For the last eight years, New Orleans resident Lewis “Duck” Pieratt has worked on local TV and film sets building and operating the cranes and dollies for cameras.

Pieratt had worked his way up, starting off sweeping floors before moving on to making props and ultimately to his current job as a grip.

The long hours during productions are grueling — he typically clocks in 60-80 hours a week. But with most of that coming as overtime or double-time pay, Pieratt was making good money, averaging anywhere between $8,000-$10,000 in a good month, he says.

Plus, as a member of the local chapter of International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees (IATSE) for the last decade, he was able to get health insurance and a pension. He even fulfilled his longtime goal of buying a house.

It’s “just a lot of stability … we make enough money to where in the lean times you have money saved up,” Pieratt says. But nothing could have prepared him for the past nine or so months.

Now, he says, “There’s barely nothing … I know people who haven’t worked since November.”

Long before the national writers union went on strike in May or the actors union joining them on the picket line July 14, work had started drying up. That’s because the heads of TV and film production companies already knew they likely wouldn’t meet worker demands for protections and benefits when the major union contracts expired in the spring and summer.

So rather than start new productions and have them or the promotion of them halted by strikes, major studios and distributors, like Disney/ABC/Fox, Paramount/CBS, NBCUniversal, Warner Bros. Discovery (HBO), Apple, Netflix and Amazon, began holding off on new projects altogether.

As a result, opportunities in the industry have been drying up since the end of 2022, leaving thousands of people in Louisiana out of work before the strikes officially started.

Trey Burvant, president of The Louisiana Film & Entertainment Association, compared the current state of the industry — with only commercials or indie projects left shooting — to the pandemic shutdowns.

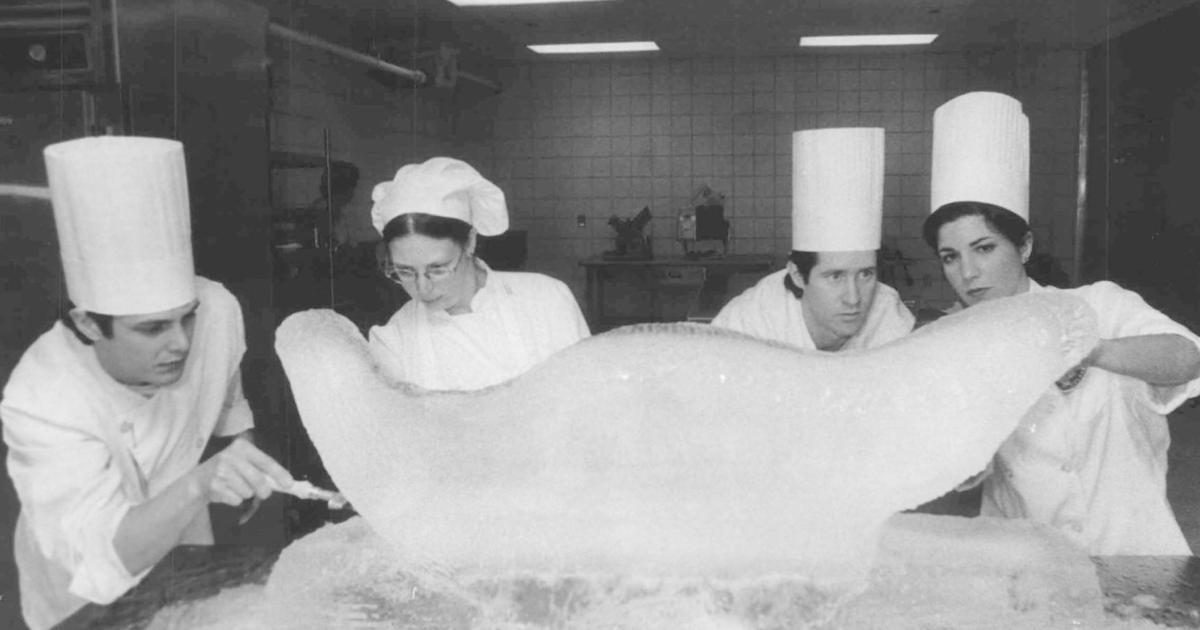

New Orleans grip Lewis “Duck” Pieratt (middle) with Matthew Modine (left) and Allison Janney (right) on the set of “Breaking News in Yuba County.”

“You’ve got empty stages,” he says. “You’ve got folks that have been used to working for years, some of the best in the industry, sitting on the sidelines looking for other work.”

Pieratt says the situation has been “devastating” for him and his friends in the industry. He says he’s run out of unemployment benefits, has had to max out credit cards and is in the process of applying for a mortgage forbearance to temporarily pause or decrease his monthly housing payments.

Like many workers in his position, Pieratt makes clear he doesn’t blame the unions on strike for his current financial situation. Another local grip John Vinson agrees, arguing the studios appear to be using the strikes as part of a broader play against labor.

“We’re all pretty much slowly drowning right now, and I think that’s really the point,” Vinson says. “While our union (IATSE) isn’t striking, we have negotiations coming up next year, and I see this not just as a ‘We’re gonna try and starve out the writers and actors.’ … They’re trying to starve out anybody else who has upcoming negotiations.”

And with no clear end in sight, the forced shutdown continues to create uncertainty for the workers who fill the 10,000 direct and indirect jobs The Louisiana Film & Entertainment Association estimates are created by the industry in the state.

“This is not an elitist problem, it’s not an actor problem and it’s not a Hollywood problem,” says character actor Billy Slaughter. “It’s about glaring, gross inequities between the actual laborers in the industry working long days (in) hard conditions to create the content versus what those (executives) who are profiteering off of that content are making.”

While eyes have been on striking celebrities like Fran Drescher, the president of The Screen Actors Guild – American Federation of Television and Radio Artists (SAG-AFTRA), or the cast of “Oppenheimer” walking out of the film premiere, as in other industries, the majority of workers who make TV shows and movies possible aren’t rich or famous.

That’s true for Louisiana’s film and TV industry and its epicenter in New Orleans, the “Hollywood South” spurred and sustained by generous tax credits.

“The celebrities, the rich and famous make up the top 1% of our industry,” says Slaughter, who has acted in more than 100 TV shows and movies. “The other 99% of our industry are rank-and-file, hard working-class folks … most working paycheck to paycheck, like the average American, just trying to pay their bills and feed their families.”

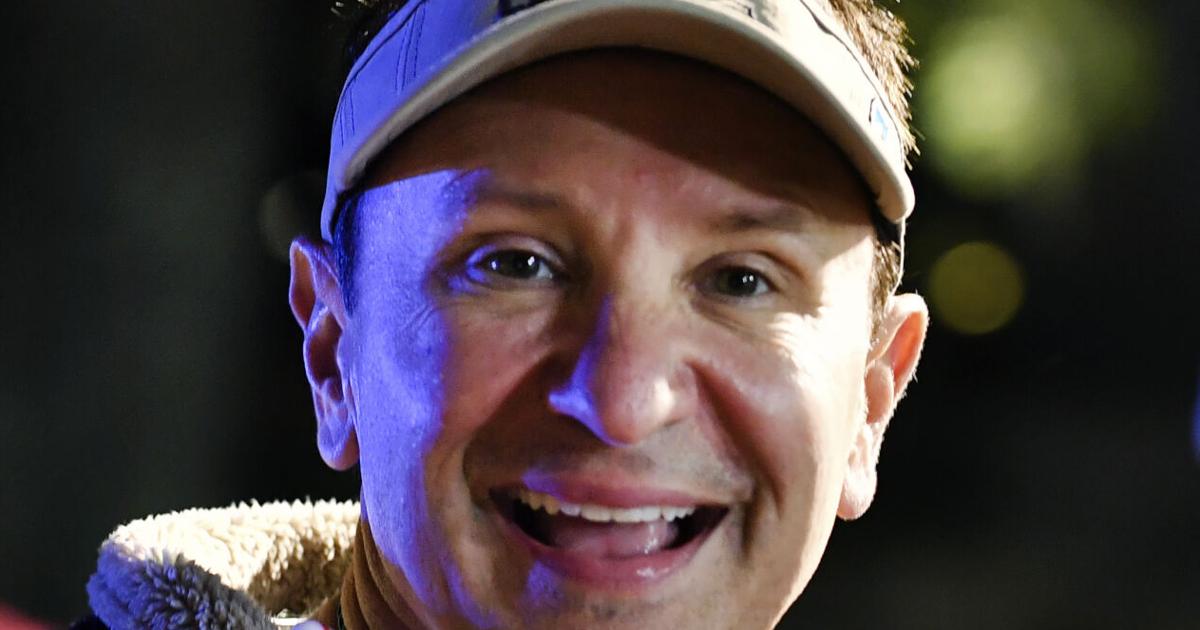

Billy Slaughter at the premiere of “Jack Reacher: Never Go Back” with Tom Cruise in the background.

The industry provides many well-paying blue collar and technical jobs that don’t require a college degree, from camera and equipment operators to set builders and decorators.

“This business gives the opportunity for people of all backgrounds to flourish in something that you get trained on the job for,” Vinson says. “It really does have its merits in being able to help build a sustainable middle class in that region if you let it put itself to work and keep the conditions reasonable, which has always been a problem.”

Those jobs on TV and film sets can last months, even the bulk of a year, but actors and writers are on a different schedule. For more minor roles, actors may need to come to set for a day to film only a few times a year. Screenwriters may sell a screenplay for a seemingly large sum of money, but it could be years before they sell their next project.

Between roles, actors and writers typically rely on residuals, income earned from the replaying of past projects, such as each time a show runs on broadcast or cable TV. But with the shift of the industry from largely based on broadcast TV to being dominated by streaming platforms, they’re typically paid a lump sum to have the content on the platform without any pay bump for a show’s success.

Casting director Ryan Glorioso says it’s a far worse deal for his husband, actor Robert Lucien Larrivière. “Actors [used to be able to] live off their residuals,” he says. “That’s not the case anymore.”

Grip John Vinson on set.

That makes a difference when it comes to eligibility for union benefits, like health insurance. SAG members must make roughly $26,000 a year from acting or act for at least 102 days during the year to qualify for union health insurance. The vast majority of actors simply don’t. Meanwhile, Writers Guild of America members need to make nearly $42,000 to qualify.

Even in good times, when there may be close to 20 different movies being filmed in New Orleans at once, many local actors and writers have second jobs, such as teaching. “Every actor I know in this town, they have to have a second job to live regardless,” says David DuBos, a local writer, director and editor. (David DuBos is the brother of Gambit Political Editor Clancy DuBos.)

Meanwhile, executives of studio and distribution giants are making tens of millions of dollars annually. Last year, Warner Bros. Discovery paid chief David Zaslav more than $39 million, and Netflix co-CEO Ted Sarandos was paid more than $50 million.

“Our love of the industry is extremely exploitable by people who are making millions of dollars,” Vinson says.

New Orleans grip Lewis “Duck” Pieratt (bottom left) and his crew Grip Systems from “Twisted Metal,” which premiered July 27 on Peacock.

The rise of streaming services over the last decade has meant smaller residuals for many, and Artificial Intelligence technology becoming a viable tool in the last handful of years threatens to make some jobs almost obsolete in the near future.

Given the tight margins with which workers in the industry already live, those issues have become the predictable points in negotiations between the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers (AMPTP) and the actors and writers unions, leading them to go on strike together for the first time in 63 years.

“This didn’t catch anyone by surprise,” Slaughter says. “It was not only a long time coming, it was long overdue because our industry is now run by the streaming platforms.”

While the shutdown persists, people working in film and TV have had to look for other work in the meantime. It hasn’t been easy for some, especially for longtime industry workers.

Vinson, who has worked in the industry for more than two decades, says he drove for UberEats for a few months, but the money he was making wasn’t enough to justify the wear and tear on his car. Plus, he says, he’d be a hard sell for a service industry job.

“I go in and say, ‘I haven’t worked in the service industry for 23 years. Would you like to hire me until I’m gonna quit as soon as the industry strikes back up?’” he says.

Glorioso, the casting director, is in a similar boat. “I’ve been doing the same thing for so long I wouldn’t know what other work to pick up,” he says.

New Orleans casting director Ryan Glorioso has been out of work due to the shutdowns.

Even those who have managed to find other work are often taking significant pay cuts.

Set decorator Paul Brion went back to his old line of work managing a produce company, now earning $10 less an hour than he was earning on set. Plus, he can’t pick up extra work on the weekends like he used to do.

“It just messes everything up when you think you have something solid that’s well-paying, and then it just goes away and you have to figure something else out,” Brion says.

Pieratt would typically fall back on construction work, but he says he couldn’t find that either, attributing it to the city’s characteristically slow summer months. He didn’t have restaurant experience but has been grateful to have found work at a local barbecue restaurant for the past two months.

Still, he says, he’s making about $2,000 a month there, a fifth of what he was making in a good month as a grip.

“It’s extremely stressful,” he says. “I have a 9-year-old little girl … that counts on me.”

While finding other work may help pay some of the bills, it’s not a long-term fix for career industry workers who have health insurance and retirement benefits through a union. Only work in the field counts toward the income requirements for their benefits.

“You’re working toward a retirement goal of health and pension, and if you don’t make that in a year, then you don’t get any contributions to your health and pension,” says Glorioso, who is on SAG’s insurance through his husband. “For the person who has made this their career, those things are important.”

New Orleans grip John Vinson has worked in the TV and film industry for more than two decades.

Those who moved to New Orleans to work in the industry may have to leave as the shutdowns continue. Pieratt says he met someone who moved to New Orleans from Dallas to work in costuming when the industry was doing well and is now considering moving back to Dallas where she has family.

Some may ultimately leave the field altogether. Vinson says he worries about how much skilled labor the field will lose from “people who either were just starting and had promise to people who were getting close to retirement to members who already had one foot in the door and one foot out at this point.”

“Because it grates on you,” he adds. “It’s not a very easy industry to occupy for the people that make the movies.”

Stage 4, part of the expansion of Second Line Stages in New Orleans is seen Thursday, Nov. 3, 2022.

The effects of the shutdown extend beyond film and TV industry workers, too. According to The Louisiana Film & Entertainment Association (LFEA), the state’s film lobby, last year the industry spent $900 million in the state and contributed $350 million in wages for Louisiana workers.

Burvant, LFEA president, says each production functions as “its own pop-up business” supporting other businesses in the area. That includes staff and crew taking costumes to dry cleaners on the daily, hiring dog walkers for long days and ordering food and catering from local restaurants.

“When we had between 16 and 18 films filming in the Greater New Orleans area … those staff members that work inside the office, they’re ordering lunch every single day from a different restaurant, every single day for 40 people,” Burvant says. “The scale of it is really large when you think about it.”

Yet, so far, AMPTP hasn’t sat down with the unions since they began striking, and it could be months before they resume negotiations.

A studio executive and insiders told Deadline in July that internally there have been discussions of waiting until late October before going back to the negotiating table with the Writers Guild.

“The endgame is to allow things to drag on until union members start losing their apartments and losing their houses,” the executive said. AMPTP publicly disputes that.

Even when WGA and SAG come to a deal with AMPTP, only some in the industry will be able to pick up work immediately. Depending on where their job falls in the creative process (pre-production, production, post-production), it could be even longer.

The IATSE Local 478 building in Mid-City.

Pieratt estimates that even if producers and the actors and writers unions came to an agreement today, he wouldn’t have work until October. Worst case scenario, he worries he could be out of work until February.

But when the shutdown finally ends, there’s likely to be a boom in work, finishing previous projects and starting new productions.

With the Louisiana Legislature extending film and TV tax credits through 2031, that could mean several busy years for the local industry with potentially better working conditions and protections — though upcoming IATSE negotiations next year could complicate matters further.

“Once it does resolve, then it’s going to be bonkers crazy again, kind of like it was after Covid,” Burvant says.

“We just have to weather the storm first,” Slaughter says. “But we know we do that as good as anyone.”