Nearly 300 starters in this year’s race were running it for the first time and their reward started with a lung-crushing, 4½-mile climb from the ski resort at Olympic Valley to Emigrant Pass, more than a mile and a half above sea level.

Making the 2,550-foot ascent to the pass is a significant achievement. Yet the Western States runners still have more than 96 miles to go.

The trail covers some of the most scenic and unforgiving terrain in North America, following a narrow path past granite clefts and through forests of towering Ponderosa pines, fir, cedar and oak trees. Native Americans trekked the same path for thousands of years to hunt, fish and forage for food. Then in the middle of the 19th century, when gold and silver mines popped up in the area, the Western States Trail became the main highway for transporting mining equipment and other essentials over the mountain peaks and into the steep canyons.

Runner Daniel Jones crosses the Middle Fork of the American River at Rucky Chucky during the Western States 100 on June 29 in Auburn, Calif.

“The course is so different from top to the bottom,” Park said. “It’s like going through different time zones. You’re definitely going through different environments.”

This year’s race began in 48-degree temperatures, just as the sun began peeking over the mountains. But by the time Park made it to Robinson Flat, the first major aid station, it was 26 degrees warmer and a blazing sun was shining down from a cloudless sky.

It took her 7 hours 50 minutes to cover the first 30.3 miles, leaving her more than 80 minutes behind schedule to finish within 24 hours. That was the least of her problems, though, because when Park entered the aid station, she headed straight for the medical tent, dropping listlessly into a folding chair.

Spectators use headlamps to guide the way out of Olympic Valley during the Western States 100 on June 29.

Park’s pulse was racing at 170, while her blood pressure was a weak 90 over 60. As she downed water and two containers of pickle juice in an effort to hydrate, medics considered whether to let her continue. After 14 long minutes, she was allowed to join Thomas and the rest of her crew, who helped her change shoes, refill her water bottles and drop cubes of ice inside her singlet.

“I’m OK,” said Park, a slight, intense woman whose dark tan and close-cropped hair leave her looking at least a decade younger than the age on her driver’s license. “I’m doing this for myself. I don’t really care what my time is. If they want to pull me [out], they can pull me. But they’re going to have to pull me.

“I’m running with my heart now and not my head.”

Park’s prerace plan called for her to spend no more than two minutes in each of the 19 aid stations, small pop-up cities of vinyl canopies and folding tables where some of the race’s 1,600 volunteers hand out water, ice, snacks, energy bars, gels and a wide array of food. Yet she had been forced to spend almost 20 minutes at Robinson Flat before finally shuffling down the narrow, rocky path toward Michigan Bluff, the next major aid stop 25 miles away.

The course plunged more than 4,000 feet over the next 16 miles and that helped Park pass about two dozen runners, leaving her first in her age group and getting her back within striking distance of 24-hour pace. But the lack of snowfall on the course exposed roots and left the trail unusually rocky, causing Park to fall three times, leaving her bare legs and white singlet torn and covered in dirt.

A runner heads west out of Michigan Bluff during the Western States 100 on June 29 in Auburn, Calif.

Making things even more difficult was the fact the course was on fire. The Creek Fire broke out in mid-afternoon, forcing evacuations at the west end of the trail, leaving the air smoky and briefly preventing support crews from accessing the two aid stations at either side of the American River, 22 miles from the finish.

Park’s crew, unaware of her struggles, followed her progress on their cellphones from beneath an E-Z Up canopy at Michigan Bluff. Then, suddenly, Park disappeared from the tracking app at a point where the course makes a steep climb. The crew’s mood shifted quickly from positive to panic before Park, in tears, called from a cellphone.

Her race, she said, was over, her head having won out over her heart. Still, it took another two hours before she allowed a race official to cut off her race wristband, officially signaling her withdrawal.

“I started thinking about my crew, all the support people, my sponsor and thinking ‘Ohmigod, I’ve got to do it,’” she said. “Then I thought, ‘You know what? This one time in my life I’m going to do something without thinking of other people’ and that led me to drop. It was like, ‘This is totally for me,’ which seems like a weird thing.”

She had been forced to hike many of the 47 miles she covered and she knew the route well enough to know that several significant climbs, a river crossing and punishing plunges to the canyon floors lay ahead.

Luanne Park, right, hugs Renee Thomas, her wife and partner of 37 years, after dropping out of the Western States 100.

Park wasn’t the only runner the trail beat that day; nearly a quarter of the field failed to make it to the finish.

Hours later Phillips, who spent much of the weekend looking for cosmic meaning in random events, told Park she interpreted her progress through the canyons as a sign.

“Yeah,” Park replied drolly. “A stop sign.”

After climbing and descending more than 40,000 feet — an elevation change more than two miles greater than Mt. Everest is tall — Western States finishes on the pool-table-flat red synthetic running track at Placer High School.

Just getting there, as Park can attest, is a victory. And the 286 who made it this year got the same kind of handcrafted belt buckle Ainsleigh received 50 years ago.

Front-runner Jim Walmsley is the center of attention as his crew tends to cooling and hydration during a stop at the Michigan Bluff aid station during the Western States 100 on June 29 in Michigan Bluff, Calif. Walmsley won the race with a time of 14:13:45.

Front-runner Jim Walmsley rests his blistered feet during a stop at the Michigan Bluff aid station on June 29 in Auburn, Calif.

Four-time champion Jim Walmsley of Flagstaff, Ariz., was the first across the line in 14 hours 13 minutes 45 seconds, winning by nearly 11 minutes. He owns the course’s fastest finish.

Katie Schide of Gardiner, Maine, successfully defended her title in the women’s race, running 15:46:57, 17 minutes off the course record. Both winners finished before dark, but the real drama didn’t begin until the next sunrise. To win the coveted silver belt buckle, runners must finish in 24 hours; finish in 30 hours and you get a bronze one.

Miss that by a second though and, officially, you didn’t finish at all.

The rules have conspired to set up the “golden hour,” one of the most emotional and inspiring traditions in running. Sixty-one finishers, about 22%, crossed the line in final hour this year and thousands of locals, along with runners and their crews, packed the grandstands, set up picnic lunches on the football field and lined the track at Placer High, ringing cow bells and cheering them on.

Water drips from front-runner Jim Walmsley’s cap during a stop at the Michigan Bluff aid station on June 29 in Auburn, Calif. Walmsley won the race with a time of 14:13:45.

“It becomes a matter of survival and just moving,” Trent said. “As long as you keep moving, you have a shot.”

For some, the respect and adulation of the final minutes on the track make it all worthwhile. But that’s also where the toll of the Western States 100 becomes real. Once-fluid runners hobble stiff-legged to the finish, while others list awkwardly to one side. Some grab at sore hips or hamstrings while others finish with bruised, bloodied and blackened limbs after taking falls on the trail.

“Never again,” said Emily Clay, a 34-year-old from Baltimore who has biked across the country but never run 100 miles in a single stretch.

Nearby Shaw, the 52-year-old Georgian, sat alone on a bench, head in hand, staring blankly at a half-eaten hamburger. He was completely drained after finishing 37 minutes before the 30-hour cutoff and 10 minutes ahead of Clay. The race, he said, was the hardest thing he has ever done.

“Absolutely. But it’s a whole lot of fun too. It’s too fun,” he said.

Sam Fiandaca, 52, of Foresthill is greeted by fans crowding the Placer High School track infield to cheer on runners as they finish the Western States 100 ultramarathon on June 30 in Auburn, Calif.

When Chris Culpepper, a 59-year-old from Houston, hit the track he doubled over in pain and with less 100 yards of the 100-mile race remaining, he simply stopped. He could see the finish line; he could probably throw a rock across it. But he couldn’t make it there on foot.

Then the crowd came to its feet, and with shouts of “Chris!” ringing in his ears, Culpepper resumed his slow shuffle, reaching the finish line with fewer than nine minutes to spare.

Seven others followed him; the last was Iris Cooper, a 65-year-old Canadian and veteran of more than 100 ultras, who was the final official finisher — and the oldest woman finisher — in 29:56.10.

But she wasn’t the last runner on the track. Mill Valley’s Will Barkan, bidding to become the first legally blind runner to finish Western States, entered the stadium with less than a minute left on the clock, then crossed the line 33 seconds after the 30-hour cutoff.

As he stumbled to a stop next to his fiancee, Kim, Barkan, carrying a plastic water bottle and wearing a red T-shirt over a long-sleeve white shirt caked with dirt and blood, he asked “Did I make it?”

“No,” came the reply.

Barkan had run through the smoke of a wildfire, fallen numerous times, stubbed his toes until his shoes filled with blood and battled a sore knee. But he was 33 seconds too late to make any of that count. The official results do not include his name.

Yuki Naotori, 51, of Fukuoka Japan, kneels on the track at Placer High after crossing the finish line in the Western States 100 Sunday, June 30, 2024 in Auburn, CA.

Yet Barkan, like Park and every other runner who has stepped to the Western States starting line, did so looking not for glory, fame or even a belt buckle. The race was never about any of that. When Ainsleigh ran the trail for the first time 50 years ago, he was running simply to prove he could do it. Everyone who has followed ran to prove the same thing.

So while hours may have separated Barkan from the trophy Walmsley received and seconds may have separated him from a bronze belt buckle, he didn’t leave the track at Placer High empty-handed. Or even disappointed.

He left it the way every Western States runner does — as a champion.

“It’s a rare honor to be here,” he told reporters. “I feel super lucky I got a chance.”

Sports

Olympic medalist suffers serious injuries after ‘death-defying’ skateboarding stunt

NEWYou can now listen to Fox News articles!

An Olympic medalist and 13-time X Games winner suffered serious head injuries after a stunt went wrong.

Nyjah Huston, who won bronze in Paris in 2024, said he suffered a fractured skull and eye socket.

“A harsh reminder how death-defying skating massive rails can be…” Huston wrote in an Instagram post which included a photo of himself in a hospital bed. “Taking it one day at a time. I hope yall had a better new years then me. We live to fight another day.”

Nyjah Huston of the United States competes in the men’s street prelims during the Paris 2024 Olympic Summer Games at La Concorde 3. (Jack Gruber/USA TODAY Sports)

The post also featured Huston being treated by first responders and friends, along with another photo showing a large black-and-blue mark on Huston’s eye.

Numerous skating legends showed their support for Huston, who is considered one of the best skateboarders in the United States today.

Nyjah Huston of Team USA reacts at the Skateboarding Men’s Street Prelims on day two of the Tokyo 2020 Olympic Games at Ariake Urban Sports Park on July 25, 2021, in Tokyo, Japan. (Dan Mullan/Getty Images)

BROCK PURDY SAYS 49ERS HAVE A ‘CHIP ON THEIR SHOULDER’ ENTERING PLAYOFFS AFTER MISSING LAST SEASON

“Been watching @nyjah grow up into one of the best skaters to ever do it and it amazes me the amount of grit this kid has,” Shaun White shared on his Instagram story, via Pro Football Network. “You got this brother. Heal quick!”

Even Tony Hawk shared well-wishes on Huston’s Instagram post.

“Heavy. Stay strong; we know you’ll be back,” the skateboarding legend wrote.

“Man.. prayers for healing brother!” added Ryan Sheckler.

It is unknown whether Huston was wearing a helmet at the time of the incident.

Nyjah Huston, of the United States, celebrates during the men’s skateboard street final at the 2024 Summer Olympics, Monday, July 29, 2024, in Paris, France. (AP Photo/Frank Franklin II)

Huston has seven gold medals and five silvers in world championships. He has not competed since the 2024 Olympics, but the California native has his eyes set on the 2028 Games in Los Angeles.

Follow Fox News Digital’s sports coverage on X, and subscribe to the Fox News Sports Huddle newsletter.

Sports

Prep talk: JuJu Watkins returns to Sierra Canyon on Friday

JuJu Watkins is returning to Sierra Canyon High on Friday, the place where she was a high school basketball All-American.

The school will hold a ceremony retiring her jersey at halftime of the boys’ basketball game between Sierra Canyon and Sherman Oaks Notre Dame.

She will be presented with a framed jersey.

Watkins is sitting out this season at USC while recovering from a knee injury.

Sierra Canyon girls’ basketball coach Alicia Komaki said, “She raised our standards, which was hard to do because we had won four state championships. She was an incredibly talented player.”

Watkins was also making a huge impact in the college game until her injury last season during the NCAA playoffs.

This is a daily look at the positive happenings in high school sports. To submit any news, please email eric.sondheimer@latimes.com.

Sports

Miami beats Ole Miss behind Carson Beck’s game-winning touchdown to reach CFP National Championship Game

NEWYou can now listen to Fox News articles!

The Miami Hurricanes are heading to the College Football Playoff National Championship Game, coming away with a narrow victory over Ole Miss, 31-27, in an all-time postseason contest.

The Hurricanes will now await the winner of the other semifinal between the Indiana Hoosiers and Oregon Ducks to see who they will play on Jan. 19. But Miami will do so on their home turf, with the National Championship Game being played at Hard Rock Stadium – the site of their home games.

The game began slowly for both teams, with only Miami getting on the scoreboard in the first quarter with a field goal on their 13-play opening drive. But the fireworks came out from there for the Rebels thanks to the speed of running back Kewan Lacy.

CLICK HERE FOR MORE SPORTS COVERAGE ON FOXNEWS.COM

Charmar Brown of the Miami (FL) Hurricanes celebrates a run in the first quarter of the 2025 College Football Playoff Semifinal at State Farm Stadium on Jan. 8, 2026 in Glendale, Arizona. (Steve Limentani/ISI Photos)

On just the second play of the second quarter, Lacy was off to the race, finding a seam and busting out a 73-yard touchdown run to go up 7-3 after the extra point.

But this game was back and forth for quite some time, including the ensuing Hurricanes drive as quarterback Carson Beck led the way on a 15-play touchdown series with a CharMar Brown rushing score from four yards out.

The game was deadlocked at 10 apiece when Beck decided to air it out to Keelan Marion, and it was worth the risk. Marion made the grab for a 52-yard touchdown to help Miami go up 17-13 at halftime.

CFP: WHAT DO CIGNETTI, LANNING, CRISTOBAL AND GOLDING HAVE IN COMMON? NICK SABAN

The third quarter was an odd one for both squads, as their opening drives resulted in a missed field goal apiece. Then, after Beck threw an interception, the Rebels were able to cut the lead to 17-16 in favor of the Hurricanes heading into the fourth quarter for the ages.

There was no absence of electric plays when it mattered most in the final 15 minutes, as Rebels quarterback Trinidad Chambliss got his team downfield enough to take a 19-17 lead with a field goal.

But the speed of Malachi Toney changed the scoreboard for Miami in the best way possible, as he took a screen 36 yards to the house, capping a four-play, 75-yard answer drive for the Hurricanes right after Ole Miss took the lead.

Trinidad Chambliss of the Ole Miss Rebels celebrates a touchdown against the Miami Hurricanes in the second quarter during the 2025 College Football Playoff Semifinal at the VRBO Fiesta Bowl at State Farm Stadium on Jan. 8, 2026 in Glendale, Arizona. (Ronald Martinez/Getty Images)

With a 24-19 lead and five minutes left to play in the game, Chambliss and the Rebels’ offense had quite enough time to retake the lead. He did just that, finding trusty tight end Dae’Quan Wright for 24 yards to send the Rebels faithful ballistic.

Ole Miss wanted to go for two in hopes of making it a three-point lead, and Chambliss came through again, finding a wide open Caleb Odom for the key score.

It was up to Beck and the Miami offense to keep the game alive with at least tying the game at 27 apiece. On a crucial third-and-10 just inside field goal range, Beck was confident with his pass to Marion to get well within range. Another pass to Marion made it first-and-goal, and it was clear Miami wasn’t trying to force overtime. They wanted to win it all.

How fitting was it that Beck, scanning the field, found a seam to his left and just sprinted for the colored paint to score the game-winner with 18 seconds left.

But things got fascinating at the end, with Ole Miss going 40 yards in just a few seconds to set up a Hail Mary for the win. Chambliss had the space to loft a pass to the end zone, and though it hit off the hand of a teammate, it landed incomplete for the Miami victory.

Carson Beck of the Miami Hurricanes passes the ball against the Ole Miss Rebels in the first quarter during the 2025 College Football Playoff Semifinal at the VRBO Fiesta Bowl at State Farm Stadium on Jan. 8, 2026 in Glendale, Arizona. (Chris Coduto/Getty Images)

In the box score, Beck was 23-of-37 for 268 yards with his two passing touchdowns and an interception. Marion was a key player in the victory with seven catches for 114 yards, while Mark Fletcher Jr. set the tone in the ground game with 133 yards rushing on 22 carries. Toney also tallied 81 receiving yards for Miami.

For Ole Miss, Chambliss also went 23-of-37 for 277 yards with his touchdown to Wright, who finished with 64 yards on three grabs. De’Zhaun Stribling was five for 77 through the air, while Lacy rushed for 103 yards on 11 carries.

Follow Fox News Digital’s sports coverage on X and subscribe to the Fox News Sports Huddle newsletter.

-

Detroit, MI6 days ago

Detroit, MI6 days ago2 hospitalized after shooting on Lodge Freeway in Detroit

-

Technology3 days ago

Technology3 days agoPower bank feature creep is out of control

-

Dallas, TX4 days ago

Dallas, TX4 days agoDefensive coordinator candidates who could improve Cowboys’ brutal secondary in 2026

-

Health5 days ago

Health5 days agoViral New Year reset routine is helping people adopt healthier habits

-

Iowa3 days ago

Iowa3 days agoPat McAfee praises Audi Crooks, plays hype song for Iowa State star

-

Nebraska3 days ago

Nebraska3 days agoOregon State LB transfer Dexter Foster commits to Nebraska

-

Nebraska3 days ago

Nebraska3 days agoNebraska-based pizza chain Godfather’s Pizza is set to open a new location in Queen Creek

-

Oklahoma1 day ago

Oklahoma1 day agoNeighbors sift debris, help each other after suspected Purcell tornado