Science

Why We Love Flaco

As soon as upon a time, there was an owl named Flaco who lived in a small zoo in the midst of an enormous park in America’s largest metropolis. His story was a cliffhanger about escape and freedom and resilience.

As CNN, The Guardian and The Each day Mail joined New York-based media in recounting Flaco’s adventures, concern in regards to the owl who escaped from the Central Park Zoo unfold past his hometown. New Yorkers and vacationers adopted his story with a combination of tension and hope — fearful that after a lifetime in captivity, the owl wouldn’t know easy methods to feed himself or hold himself protected.

Early headlines like “Central Park Zoo Owl Nonetheless on the Free” advised that Flaco’s escape was a variation on the plot of the animated film “Madagascar,” by which a discontented zebra abandons the comforts of the Central Park Zoo and goes on the lam. However the newest chapter within the story of Flaco — who was born in captivity and made “his public debut” on the zoo in 2010 — started with a violent act that endangered his life.

When a vandal minimize the wire mesh on his enclosure on Feb. 2, the one world Flaco knew was forcibly ruptured — a trauma that might have confirmed deadly. From his micro-apartment (furnished solely with some tree branches, pretend rocks and a painted mural of a mountain panorama), Flaco the Eurasian eagle-owl was all of the sudden free in Central Park and uncovered to all of the real-life perils and thrills of Gotham.

It was a type of existential second for the owl: his species is native to a lot of Europe and Asia, however not North America, and there he all of the sudden was, possibly the one one in all his type within the wild on your entire continent. In his first hours and days outdoors the zoo, Flaco “seemed burdened,” mentioned Karla Bloem, government director of the Worldwide Owl Middle. Even his flying was a little bit wobbly at first, she advised; like “somebody who’s been residing of their front room” for years, it took some time “to construct up a little bit muscle and energy.”

By no means earlier than had the owl seen such extensive open areas. By no means earlier than had he been harassed by squirrels, and noisy blue jays and streetwise crows. It was superb to observe Flaco study, mentioned Molly Eustis, a stage supervisor and owl lover, and “assume ‘wow that is in all probability the primary time in his life he’s been that top up in a tree!’ and to assume how that should really feel for him. Or the primary time he caught a rat! Or felt the rain falling throughout him.”

Regardless of the stereotype of owls as scholarly sorts, specialists say they are typically affected person, sensible minded creatures of behavior. Even so, owls all through historical past have exerted a magnetic maintain over our imaginations. Maybe no different creature has been invested with such contradictory meanings throughout so many various cultures — as a protecting spirit, a totem of erudition and an omen of dying.

Centuries earlier than Hedwig grew to become Harry Potter’s loyal sidekick, the owl was often called a companion to Athena, the goddess of knowledge and warfare — probably due to the hen’s phenomenal imaginative and prescient and talent as a hunter. In his twentieth century adaptation of the King Arthur legend, T.H. White gave the long run king’s tutor, the magician Merlyn, a companion named Archimedes — a speaking owl who teaches the younger Arthur easy methods to fly.

Owls are not any much less in style characters in folks tales and youngsters’s books — like Owl in “Winnie-the-Pooh,” who spells his title “Wol” and likes to inform household tales.

Partially, it’s owls’ sense of thriller, their nocturnal nature and elusiveness that account for his or her energy to captivate. Or, as Deborah Jaffe, a birder and lifelong New Yorker, observes: “Owls have at all times been the toughest birds to see, which makes them essentially the most thrilling varieties of birds to see.”

Partially, it’s their expressive eyes and virtually human countenance. Bella Hatkoff, an artist who has volunteered on the Wild Chicken Fund, factors out that owls are virtually good illustrations of what the zoologist Konrad Lorenz known as “child schema” — a idea that the options of a human toddler (spherical head, massive eyes, roundish physique) are likely to set off protecting feelings. Animals like panda bears and kittens additionally match this blueprint for “cuteness,” as do characters like Pikachu and Child Yoda.

A captivating owl was drawn some 30,000 years in the past within the Chauvet Collapse southern France — with its expressive little ear tufts, it bears a outstanding resemblance to Flaco. And there are dozens of drawings, ceramics and sculptures of owls created by Pablo Picasso — all impressed by a little bit owl with an injured talon that he and his companion Françoise Gilot rescued in 1946. Picasso recognized with the owl’s interrogatory gaze, and he later created a self-portrait of himself as an owl — together with his personal piercing eyes staring out from a line drawing of the hen.

Many New Yorkers, particularly these confined to small residences throughout Covid, recognized with Flaco’s story. David Barrett, who runs the favored Twitter account Manhattan Bird Alert — which many individuals have relied upon to trace Flaco’s journey — famous that individuals who arrive in New York “have to study new abilities rapidly in the event that they wish to survive, and so they should adapt to an setting in contrast to the one from which they got here. In Flaco’s success they see their very own — or inspiration to proceed working towards their very own.”

All these had been causes that many individuals felt so protecting of the owl: a member of a species famend for its abilities as a predator, and but in Flaco’s case, an harmless of kinds, with no expertise fending for himself. His admirers fearful that he may crash right into a skyscraper window, run afoul of the Central Park coyote, or get hit by a automobile, a destiny met by Barry the Barred Owl in the summertime of 2021. The most important fear throughout his first days of freedom was that he wouldn’t know easy methods to hunt and will starve to dying — in spite of everything, he’d dined for a decade on deliveries of what one zoo affiliate described as Complete Meals-quality lifeless mice and rats.

However then Flaco defied everybody’s expectations. As longtime hen watcher Stella Hamilton identified, he was “like a fledgling” mastering the artwork of surviving, however a fledgling who compressed weeks of studying into a pair days. Regardless of a lifetime in captivity, the owl had in some way “remained wild inside.”

The photographer David Lei noticed Flaco on his first evening of freedom, trying considerably dazed and misplaced close to the Plaza Lodge, and he has chronicled the owl’s progress since. He watched Flaco’s first tentative hops from one tree to a different. And he witnessed Flaco not solely grasp the artwork of flight but in addition develop into an more and more assured hunter.

Eurasian eagle-owls are one of many world’s largest owls. And together with his practically six foot wingspan, Flaco thrilled observers at flyout each evening: a feline silhouette crouched on a tree limb, all of the sudden hovering into the nighttime sky, like an enormous pterodactyl taking wing throughout the park. Inside every week, he was changing into the apex predator he was born to be, proudly displaying off the rats he’d killed together with his naked talons.

There have been nonetheless perils — like consuming rats which have ingested rat poison. However Flaco’s new proficiency at looking started to alter folks’s enthusiastic about his future — rooting not for his protected return to the zoo, however for a brand new lifetime of freedom.

Within the Netherlands, the place Eurasian eagle-owls have been saved as pets, some have escaped. And in line with Marjon Savelsberg, an owl researcher there, plenty of these birds “return to the wild and study, identical to Flaco, easy methods to survive. And a few even nest and lift kids with wild Eurasian eagle-owls.”

When Flaco was residing on the zoo, he had been described by one longtime customer as a grumpy and barely pudgy owl — very similar to these of us caught at residence through the pandemic. However after solely two weeks in Central Park, he had develop into an athletic and good-looking prince, enthusiastically hooting his presence to assert his place within the metropolis or discover a attainable mate.

After two weeks of freedom, Flaco couldn’t be present in any of his favourite spots. When he was found, a day later, some two miles north within the park, many New Yorkers breathed a sigh of aid that he hadn’t suffered the destiny of Barry, or moved to the suburbs — he’d merely discovered a barely wilder place to hang around within the 843-acre park.

Flaco’s eagle-owl family members have tailored, on different continents, to residing in forests and on steppes, mountains, farmlands and in cities — one Eurasian eagle-owl even raised three owlets on the windowsill of an house constructing in a Belgian metropolis. And far the best way that Barry had introduced pleasure to New York through the darkest days of Covid, so Flaco gave a weary metropolis nonetheless attempting to come back again from the pandemic a heartening sense of resilience.

Michiko Kakutani is the writer of the guide “Ex Libris: 100+ Books to Learn and Re-Learn.” Comply with her on Twitter: @michikokakutani and on Instagram: @michi_kakutani

Science

L.A.'s newest dinosaur has its forever name

The people have spoken, and L.A.’s newest Jurassic-era resident has its forever name.

Dinosaur fans who responded to the museum’s request for input overwhelmingly chose to call the Natural History Museum’s new 70-foot-long sauropod “Gnatalie.”

More than 36% of roughly 8,100 participants in a public poll chose that name, which is pronounced “Natalie,” from among five options offered by the museum.

A rendering of the new dinosaur display at the Natural History Museum. Dinosaur fans who responded to a museum poll have decided to call the 70-foot-long sauropod “Gnatalie.”

(Frederick Fisher and Partners, Studio MLA, and Studio Joseph / NHMLAC)

The punny moniker is a reference to the relentless swarm of gnats that plagued paleontologists, students, museum staff and volunteers during the 13-year effort to unearth the dinosaur’s remains from a quarry in southeast Utah. Museum staff nicknamed the dinosaur Gnatalie while they were still digging it up, a process that lasted from 2007 to 2019.

The long-necked, long-tailed skeleton will be the focal point of the NHM Commons, a $75 million welcome center currently under construction on the southwest end of the museum in Exposition Park. Slated to open this fall, the Commons will offer gardens, an outdoor plaza, a 400-seat theater and a glass-walled welcome center that can be toured without a ticket.

“The efforts of hundreds of people contributed to what you see here, ground to mount,” said paleontologist Luis Chiappe, director of the Dinosaur Institute at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County.

The specimen appears to be part of a new species, similar to the Diplodocus, which will be scientifically named in the future. Thanks to celadonite minerals that replaced organic matter during the fossilization process, the mounted skeleton has a unique greenish-brown hue.

The skeleton is made up of about 350 fossils from six different animals whose bones washed into a river after death some 150 million years ago and commingled.

“We are delighted to see how many people voted and how much they loved our name for this unusual dinosaur,” said Lori Bettison-Varga, President and Director of the Natural History Museums of Los Angeles County.

Science

Mexico may legalize magic mushrooms. Will this traditional medicine lose its meaning?

Alejandrina Pedro Castañeda opened a brown paper package and pulled out a handful of magic mushrooms, which many residents of this Indigenous Oaxacan town tenderly refer to as “child saints” or “the little ones that sprout.”

Then she handed each of her six visitors — who had driven seven hours from Mexico City and paid up to $350 apiece for a healing retreat — a generously sized portion, prompting a few dubious looks.

It was nighttime, and the guests were sitting in a hut that was barely illuminated by two candles, making it difficult for them to see what they were about to eat.

Pedro Castañeda has used mushrooms in her healing practice for years and was comfortable stepping outside as the group crunched slowly in silence.

One person said the fungi tasted like stale popcorn. Another tasted dirt.

The healer returned a few minutes later.

“Now we’re starting the trip,” she said. “Let’s go to work.”

Indigenous communities in Mexico have long considered psychedelic mushrooms to be intermediaries to the spiritual world. But their growing popularity outside of Mexico has spurred a debate over who should have access to them and whether science and Indigenous medicine can or should be reconciled.

Magic mushrooms have been used in Mesoamerican religious rituals since pre-Hispanic times. But it wasn’t until the 1950s that a New York banker and mushroom enthusiast named R. Gordon Wasson made them famous — perhaps too famous — in the Western world.

(Alejandra Rajal / For The Times)

Some Indigenous healers are courting tourists. Scientists interested in their chemical properties have been studying mushrooms in hopes of developing treatments for depression and other mental health problems. And growing demand from recreational users has fueled a thriving black market.

Currently, the fungi can only be used in Indigenous rituals or in government-approved research. But a senate bill proposes making psilocybin, a psychedelic compound in the mushrooms, more widely available.

In addition to making psilocybin available to anyone with a doctor’s prescription, the bill would permit therapy that uses the actual mushroom that a government office of traditional medicine would help regulate. It also calls for scientific research on Indigenous medicine and providing compensation to Indigenous people for “patents” involving their traditions.

The bill’s supporters say that they’re trying to protect Indigenous medicine by making sure the traditional use of magic mushrooms is enshrined into law.

But the prospect of expanding the availability of magic mushrooms has created friction within Indigenous communities that have used them for centuries. Will the spirituality associated with this traditional medicine be lost?

::

Magic mushrooms have been used in Mesoamerican religious rituals since pre-Hispanic times. A mural from the ancient city of Teotihuacán, just outside Mexico City, shows the Toltec rain god Tlaloc with two figures alongside him holding mushrooms that have risen from where his raindrops fell. A Franciscan missionary documenting 16th century life in New Spain referred to the mushrooms as the “flesh of the gods.”

But it wasn’t until the 1950s that a New York banker and mushroom enthusiast named R. Gordon Wasson made Mexico’s magic mushrooms famous — perhaps too famous — in the Western world.

On a trip to Huautla, in southern Mexico, he ate mushrooms with Indigenous Mazatec healer María Sabina and wrote about the experience in a 1957 article for Life magazine titled “ Seeking the Magic Mushroom.” The story inspired thousands to travel to Huautla — some seeking out Sabina. The Mexican press described the foreigners as addicts, and the military ultimately set up a checkpoint on the road to Huautla to try to block the outsiders.

In July 1970, Reuters reported: “Hundreds of hippies are braving imprisonment and fines to penetrate this mushroom paradise in the State of Oaxaca, where the authorities are conducting a drive against mushroom eaters.”

Wasson said he felt guilty about the crowds in a New York Times op-ed published later that year. A “humble out-of-the-way” town had been overrun by “a torrent of commercial exploitation of the vilest kind.”

“The old ways are dead,” he wrote, “and I fear that my responsibility is heavy, mine and María Sabina’s.”

In an interview toward the end of her life, Sabina described how some outsiders would take the mushrooms “at whatever time and whatever place” and “don’t use them to cure themselves of a sickness.”

“From the moment the foreigners arrived to search for God,” she said, “the saint children lost their purity.”

In the mid-20th century, psilocybin was classified as a Schedule I substance in the U.S. — which put the kibosh on research. But interest in scientific research on mental health and psilocybin was rekindled in the 1990s.

::

Psilocybin is thought to boost neuroplasticity, the brain’s ability to form new neural connections, and research indicates that it may be successful in treating depression, anxiety and substance abuse. Parts of the United States have legalized or decriminalized the substance. (Oakland decriminalized magic mushrooms in 2019.)

“That plasticity enhancement may allow people to shift how their brain is functioning into a mode that’s more helpful, more adaptive, that’s going to promote mental health,” said Greg Fonzo, who co-directs the Center for Psychedelic Research & Therapy at the Dell Medical School at the University of Texas at Austin.

Alejandrina Pedro Castaneda, who has used mushrooms in her healing practice for years, hosts a mushroom ceremony once or twice a week.

(Alejandra Rajal / For The Times)

Some people who ingest magic mushrooms report overwhelming feelings of joy or the presence of family. Others have said they feel deeply sad or that they are having an out-of-body experience.

The risk of a lethal overdose is considered very low, Fonzo said. What’s more common is having a difficult experience or a “bad trip” due to anxiety.

Pedro Castañeda, who compares the bill with a birth certificate, supports the legislation, insisting the world must not forget that the Mazatecs, as well as other Indigenous communities, have preserved rituals with magic mushrooms for centuries.

“The medicine is not protected now. It’s out of control,” she said. “Everyone has it in their home, like cannabis,” she said, referring to black market purchases. “What we need is a record that says the Mazatecs are the custodians, the Mazatecs are the ones that for millennia have defended the medicine.”

But other Mazatecs in Huautla are worried about appropriation and misuse, that traditions associated with Indigenous culture will be disrespected as increasing numbers of people rush to pick up their prescriptions.

In an Indigenous mushroom ceremony, the healer will use mushrooms to communicate with their spiritual world to inquire about a patient’s illness. A patient may also experience revelations.

If the bill passes, “It’ll be taken like an aspirin,” said Isaias Escudero Rodriguez, a local doctor. It will no longer have the “spirituality that it carries for us.”

::

The push to legalize magic mushrooms in Mexico dates back to the early days of the pandemic. Alejandra Lagunes, 52, a senator in Mexico’s national congress, started to experience anxiety attacks that were reminiscent of the severe depression she suffered in her 20s. The depression from decades ago, she said, was resolved after she took ayahuasca — a psychoactive brew made from the Amazonian Banisteriopsis caapi vine — with an Indigenous healer.

Lagunes researched psychedelics and introduced legislation in November to increase access to magic mushrooms while recognizing the long tradition of Indigenous medicine. She hopes it opens the door for non-Indigenous Mexicans to learn from Indigenous practices.

The initiative has supporters at Mexico’s National Institute of Psychiatry, where scientists have government permission to investigate the potential therapeutic effects of magic mushrooms.

Jesús María González Mariscal, a clinical psychologist in Mexico City who has advised the senator, said much can be learned from traditional medicine, including the importance of companionship in Mazatec mushroom ceremonies. These ceremonies occur at night under the guidance of a healer with candles, flowers, incense and an altar with Catholic images. A patient’s family members may accompany them.

The result, Mariscal said, “is a space of care and protection so a person can explore their inner world in a context that’s safe, trustworthy and ethical” — and that’s what Mexico City psychotherapist Oscar O’Farrill is trying to teach his students.

O’Farrill runs a master’s and doctoral degree program affiliated with the National School of Psychologists and Experts of Mexico where his approximately dozen students listen to Indigenous guest speakers talk about traditional medicine. He schedules group therapies in his home, a two-story house where a large container on his kitchen counter has powder from lion’s mane, a non-psychedelic mushroom, that he takes with his morning coffee. Indigenous healers have led his students through ceremonies with mushrooms, peyote and bufo, the smoked secretions of a Sonoran desert toad.

“Psychiatry in this moment can’t understand what psilocybin is if it doesn’t understand all the aspects of the customs of Indigenous people,” he said. “Like it or not, the mushrooms have a spirit.”

But Eros Quintero, a biologist who co-founded the Mexican Society of Psilocybin in 2019, said he would have preferred that Indigenous communities were not singled out in the bill, that psilocybin simply be reclassified.

Indigenous people, he said, may not view illness through the prism of Western science. In Mazatec culture, for example, people may believe that a person fell ill because they walked through a cave where spirits are thought to reside or broke a communal rule.

“They have their own traditions and their own way of seeing things, and what we see is that there are few who are interested in what we’re interested in with psilocybin,” he said.

::

Huautla presents itself as a place for the mushroom-seeker.

Taxis decorated with images of small mushrooms speed up and down narrow mountain roads that are lined with tin-roofed houses. In the summer, when mushrooms are in season, locals wait by a bus terminal to offer the fungi to tourists. Prices vary, but a dozen pairs of mushrooms (they’re sold by the pair) may cost $25 and a ceremony can cost $90 or more. After mushroom season, the fungi are often preserved in jars with honey.

Several signs announce the home of the family of María Sabina — who died in poverty in 1985 but whose life has since been celebrated in Mexican culture. Her descendants, who live on the property where Sabina once resided, maintain a small museum filled with portraits of the healer and sell mushroom-themed crafts.

Anselmo García Martínez, a farmer and a great-grandson of Sabina, says he was about 6 when he tried mushrooms for the first time during a ceremony with relatives who were accompanying a sick family member. (Many other locals say they first consumed mushrooms as children.)

Like some other residents, he said he didn’t mind if mushrooms are allowed outside Indigenous rituals because the general public already has access to them through the black market.

But he issued a reminder: “For us, for the Mazatecs, it’s something sacred.”

Lagunes said she’s invited Indigenous people to the forums she has sponsored, and last year she posted a video on the social media platform X that showed her with several healers and indigenous people in Huautla. They presented her with a baton that she said she’d carry to “bring the voice and knowledge of ancestral medicine to the place that it deserves.”

But some opponents have said that the Mazatec people haven’t been properly consulted on whether the bill should move forward, reminding supporters that, for the moment, there is no infrastructure to make it happen. Santos Martínez, one of the founders of Caracol Mazateco, a civil society group focused on preserving Mazatec culture, agrees there hasn’t been enough outreach to the Mazatecs.

Martinez said his experiences with magic mushrooms transformed his life. As a medical student working at a clinic in the state of Puebla, he fell into a depression after seeing patients suffer from inadequate care. He returned to his community in Huautla, where he participated in mushroom ceremonies, hoping they would help him find direction in his life.

During the ceremonies he felt happy and had visions of family members, including his grandfather. “It was as if he was saying, ‘adelante, hijo,’” he said, or, “go forward, son.”

Francisco Javier Hernandez García, a Huautla healer who leads mushroom ceremonies for tourists almost daily at some points of the summer, fears that mushrooms will “lose respect” if they are legalized for therapy outside of the Indigenous context.

Like others, he spoke about mushrooms as carrying wisdom.

“They sprout because they are waiting for that person,” he said, referring to the one who will eat them. “They already know who carries problems.”

::

In mid-April, O’Farrill organized a trip for six people — including himself — to visit Pedro Castañeda for the healing retreat. Two people, a man who works for a Wall Street asset management firm and a woman training to guide people during mushroom trips, had flown in from the U.S. A mother and daughter, both psychologists, and a literary editor were from Mexico.

They spent three days at the home of Pedro Castañeda, who lives with eight dogs in a house that has several floors under construction. She hosts a mushroom ceremony for locals or tourists once or twice a week and said that the “great spirit” tells her how many mushrooms to give each person.

The members of O’Farrill’s group had individual therapy sessions with Pedro Castañeda in which she asked them about their insecurities. After her guests ate mushrooms, Pedro Castañeda asked several of them to sing. At one point, the editor began to suddenly cry, and the younger psychologist said she felt pain, prompting the healer to rigorously brush her with a feather in a cleansing ritual. A few minutes later, the psychologist said she was having visions of “injustice in jail.”

The next morning, the group hiked — mostly barefoot — the Mountain of Adoration, which the Mazatecs consider sacred.

At the top of the mountain, which overlooked Huautla, the healer gave each person cacao beans to leave as an offering, giving thanks for the previous night. They placed them on a tower of rocks jutting out from the mountain, next to many little mounds of cacao left earlier by other visitors.

Science

Opinion: Abortion foes lost Round One on mifepristone. Here's how their fight continues

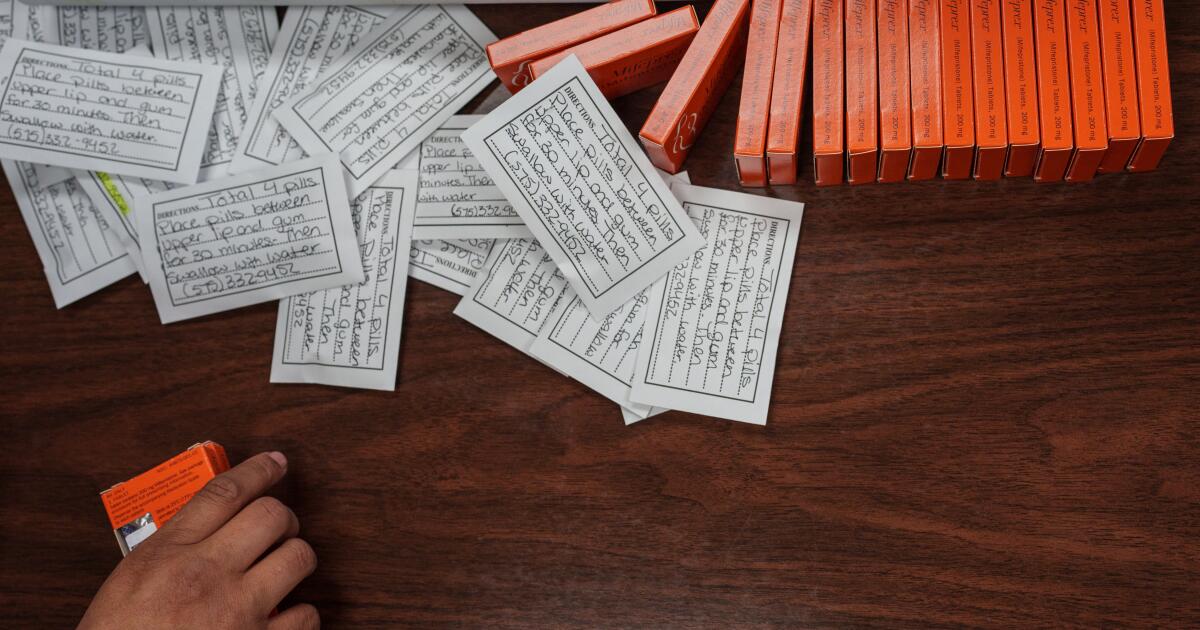

The Supreme Court’s mifepristone decision on June 13 put a stop to one challenge to the drug used in more than half of all abortions in the United States. But antiabortion groups are already preparing their next line of attack.

New groups of plaintiffs might try to establish that they have standing where the doctors in the Food and Drug Administration vs. Alliance for Hippocratic Medicine failed. But if Donald Trump wins the 2024 election, such lawsuits might be far less important to abortion foes: Conservatives already have detailed plans in place to use the executive branch to impose national limits on abortion.

The plaintiffs in FDA vs. Alliance made two sets of claims. First, they challenged the overall authority of the agency to approve and subsequently lift restrictions on mifepristone. The plaintiffs also argued that the FDA didn’t have the power to allow patients to receive the pills in the mail because the federal Comstock Act, a 19th century obscenity law, includes a ban on mailing and receiving abortion-related items.

In holding that the Alliance plaintiffs didn’t have standing to sue, the Supreme Court didn’t say a word about the merits of either of those claims. So it’s no surprise that other plaintiffs might try to bring them again before the justices. The leading contenders are the states of Kansas, Missouri and Idaho, which had sought to intervene in the case, a request turned away by the Supreme Court.

The states’ attorneys general have suggested that they will continue the litigation, with a new argument on standing. A preview of that claim came in the states’ petition to intervene: They argued that because their citizens could get mifepristone from doctors out of state, the states’ own interests were affected. Medicaid recipients who suffered mifepristone complications were imposing costs on state medical systems, they added, and the availability of mifepristone was making it difficult to make and enforce abortion bans.

There may be problems with the states’ case for standing too. Patients might experience complications if they take mifepristone, which might impose costs on the states. That doesn’t sound so different from the weak hypotheticals on which the Alliance plaintiffs relied. And what about Missouri and Idaho’s supposed sovereign interest in enforcing their abortion bans when other states allow it? The answer the court gave the Alliance doctors would seem to apply: “A plaintiff’s desire to make a drug less available for others does not establish standing to sue.”

Kansas’ case for standing is even more puzzling. Abortion is legal in Kansas until 22 weeks, albeit with restrictions. Barely more than a month after Roe was overturned, Kansans expressly voted against amending their state constitution to say there was no right to abortion. How will the state make the case that it is harmed by the approval of mifepristone when its own voters chose to preserve abortion access?

Whatever the fate of the case the Alliance doctors started, abortion foes and conservatives understand that the war against mifepristone and medication abortion can’t just depend on litigation. For example, Louisiana recently passed a law categorizing mifepristone and misoprostol, another drug used in medication abortion, as controlled substances, making it easier for the state to surveil patients, doctors and pharmacies and to punish anyone in possession of the drugs without a prescription. Idaho passed a so-called trafficking law that criminalizes those who help minors travel out of state or obtain abortion pills without parental consent.

But even these kinds of strategies may be far less important if Donald Trump wins a second term. The Heritage Foundation and a coalition of more than 100 conservative groups have laid out a detailed plan — known as Project 2025 — for a second Trump administration. The plan begins with a call for the FDA to “reverse its approval of chemical abortion drugs,” including mifepristone, or at a minimum, to eliminate the telehealth option for the drug.

Thousands of abortions can take place each month in states that ban the procedure because the telehealth option allows patients to get a prescription and get the pills by mail. With a Trump appointee as secretary of Health and Human Services, and one heading the FDA , the government might approach mifepristone differently without the pressure of a lawsuit. Some legal scholars argue that structural features of the federal Food and Drug Act could even allow the HHS secretary alone to override scientists at the FDA.

Then there is the ancient Comstock Act — moribund but still on the books. Gene Hamilton, a prominent figure in the first Trump administration, argues in the Project 2025 plan that the Department of Justice could simply dust off the 151-year-old law and start criminally prosecuting the mailing or receipt of mifepristone. If the Supreme Court buys this interpretation of the Comstock Act, despite its flaws, such an executive action would get around the thorny questions about standing raised in Alliance.

The Supreme Court deflected the Alliance case against mifepristone. We may well see it reappear in some form on the court’s docket next year. But whatever shape Alliance 2.0 takes, in the fight over a national abortion ban, it’s unlikely to be the main event.

Mary Ziegler is a law professor at UC Davis and the author of “Roe: The History of a National Obsession.”

-

News1 week ago

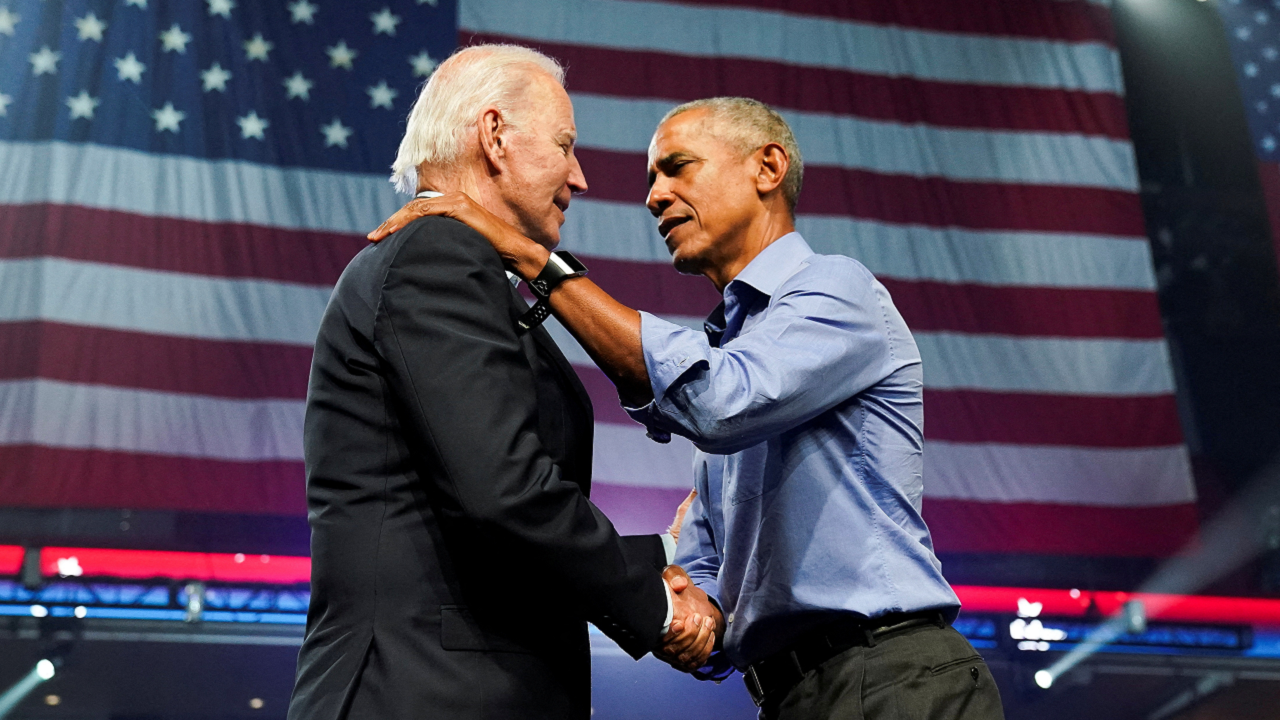

News1 week agoJoe Biden, Barack Obama And Jimmy Kimmel Warn Of Another Donald Trump Term; Star-Filled L.A. Fundraiser Expected To Raise At Least $30 Million — Update

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoIt's easy to believe young voters could back Trump at young conservative conference

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoRussia-Ukraine war: List of key events, day 842

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoSwiss summit demands 'territorial integrity' of Ukraine

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoProtesters in Brussels march against right-wing ideology

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoA fast-moving wildfire spreads north of Los Angeles, forcing evacuations

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoAl-Qaeda affiliate claims responsibility for June attack in Burkina Faso

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoJudge rules Missouri abortion ban did not aim to impose lawmakers' religious views on others