Maryland

Advocates, Lawmakers Hope 2025 Will Be the Year Maryland Stops Subsidizing Trash Incineration – Inside Climate News

For more than a decade, Maryland Sen. Karen Lewis Young tried to get the state to pull the plug on public subsidies for trash incineration, a form of energy that’s considered dirtier than coal. None of the bills have crossed the finish line.

Then came a phone call as she was pulling into her driveway a few weeks ago. On the other end of the line was Bill Ferguson, the Senate president. “He said, ‘This is the year I’m not only going to support the bill, I want to sponsor that bill,’” recalled the Democrat from Frederick County.

On Oct. 18, Ferguson announced he will sponsor legislation in the upcoming General Assembly session to remove waste incineration from the Renewable Portfolio Standard (RPS), the state’s incentives program for renewable energy projects.

“I’ve become increasingly concerned about emissions from the BRESCO incinerator as a public health and environmental justice issue for surrounding neighborhoods,” Ferguson said of the WIN Waste incinerator (formerly known as Wheelabrator and BRESCO), the largest stationary source of industrial air pollution in Baltimore.

Explore the latest news about what’s at stake for the climate during this election season.

Located off I-95, next to the city’s most disadvantaged communities, the incinerator emits hazardous pollutants including mercury, lead, carbon monoxide, nitrogen oxides and fine particulate matter. Those noxious emissions contribute to respiratory issues, heart conditions and other serious health problems, particularly in adjoining neighborhoods.

“As we take steps to incentivize true, clean energy in Maryland, 2025 must be the year that we remove waste incineration from our Renewable Portfolio Standard,” Ferguson declared.

Under Maryland law, electricity providers can buy renewable energy credits (RECs) sold by energy providers—including trash incinerators—and pass the costs of those credits on to consumers in their energy bills. RECs are issued when one megawatt-hour of electricity is generated and delivered to the grid from a renewable energy source.

Lewis Young said she was happy to see Ferguson go from being on the fence a year ago to fully supporting the efforts to deny millions in public dollars to incineration companies.

She’d opposed trash incineration before she entered the Maryland General Assembly in 2015. “For me, the No. 1 issue was the negative environmental effects of burning trash,” she said. “We were spending, on average, $17 million a year to incentivize dirty energy. That money could be better spent elsewhere, not only financial resources but job growth in clean energy industries.”

She said her research led her to believe that more than 80 percent of dirty energy sources like incinerators were located in communities where 25 percent or more of the population identified as either minority or lived below the federal poverty line. “Because of those reasons, I got increasingly enthusiastic and determined to get trash incineration removed as clean energy,” she said.

In the 2024 legislative session, Lewis Young sponsored the Reclaim Renewable Energy Act, which proposed excluding energy derived from burning waste from the RPS. The bill failed to advance out of committee in either chamber.

It was the seventh consecutive year a bill seeking an end to a public subsidy for trash incineration failed to pass. In 2023, a similar bill proposing the removal of trash incineration, factory farm gas and woody biomass from the RPS met the same fate. Because the 2024 bill focused solely on ending credits for trash incineration, advocates were hopeful about its passage. But Maryland Gov. Wes Moore, a Democrat, refused to get behind the bill, attracting the ire of environmentalists.

It’s anyone’s guess if the Moore administration will act differently in the 2025 legislative session. Carter Elliott, a press secretary for the governor, provided a written comment that did not answer the question: “The governor looks forward to working with the state legislature, local leaders, and advocates on behalf of all Marylanders this upcoming session. The Moore administration is working with all partners involved to ensure that we are continuing to put forward legislation that will make Maryland safer.”

Incinerators have been eligible for public subsidies through the state’s clean energy credit system since then-Gov. Martin O’Malley signed legislation in 2011 declaring the electricity generated from burning trash a “tier one” renewable energy, on par with wind and solar.

Also called “waste-to-energy” facilities, trash incinerators like those operated by WIN Waste convert non-hazardous, non-recyclable materials into usable energy through combustion. They also release hundreds of thousands of tons of climate-warming carbon dioxide every year in addition to PM2.5—extremely small particles that get into blood and lungs.

With Ferguson’s support, Lewis Young is hopeful the General Assembly will finally remove trash incineration as “tier one” renewable energy.

Del. Lorig Charkoudian, a Democrat from Montgomery County, said she was thrilled to hear of the Senate president’s commitment. “It’s a very good sign, and I look forward to working with all of my colleagues to make it a reality. Nothing’s a done deal until the entire General Assembly votes to make it happen. And while I join in the optimism, we’re going to continue to work to make sure that it happens.”

Charkoudian stressed that the 2024 legislation was about ending the public subsidy for incineration and is unrelated to the question about waste management. Incineration companies wrongly asserted at the time that removal of the subsidy will lead to waste management problems, she said.

She said that incineration does not belong in the RPS and public dollars should be used to increase the amount of real clean energy on the grid: solar, onshore and offshore wind and hydro.

She said that taking away this subsidy will not make a difference in whether these plants continue to operate. “If you look at their profits and revenue statements, there’s zero evidence to suggest that taking this subsidy away would result in the closure of the plants.”

Charkoudian is also working on a separate “Clean Resource Adequacy Bill” to be introduced in the upcoming session that aims to restructure the RPS, bringing in as much new clean energy generation to the grid as possible while rapidly adding energy storage.

Mary Urban, communications director for WIN Waste Innovations, said the company has recently invested nearly $50 million to upgrade the facility. “Similar legislation has been introduced over the past several years, but each proposal undermined the Renewable Portfolio Standard program’s goal to reduce our reliance on fossil fuels,” she said in emailed comments.

Urban added that Maryland generates minimal energy from wind and solar and relies predominantly on energy from nuclear, natural gas and coal. “Excluding waste-to-energy (WTE) from the RPS requires Marylanders to subsidize out-of-state businesses while ignoring the work WIN does to divert waste from landfills and reduce greenhouse gases while avoiding fossil fuels,” she added.

Between 2012 and 2030, Maryland is set to pay more than $300 million to trash incinerators, according to a March analysis by the nonprofits Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility, Clean Water Action and Progressive Maryland. It showed that the participating trash incinerators emitted more CO2 per megawatt-hour than any other energy sources included in the RPS. Among the facilities operating in Maryland, the WIN Waste incinerator in Baltimore City emitted the highest amount of CO2, estimated at 690,033 tons per year.

In 2022, the most money went to Covanta, which owns and operates a trash incinerator in Lorton, Virginia, and pocketed $11.7 million, the data showed. WIN Waste Innovations, which owns and operates the incinerator in Baltimore, received about $4.2 million through the sale of RECs.

In the past 10 years, the report said, the price of RECs sold by trash incinerators increased more than sevenfold. They are now more expensive than RECs affiliated with wind, a clean, renewable energy source.

Ferguson’s announcement has energized community groups and environmental organizations who have long voiced their opposition to burning trash for energy at public expense.

Jennifer Kunze, Maryland director for Clean Water Action, called Ferguson’s statement a “game changer” and the result of his constituents making sure this issue remains a priority. She said the communities impacted by trash incineration have been “really loud and consistent for years” in highlighting it as a major climate and environmental justice problem that needs to be addressed.

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate Now

She said that there’s still a lot of work that needs to happen between now and the end of the legislative session in April, particularly for making sure that the bill moves forward in both House and Senate committees. “We are really looking for the House now to make it known early that this bill is going to be an environmental justice priority,” Kunze said, adding that a lot depends on House Speaker Adrienne Jones and C. T. Wilson, chair of the House Economic Matters Committee.

“We’re really looking to Gov. Moore, the Maryland Department of the Environment and the Maryland Energy Administration to issue a similar public statement that trash incineration needs to come out of the RPS and won’t be part of the state’s clean energy plan,” Kunze said.

Separately, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency is investigating a federal civil rights complaint alleging that Baltimore City’s 10-year solid waste plan failed to commit necessary resources to end the city’s reliance on the WIN Waste incinerator.

The South Baltimore Community Land Trust, the community group that filed the complaint along with the Chesapeake Bay Foundation and the Environmental Integrity Project, called Ferguson’s announcement “a critical step forward for environmental justice.” In a statement, the group said: “South Baltimore residents have long suffered the health and development impacts of the BRESCO incinerator—the largest single source of air pollution in Baltimore and the source of toxic ash filling the city’s landfill also located in the neighborhood.”

Kim Coble, executive director of the Maryland League of Conservation Voters, said the lack of progress on trash incineration during the last legislative session was listed in her group’s 2024 environmental scorecard as an impediment to the state’s transition to clean energy.

Coble said the inability to remove polluting energy sources from the RPS was one of the many bills with environmental justice implications that the 2024 General Assembly session failed to make progress on.

“Unfortunately, none of the bills passed that were directly related to environmental justice. So that’s a problem. The same with climate and energy,” she said. “And none of the three bills related to generating revenue [for climate action] got out of the committee.”

Lewis Young said issues of energy and climate action will take center stage during the upcoming General Assembly session. She expects bills calling for making polluters pay—that type of proposal “met some pushback” from the administration last year, she said, alluding to the Responding to Emergency Needs from Extreme Weather (RENEW) Act. The bill, which failed to pass, aimed to make oil and gas companies pay for their pollution.

Other bills calling for new penalties and incentives will also likely drop next year to generate momentum for meeting the state’s climate and emissions reduction goals, she said.

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,

Maryland

November 21 Colder Winds Bring Snow To Central Maryland And Winter Storm Warning In The Mountains – Just In Weather

November 21, 2024

Thursday Morning Report

The squall line last night validated and even overachieved expectations. Winds gusted over 50 mph in many areas AND much needed rainfall added up to 0.94” in Baltimore through midnight. More was added afterward.

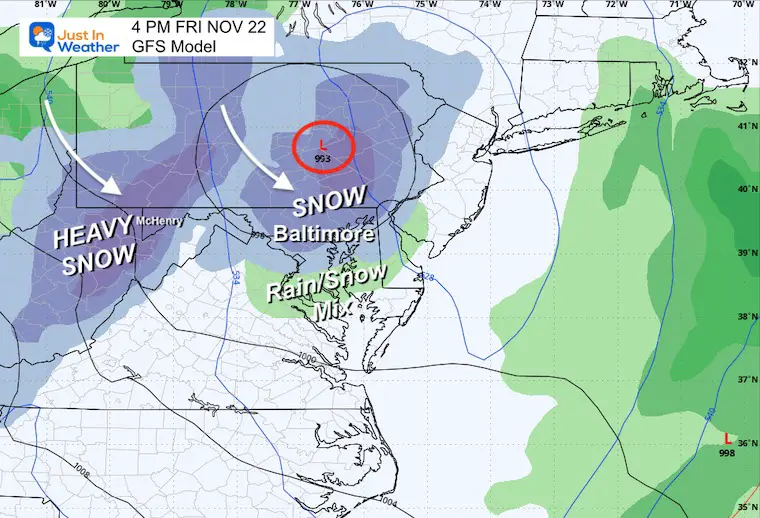

Colder air and a large upper-level trough will settle in Pennsylvania on Friday. This will bring in a taste of winter. The expectations for snow have now expanded to Central Maryland, and yes, it might be cold enough for some stickage on grassy areas.

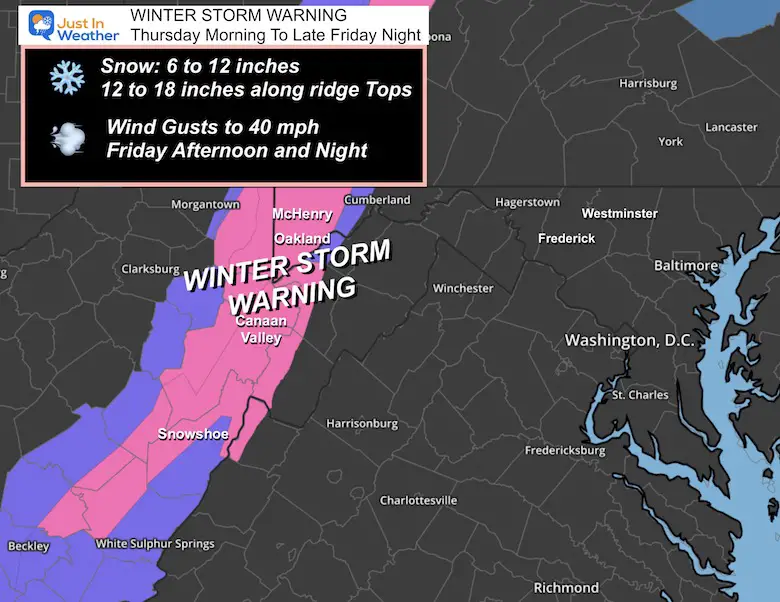

A Winter Storm Warning is in place for the high mountains of far Western Maryland and West Virginia. Snow is still expected to reach 1-foot accumulation along with 50 mph winds.

Let’s take a look……

Morning Surface Weather

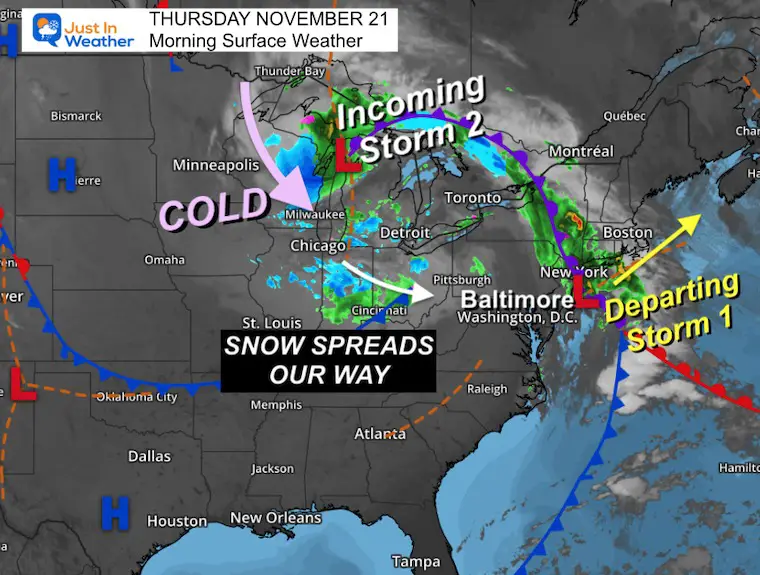

Storm 1, which brought us rain and wind, is moving away and sending much-needed rain to the drought areas of Metro New York and New England.

Storm 2 is the main event that will pivot from the Great Lakes and nearly stall in Pennsylvania on Friday. This will include a strong upper-level source of cold air and instability. Snow will spread our way and enhance over the Appalachian mountains.

Weather Preview

Storm Animation Today through Saturday Night

Watch the main storm spin in PA and pivot the next wave of energy that will enhance the snow on Friday, then pull away this weekend.

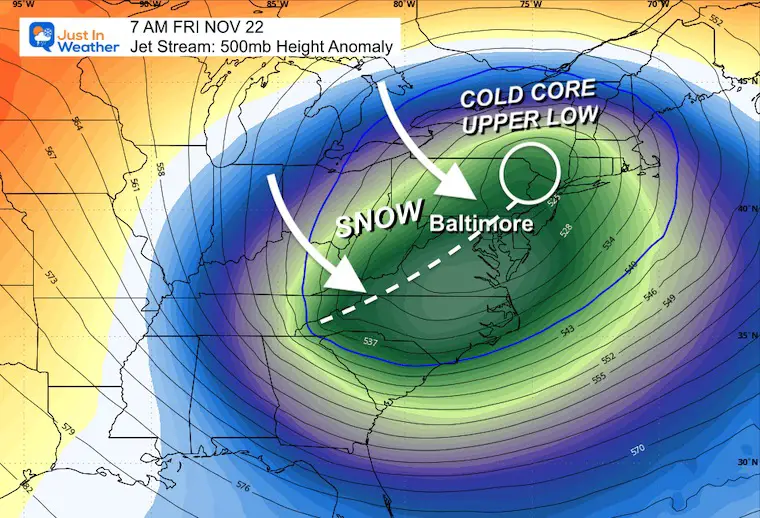

Jet Stream Friday Morning

The core of the cold air will be over our region. There is a trough swinging through the Southeast US with enough enhanced energy to develop snow.

Snow and Rain Mix Friday

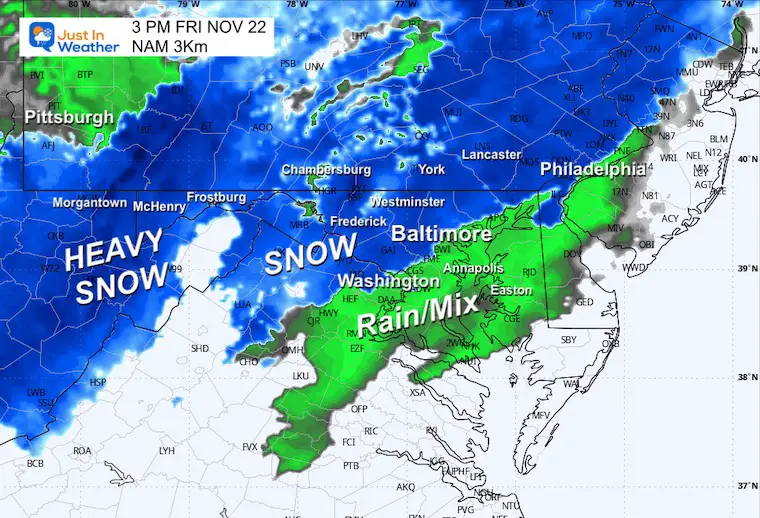

Notice the blue shading (snow) into metro Baltimore. A closer look is below.

TODAY

Wind Forecast 7 AM to 7 PM

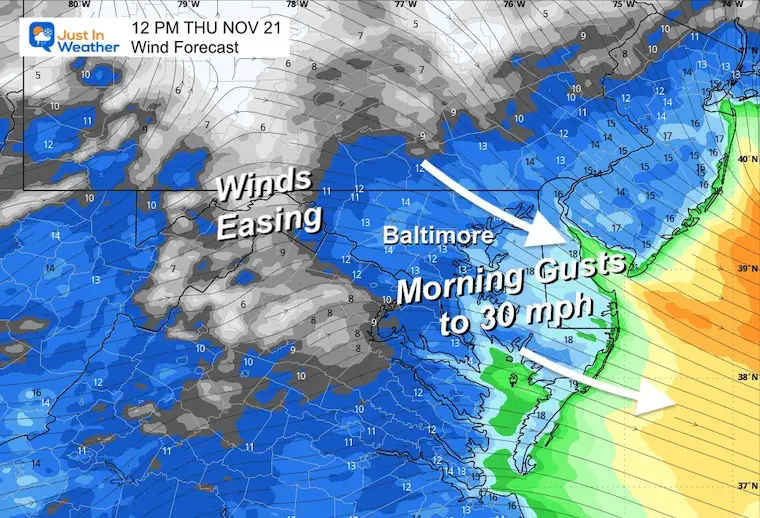

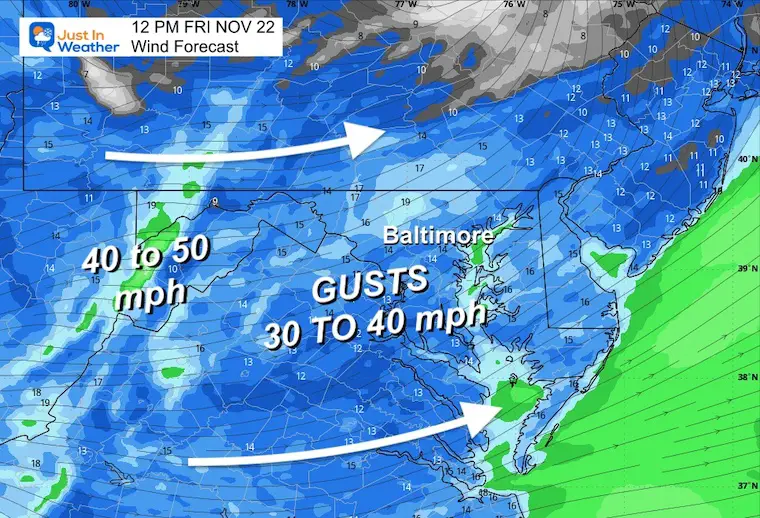

Wind Gusts at Noon

The stronger winds will be moving east, so it will be less windy this afternoon.

Radar Simulation: Noon to Midnight

There will be some showers with rain and maybe flakes after dark.

Heavy snow will get going in the mountains.

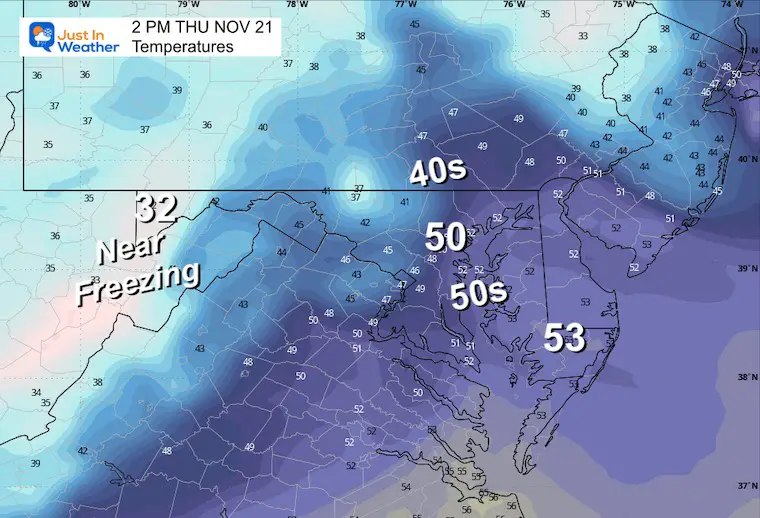

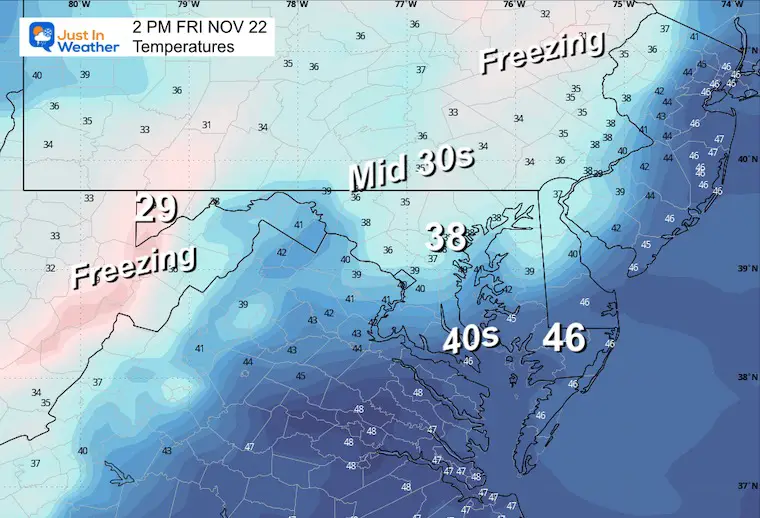

Afternoon Temperatures

Radar Simulation Tonight

7 PM Wed to 7 AM Thu

CLIMATE DATA: Baltimore

TODAY November 21

Sunrise at 6:57 AM

Sunset at 4:48 PM

Normal Low in Baltimore: 35ºF

Record 16ºF in 1951

Normal High in Baltimore: 55ºF

Record 79ºF 1900

Baltimore Drought Update

- 0.94” of rain fell Thursday… The updated deficit:

- 6.66 inches BELOW AVERAGE rainfall since September 1st

- 7.12 inches BELOW AVERAGE rainfall since January 1st

- THE BURN BAN REMAINS IN PLACE

FRIDAY NOVEMBER 22

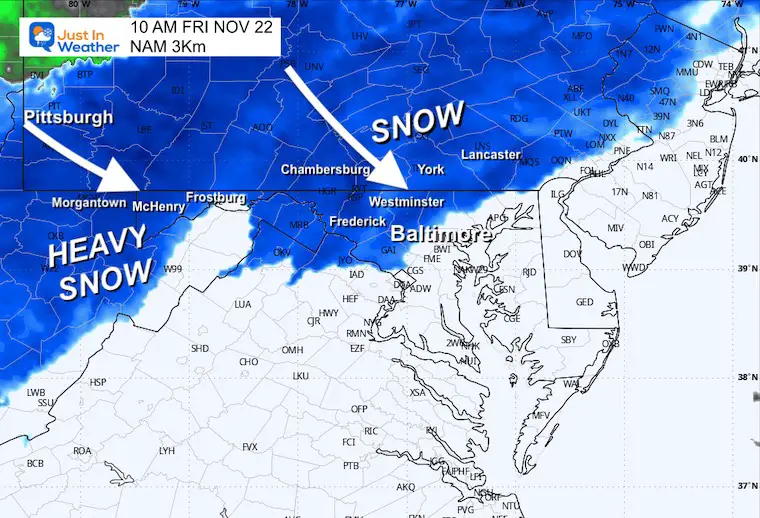

Turning colder with developing snow from the North, and it will reach the northern suburbs during the morning.

Snow will mix with rain near and south of Baltimore.

Heavy snow will be raging in the mountains.

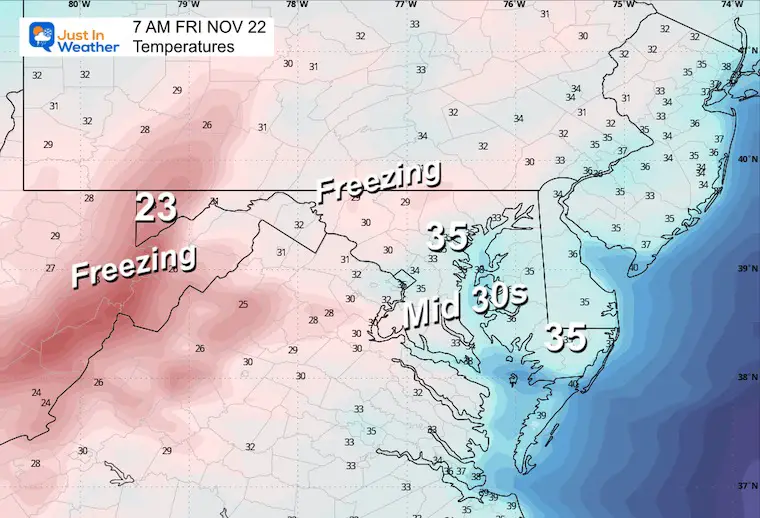

Morning Temperatures

Morning Radar Simulation

Radar Forecast 7 AM to Midnight

Winds At Noon

Afternoon Radar

Afternoon Temperatures

WINTER STORM WARNING

This includes Garrett County, MD, and the high mountains of PA and WV.

Snow 6 to 12+ inches with wind gusts to 50 mph.

Note this is over the extreme drought region and is much needed.

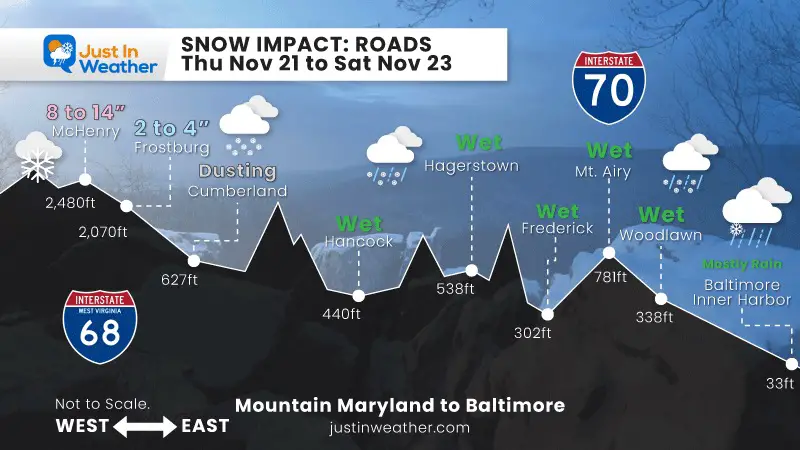

Snow Roads Profile

Snow Forecast Models

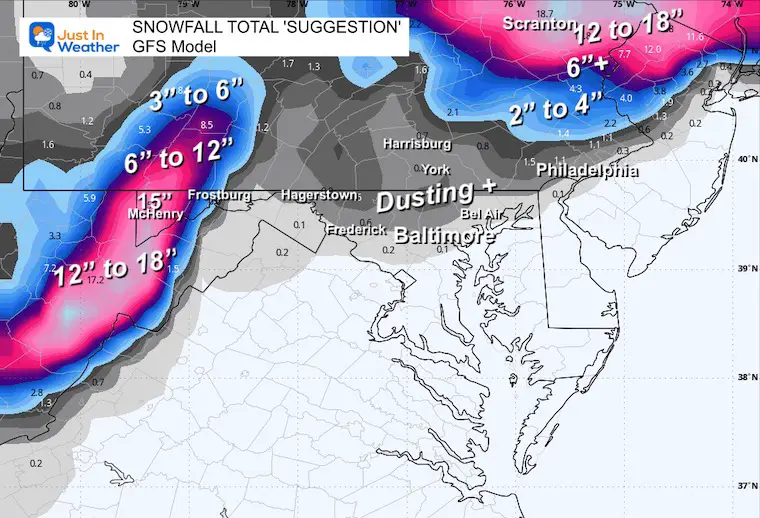

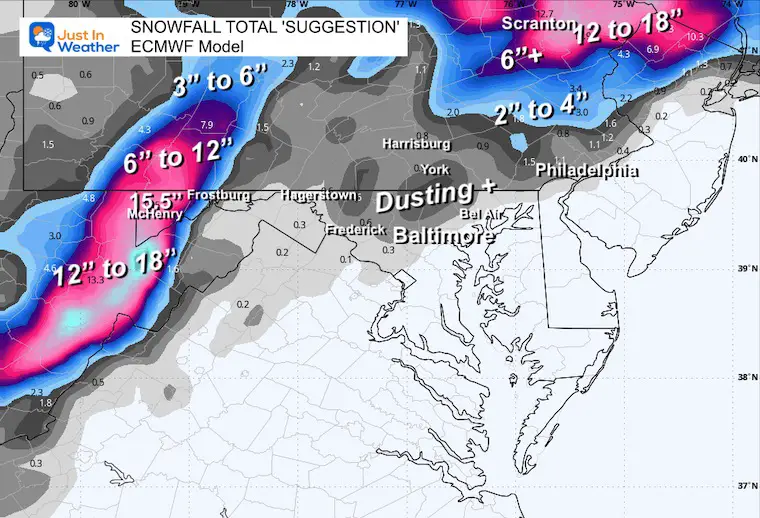

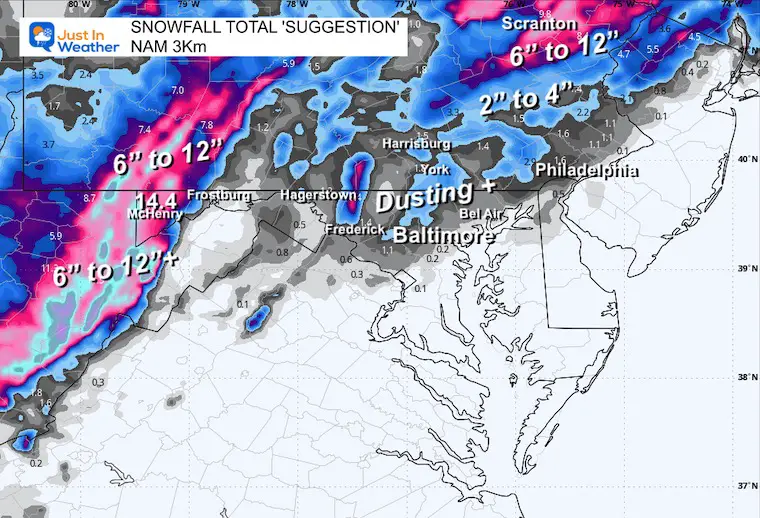

There is a lot of agreement between the GFS and ECMWF.

Yes, I see a dusting or more on the grassy areas north of Baltimore.

GFS

ECMWF

NAM 3Km

In Case You Missed It

My Winter Outlook Report

7 Day Forecast

- Colder air will continue to spill in through Saturday.

- Some rain showers later today with a mix of flakes.

- Heavy snow develops in the mountains.

- Snow and mixed showers will expand into Central Maryland on Friday.

- Briefly mild early next week. Then, rain on Wednesday may set up a colder Thanksgiving storm.

Subscribe for eMail Alerts

Weather posts straight to your inbox

Sign up and be the first to know!

Please share your thoughts and best weather pics/videos, or just keep in touch via social media.

SCHEDULE A WEATHER BASED STEM ASSEMBLY

Severe Weather: Storm Smart October and next spring

Winter Weather FITF (Faith in the Flakes): November To March

Click to see more and send a request for your school.

THANK YOU:

Baltimore Magazine Readers Choice Best Of Baltimore

Maryland Trek 11 Day 7 Completed Sat August 10

We raised OVER $104,000 for Just In Power Kids – AND Still Collecting More

The annual event: Hiking and biking 329 miles in 7 days between The Summit of Wisp to Ocean City.

Each day, we honor a kid and their family’s cancer journey.

Fundraising is for Just In Power Kids: Funding Free Holistic Programs. I never have and never will take a penny. It is all for our nonprofit to operate.

Click here or the image to donate:

RESTATING MY MESSAGE ABOUT DYSLEXIA

I am aware there are some spelling and grammar typos and occasional other glitches. I take responsibility for my mistakes and even the computer glitches I may miss. I have made a few public statements over the years, but if you are new here, you may have missed it: I have dyslexia and found out during my second year at Cornell University. It didn’t stop me from getting my meteorology degree and being the first to get the AMS CBM in the Baltimore/Washington region.

One of my professors told me that I had made it that far without knowing and to not let it be a crutch going forward. That was Mark Wysocki, and he was absolutely correct! I do miss my mistakes in my own proofreading. The autocorrect spell check on my computer sometimes does an injustice to make it worse. I also can make mistakes in forecasting. No one is perfect at predicting the future. All of the maps and information are accurate. The ‘wordy’ stuff can get sticky.

There has been no editor who can check my work while writing and to have it ready to send out in a newsworthy timeline. Barbara Werner is a member of the web team that helps me maintain this site. She has taken it upon herself to edit typos when she is available. That could be AFTER you read this. I accept this and perhaps proves what you read is really from me… It’s part of my charm. #FITF

Maryland

Damp and cold end to Maryland’s week

Watch CBS News

Be the first to know

Get browser notifications for breaking news, live events, and exclusive reporting.

Maryland

Ex-teacher who sexually abused 14-year-old Maryland student to serve fraction of 30-year sentence

A former middle school teacher who repeatedly sexually abused a 14-year-old student in Maryland has been sentenced to three decades in prison, but she’ll only serve one year, a judge ruled.

Melissa Marie Curtis, 32, pleaded guilty to three counts of a third-degree sex offense on June 20, according to information from the Montgomery County District Attorney’s Office and District Court of Maryland court papers obtained by USA TODAY on Wednesday.

The Montgomery County Police Department initiated an investigation in early October 2023 when the eighth-grade victim, now an adult, reported he was sexually abused by Curtis who was a teacher at Montgomery Village Middle School, according to a previous news release from the agency.

At the time of the offenses, detectives reported, the student was 14 years old and Curtis was 22.

Judge: Teacher to serve 12 months in jail

Curtis, who is from the town of Upper Marlboro in Prince George’s County, was sentenced to 30 years in prison on Friday, a spokesperson for the Montgomery County District Attorney’s Office told USA TODAY Wednesday.

But Montgomery County Circuit Court Judge Theresa Chernosky suspended most of Curtis’ sentence, allowing her to serve 12 months year in jail followed by five years of supervised probation, the spokesperson said.

When she is released, Curtis must register as a sex offender, the spokesperson said, and will not be permitted to have unsupervised contact with minors other than her children.

The prosecutors office did not respond to a request for comment about the sentencing.

Teacher abused 14-year-old in classroom, car, at home

The victim told detectives the abuse began in 2015, the spokesperson said, when he volunteered for an after-school program that Curtis was running and “they were often alone together”

Charging documents show the victim told detectives Curtis sexually abused him in a classroom, in a car, at his home, and as well as Curtis’ home “more than 20 times” when he was in middle school. The complaint goes onto say Curtis also gave the boy drugs and alcohol multiple times.

A warrant for Curtis’s arrest was obtained on Oct. 31, 2023 and Curtis turned herself in on Nov. 7, 2023, officials reported.

At the time, Curtis had been a teacher for about two years in Montgomery County and taught at Lakelands Park Middle School as well.

A spokesperson told Fox 5 Curtis left Montgomery County Public Schools in 2017.

USA TODAY has reached out to Montgomery County Public Schools.

Natalie Neysa Alund is a senior reporter for USA TODAY. Reach her at nalund@usatoday.com and follow her on X @nataliealund.

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoHerbert Smith Freehills to merge with US-based law firm Kramer Levin

-

Business1 week ago

Column: OpenAI just scored a huge victory in a copyright case … or did it?

-

Health1 week ago

Health1 week agoBird flu leaves teen in critical condition after country's first reported case

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoColumn: Molly White's message for journalists going freelance — be ready for the pitfalls

-

World1 week ago

Sarah Palin, NY Times Have Explored Settlement, as Judge Sets Defamation Retrial

-

Politics4 days ago

Politics4 days agoTrump taps FCC member Brendan Carr to lead agency: 'Warrior for Free Speech'

-

Science2 days ago

Science2 days agoTrump nominates Dr. Oz to head Medicare and Medicaid and help take on 'illness industrial complex'

-

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25739950/247386_Elon_Musk_Open_AI_CVirginia.jpg)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25739950/247386_Elon_Musk_Open_AI_CVirginia.jpg) Technology3 days ago

Technology3 days agoInside Elon Musk’s messy breakup with OpenAI