Science

Surrogate otter mom at Long Beach aquarium is rehabilitating pup 'better than any human ever can'

Millie, a fatigued mother of an infant, was ready for a nap.

So she grabbed her baby, flipped it around, threw it on her belly and started grooming its tail — a soothing behavior.

Aggressive and impactful reporting on climate change, the environment, health and science.

Millie, a sea otter, is rearing what could be the Aquarium of the Pacific’s first orphaned pup to return to the wild. As a surrogate mom, she’s teaching her adopted baby everything she needs to know to fend for herself — in the hopes she can hack it in the ocean in a few months.

“It’s all instinctual, and she’s doing it way better than any human ever can,” said Megan Smylie, sea otter program manager at the Long Beach aquarium.

Their pairing isn’t all about cuddles and relaxation. Just before Millie decided it was nap time, the pup known as 968 was practicing manipulating a crab shell, one of the skills she’d need to survive in the ocean. She’d also need to master foraging for food and grooming her thick, insulating coat.

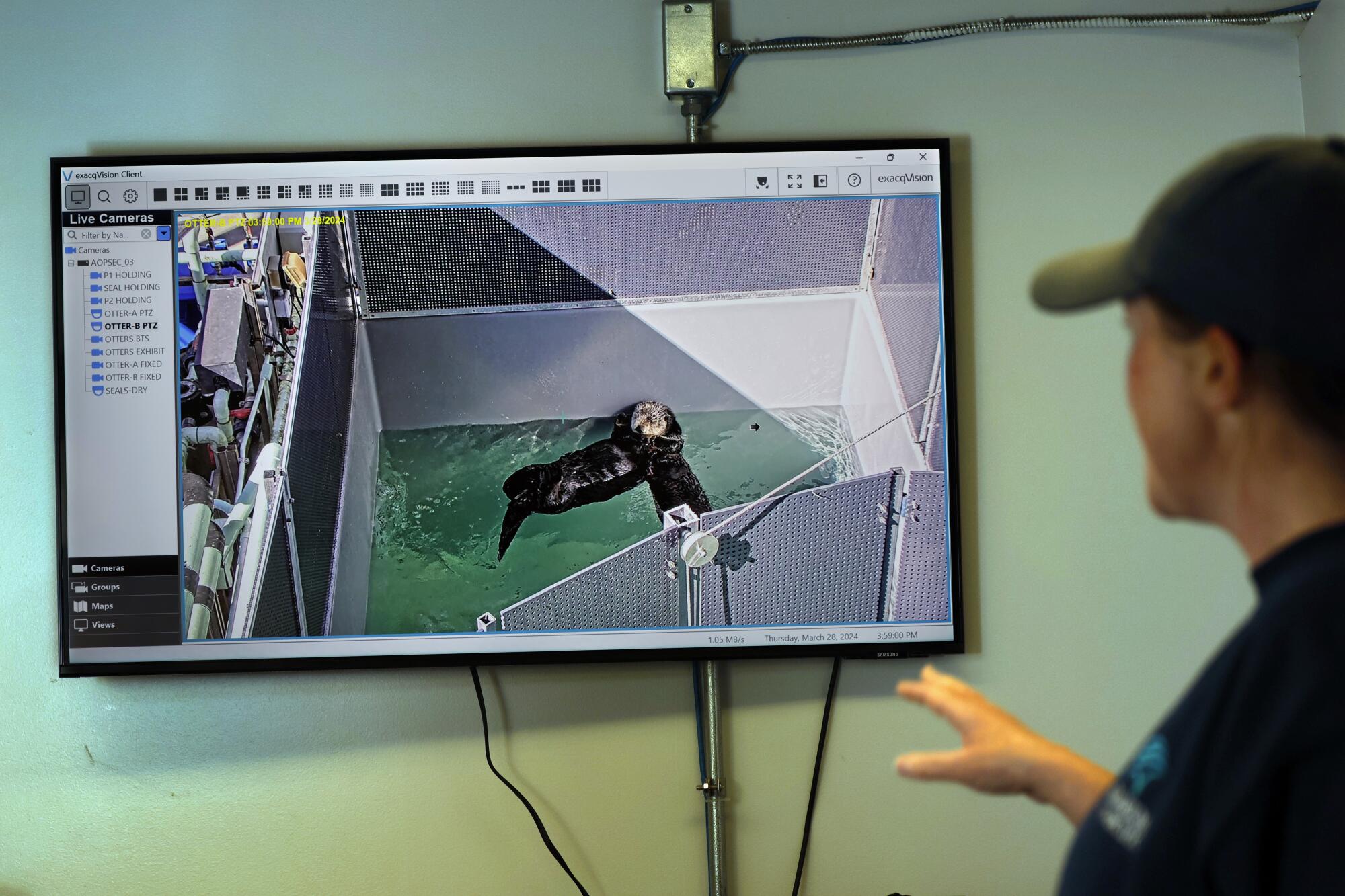

Megan Smylie, sea otter program manager at the Aquarium of the Pacific, watches Millie and pup 968 on a screen. The aquarium is limiting the young otter’s exposure to humans to improve her chances of survival if released into the wild.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

Climate warriors in limbo

Unlike seals and sea lions, otters need to be taught basic survival skills. And, conservationists say, their survival is a high priority.

They’re so important to maintaining a healthy coastal ecosystem that they’re often called “climate warriors.” Otters chow down on urchins, which voraciously devour kelp. When urchins are kept in check, kelp forests flourish — sequestering carbon and providing food and shelter for fish, shellfish and other life.

Once thought to be extinct, southern sea otters’ rebounding population has stalled, stymied by shark bites and parasites. They dive, hunt and float from south of San Francisco to just north of Santa Barbara, a fraction of their historical range, making them vulnerable to localized catastrophes such as oil spills.

There are now about 3,000 southern sea otters. That’s heartening relative to the total in the late 1930s — about 50 — but a far cry from their 150,000-300,000 peak in the early 18th century. Hunting nearly eradicated them, while protections helped them claw back. The population has stabilized over the last five years.

Sometimes baby sea otters get separated from their mothers, who might fall victim to a predator or get swept away during a storm. If they aren’t reunited or rescued by people, the outlook isn’t good; most baby otters can’t survive long alone.

With the recent rollout of its otter surrogacy program, the Aquarium of the Pacific joined the Monterey Bay Aquarium’s efforts and has roughly doubled the capacity in California to rehabilitate orphan otters using adoptive moms — a method research has shown gives the otters the best chance (about 75%) of being wild again.

It’s a promising expansion, but still falls short of the need. Most years, more otters strand than the Long Beach and Monterey facilities can accommodate, according to staffers.

“So growing this program is going to be a pretty high priority for people that are invested in otter conservation,” Smylie said.

The otters the public can see at the Aquarium of the Pacific provide plenty of cuteness. (Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

Hello 968

Toward the end of January, a passerby found 968 stranded north of Santa Cruz. Sometimes an otter mom can be heard calling out for her baby somewhere nearby. But the pup was all alone.

She was about 8 weeks old, and still dependent on her mother for survival. (Otter dads are not in the picture.)

So she was taken to the Monterey Bay Aquarium, where all sea otter pups stranded in California pass through. Her number denotes that she’s the 968th otter to enter the aquarium’s rehabilitation program.

Pups aren’t just tossed back into the surf; they must go through rehabilitation to learn how to be an otter.

So began her long, and still uncertain, path back to the chilly coastal waters of Central California.

Teaching an otter how to be an otter

The Aquarium of the Pacific’s foray into otter surrogacy is an outgrowth of the pioneering efforts of the Monterey Bay Aquarium, which started rescuing otter pups in the mid-1980s, even before it officially opened its doors.

The surrogacy concept emerged early on, said Jessica Fujii, manager of the Monterey Bay Aquarium’s sea otter program. In the wild, through their research program, staff “saw adoptions occurring naturally; it wasn’t common, but it had been seen,” she said. “So there was this thought that the strong maternal instincts that sea otters have could translate to the surrogacy in care.”

But an early attempt, in 1987, wasn’t successful. So for a time staffers tried to act as the pup’s mom, even swimming and diving alongside it in a big tidepool near the aquarium to teach it to forage.

To keep rehabilitating otters from becoming too comfortable with humans, aquarium staff members such as Brett Long watch them remotely.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

While otters raised this way were able to hunt, they didn’t always socialize properly, said Brett Long, senior director of birds and mammals at Aquarium of the Pacific. Many were too comfortable with people.

“We are very good at keeping them alive and very good at keeping them healthy,” Long said. “What we’re not very good at is teaching them how to be an otter back out there.”

Then, in 2001, the Monterey Bay Aquarium paired an orphaned pup with Toola, a stranded female otter who’d had a stillborn. The pair bonded.

From there, the aquarium tried pairing orphans with otters that hadn’t been “primed” by a recent birth. More success.

They continued refining the methods, distancing humans from the caretaking process as much as possible. Caretakers wear disguises reminiscent of Darth Vader’s getup during feedings — so they’re not recognized as people. Panels are put around their pools to block the sight of humans, and the otters are monitored remotely. Releasable otters are also never placed in aquarium displays where throngs of visitors can “ooh” and “ahh” at them.

Researchers previously thought “experience and knowledge of the ocean was the most important part” of the rearing process, Fujii explained. “And what we since learned is that really that social aspect and that kind of identification as, ‘You’re an otter,’ was really key.”

Over two decades, 70 pups have passed through the Monterey aquarium’s surrogacy program. Ten mature female otters did their part as adoptive moms. A study found the rewilded otters contributed to population growth in an estuary called Elkhorn Slough. In 2002, when the aquarium began its releases, there were only about 20 otters in the estuary. By 2016, there were more than 100.

In late February 2020, the Long Beach aquarium announced it was joining the surrogacy program as a partner and welcoming Millie, who is now 7. The pandemic around the corner delayed the program’s rollout, and it wasn’t until September 2023 that the permit was approved. But they still had to wait for a stranded otter to put Millie’s surrogacy skills to the test.

A long road home

After a three-week stabilization period, 968 was driven from Monterey to Long Beach. During the roughly six-hour drive, she had ice to munch on and cool air piped in.

When 968 met Millie in February, it wasn’t familial love at first sight — at least on the pup’s end.

She stranded later than most pups, meaning she may have had some memory of her biological mom, experts said.

“And so the first time it met Millie, it was like, ‘You’re not my mom.’ And Millie, fortunately, was just patient and was, like, ‘Hey, I’m in the pool. I’m hanging out,’” Long said.

A very chill stepmom tactic.

But by the sixth day, things were less chill. If a bond doesn’t form in seven days, then it likely never will, Long said.

Aquarium personnel would get excited every time the pup swam closer to Millie. When the two otters finally united, after nearly seven days, cheers erupted from the office where they watched the events unfold on a livestream.

Millie and 968, seen on a TV screen at the Long Beach aquarium, are now inseparable.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

“I don’t know that that’s going to fade,” Long said of the collective enthusiasm. “There’s some invested people on this project, [and] this has become a very popular corner of our administration.”

Now Millie and the pup are inseparable. In late March, 968 rested on Millie’s belly the best she could — the pup had grown to around 18 pounds, from about 11 when she arrived in Long Beach.

After a relaxing nap in the sun, they made their way to the other side of the pool. The pup, now about 4½ months old, played with a piece of a crab shell as Millie relaxed on a platform. Soon the hyper baby scampered up next to mom in what appeared to be the otter version of “Ma, look at me!” According to Long, the pup was in a stage akin to the terrible twos.

Millie, in a sense, is giving back to the program. She was raised through surrogacy herself and for a while did just fine in the wild — until people started feeding her, which is illegal, experts said.

When she was about 2½ years old, she started jumping on kayaks, and federal wildlife officials ordered her out of the water. When Millie was fished out, it turned out she was pregnant. (Millie’s story is reminiscent of the surfboard-stealing otter that became a national sensation over the summer. That otter, dubbed 841, gave birth in the wild shortly after her antics grabbed headlines.)

Millie raised her pup using the surrogacy program protocols, and it was eventually released. It appears her maternal instinct hasn’t faded.

The sea otter surrogacy program exhibit at the Aquarium of the Pacific in Long Beach doesn’t have a live video feed of Millie and 968, but it does have cute baby otter footage.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

The test

The release of 968 will depend on whether she can reach certain developmental milestones. She has to show she can care for her luxurious fur; crack open clams, mussels and other food; socialize reasonably well with other otters and avoid humans.

She’ll separate from Millie when she’s about 6 months old — the age pups typically leave “home” — and head back to the Monterey aquarium where she’ll hang out with otters closer to her own age. There, she’ll also get the opportunity to hunt live prey.

If all goes well and she passes a final health exam, she’ll return to her native waters. She’ll be implanted with a tracker and rigorously monitored for two weeks. After that period, her survival chances are as good as any otter.

Unfortunately, you can’t wave to 968.

Because the surrogacy program hinges on keeping humans away, visitors at the Long Beach and Monterey aquariums won’t be able to see the otters. The rearing pools at the Aquarium of the Pacific are tucked behind a medical center and a marine mammal protection law prohibits livestreaming their activities to the public.

However, the Long Beach aquarium has launched an exhibit explaining the program. And, yes, it does include adorable video of baby otters.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

Science

A champion of psychedelics who includes a dose of skepticism

Book Review

Trippy: The Peril and Promise of Medicinal Psychedelics

By Ernesto Londoño

Celadon Books: 320 pages, $29.99

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Ernesto Londoño’s engrossing and unsettling new book, “Trippy: The Peril and Promise of Medicinal Psychedelics,” is part memoir, part work of journalism. It tells of how Londoño sought relief from depression with mind-altering drugs. It also investigates the current fad of “medicinal” psychedelics as a treatment for those struggling with depression, trauma, suicidality and other conditions.

Like other psychedelic enthusiasts, Londoño — a journalist who reported in conflict zones such as Iraq and Afghanistan and served as the New York Times’ Brazil bureau chief — wants us to like psychedelics. They relieve him of depression and suicidality. He then continues to “trip” to engage in self-exploration: escape reality, journey into himself and return with an expanded view of the world.

Calling street drugs and hallucinogenics such as psilocybin, MDMA/ecstasy, LSD and ayahuasca “medicine” is problematic. Psychedelic psychiatry has had a resurgence in the past decade, though only among a minority of medical professionals. Mainstream psychiatry largely abandoned psychedelics by the 1970s, for a variety of reasons.

The renewed interest in psychedelics as a treatment seems to arise more from hope than science — a wish that medicinal psychedelics will be effective because our current treatments are inadequate. Antidepressants known as SSRIs and other approaches are often ineffectual, but that doesn’t mean psychedelics, which can be damaging to many in acute distress, should be tried.

Londoño is more balanced in discussing the benefits and dangers than Michael Pollan and others. Pollan’s bestselling book-turned-Netflix-series “How to Change Your Mind” proselytizes medicinal psychedelics in a way that “Trippy” thankfully doesn’t.

Londoño brings a healthy dose of skepticism. Psychedelics aren’t romanticized with examples of the counterculture movement of the 1960s or hyped by listing celebrities currently using them. The author often questions how much of what he’s part of is “a cult” and if what he’s taking is “voodoo,” not medicine.

Ernesto Londoño, author of “Trippy.”

(Jenn Ackerman)

“Trippy” is a fascinating account of the world of medicinal psychedelics. We attend psychedelic retreats in the Amazon and Latin America. We drink ayahuasca, a syrupy, foul-tasting psychoactive tea that induces vomiting and hallucinations. Ayahuasca calls back “memories” — some real, others false — that participants take as the cause of their emotional ill health.

We visit a ketamine clinic, where Londoño feels a “blissful withdrawal,” retaining “strong powers of perception” but losing “any sense of being a body with limbs that can move at will.”

We watch MDMA (a German pharmaceutical from 1912 now best known as the street drug called ecstasy or molly) being administered at a veterans hospital to treat post-traumatic stress disorder. At a “treatment center”/church/spiritual refuge in Austin, Texas, we witness tobacco being blown into a man’s nostrils, extract from an Amazonian plant squirted into his eyes, and toad venom burned into his forearms under the guise of spiritual salvation.

Unlike the unbridled enthusiasts, Londoño exposes the predatory nature of the psychedelic industry and how it exoticizes the use of hallucinogens as Indigenous medicines. We’re privy to some scandals in this field, specifically sexual abuse and harassment and taking advantage of vulnerable people looking for help.

It’s an engaging memoir of one man’s experiences with psychedelics. Londoño’s little asides, like when he’s talking about meeting the man who would become his husband, endear him to us: “I saw the profile of a handsome man visiting from Minnesota for the weekend. He was a vegetarian and veterinarian. Swoon!”

But as a work of mental health journalism, “Trippy” isn’t, as the book jacket suggests, “the definitive book on psychedelics and mental health today.”

Much is overlooked and left out. Londoño fails to stress that these treatments best serve the “worried well,” those struggling with relatively mild complaints, but can be extremely unsafe for those with serious mental illness, meaning severe dysfunction. Such a person has typically been diagnosed with bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder with suicidality, post-traumatic stress or schizophrenia. They can’t hold a job or live independently, often for years.

Most people Londoño interviews in “Trippy” seek “bliss,” not lifesaving measures to give them a chance at basic functioning. The retreats are less mental health centers than gatherings of spiritual seekers.

Full disclosure: I read “Trippy” with an open mind and as someone who spent 25 years in the American mental health system with serious mental illness. Those years passed the way they do for so many: a string of hospitalizations endured, countless therapeutic modalities tried, numerous mental health professionals seen and myriad psychiatric medications taken (yes, in the double digits).

“Medicinal” psychedelics never came up as a potential treatment. I recovered before fringe psychiatry’s renewed interest in psychedelics became a fad in the past decade.

It’s unsettling that Londoño doesn’t mention the recovery movement and what we know can lead to mental health recovery. He doesn’t mention the five Ps, which are based on the four Ps that Thomas Insel, former head of the National Institute of Mental Health, writes about in “Healing: Our Path from Mental Illness to Mental Health.” To heal, we need people (social support), place (a safe home), purpose (meaning in life), payment (access to mental health care) and physical health (a clean diet and, ironically, no drugs or alcohol).

In this, Londoño fails to explore whether his recovery had as much to do with the changes he made as a result of his first treatment/trip as with psychedelics themselves: changes in diet, renewed purpose, finding love, moving into a new home, leaving his stressful job. If two centuries of psychiatric research has taught us one thing, it’s that there is no magic bullet for mental health recovery.

The book’s most compelling explorations into psychedelics as mental health treatments come when Londoño discusses their use in treating trauma, particularly that which war journalists and veterans experience.

He also explores the pervasiveness of mental health issues and the particular challenges LGBTQ+ people can face.

“Trippy” raises seminal questions we need to be asking as the psychedelic industry reaches further into mental health treatment:

What is “medicine” and what is an illicit drug?

Are we trying to treat those in crisis or simply help anyone escape the suffering that’s part of the human experience?

Should we continue to try more and more extreme treatments?

Or should we finally pay attention to and change systemic issues that are the root cause of so much mental and emotional distress?

Sarah Fay is the author of the bestselling memoirs “Pathological: The True Story of Six Misdiagnoses” and “Cured.”

Science

Maps of Two Cicada Broods, Reunited After 221 Years

This spring, two broods of cicadas will emerge in the Midwest and the Southeast, in their first dual appearance since 1803.

A cicada lays eggs in an apple twig.

“Insects: Their Ways and Means of Living,” by Robert E. Snodgrass, 1930, via the Biodiversity Heritage Library

Brood XIII, the Northern Illinois Brood, hatched and burrowed into the ground 17 years ago, in 2007.

Brood XIX, the Great Southern Brood, hatched in 2011 and has spent 13 years underground, sipping sap from tree roots.

The entomologist Charles L. Marlatt published a detailed map of Brood XIX, the largest of the 13-year cicada broods, in 1907.

Historic map of cicada emergence.

He also mapped the expected emergence of Brood XIII in 1922.

Historic map of cicada emergence.

This spring the two broods will surface together, and are expected to cover a similar range.

Modern map of cicada emergence.

Up to a trillion cicadas will rise from the warming ground to molt, sing, mate, lay eggs and die.

A Name and a Number

Charles L. Marlatt proposed using Roman numerals to identify the regional groups of 13- and 17-year periodical cicadas, beginning with Brood I in 1893.

A brood can include up to three or four cicada species, all emerging at the same time and singing different songs. Long cicada lifespans of 13 or 17 years spent underground have spawned many theories, and may have evolved to reduce the likelihood of different broods surfacing at the same time.

Large broods might sprawl across a dozen or more states, while a small brood might only span a few counties. Brood VII is the smallest, limited to a small part of New York State and at risk of disappearing.

At least two named broods are thought to have vanished: Brood XXI was last seen in 1870, and Brood XI in 1954.

Not Since the Louisiana Purchase

Brood XIII and Brood XIX will emerge together this year, for the first time in more than two centuries. But only in small patches of Illinois are they likely to come out of the ground in the same place.

In 1786 and 1790, the two broods burrowed into Native lands, divided by the Mississippi River into nominally Spanish territory and the new nation of the United States.

An historic map of the United States from 1783.

Brood XIII entered the ground in 1786, and Brood XIX in 1790. (Expected 2024 ranges are overlaid on the map.)

An historic map of the United States from 1783.

As the ground was warming in April 1803, France sold the rights to the territory of Louisiana, which it acquired from Spain in 1800, to the United States for $15 million.

An historic map of the United States from 1801. That spring, Brood XIII and Brood XIX emerged together into a newly enlarged United States.

An historic map of the United States from 1803.

Their descendants — 13 and 17 generations later — are now poised to return, and will not sing together again until 2245. An historic map of the United States from 1868.

A ‘Great Visitation’

After an emergence of Brood X cicadas in 1919, the naturalist Harry A. Allard wrote:

Although the incessant concerts of the periodical cicadas persisting from morning until night became almost disquieting at times, I felt a positive sadness when I realized that the great visitation was over, and there was silence in the world again, and all were dead that had so recently lived and filled the world with noise and movement.

It was almost a painful silence, and I could not but feel that I had lived to witness one of the great events of existence, comparable to the occurrence of a notable eclipse or the invasion of a great comet.

Then again the event marked a definite period in my life, and I could not but wonder how changed would be my surroundings, my experiences, my attitude toward life, should I live to see them occur again seventeen years later.

The transformation of a cicada nymph (1), into an adult (10).

“The Periodical Cicada,” by Charles L. Marlatt, 1907, via the Biodiversity Heritage Library

Science

What are the blue blobs washing up on SoCal beaches? Welcome to Velella velella Valhalla

The corpses are washing up by the thousands on Southern California’s beaches: a transparent ringed oval like a giant thumbprint 2 to 3 inches long, with a sail-like fin running diagonally down the length of the body.

Those only recently stranded from the sea still have their rich, cobalt-blue color, a pigment that provides both camouflage and protection from the sun’s UV rays during their life on the open ocean.

Aggressive and impactful reporting on climate change, the environment, health and science.

These intriguing creatures are Velella velella, known also as by-the-wind sailors or, in marine biology circles, “the zooplankton so nice they named it twice,” said Anya Stajner, a biological oceanography PhD student at UC San Diego’s Scripps Institution of Oceanography.

A jellyfish relative that spends the vast majority of its life on the surface of the open sea, velella move at the mercy of the wind, drifting over the ocean with no means of locomotion other than the sails atop their bodies. They tend to wash up on the U.S. West Coast in the spring, when wind conditions beach them onshore.

Springtime velella sightings documented on community science platforms like iNaturalist spiked both this year and last, though scientists say it’s too early to know if this indicates a rise in the animal’s actual numbers.

Velella are an elusive species whose vast habitat and unusual life cycle make them difficult to study. Though they were documented for the first time in 1758, we still don’t know exactly what their range is or how long they live.

These beaching events confront us with a little-understood but essential facet of marine ecology — and may become more common as the oceans warm.

“Zooplankton” — the tiny creatures at the base of the marine food chain — “are sort of this invisible group of animals in the ocean,” Stajner said. “Nobody really knows anything about them. No one really cares about them. But then during these mass Velella velella strandings, all of a sudden there’s this link to this hidden part of the ocean that most of us don’t get to experience.”

What looks like an individual Velella velella is actually a colony of teeny multicellular animals, or zooids, each with their own function, that come together to make a single organism. They’re carnivorous creatures that use stinging tentacles hanging below the surface to catch prey such as copepods, fish eggs, larval fish and smaller plankton.

Unlike their fellow hydrozoa, the Portuguese man o’ war, the toxin in their tentacles isn’t strong enough to injure humans. Nevertheless, “I wouldn’t encourage anyone to touch their mouth or their eyes after they pick one up on the beach,” said Nate Jaros, senior director of fishes and invertebrates at the Aquarium of the Pacific in Long Beach.

Velella that end their lives on California beaches typically have sails that run diagonally from left to right along the length of their bodies, an orientation that catches the onshore winds heading in this direction. As the organism’s carcass dries in the sun and the soft tissues decay, the blue color disappears, leaving the transparent chitinous float behind.

“The wind really just brings them to our doorstep in the right conditions,” Jaros said. “But they’re designed as open ocean animals. They’re not designed to interact with the shoreline, which is usually why they meet their demise when they come into contact with the shore.”

1

2

3

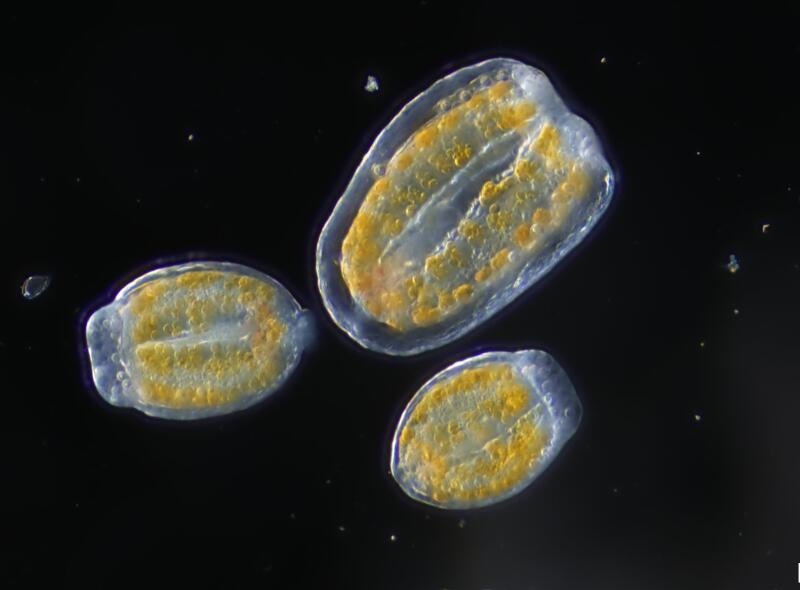

1. Anya Stajner put Velella velella under a microscope. 2. Magnified, you can see more than blue in the organism. “That green and brown coloration comes from their algae symbionts,” Stajner said. 3. Notice the tentacles too. (Anya Stajner)

Velella show up en masse when two key factors coincide, Stajner said: an upwelling of food-rich, colder water from deeper in the ocean, followed by shoreward winds and currents that direct the colonies to beaches.

A 2021 paper from researchers at the University of Washington found a third variable that appears to correlate with more velella sightings: unusually high sea surface temperatures.

After looking at data over a 20-year period, the researchers found that warmer-than-average winter sea surface temperatures followed by onshore winds tended to correlate with higher numbers of velella strandings the following spring, from Washington to Northern California.

“The spring transition toward slightly more onshore winds happens every year, but the warmer winter conditions are episodic,” said co-author Julia K. Parrish, a University of Washington biologist who runs the Coastal Observation and Seabird Survey Team community science project.

Given that sea surface temperatures have been consistently above the historical average every day since March 2023, the current velella bloom is consistent with those findings.

Previous research has found that gelatinous zooplankton like velella and their fellow jellyfish thrive in warmer waters, portending an era some scientists have referred to as the “rise of slime.”

Other winners of a slimy new epoch would be ocean sunfish, a giant bony fish whose individuals can clock in at more than 2,000 pounds and consume jellyfish — and velella — in mass quantities. Ocean sunfish sightings tend to rise when velella observations do, Jaros said.

“The ocean sunfish will actually kind of put their heads out of the water as they eat these. It resembles Pac-Man eating pellets,” he said. (KTLA-TV published a picture of just that this week.)

Though velella blooms are ephemeral, we don’t yet know how long any individual colony lives. The blue seafaring colonies are themselves asexual, though they bud off tiny transparent medusas that are thought to go to the deep sea and reproduce sexually there, Stajner said. The fertilized egg then evolves into a float that returns to the surface and forms another colony.

Anya Stajner, a PhD student at Scripps, collected by-the-wind sailors but was unable to keep them alive in a lab. “Rearing gelatinous organisms is pretty difficult,” she said.

“I was able to actually collect some of those medusae last year during the bloom, but rearing gelatinous organisms is pretty difficult,” Stajner said. The organisms died in the lab.

Stajner left May 1 on an eight-day expedition to sample velella at multiple points along the Santa Lucia Bank and Escarpment in the Channel Islands, with the goal of getting “a better idea of their role in the local ecosystem and trying to understand what these big blooms mean,” she said.

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoBoth sides prepare as Florida's six-week abortion ban is set to take effect Wednesday

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoColumbia University’s policy-making senate votes for resolution calling to investigate school’s leadership

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoGOP Rep. Bill Posey won't seek re-election, endorses former Florida Senate President as replacement

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoBrussels, my love? MEPs check out of Strasbourg after 5 eventful years

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoRussian forces gained partial control of Donetsk's Ocheretyne town

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoHouse Republicans brace for spring legislative sprint with one less GOP vote

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoAt least four dead in US after dozens of tornadoes rip through Oklahoma

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoAnti-Trump DA's no-show at debate leaves challenger facing off against empty podium