Mississippi

In a new documentary, a Pulitzer-winning Atlanta journalist examines the integration of his own Mississippi public school

Photograph courtesy of the Leland School District

Atlanta journalist and Douglas A. Blackmon has a distinguished career working at the Wall Street Journal and the Atlanta Journal-Constitution. In 2009, he won a Pulitzer Prize for his book Slavery by Another Name: The Re-Enslavement of Black Americans from the Civil War to World War II. Now, the Georgia State University professor is tackling a story very close to home as writer and producer of a new documentary, The Harvest.

Debuting September 12 on PBS’s American Experience, The Harvest explores the story of first integrated public school class in Leland, Mississippi, of which Blackmon was a part of. The film is produced by prolific Oscar-nominated filmmaker and producer Sam Pollard (Citizen Ashe, Black Art: In the Absence of Light), who also worked on the documentary adaptation of Slavery by Another Name.

Courtesy of The Harvest

While 1954 Supreme Court decision in Brown v. the Board of Education mandated the integration of the country’s public schools, it did little to change things in Blackmon’s corner of the South, where schools remained defiantly segregated, as did almost every facet of public life in Mississippi. That status quo changed with the 1969 decision in Alexander v. Holmes County Board of Education, which ordered still segregated schools to immediately desegregate. In the fall of 1970, Blackmon’s first grade class was the first in the town’s history to have both Black and white students. For a time, it looked like a civil rights success.

But The Harvest shows the many ways that new forms of segregation were created in the wake of the 1969 decision. Private, whites-only schools popped up. Classes in the newly integrated public schools began to be divided into “smart” and “average” students along largely racial lines. And deep social divisions remained, so that students who spent their days together in classrooms never socialized or visited each others’ homes outside of school. Black-and-white images from Leland yearbooks in the film show Black faces, but those students tended to stand apart, visually testifying to lingering divides.

The dreamy Kodachrome home movie footage that opens The Harvest documents football games, beauty queens, parades, boy scouts, immaculately tended front lawns, and smiling tow-headed children that paint a picture of all-American prosperity. This was hardly the case for Leland’s Black residents, working in virtual indentured servitude and trapped in grinding, inescapable poverty. Their exploitation was so intense many refused to work for white employers and started an encampment, Strike City, outside Leland. Schoolboy Blackmon foreshadowed his future as a journalist when he presented an essay on Strike City to the Leland Lion’s Club. The reaction of the Lions Club members to his sympathetic portrait of Strike City ranged from strained silence to rage.

Photograph by Scherman Rowland/UMASS AMHERST

It was a formative moment for Blackmon. “That moment amplified an interest that I obviously already had in both the civil rights story, but also just a genuine reflection about why were the lives of my Black classmates so radically different than mine?”

The Harvest was initially a storytelling challenge for Blackmon. Like most journalists, Blackmon’s job trained him to be an impartial observer. The idea of talking about his own experiences, narrating the film, even having his own mother, father, and brother interviewed felt a little uncomfortable.

“Sam [Pollard, the film’s producer] thought it was crazy of to even suggest anything else,” Blackmon says. “Sam comes from a very empathetic, human, emotional storytelling kind of approach. And so I think for him, it sounded kind of crazy to suggest that it would not be a very personal story, or that I would not narrate the story. He was right.”

Among the many insights and surprises in The Harvest is how it illustrates, in the voices of Blackmon’s Leland classmates and town residents, just what white privilege looks like—a kind of blindered, willful ignorance that allows great injustice to unfold conveniently outside its peripheral vision. The members of Leland’s white middle class interviewed for the film seemed to lack any inkling of what the foundation of their comfort and contentment is built upon, says Blackmon: “The film is very much about this world that was created by this tradition of extraordinary white privilege.”

Blackmon reached out to people he hadn’t communicated with, in some cases, for 30 years and persuaded them to sit down and recollect with cameras rolling. He says getting people to reveal an unflattering collusion in an oppressive system or the humiliating treatment some Black residents endured was mostly a matter of getting people comfortable. (Pollard often stepped in to interview Black subjects.)

“[The goal was] just to keep people talking and encourage them to go to places that they might have conditioned themselves to avoid because they were uncomfortable,” Blackmon says. At one point in the film, a former Black classmate, Jesse King, recalls the humiliation and shock the day he watched his father’s foreman kick him in front of his wife and children.

Photograph courtesy of The Harvest

The Harvest’s origin was a 1992 essay, “The Resegregation of a Southern School,” that Blackmon wrote in Harper’s about the 10th anniversary of his high school class’s graduation. He was encouraged to write a book about his personal experience of school integration, but the memoir he began to write, he later discovered, did not feel like an accurate recollection.

“I went back to the manuscript and I was startled that some of my memories in the manuscripts, and in my mind, didn’t match up anymore. Either I had gotten clarity, or I had gotten fuzzy about certain things—not so much about whether specific events occurred or didn’t occur, but how I interpreted them or the significance of them. And I realized that that manuscript was not the first draft of a book—it was an artifact,” says Blackmon. “I was, in effect, an unreliable narrator.”

It made more sense, after working with Pollard on Slavery by Another Name, to tell Leland’s story as a film. “I need to be a reporter,” Blackmon realized. “And I need to go back and find other people who were a part of all of these different things, and see how they remember it.”

The history Blackmon documents in The Harvest—how despite the inroads of school integration, public education became a racially divided enterprise over time—continues today. Public schools remain a battleground, Blackmon points out, in states like Florida, where new legislation prevents instructors from teaching students that a person’s race could contribute to their privilege or oppression. He says that under this law, The Harvest would likely be barred from high school classrooms.

Even in Atlanta, a city defined by the Civil Rights Movement, an assault on public education has impacted classrooms.

“We trick ourselves a bit in Atlanta into believing that some of these dynamics were not at play here, when in fact, they really were,” Blackmon says. “Once desegregation of the schools was underway, white people abandoned public school in massive numbers. And that’s what happened in Atlanta. And that’s still the case in Atlanta.”

“There is an increasing movement away from the idea that public schools are the great leveling influence in our society and the place where the rich and the poor become one,” he adds.

A series of screenings and discussions around The Harvest are scheduled through Georgia Humanities. You can view their calendar here.

Advertisement

Mississippi

Southeast Mississippi Christmas Parades 2024 | WKRG.com

MISSISSIPPI (WKRG) — It’s beginning to look a lot like Christmas on the Gulf Coast and that means Santa Claus will be heading to town for multiple parades around the area.

WKRG has compiled a list of Christmas parades coming to Southeast Mississippi.

Christmas on the Water — Biloxi

- Dec. 7

- 6 p.m.

- Begins at Biloxi Lighthouse and will go past the Golden Nugget

Lucedale Christmas Parade

Mississippi

‘A Magical Mississippi Christmas’ lights up the Mississippi Aquarium

GULFPORT, Miss. (WLOX) – The Mississippi Aquarium in Gulfport is spreading holiday cheer with a new event, ‘’A Magical Mississippi Christmas.’

The aquarium held a preview Tuesday night.

‘A Magical Mississippi Christmas’ includes a special dolphin presentation, diving elves, and photos with Santa.

The event also includes “A Penguin’s Christmas Wish,” which is a projection map show that follows a penguin through Christmas adventures across Mississippi.

“It’s a really fun event and it’s the first time we really opened up the aquarium at night for the general public, so it’s a chance to come in and see what it’s like in the evening because it’s really spectacular and really beautiful,” said Kurt Allen, Mississippi Aquarium President and CEO.

‘A Magical Mississippi Christmas’ runs from November 29 to December 31.

It will not be open on December 11th, December 24th, and December 25th.

Tickets can be purchased online or at the gate.

The event is made possible by the city of Gulfport and Coca-Cola Bottling Company.

See a spelling or grammar error in this story? Report it to our team HERE.

Copyright 2024 WLOX. All rights reserved.

Mississippi

Mississippi asks for execution date of man convicted in 1993 killing, lawyers plan to appeal case to SCOTUS

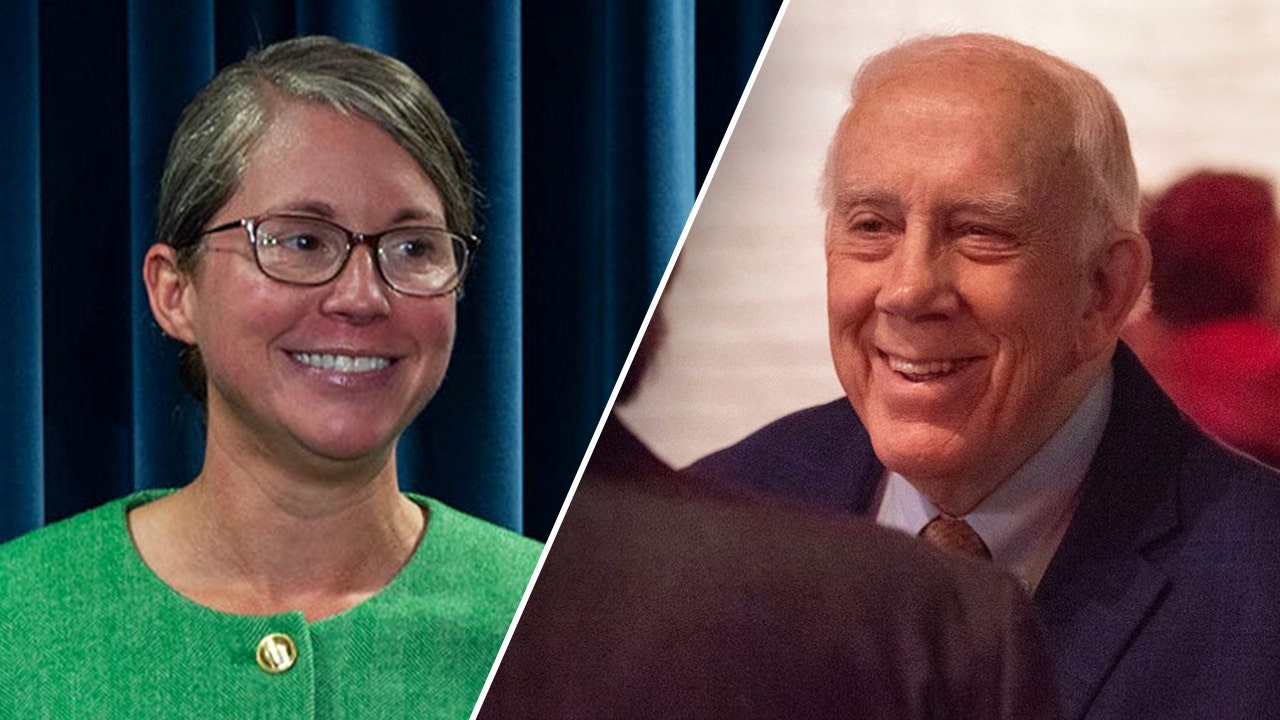

Mississippi Attorney General Lynn Fitch, a Republican, is seeking an execution date for a convicted killer who has been on death row for 30 years, but his lawyer argues that the request is premature since the man plans to appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court.

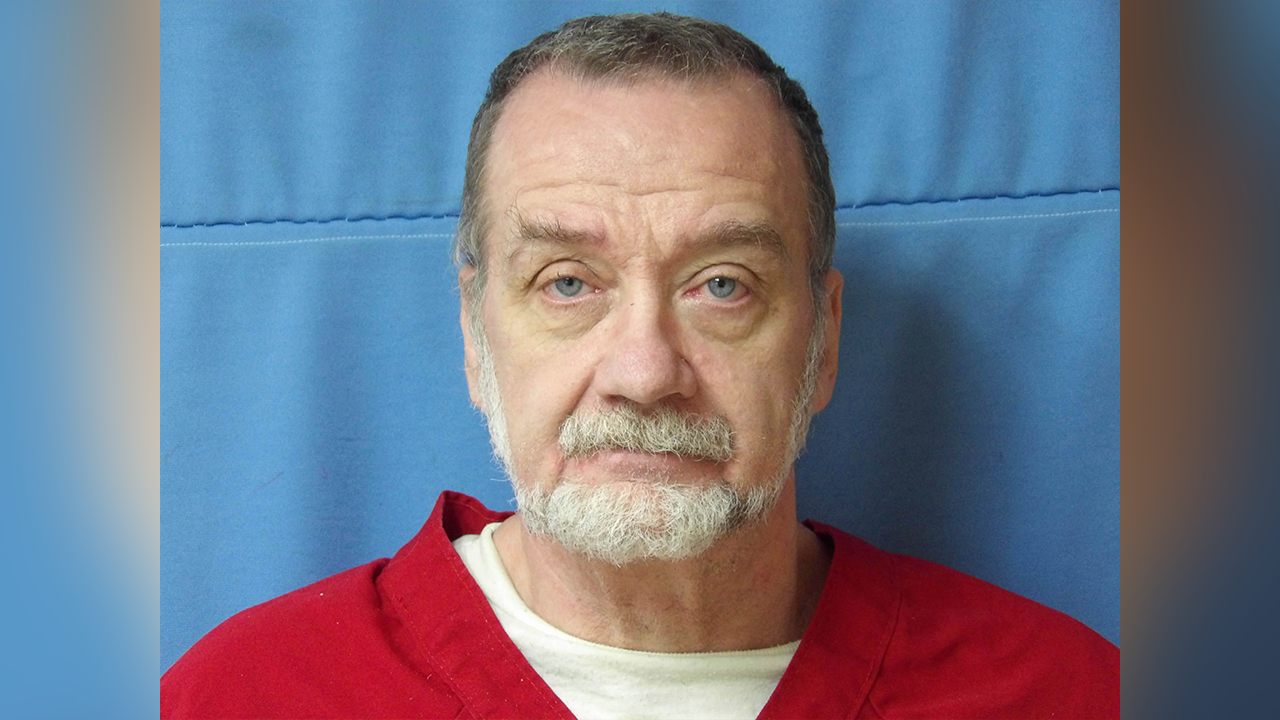

Charles Ray Crawford, 58, was sentenced to death in connection with the 1993 kidnapping and killing of 20-year-old community college student Kristy Ray, according to The Associated Press.

During his 1994 trial, jurors pointed to a past rape conviction as an aggravating circumstance when they issued Crawford’s sentence, but his attorneys said Monday that they are appealing that conviction to the Supreme Court after a lower court ruled against them last week.

Crawford was arrested the day after Ray was kidnapped from her parents’ home and stabbed to death in Tippah County. Crawford told officers he had blacked out and did not remember killing her.

TEXAS LAWMAKER PROPOSES BILL TO ABOLISH DEATH PENALTY IN LONE STAR STATE: ‘I THINK SENTIMENT IS CHANGING’

Mississippi death row inmate Charles Ray Crawford, who was convicted and sentenced to death in 1994 in the 1993 kidnapping and killing of a community college student, 20-year-old Kristy Ray. (Mississippi Department of Corrections via AP)

He was arrested just days before his scheduled trial on a charge of assaulting another woman by hitting her over the head with a hammer.

The trial for the assault charge was delayed several months before he was convicted. In a separate trial, Crawford was found guilty in the rape of a 17-year-old girl who was friends with the victim of the hammer attack. The victims were at the same place during the attacks.

Crawford said he also blacked out during those incidents and did not remember committing the hammer assault or the rape.

During the sentencing portion of Crawford’s capital murder trial in Ray’s death, jurors found the rape conviction to be an “aggravating circumstance” and gave him the death sentence, according to court records.

PRO-TRUMP PRISON WARDEN ASKS BIDEN TO COMMUTE ALL DEATH SENTENCES BEFORE LEAVING

During the sentencing portion of Crawford’s capital murder trial, jurors found his prior rape conviction to be an “aggravating circumstance” and gave him the death sentence. (iStock)

In his latest federal appeal of the rape case, Crawford claimed his previous lawyers provided unconstitutionally ineffective assistance for an insanity defense. He received a mental evaluation at the state hospital, but the trial judge repeatedly refused to allow a psychiatrist or other mental health professional outside the state’s expert to help in Crawford’s defense, court records show.

On Friday, a majority of the 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals rejected Crawford’s appeal.

But the dissenting judges wrote that he received an “inadequately prepared and presented insanity defense” and that “it took years for a qualified physician to conduct a full evaluation of Crawford.” The dissenting judges quoted Dr. Siddhartha Nadkarni, a neurologist who examined Crawford.

“Charles was laboring under such a defect of reason from his seizure disorder that he did not understand the nature and quality of his acts at the time of the crime,” Nadkarni wrote. “He is a severely brain-injured man (corroborated both by history and his neurological examination) who was essentially not present in any useful sense due to epileptic fits at the time of the crime.”

Photo shows the gurney of an execution chamber. (AP Photo/Sue Ogrocki, File)

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

Crawford’s case has already been appealed multiple times using various arguments, which is common in death penalty cases.

Hours after the federal appeals court denied Crawford’s latest appeal, Fitch filed documents urging the state Supreme Court to set a date for Crawford’s execution by lethal injection, claiming that “he has exhausted all state and federal remedies.”

However, the attorneys representing Crawford in the Mississippi Office of Post-Conviction Counsel filed documents on Monday stating that they plan to ask the U.S. Supreme Court to overturn the appeals court’s ruling.

The Associated Press contributed to this report.

-

Science1 week ago

Science1 week agoTrump nominates Dr. Oz to head Medicare and Medicaid and help take on 'illness industrial complex'

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoTrump taps FCC member Brendan Carr to lead agency: 'Warrior for Free Speech'

-

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25739950/247386_Elon_Musk_Open_AI_CVirginia.jpg)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25739950/247386_Elon_Musk_Open_AI_CVirginia.jpg) Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoInside Elon Musk’s messy breakup with OpenAI

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoProtesters in Slovakia rally against Robert Fico’s populist government

-

Health5 days ago

Health5 days agoHoliday gatherings can lead to stress eating: Try these 5 tips to control it

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoThey disagree about a lot, but these singers figure out how to stay in harmony

-

Health2 days ago

Health2 days agoCheekyMD Offers Needle-Free GLP-1s | Woman's World

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoGaetz-gate: Navigating the President-elect's most baffling Cabinet pick