Science

Wastewater testing, vital in COVID-19 tracking, could help identify monkeypox spread

As wastewater testing continues to show helpful in estimating the unfold of the coronavirus, scientists once more are utilizing sewage to trace the newest public well being emergency: monkeypox.

In late June — a few month after the primary California case was confirmed — monkeypox DNA was detected in wastewater in San Francisco, in accordance with the WastewaterSCAN coalition, a gaggle of scientists who’ve been testing sewage for the presence of the coronavirus since 2020.

The group just lately confirmed the presence of the monkeypox virus in Los Angeles County waste.

“It helps perceive how widespread that is,” mentioned Stanford civil and environmental engineering professor Alexandria Boehm, one of many lead researchers on the WastewaterSCAN staff.

She mentioned COVID-19 sewage testing has been notably helpful throughout “the onset section,” or instantly after a brand new variant has been recognized nevertheless it’s unclear the extent of its presence. Public well being officers can use the data to theorize how nice the unfold might turn into.

“We’re kind of in that [phase] for monkeypox now,” Boehm mentioned.

Monkeypox DNA was first detected in Los Angeles County wastewater July 31, about 20 days after the WastewaterSCAN group expanded its monkeypox testing past the Bay Space to nearly 40 different amenities nationwide — together with in L.A. — in accordance with information from the group.

Samples from L.A.’s Joint Water Air pollution Plant in Carson, which serves about 4 million residents and companies, confirmed a small presence of the monkeypox virus July 31 and for 3 days throughout the first week in August, in accordance with WastewaterSCAN information. The virus since has not been detected there, regardless of rising monkeypox circumstances in Los Angeles County.

By comparability, monkeypox DNA has been detected nearly day-after-day since June 27 at two wastewater amenities in San Francisco — and at a lot larger ranges than in L.A. County.

Nonetheless, Boehm mentioned that doesn’t imply there’s no more monkeypox in Los Angeles County; it’s simply troublesome to detect among the many huge pattern dimension.

As a result of the L.A. wastewater facility serves such a large variety of individuals “it’s important to take into consideration the sensitivity of detecting monkeypox relative to the incident fee within the inhabitants,” Boehm mentioned. “Simply since you don’t detect monkeypox, doesn’t imply there’s no one [in that waste watershed] with monkeypox.”

The 2 amenities in San Francisco serve a a lot smaller inhabitants, about 100,000 residents every.

Whereas each Los Angeles and San Francisco have seen a fast rise in monkeypox circumstances in latest weeks, the totals are nonetheless solely a fraction of every county’s inhabitants: about 600 in San Francisco amongst fewer than 1 million residents and roughly 1,000 in L.A. County amongst 10 million residents, in accordance with every county’s public well being departments.

“We’re doing [wastewater] surveillance for monkeypox, and it was solely simply recognized,” the Los Angeles Division of Public Well being mentioned in a press release. “It took longer to establish right here than in some locations most definitely as a result of we have now a big inhabitants relative to the variety of circumstances. Wastewater surveillance is comparatively new and considerably investigational.”

It was not instantly clear whether or not the L.A. County well being division plans to develop monkeypox testing in wastewater or how it will use the information. The county has been monitoring wastewater for the coronavirus for months, together with on the Joint Water Air pollution Plant, in addition to on the Hyperion Water Reclamation Plant in Playa Del Rey and amenities close to Lancaster and Malibu.

When at-home COVID-19 testing started to restrict the flexibility to watch case counts, L.A. County public well being officers usually used wastewater information to trace transmission tendencies — one issue that performed a job in a choice to not implement one other indoor masks mandate.

“It’s useful to have this extra lens into the epidemiology and dynamics of illness as a result of it doesn’t depend on behaviors of individuals or testing,” Boehm mentioned. “There’s sort of a health-equity part.”

She mentioned wastewater information can assist inform public well being selections, corresponding to the place to focus on data, clinics or therapy.

The scientists behind WastewaterSCAN name the information on viruses “invaluable,” having already discovered monkeypox in 22 California wastewater amenities, from San Diego to Sacramento, in addition to at 9 amenities in seven different states.

There’s not but a nationwide database to trace monkeypox in waste, such because the CDC does for COVID-19, however Boehm mentioned she’d wish to see the testing develop. Her staff is also working to check sewage for influenza A and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), which she hopes can proceed to assist reply questions on viral transmission.

She mentioned she’d just like the wastewater testing, which has been discovered to be extraordinarily correct, for use to tell care, therapy and even vaccine growth of present viral outbreaks — in addition to future ones.

“I’m a scientist, so I’m simply curious how far we will take this,” Boehm mentioned. “Its’ turning out to be a very attention-grabbing and kind of superb useful resource for understanding public well being.”

Science

What the Golden Ratio Says About Your Bellybutton

Science

COVID 'razor blade throat' rises as new subvariant spreads in California

• COVID rising in wastewater in parts of California

• New subvariant, ‘Nimbus,’ increasingly dominant nationally

• Concerns rise about Trump’s appointees making vaccine access more difficult

COVID-19 appears to be on the rise in some parts of California as a new, highly contagious subvariant — featuring “razor blade throat” symptoms overseas — is becoming increasingly dominant.

Nicknamed “Nimbus,” the new subvariant NB.1.8.1 has been described in news reports in China as having more obvious signs of “razor blade throat” — what patients describe as feeling like their throats are studded with razor blades.

Although “razor blade throat” may seem like a new term, the description of incredibly painful sore throats associated with COVID-19 has emerged before in the United States, like having a throat that feels like it’s covered with shards of glass. But the increased attention to this symptom comes as the Nimbus subvariant has caused surges of COVID-19 in other countries.

“Before Omicron, I think most people presented with the usual loss of taste and smell as the predominant symptom and shortness of breath,” said Dr. Peter Chin-Hong, a UC San Francisco infectious-disease expert. But as COVID has become less likely to require hospitalization, “people are focusing on these other aspects of symptoms,” such as an extraordinarily painful sore throat.

Part of the Omicron family, Nimbus is now one of the most dominant coronavirus subvariants nationally. For the two-week period that ended June 7, Nimbus comprised an estimated 37% of the nation’s coronavirus samples, now roughly even with the subvariant LP.8.1, probably responsible for 38% of circulating virus. LP.8.1 has been dominant over the past few months, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The Nimbus subvariant has also been increasing since May in California, the state Department of Public Health said in an email to the Los Angeles Times. Projections suggest the Nimbus subvariant comprises 55% of circulating virus in California, up from observations of just 2% in April, the agency said Friday.

“We are seeing some indicators of increased COVID-19 activity, including the rise of the NB.1.8.1 variant, elevated coronavirus levels in wastewater, and an uptick in the test positivity rate,” Dr. Elizabeth Hudson, regional chief of infectious diseases for Kaiser Permanente Southern California, wrote in an email to The Times.

“Wastewater surveillance across Southern California shows variability: Santa Barbara watersheds are reporting moderate-to-high levels, Ventura and Los Angeles counties are seeing low-to-moderate levels, Riverside is reporting low levels, while San Bernardino is experiencing high activity,” Hudson said.

While viral concentrations remain relatively low, Los Angeles County has observed an increase in coronavirus levels in sewage, the local Department of Public Health told The Times. For the week that ended May 30 — the most recent available — viral levels in wastewater rose by 13% versus a comparable period several weeks earlier.

In addition, there is a slight increase in the rate in which COVID surveillance tests are turning up positive in L.A. County. For the most recent week, 5% of COVID surveillance tests showed positive results for infection, up from 3.8% in early May. COVID-related visits to the emergency room remain low in Los Angeles County.

There were still low rates of COVID-19 illness in San Francisco, the local Department of Public Health said.

Yet coronavirus levels in wastewater in Northern California’s most populous county, Santa Clara County, are starting to increase, “just as they have over past summers,” the local Public Health Department said in an email to The Times. As of Friday, coronavirus levels in the sewershed of San José was considered “high.” Viral levels were “medium” in Palo Alto and “low” in Sunnyvale. Nimbus is the most common subvariant in the county.

Across California, coronavirus levels in wastewater are at a “medium” level; the last time viral levels were consistently “low” was in April, according to the state Department of Public Health’s website.

“Future seasonal increases in disease levels are likely,” the California Department of Public Health said in an email to The Times Friday.

The uptick in COVID comes as many medical professional organizations and some state and local health officials are objecting to the Trump administration’s recent moves on vaccine policy, which some experts fear will make it more difficult for people to get vaccinated against COVID-19 and other diseases.

Federal officials in May weakened the CDC’s official recommendations from recommending the COVID vaccine to everyone age 6 months and up. The CDC now offers “no guidance” on whether healthy pregnant women should get the COVID vaccine, and now asks that parents of healthy children talk with a healthcare provider before asking that their kids get inoculated.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists issued a rebuke of the changing vaccine recommendations for pregnant women, accusing the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services — led by the vaccine-skeptic secretary, Robert F. Kennedy Jr. — of “propagating misinformation.” The American Pharmacists Assn. wrote that dropping the vaccine recommendation for pregnant women did “not appear to be based on the scientific evidence provided over the last few years.”

And an open letter by 30 organizations specializing in health — including the American Medical Assn. — said that “we must continue to prioritize high levels of COVID-19 vaccine coverage in pregnant patients to protect them and their infants after birth.”

Chin-Hong said he recommends pregnant women get vaccinated “one million percent.”

“The data are incredibly clear that pregnant women do have a higher rate of complications, hospitalization and premature births when they did not get vaccinated [against COVID] compared to the ones that did,” said Dr. Yvonne Maldonado, an infectious-disease expert at Stanford University. The vaccines also help newborns, as antibodies generated by the mom-to-be cross the placenta, and can protect the newborn for a certain number of months, she said.

That’s essential protection, given that newborns can’t be vaccinated under 6 months of age, Maldonado said. If newborns are infected, they have relatively high rates of hospitalization — as high as those age 65 and over, Maldonado said.

Then, last week, Kennedy abruptly fired all members of a highly influential committee that advises the CDC on vaccine policy. In an op-ed to the Wall Street Journal, Kennedy criticized the previous members of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, founded in 1964, as being “plagued with persistent conflicts of interest and has become little more than a rubber stamp for any vaccine.”

Maldonado, a professor in pediatric infectious diseases and epidemiology, was one of the fired vaccine advisors. She called their mass dismissal unprecedented in the history of the ACIP.

“We are absolutely in uncharted territory here,” Maldonado said. “I think it’s going to be really hard to understand what vaccines are going to go forward. … They’re also going to review the entire vaccination schedule.”

In general, routine review of vaccine schedules are a good thing, and prior reviews have concluded that the current recommended shots are safe and effective, Maldonado said. But the criteria being circulated by recently appointed federal officials “could actually wind up refusing to recommend, say, measles vaccine or HPV vaccine, because I’ve seen some of the misinformation that has been out there about some of these vaccines. …

“And if any of that is accepted as truth, we could wind up losing some of these vaccines,” Maldonado said.

“The question, then, is: ‘Would those vaccines disappear?’ … Hard to know,” she said. But it’s also possible that federal officials could begin to stop paying for certain vaccines to be administered to children of low-income families.

She rejected Kennedy’s characterization of the committee as a rubber stamp for vaccine makers. “Generally, a decision to not pursue a vaccine happens usually well before anything gets to a vote,” Maldonado said.

A joint statement by the governors of California, Oregon and Washington condemned Kennedy’s dismissal of the vaccine advisors as “deeply troubling for the health of the nation” and defended the fired vaccine advisors as having been “carefully screened for major conflicts of interest.”

“We have grave concerns about the integrity and transparency of upcoming federal vaccine recommendations and will continue to collaborate to ensure that science and sound medicine prevail to prevent any loss of life,” Gov. Gavin Newsom said in a statement Thursday.

Traditionally, the advisory committee’s recommendations on who should get vaccinated were adopted by the director of the CDC.

“It was one of the most depressing weeks in American health … a dark period for everyone right now, and demoralizing,” said Chin-Hong, of UC San Francisco. “It’s very destabilizing.”

The American Academy of Pediatrics called the purge of the vaccine advisors “an escalating effort by the administration to silence independent medical expertise and stoke distrust in lifesaving vaccines.” Kennedy’s handpicked replacements include people known for their criticism of vaccines, the Associated Press reported.

The mass firing “likely puts vaccine access and insurance coverage at serious risk,” the L.A. County Department of Public Health said in a statement. “It corrodes trust in the recommended schedule for vaccines, not only by the public, but by medical providers who rely on the ACIP for science-based, apolitical guidance.”

The departments of public health for California, Oregon and Washington said they “continue to recommend all individuals age 6 months and older should have access and the choice to receive currently authorized COVID-19 vaccines, with an emphasis on protecting higher risk individuals, such as infants and toddlers, pregnant individuals, and others with risks for serious disease.”

The L.A. County Department of Public Health said in a statement that, “at this time in Los Angeles County, current vaccine recommendations for persons aged 6 months and older to receive the COVID-19 vaccine remain in effect and insurance coverage for COVID-19 vaccines is still in place.”

Science

Strangers in the middle of a city: The John and Jane Does of L.A. General Medical Center

He had a buzz cut and brown eyes, a stubbly beard and a wrestler’s build.

He did not have a wallet or phone; he could not state his name. He arrived at Los Angeles General Medical Center one cloudy day this winter just as thousands of people do every year: alone and unknown.

Some 130,000 people are brought each year to L.A. General’s emergency room. Many are unconscious, incapacitated or too unwell to tell staff who they are.

Nearly all these Jane and John Does are identified within 48 hours or so of admission. But every year, a few dozen elude social workers’ determined efforts to figure out who they are.

Too sick to be discharged yet lacking the identification they need to be transferred to a more appropriate facility, they stay at L.A.’s busiest trauma hospital for weeks. Sometimes months. Occasionally years.

That’s an outcome no one wants. And so hospital staff did for the buzz cut man what they do once every other possibility is exhausted.

Social workers cobbled together the tiny bit of information they could legally share: his height and weight, his estimated age, his date of admission, the place where he was found. They stood over his hospital bed and took his photograph.

Then they asked the 10 million people of Los Angeles County: Does anyone know who this is?

This unidentified patient arrived at L.A. General on Feb. 6 after being found unconscious in East Hollywood.

(Los Angeles General Medical Center)

-

Share via

Just before 8 a.m. on Feb. 16, paramedics responded to a medical emergency at 1037 N. Vermont Ave.

The man was face-down on a stretch of sidewalk lined with chain-link fences and sandbags, near a public restroom and the entrance to the Vermont/Santa Monica subway stop. Pink scrape marks blossomed above and below his right eye.

Paramedics estimated he was about 30 years old. Hospital staff guessed 35 to 40.

He had no possessions that might offer clues: no phone, no wallet, no tickets or receipts crumpled in his pockets.

He could not state his name or answer any questions. The hospital admitted him under a name the English-speaking world has used for centuries when a legal name can’t be verified: John Doe.

The vast majority of patients admitted as John Does leave as themselves. The unconscious wake up. The intoxicated sober up. Frantic relatives call the hospital looking for a missing loved one, or police arrive seeking their suspect.

None of these things happened for the man from North Vermont. When he finally opened his eyes, his language was minimal: a few indistinct words — possibly English, possibly Spanish — and nothing that sounded like a name.

Social workers wrote down everything they knew for sure about their patient: his height (4 feet, 10 inches), his weight (181 pounds), the color of his eyes (dark brown).

Then they started following the trail that typically leads to identification.

The ambulance crew didn’t recognize him, and the run sheet — the document paramedics use to record patients’ condition and care — had no revelatory details.

They checked Google Maps. Any nearby shelter whose manager they could call to ask about a missing resident? Nope. Was there an apartment building whose residents might recognize his photo? Nothing.

A second photo L.A. General released to the public in search of a name or next of kin for this unidentified patient found in East Hollywood.

(Los Angeles General Medical Center)

They clicked through county databases. His details didn’t align with any previously admitted hospital patient, or anyone in the mental health system. No missing-persons report matched his description; social workers couldn’t find a mention of someone like him in any social media posts.

An anonymous patient is an administrative problem. It’s also a safety concern. If a patient can’t state their name, they probably also can’t say if they have life-threatening allergies or are taking any medications, said Dr. Chase Coffey, who oversees the hospital’s social work team.

“We do our darndest to deliver safe, effective, high-quality care in these scenarios, but we run into limits there,” he said.

Federal law requires hospitals to guard patient privacy zealously, and L.A. General is no exception. But given that virtually every hospital deals with unnamed patients, California carves out an exception for unidentified people who can’t make their own healthcare decisions. In such instances, hospitals can go public with information that could locate their patient’s next of kin.

On March 3, nearly two weeks after the man’s arrival, a press release went live on the county’s website and pinged in the inboxes of reporters across the region.

“Los Angeles General Medical Center, a public hospital run by the L.A. County Department of Health Services, is seeking the media and public’s help in identifying a patient,” the flier said. In the photograph the man gazed up from his hospital bed, eyes fixed somewhere past the camera, looking as lost as could be.

The buzz cut man from North Vermont was not the only Doe in the hospital’s care.

On the same March 3 morning, the county asked for help identifying a wisp-thin elderly man with a grizzled beard and swollen black eye who’d been found in Monterey Park’s Edison Trails Park.

Three days later, it sent out a bulletin for a gray-haired Jane Doe picked up near Echo Park Lake. In her photo she was unconscious and intubated, a bruise forming on her forehead, wires curling around her.

L.A. General seeks identification for a female patient who arrived in late May.

(Los Angeles General Medical Center)

By the end of the month, L.A. General would ask the public to identify four more men and women found alone in parks and on streets across the county, people whose cognitive state or medical condition left them unable to speak for themselves.

All of the hospital’s Does are found in L.A. County. That doesn’t mean they live here.

L.A. General is 2 miles from Union Station, where buses and trains deposit people traveling from all over North America. A few years ago, Coffey and social work supervisor Jose Hernandez found themselves trying to place an elderly couple from Nevada, both suffering from cognitive decline, who arrived at the station and couldn’t recall who they were or where they meant to go.

Fingerprinting is rarely an option. The federal fingerprint database can be accessed only for patients who are dying or are the subject of a police investigation, hospital staff said.

Even if those criteria are met, the database will only yield a name if the person’s fingerprints are already in the system. And even that’s not always enough.

Late last year, law enforcement ran the prints of an unidentified female patient who had been involved in a police incident. The system returned a name — one the patient adamantly insisted was not hers.

“Now the question is, is she confused? Do we have the wrong fingerprints-to-name match? Is there a mismatch? Is there a person using a different identity?” said Coffey. “Now what do we do?”

In end-of-the-rope scenarios such as this, the hospital turns to the public.

The press releases are carefully phrased. The hospital can disclose just enough information to make the patient recognizable to those who know them, but not a word more. Federal laws forbid references to the patient’s mental health, substance use, developmental disability or HIV status.

The hospital is trying to find next of kin for a 26-year-old man admitted in March.

(Los Angeles General Medical Center)

The releases are posted on the county’s website and social media channels. Local media outlets often publicize them further.

In “the best outcome that we get, we send [the notice] out and we get a hit within a couple of days. We start getting calls from the community saying, ‘Oh, we know who this patient is,’” Hernandez said.

About 50% of releases lead to such positive outcomes. For the other half of patients, the chance of being named gets a little smaller with every day that the phone doesn’t ring.

“If we don’t know who you are after a month, that’s when it becomes decreasingly likely that we’re going to figure it out,” said Dr. Brad Spellberg, the hospital’s chief medical officer.

On April 9, nearly two months after the buzz cut man’s arrival at L.A. General, the hospital sent out a second release about him. His scrapes had healed. His black hair was longer. His stubble had grown into a wispy beard.

“Patient occasionally mentions that he lives on 41st Street and Walton Avenue,” the release said. “Primarily Spanish speaking.” But he still had no name.

It is possible for a person in this situation to be stuck at L.A. General for the rest of their lives.

One man hit by a car on Santa Monica Boulevard in January 2017 lived for nearly two years with a traumatic brain injury before dying unidentified in the hospital. As of late 2024, a few Does had been there for more than a year.

1. This woman, believed to be 55, was found outside Los Angeles General Medical Center. 2. This patient, who was found in Pasadena, has a tattoo of a small cross on his left forearm and small star tattoo on his left bicep. 3. This patient, believed to be about 50 years old, was found on East 5th Street in downtown Los Angeles. (Los Angeles General Medical Center)

If a patient has no identity, L.A. General can’t figure out who insures them. And in the U.S. healthcare system, not having a guarantee of payment is almost worse than not having a name.

Skilled nursing facilities, group homes and rehabilitation centers won’t take people who don’t have anyone to pay for them, Spellberg said. The county Public Guardian serves as a conservator for vulnerable disabled residents, but can’t accept nameless cases.

Unless a patient recovers sufficiently to check themselves out, they are stuck in a lose-lose scenario. They can’t be discharged from L.A. General, whose 600 beds are desperately needed by the county’s most critically ill and injured, but also can’t move on to a facility that provides the care they need.

“We’re the busiest trauma center west of Texas in the United States,” Spellberg said. “If our bed is taken up by someone who really doesn’t need to be in the [trauma] hospital but can’t leave … that’s a bed that’s not available for other patients who need it.”

L.A. General is staffed to handle crises, not long-term care of people with dementia or traumatic brain injuries.

Bedbound patients could get pressure sores if they aren’t turned frequently enough. Mobile patients could wander the hospital’s corridors, or fall and injure themselves.

“You’re trapping the patient in the wrong care environment,” Spellberg said. “They literally become a hostage in the hospital, for months to years.”

The man found in Edison Trails Park eventually left the hospital. So did the gray-haired woman, whose name was at last confirmed.

The man from North Vermont is still at L.A. General, his identity as much a mystery as the day he arrived four months ago.

The Does keep coming: An elderly man found near Seventh and Flower streets. A young man found near railroad tracks. A man with burn injuries and a graying beard; another unconscious and badly bruised.

All sick or injured, all separated from their names, all their futures riding on a single question: Does anyone know who this is?

If you have information about an individual pictured here, contact L.A. General’s Social Work Department from 8 a.m. to 5 p.m. Monday through Friday at (323) 409-5253. Outside of those hours, call the Department of Emergency Medicine’s Social Work Department at (323) 409-6883.

-

West1 week ago

West1 week agoBattle over Space Command HQ location heats up as lawmakers press new Air Force secretary

-

Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoThere are only two commissioners left at the FCC

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoA former police chief who escaped from an Arkansas prison is captured

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoUkraine: Kharkiv hit by massive Russian aerial attack

-

Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoXbox console games are suddenly showing up inside the Xbox PC app

-

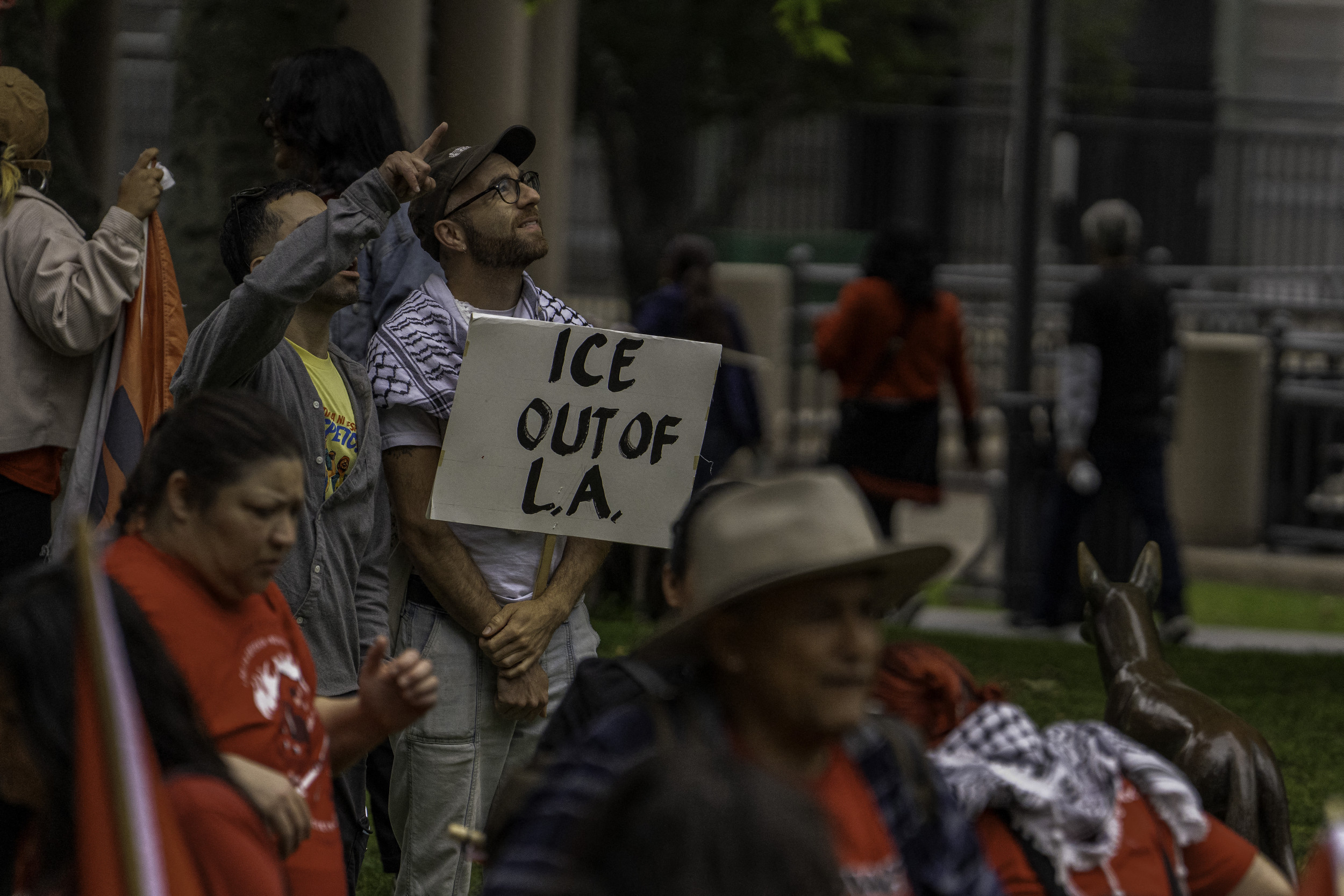

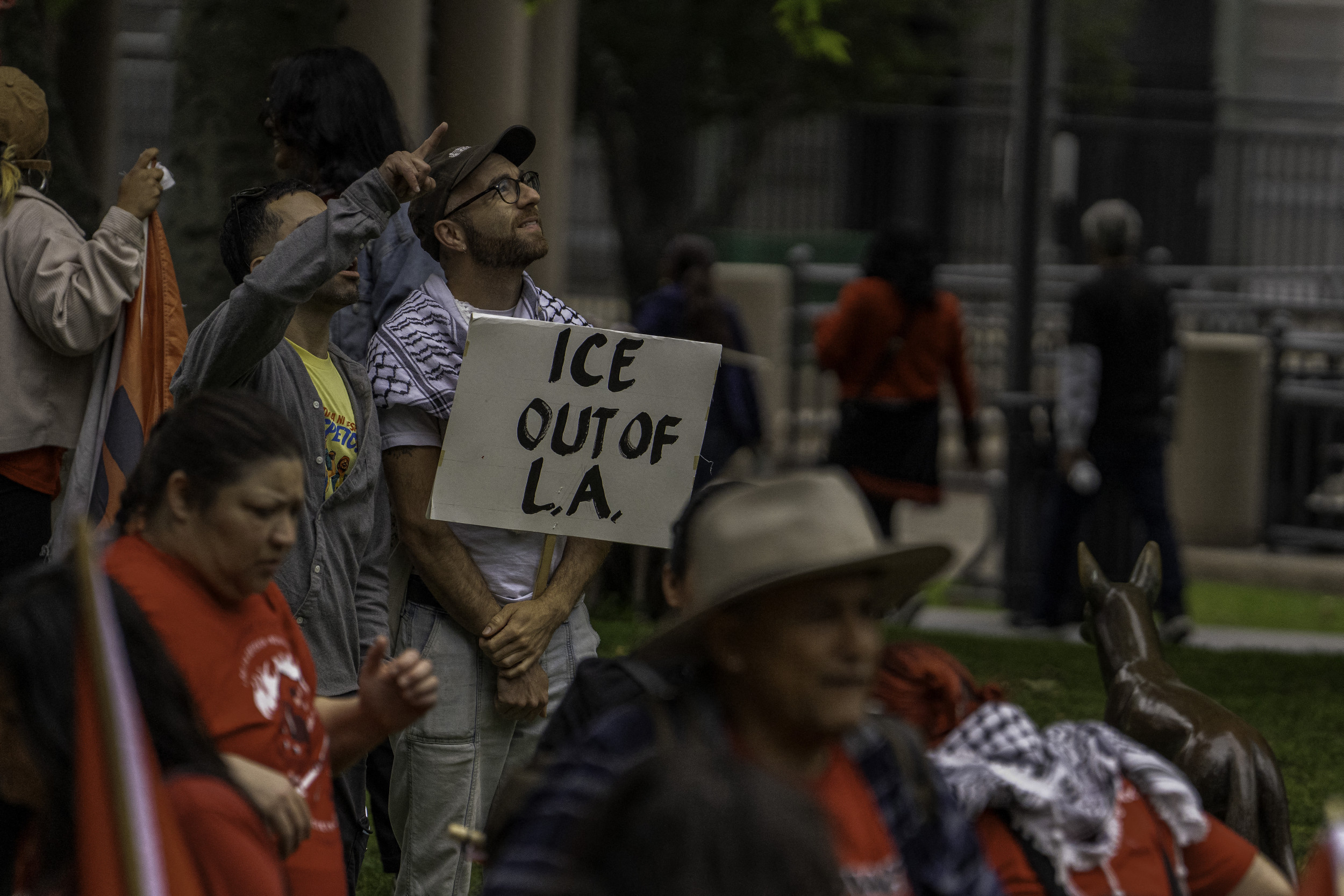

News1 week ago

News1 week agoMajor union boss injured, arrested during ICE raids

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoColombia’s would-be presidential candidate shot at Bogota rally

-

Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoMassive DMV phishing scam tricks drivers with fake texts