Science

Sex, radiation and mummies: How farms are fighting a pesky almond moth without pesticides

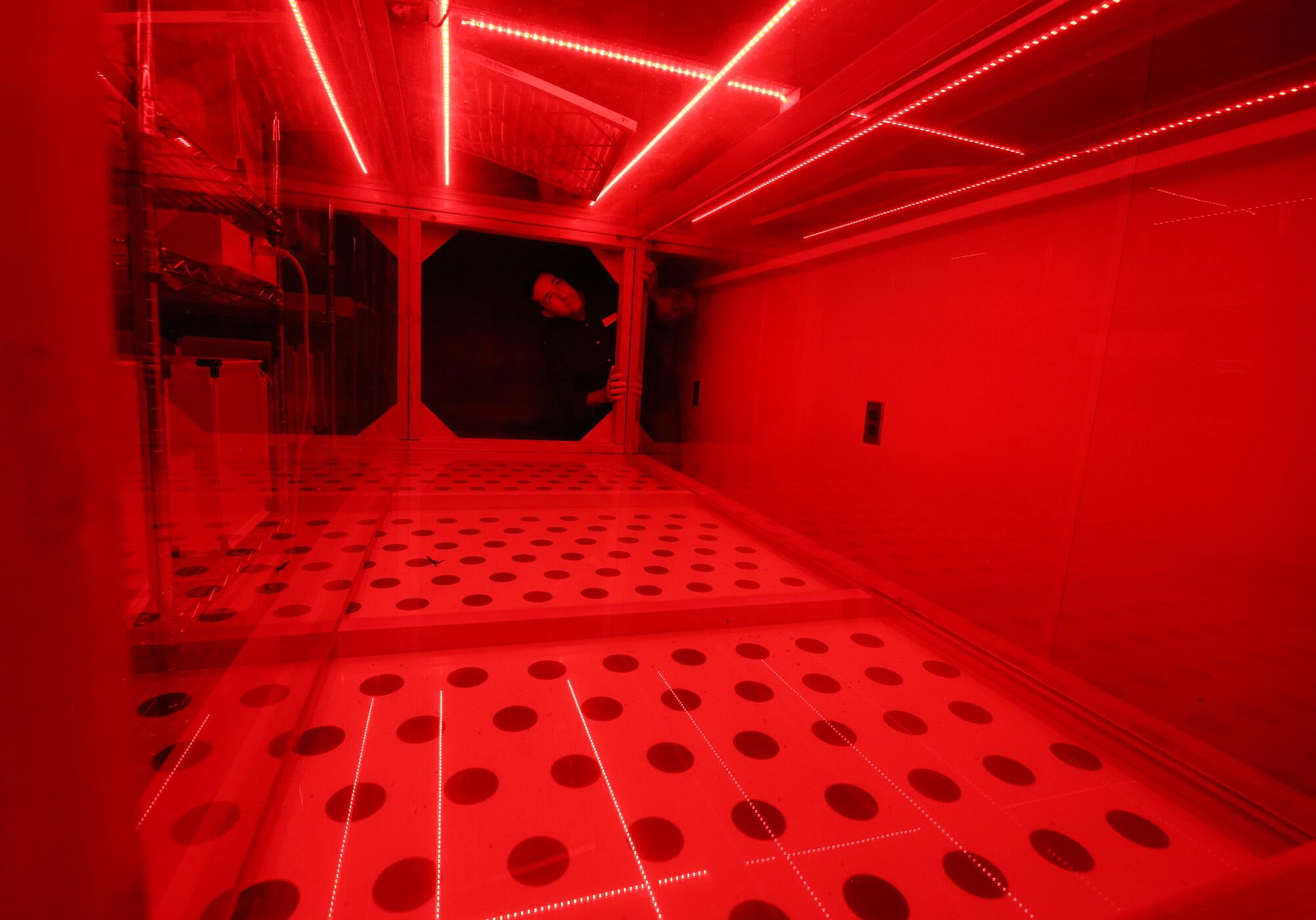

In a windowless shack on the far outskirts of Fresno, an ominious red glow illuminates a lab filled with X-ray machines, shelves of glowing boxes, a quietly humming incubator and a miniature wind tunnel.

While the scene looks like something straight out of a sci-fi movie, its actually part of an experimental program to prevent a damaging almond pest from successfully mating.

A moth trap hangs from the branch of an almond tree.

(Gary Kazanjian / For The Times)

With California almond growers reeling from dropping nut prices and rising costs, the pests have only added to their woes.

Every year, the navel orangeworm eats through roughly 2% of California’s almonds before they can make it to grocery store shelves. Last year, it was almost double that.

While that might seem small, if you do the math “it’s going to be a lot of millions of dollars lost to this pest,” said David Haviland, a Kern County farm advisor with University of California Agriculture and Natural Resources. “And that’s despite the control methods that people use,” he said.

California produces 80% of the world’s almonds, yet in 2022 the production value of the nut fell 34% compared with the previous year.

Scientists say climate change could make the navel orangeworm problem even worse, with hotter temperatures allowing the moths to reproduce even faster. (Despite its name, the insect has largely left citrus farms unbothered and is in fact a moth.)

Traditionally, nut farmers have tackled the insect with chemical pesticides, or by destroying “mummies” — almonds left over after harvest. Mummies are a favorite winter shelter for the bugs.

However, research is increasingly showing that chemical pesticides are not only harmful to the environment but to people as well. One new study found that the impact of nearby pesticide use on cancer incidence “may rival that of smoking.”

“When you have to don a spacesuit, basically, to apply something, you’re definitely thinking, ‘This is not good,’” said Houston Wilson, an entomologist with UC ANR’s Kearney Agricultural Research and Extension Center and the mastermind behind the sci-fi shack.

“Across the board, folks want to get away from chemical controls,” he said.

So farmers and researchers have been searching for other non-pesticide alternatives.

Removing almost every last mummy from every tree in an orchard can be effective, but since it must be done manually, it can become too expensive and complex for some growers.

Another tactic that’s been used since around 2010 is to cover orchards with disorienting levels of sex pheromones to confuse horny moths — a technique known as “mating disruption.”

But with limited budgets and climate change threatening to make the pest situation worse, researchers are studying another yet-to-be-proven approach: sterilizing almost a million moths a day with radiation and dropping them out of planes.

Houston Wilson looks over trapped moths at the Kearney Agricultural Research and Extension Center in Parlier, Calif.

(Gary Kazanjian / For The Times)

The idea behind the technique is that by flooding orchards with sterilized insects, they will mate with fertile insects and produce no offspring, reducing the overall population.

The simplest way to sterilize the bugs is to use radiation. Since their reproductive genes tend to mutate faster, the right dose can leave them relatively unfazed but unable to reproduce.

At the request of almond and pistachio farmers, the California Department of Food and Agriculture has been working with the Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service of the U.S. Department of Agriculture since 2018 to source sterilized moths from a Phoenix lab.

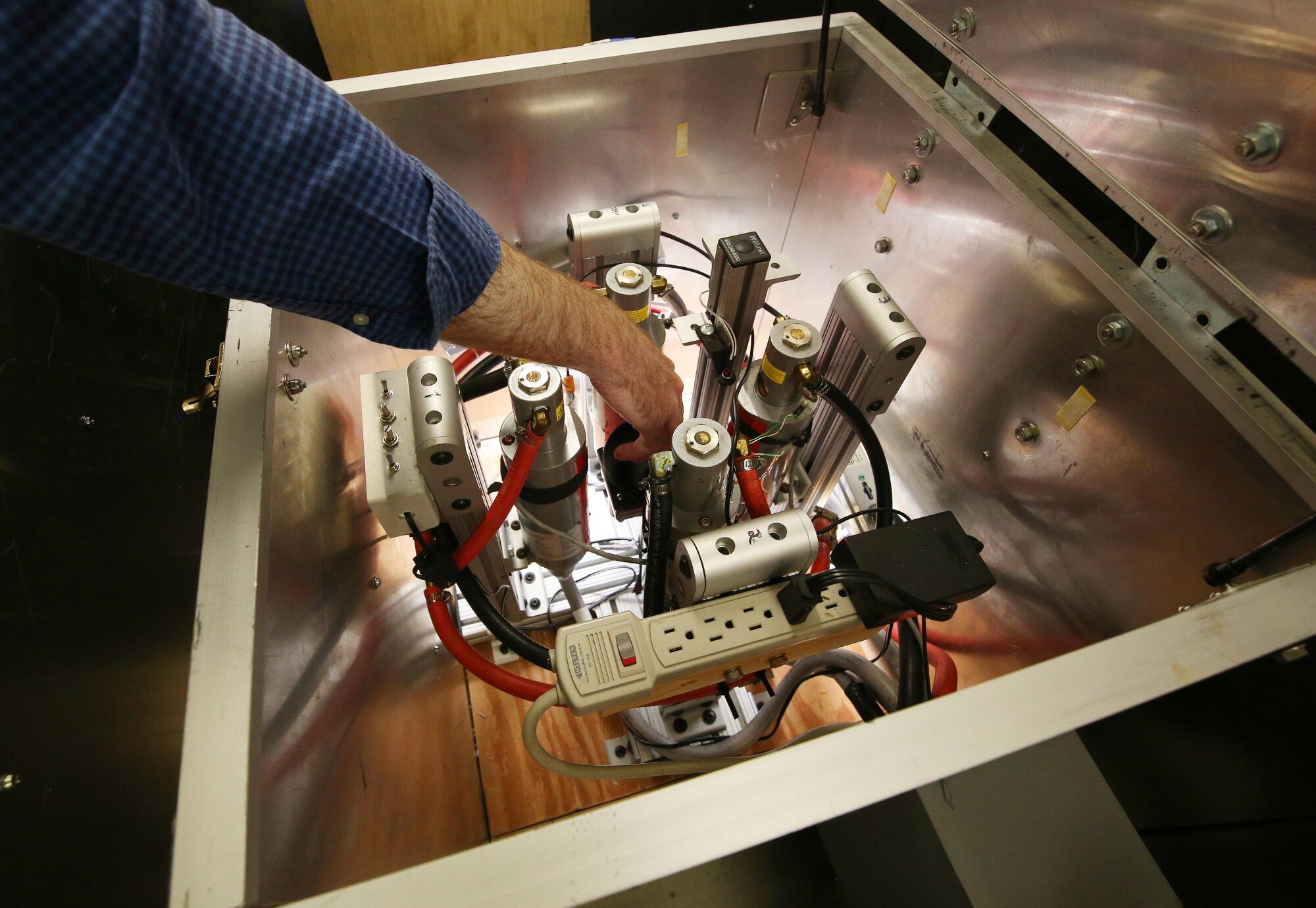

An X-ray machine designed to sterilize moths is shown at the Kearney Agricultural Research and Extension Center.

(Gary Kazanjian / For The Times)

The lab sterilizes about 750,000 bugs per day, then chills the moths to put them to sleep and ships them off to California. The bugs are dropped from an airplane hundreds of feet in the air. Often too sleepy to fly, the insects crash into the hard ground or almond trees.

From there, the survivors have only one job: have sex.

Through this test program, the USDA hopes to perfect the best ways to get moths to reproduce in the lab and give them the right dose of radiation that will sterilize them but not severely injure or disorient them.

The program has yet to put a significant dent in the moth population, though, because they can’t produce enough sterile bugs.

Right now, researchers are only finding a couple of sterile insects in traps for every hundred wild fertile moths. For the technique to be effective, they’ll need to deploy dozens of sterile bugs for every wild one.

Anisa Bel Guzman counts moths at the Kearney Agricultural Research and Extension Center in Parlier, Calif.

(Gary Kazanjian / For The Times)

Matthew Aubuchon, national policy manager at the USDA’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, estimated that the Phoenix facility could produce up to 8 million moths per day with enough staff working around the clock.

While opening more facilities in California would help, the program uses cobalt to produce high-energy radiation to sterilize the bugs — which is expensive and requires the lab to take extensive safety and security measures.

Wilson’s sci-fi shack at Kearney might hold a solution that is cheaper and easier to scale.

Instead of using cobalt or other radioactive materials, Wilson’s team uses an X-ray machine to irradiate the pests. (Unlike a radioactive substance, an X-ray machine will not emit radiation when it is turned off.)

Then, the team puts their X-rayed bugs and the sterilized insects from Phoenix through a series of tests to determine which methods produce the healthiest, sterile moths.

The tests include gluing moths to the end of a stick suspended in the air. The stick rotates like a carousel as the moths flutter around and researchers record how well they can fly.

Houston Wilson looks into an insect wind tunnel as researchers look for innovative ways to manage an invasive almond pest.

(Gary Kazanjian / For The Times)

The researchers also place moths in a wind tunnel and release sex pheromones to see if the excited bugs are able to locate the smell. (Unfortunately for the insects, there are no potential mates at the end of the tunnel.)

While the team doesn’t yet produce enough X-rayed moths to test them in a full-blown almond orchard, they do send the Phoenix moths into their final test: releasing them into their seven-acre almond farm on the Kearney campus to see how good they are at actually finding fertile moths to mate with.

Houston Wilson looks over a navel orangeworm trap in an almond field in Parlier.

(Gary Kazanjian / For The Times)

The researchers at Kearney may be in a race against time, however.

Scientists say it’s possible that climate change will continue to tip the weather in the moths’ favor. The metabolism of navel orangeworms — like many agricultural pests — is tied to temperature. The hotter it is, the faster they grow and reproduce.

A 2021 study found that the moths, which can have life cycles as short as just one month, may be able to squeeze in another generation each summer before holing up in nuts for the winter.

“For each additional generation, their population is increasing at an exponential rate,” said Tapan Pathak, an author on the study and a professor at UC Merced.

“If this additional generation is coinciding with … harvest,” Pathak said, “then they become unmarketable. That’s a huge economic loss.”

However, the food web is complicated, and just because the warmer weather benefits the moths on paper doesn’t mean the moths will end up on top.

Every year, navel orangeworms eat through roughly 2% of California’s almonds before they can make it to grocery store shelves.

(Gary Kazanjian / For The Times)

“Navel orangeworm could be a nightmare … but it could also become less of a problem because all the things that eat it benefit more from the heat than the navel orangeworm,” said Haviland. “The crystal ball is certainly not clear enough to know what will happen.”

Researchers stress that successful pest control will require multiple measures.

“What we’ve learned through integrated pest management is that the timing of one or staggering of different approaches together yields results for the growers,” said Aubuchon.

The tried-and-true non-pesticide method growers have been using since the moths’ unannounced arrival in the 1940s is to simply ensure all the almonds are either harvested or destroyed by the time winter arrives.

But for this method to be effective, there must be no more than two almonds left on every tree in an orchard. This can be hard to achieve in wet weather.

Rain makes almond branches soggy and flexible, which makes it hard to snap nuts off using an industrial shaker. Damp earth can also make it difficult for machines to get close to the trees.

Instead, workers must use poles to knock almonds off manually. As effective as this is, increasing labor costs mean some farms just can’t afford it.

Anisa Bel Guzman counts moths at the Kearney Agricultural Research and Extension Center in Parlier.

(Gary Kazanjian / For The Times)

While researchers say the sterile insect technique still has a lot of hurdles to clear before it will be widely effective, they say it holds great promise.

“You’re literally managing a pest by preventing it from being born in the first place,” said Haviland of both sterile insect technique and pheromone mating disruption. “To think that something like that was possible 10 or 15 years ago — nobody could imagine that growers would be using such innovative techniques as those.”

Science

A retired teacher found some seahorses off Long Beach. Then he built a secret world for them

Rog Hanson emerges from the coastal waters, pulls a diving regulator out of his mouth and pushes a scuba mask down around his neck.

“Did you see her?” he says. “Did you see Bathsheba?”

On this quiet Wednesday morning, a paddle boarder glides silently through the surf off Long Beach. Two stick-legged whimbrels plunge their long curved beaks into the sand, hunting for crabs.

Classic stories from the Los Angeles Times’ 143-year archive

But Hanson, 68, is enchanted by what lies hidden beneath the water. Today he took a visitor on a tour of the secret world he built from palm fronds and pine branches at the bottom of the bay: his very own seahorse city.

The visitor confirms that she did see Bathsheba, an 11-inch-long orange Pacific seahorse, and a grin spreads across Hanson’s broad face.

“Isn’t she beautiful?” he says. “She’s our supermodel.”

If you get Hanson talking about his seahorses, he’ll tell you exactly how many times he’s seen them (997), who is dating whom, and describe their personalities with intimate familiarity. Bathsheba is stoic, Daphne a runner. Deep Blue is chill.

He will also tell you that getting to know these strange, almost mythical beings has profoundly affected his life.

“I swear, it has made me a better human being,” he says. “On land I’m very C-minus, but underwater, I’m Mensa.”

Hanson is a retired schoolteacher, not a scientist, but experts say he probably has spent more time with Pacific seahorses, also known as Hippocampus ingens, than anyone on Earth.

“To my knowledge, he is the only person tracking ingens directly,” says Amanda Vincent, a professor at the University of British Columbia and director of the marine conservation group Project Seahorse. “Many people love seahorses, but Roger’s absorption with them is definitely distinctive. There’s a degree of warm obsession there, perhaps.”

Rog Hanson keeps watch over a small colony of Pacific seahorses.

(Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times)

Over the last three years, Hanson has made the two-hour trek from his home in Moreno Valley to the industrial shoreline of Long Beach to visit his “kids” about every five days. To avoid traffic, he often leaves at 2 a.m. and then sleeps in his car when he arrives.

He keeps three tanks of air and his scuba gear in the trunk of his 2009 Kia Rio. A toothbrush and a pair of pink leopard print reading glasses rest on the dash.

Hanson makes careful notes after all his dives in a colorful handmade log book he stores in a three-ring binder. On this Wednesday he dutifully records the water temperature (62 degrees), the length of the dive (58 minutes), the greatest depth (15 feet) and visibility (3 feet), as well as the precise location of each seahorse. His notes also include phase of the moon, the tidal currents and the strength of the UV rays.

“Scientists will tell you that sunlight is an important statistic to keep down,” he says.

He has given each of his four seahorses a unique logo that he draws with markers in his log book. Bathsheba’s is a purple star outlined in red, Daphne’s is a brown striped star in a yellow circle.

Rog Hanson makes careful notes after all his dives. He has given each of his four seahorses a unique logo.

(Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times)

He’s learned that the seahorses don’t like it when he hovers nearby for too long. Now he limits his interactions with them to 15 to 30 seconds at a time.

“At first I bugged them too much,” he says. “I was the paparazzi swimming around.”

Hanson traces the origins of his seahorse story back nearly two decades to the early morning of Dec. 30, 2000.

He was diving solo off Shaw’s Cove in Laguna Beach when a slow-moving giant emerged from the abyss. It was a gray whale whose 40-foot frame cast Hanson in shadow.

The whale could have killed him with a flick of its tail, Hanson says, but he felt no fear. The two made eye contact and, as Hanson tells it, he felt the whale’s gaze peering directly into his soul.

It was all over in 10 seconds, but Hanson was altered. He had always wanted to live at the beach, but after this encounter, he vowed to make it happen. It took years —15, in fact — but he finally got a job as a special education teacher in the Long Beach public school system. He bought a van and parked it on Ocean Boulevard. He lived at the beach and dived every day for 3½ months before moving to Moreno Valley.

To amuse himself while he lived at the beach, he built an underwater city he called Littleville out of discarded toys he found at the bottom of the bay.

Hanson saw his first seahorse in January 2016 while checking on Littleville. It was bright orange, just 4.5 inches long, and Hanson, who had logged over a thousand dives in the area, knew it didn’t belong there.

Daphne is one of the seahorses that Rog Hanson is studying in Alamitos Bay.

(Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times)

The range of the Pacific seahorse is generally thought to extend from Peru to as far north as San Diego. This seahorse ended up about 100 miles north of that.

Scientists said the seahorse and others that joined her had probably ridden an unusual pulse of warm water up the coast, along with other animals generally found in southern waters.

“We were getting a lot of weird sightings in the fall of 2015,” says Sandy Trautwein, vice president of husbandry at the Aquarium of the Pacific. “There was a yellow-bellied sea snake, bluefin tuna, marlin, whale sharks — a lot of animals associated with warm water.”

Most of these animals eventually left after ocean temperatures returned to normal, but Hanson’s seahorses stayed.

That may be because Hanson had built them a home.

It happened like this: In June 2016 he watched in horror as more than 100 high school football players splashed in the shallow waters, right where his seahorses usually hung out.

“I thought, I gotta do something, I gotta do something,” he says.

“On land I’m very C-minus, but underwater, I’m Mensa.”

— Rog Hanson

Then he remembered that, back in the Midwest where he grew up, he used to help the city park service make “fish cribs.” In early spring they would use brush and twigs to build what looked like a miniature log cabin with no roof on an ice-covered lake. When the ice melted, the cribs would fall to the bottom, creating a habitat for fish and other animals.

“So I said to myself, build them a city that’s deeper, where feet can’t get to it even at low tide,” Hanson says.

And he did.

By July 2016 two pairs of seahorses had moved into the new habitat. Daphne, the runner, was named after the nymph from Greek mythology who flees Apollo, Kenny’s name came from the proprietor of a local kayaking company. “Bathsheba” was inspired by a Bible story, and her mate, Deep Blue, named after a dive shop that has helped sponsor Hanson’s work since he launched his seahorse study.

He’s seen Kenny’s and Deep Blue’s bellies swell with pregnancy and noted how their partners check in on them daily, frequently standing sentinel nearby. He’s visited the fish at odd hours to see how their behavior changes from morning to night. And he mourned when Kenny disappeared in January. He still hasn’t come back. (A new member, CD Street, arrived June 29.)

“It feels like I’m reading a book, the book of their life, and I can’t put it down,” he says.

He’s also reached out to seahorse scientists across the globe to compare notes. “I won’t say I know the most about seahorses in the world, but I know the people who do,” he says.

Amanda Vincent, the director of Project Seahorse, says that seahorses spark an emotional reaction in almost everyone.

Daphne is one of the seahorses that Rog Hanson is studying in Alamitos Bay. Hanson and Ashley Arnold keep watch over a small colony of Pacific seahorses.

(Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times)

“Remember those books with three flaps where you can mix the head of a giraffe with the body of a snake and the tail of a monkey? That’s what we’ve got here,” she says. “They appeal to the sense of fancy and wonder in us.”

When Mark Showalter, a planetary astronomer at the SETI Institute, recently discovered a moon orbiting Neptune, he named it Hippocamp in part because of his love of seahorses.

“I’ve seen them in the wild and they are marvelously strange and interesting,” he says. “It’s a fish, but it doesn’t look anything like a fish.”

Pacific seahorses are among the largest members of the seahorse family. Males can grow up to 14 inches long, while females generally top out at about 11. They come in a variety of colors, including orange, maroon, brown and yellow. They are talented camouflagers that can alter the color of their exoskeleton to blend into their environment.

“I won’t say I know the most about seahorses in the world, but I know the people who do.”

But perhaps their most distinguishing characteristic is that they are the only known species in the animal kingdom to exhibit a true male pregnancy. Females deposit up to 1,500 eggs in the male’s pouch. The males incubate the eggs, providing nutrition and oxygen for the growing embryos. When the larval seahorses are ready to be released, he goes into labor — scientists call it “jackknifing” — pushing his trunk toward his tail.

After three years of observation, Hanson has collected new evidence about seahorse mating practices. His research suggests that although most seahorses are monogamous, a female will mate with two males if there are no other female seahorses around.

He also found that males, who are in an almost constant state of pregnancy, tend to stick to an area about the size of a king-size mattress, while the females roam up to 150 feet from their home during a typical day.

Eventually, he may be able to help scientists answer another long-standing question: What is the lifespan of Pacific seahorses in the wild? Some researchers say about five years; others think it could be up to 12.

“It will be interesting to see what Roger finds out,” Vincent says.

In June 2017, about one year after Hanson began formally tracking the seahorses, he took on a partner: a young scuba instructor named Ashley Arnold.

Arnold, who has short red hair and a jocular vibe, is a former Army staff sergeant who served in Iraq and Afghanistan. She learned to dive as part of a program the Salt Lake City Veterans Affairs hospital offered to female veterans suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder and military sexual trauma. Arnold suffered from both. Diving became her salvation.

Dive instructor Ashley Arnold is a former Army staff sergeant who says that diving at least twice a week helps her deal with PTSD and MST.

(Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times)

“All the irritation on the surface disappears when you go under the water,” she says. “It’s like, ‘What was I concerned about?’ You forget about everything else. Nothing else matters.”

She used her GI Bill to pay for a scuba instructor course and to set up her own business. Now, she finds that if she dives at least twice a week and has a dog, she does not need to take medication.

“All the irritation on the surface disappears when you go under the water.”

— Ashley Arnold

“That’s a pretty big statement in my opinion,” she says.

Arnold and Hanson met in June 2016 on a dive trip to Catalina. Hanson mentioned his seahorses. Arnold was intrigued, but still lived in Salt Lake City.

One year later, Arnold moved to Huntington Beach and gave Hanson a call.

“I said, ‘Hey Roger, let’s chat. Any chance I could join you at the seahorses you talked about?’” she says. “And he decided I was acceptable.”

Now, Arnold and her boyfriend, Jake Fitzgerald, check in on the seahorses about once a week and help Roger rebuild the city he created for them.

Rog Hanson, 68, teamed up with dive instructor Ashley Arnold two years ago to keep watch over a small colony of Pacific seahorses.

(Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times)

“We call them our kids because we love them so much,” Arnold says.

Hanson and Arnold are very protective of their seahorse family. They tell visitors to remove GPS tags from their photos. They swear them to secrecy.

There is little chance anyone would find Hanson’s seahorses without a guide. Also, diving in these waters off Long Beach can be a challenge.

The water is shallow. It’s hard to get your buoyancy right. A misplaced flipper kick can stir up blinding sand and silt.

But if Hanson wants to show you his underwater world, nothing will stop him. He will hold you firmly by the hand and guide you down to the forest he built at the bottom of the bay.

Ashley Arnold, right, gets rinsed off with a hose by Rog Hanson after a dive Alamitos Bay.

(Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times)

He will use a plastic tent stake, jabbing it into the bottom to propel himself — and you holding on — across the ocean floor. When he spots a seahorse he will use the stake as a pointer. Through the murky water you strain to see. Then it appears.

Orange and rigid. Thin snout. Bony plates. Stripes down the torso. Totally still.

And if you’ve never seen a seahorse in the wild before, you will feel honored and awed, as if you’ve just seen a unicorn beneath the sea.

Science

California’s summer COVID wave shows signs of waning. What are the numbers in your community?

There are some encouraging signs that California’s summer COVID wave might be leveling off.

That’s not to say the seasonal spike is in the rearview mirror just yet, however. Coronavirus levels in California’s wastewater remain “very high,” according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, as they are in much of the country.

But while some COVID indicators are rising in the Golden State, others are starting to fall — a hint that the summer wave may soon start to decline.

Statewide, the rate at which coronavirus lab tests are coming back positive was 11.72% for the week that ended Sept. 6, the highest so far this season, and up from 10.8% the prior week. Still, viral levels in wastewater are significantly lower than during last summer’s peak.

The latest COVID hospital admission rate was 3.9 hospitalizations for every 100,000 residents. That’s a slight decline from 4.14 the prior week. Overall, COVID hospitalizations remain low statewide, particularly compared with earlier surges.

The number of newly admitted COVID hospital patients has declined slightly in Los Angeles County and Santa Clara County, but ticked up slightly up in Orange County. In San Francisco, some doctors believe the summer COVID wave is cresting.

“There are a few more people in the hospitals, but I think it’s less than last summer,” said Dr. Peter Chin-Hong, a UC San Francisco infectious diseases expert. “I feel like we are at a plateau.”

Those who are being hospitalized tend to be older people who didn’t get immunized against COVID within the last year, Chin-Hong said, and some have a secondary infection known as superimposed bacterial pneumonia.

Los Angeles County

In L.A. County, there are hints that COVID activity is either peaking or starting to decline. Viral levels in local wastewater are still rising, but the test positivity rate is declining.

For the week that ended Sept. 6, 12.2% of wastewater samples tested for COVID in the county were positive, down from 15.9% the prior week.

“Many indicators of COVID-19 activity in L.A. County declined in this week’s data,” the L.A. County Department of Public Health told The Times on Friday. “While it’s too early to know if we have passed the summer peak of COVID-19 activity this season, this suggests community transmission is slowing.”

Orange County

In Orange County, “we appear to be in the middle of a wave right now,” said Dr. Christopher Zimmerman, deputy medical director of the county’s Communicable Disease Control Division.

The test positivity rate has plateaued in recent weeks — it was 15.3% for the week that ended Sept. 6, up from 12.9% the prior week, but down from 17.9% the week before that.

COVID is still prompting people to seek urgent medical care, however. Countywide, 2.9% of emergency room visits were for COVID-like illness for the week that ended Sept. 6, the highest level this year, and up from 2.6% for the week that ended Aug. 30.

San Diego County

For the week that ended Sept. 6, 14.1% of coronavirus lab tests in San Diego County were positive for infection. That’s down from 15.5% the prior week, and 16.1% for the week that ended Aug. 23.

Ventura County

COVID is also still sending people to the emergency room in Ventura County. Countywide, 1.73% of ER patients for the week that ended Sept. 12 were there to seek treatment for COVID, up from 1.46% the prior week.

San Francisco

In San Francisco, the test positivity rate was 7.5% for the week that ended Sept. 7, down from 8.4% for the week that ended Aug. 31.

“COVID-19 activity in San Francisco remains elevated, but not as high as the previous summer’s peaks,” the local Department of Public Health said.

Silicon Valley

In Santa Clara County, the coronavirus remains at a “high” level in the sewershed of San José and Palo Alto.

Roughly 1.3% of ER visits for the week that ended Sunday were attributed to COVID in Santa Clara County, down from the prior week’s figure of 2%.

Science

Early adopters of ‘zone zero’ fared better in L.A. County fires, insurance-backed investigation finds

As the Eaton and Palisades fires rapidly jumped between tightly packed houses, the proactive steps some residents took to retrofit their homes with fire-resistant building materials and to clear flammable brush became a significant indicator of a home’s fate.

Early adopters who cleared vegetation and flammable materials within the first five feet of their houses’ walls — in line with draft rules for the state’s hotly debated “zone zero” regulations — fared better than those who didn’t, an on-the-ground investigation from the Insurance Institute for Business and Home Safety published Wednesday found.

Over a week in January, while the fires were still burning, the insurance team inspected more than 250 damaged, destroyed and unscathed homes in Altadena and Pacific Palisades.

On properties where the majority of zone zero land was covered in vegetation and flammable materials, the fires destroyed 27% of homes; On properties with less than a quarter of zone zero covered, only 9% were destroyed.

The Insurance Institute for Business and Home Safety, an independent research nonprofit funded by the insurance industry, performed similar investigations for Colorado’s 2012 Waldo Canyon fire, Hawaii’s 2023 Lahaina fire and California’s Tubbs, Camp and Woolsey fires of 2017 and 2018.

While a handful of recent studies have found homes with sparse vegetation in zone zero were more likely to survive fires, skeptics say it does not yet amount to a scientific consensus.

Travis Longcore, senior associate director and an adjunct professor at the UCLA Institute of the Environment and Sustainability, cautioned that the insurance nonprofit’s results are only exploratory: The team did not analyze whether other factors, such as the age of the homes, were influencing their zone zero analysis, and how the nonprofit characterizes zone zero for its report, he noted, does not exactly mirror California’s draft regulations.

Meanwhile, Michael Gollner, an associate professor of mechanical engineering at UC Berkeley who studies how wildfires destroy and damage homes, noted that the nonprofit’s sample does not perfectly represent the entire burn areas, since the group focused specifically on damaged properties and were constrained by the active firefight.

Nonetheless, the nonprofit’s findings help tie together growing evidence of zone zero’s effectiveness from tests in the lab — aimed at identifying the pathways fire can use to enter a home — with the real-world analyses of which measures protected homes in wildfires, Gollner said.

A recent study from Gollner looking at more than 47,000 structures in five major California fires (which did not include the Eaton and Palisades fires) found that of the properties that removed vegetation from zone zero, 37% survived, compared with 20% that did not.

Once a fire spills from the wildlands into an urban area, homes become the primary fuel. When a home catches fire, it increases the chance nearby homes burn, too. That is especially true when homes are tightly packed.

When looking at California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection data for the entirety of the two fires, the insurance team found that “hardened” homes in Altadena and the Palisades that had noncombustable roofs, fire-resistant siding, double-pane windows and closed eaves survived undamaged at least 66% of the time, if they were at least 20 feet away from other structures.

But when the distance was less than 10 feet, only 45% of the hardened homes escaped with no damage.

“The spacing between structures, it’s the most definitive way to differentiate what survives and what doesn’t,” said Roy Wright, president and chief executive of the Insurance Institute for Business and Home Safety. At the same time, said Wright, “it’s not feasible to change that.”

Looking at steps that residents are more likely to be able to take, the insurance nonprofit found that the best approach is for homeowners to apply however many home hardening and defensible space measures that they can. Each one can shave a few percentage points off the risk of a home burning, and combined, the effect can be significant.

As for zone zero, the insurance team found a number of examples of how vegetation and flammable materials near a home could aid the destruction of a property.

At one home, embers appeared to have ignited some hedges a few feet away from the structure. That heat was enough to shatter a single pane window, creating the perfect opportunity for embers to enter and burn the house from the inside out. It miraculously survived.

At others, embers from the blazes landed on trash and recycling bins close to the houses, sometimes burning holes through the plastic lids and igniting the material inside. In one instance, the fire in the bin spread to a nearby garage door, but the house was spared.

Wooden decks and fences were also common accomplices that helped embers ignite a structure.

California’s current zone zero draft regulations take some of those risks into account. They prohibit wooden fences within the first five feet of a home; the state’s zone zero committee is also considering whether to prohibit virtually all vegetation in the zone or to just limit it (regardless, well-maintained trees are allowed).

On the other hand, the draft regulations do not prohibit keeping trash bins in the zone, which the committee determined would be difficult to enforce. They also do not mandate homeowners replace wooden decks.

The controversy around the draft regulations center around the proposal to remove virtually all healthy vegetation, including shrubs and grasses, from the zone.

Critics argue that, given the financial burden zone zero would place on homeowners, the state should instead focus on measures with lower costs and a significant proven benefit.

“A focus on vegetation is misguided,” said David Lefkowith, president of the Mandeville Canyon Assn.

At its most recent zone zero meeting, the Board of Forestry and Fire Protection directed staff to further research the draft regulations’ affordability.

“As the Board and subcommittee consider which set of options best balance safety, urgency, and public feasibility, we are also shifting our focus to implementation and looking to state leaders to identify resources for delivering on this first-in-the-nation regulation,” Tony Andersen, executive officer of the board, said in a statement. “The need is urgent, but we also want to invest the time necessary to get this right.”

Home hardening and defensible space are just two of many strategies used to protect lives and property. The insurance team suspects that many of the close calls they studied in the field — homes that almost burned but didn’t — ultimately survived thanks to firefighters who stepped in. Wildfire experts also recommend programs to prevent ignitions in the first place and to manage wildlands to prevent intense spread of a fire that does ignite.

For Wright, the report is a reminder of the importance of community. The fate of any individual home is tied to that of those nearby — it takes a whole neighborhood hardening their homes and maintaining their lawns to reach herd immunity protection against fire’s contagious spread.

“When there is collective action, it changes the outcomes,” Wright said. “Wildfire is insidious. It doesn’t stop at the fence line.”

-

Alaska1 week ago

Alaska1 week agoHowling Mat-Su winds leave thousands without power

-

Texas1 week ago

Texas1 week agoTexas Tech football vs BYU live updates, start time, TV channel for Big 12 title

-

Washington5 days ago

Washington5 days agoLIVE UPDATES: Mudslide, road closures across Western Washington

-

Iowa1 week ago

Iowa1 week agoMatt Campbell reportedly bringing longtime Iowa State staffer to Penn State as 1st hire

-

Miami, FL1 week ago

Miami, FL1 week agoUrban Meyer, Brady Quinn get in heated exchange during Alabama, Notre Dame, Miami CFP discussion

-

Iowa1 day ago

Iowa1 day agoHow much snow did Iowa get? See Iowa’s latest snowfall totals

-

Cleveland, OH1 week ago

Cleveland, OH1 week agoMan shot, killed at downtown Cleveland nightclub: EMS

-

World1 week ago

Chiefs’ offensive line woes deepen as Wanya Morris exits with knee injury against Texans