Science

Put a Bird on It? Ancient Egypt Was Way Ahead of Us.

A century ago, archaeologists excavated a 3,300-year-old Egyptian palace in Amarna, which was fleetingly the capital of Egypt during the reign of the pharaoh Akhenaten. Situated far from the crowded areas of Amarna, the North Palace offered a quiet retreat for the royal family.

On the west wall of one extravagantly decorated chamber, today known as the Green Room, the excavators discovered a series of painted plaster panels showcased birds in a lush papyrus marsh. The artwork was so detailed and skillfully rendered that it was possible to pinpoint some of the bird species, including the pied kingfisher (Ceryle rudis) and the rock pigeon (Columba livia).

Recently, two British researchers, Chris Stimpson, a zoologist at the Oxford University Museum of Natural History, and Barry Kemp, an archaeologist at the University of Cambridge, set out to identify the rest of the birds depicted in the panels. An attempt to conserve the paintings in 1926 backfired, causing some damage and discoloration, so Dr. Stimpson and Dr. Kemp had to rely on a copy made in 1924 by Nina de Garis Davies, an illustrator for the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Their findings were published in December in the journal Antiquity. Among the riddles they tried to solve was why two unidentified birds had triangular tail markings when no Egyptian bird known today has them.

For many millenniums, great flocks of birds have soared over Egypt on their twice-yearly passage between Europe and central and southern Africa. Beholding these migrations, ancient Egyptians regarded birds as living symbols of fertility, life and regeneration. With the possible exception of cats, no other animal has been so frequently drawn, painted or sculpted in Egyptian art.

Perhaps the most striking is the pied kingfisher, commonly called a helldiver, with its black and white plumage, shaggy topknot and slender beak. The bird hunts by hovering, hummingbird-like, above the water, head tilted steeply downward. On spying movement, the kingfisher folds its wings and becomes a speckled blur, plummeting headfirst below the surface and snatching prey with its long, pointed bill. The kingfisher abounds in Egyptian art; on the wall of the Green Room it appears amid the stems and umbels of a dense papyrus thicket at the moment it takes its helldive.

Pigeons, of course

The wild rock pigeon is the progenitor of the common domestic pigeon, that plump “rat of the sky” that flits from park bench to sidewalk to somewhere dangerously overhead. The painted panels show several rock pigeons, even though they are not native to Egypt’s papyrus marshes; rather, they prefer the region’s arid desert cliffs. Dr. Stimpson speculated that the birds were included in the swampy tableau to “enhance a sense of a wilder, untamed nature” and that they were drawn to the urban setting near the palace because the citizenry was feeding a nascent feral population. “In his religious doctrine, Akhenaten had a firm opinion about nature, which was supported and kept alive by Aten, the sun god that he claimed was the only true divinity,” said Manfred Bietak, an archaeologist with the Austrian Academy of Sciences. “This could explain why nature alone is depicted in the North Palace.”

Heaven scent

The Green Room, so named because of its dominant color, may have been designed to create a feeling of tranquillity for Akhenaten’s eldest daughter (and one of his younger wives), Meritaten, who lived there. “The room may have been adorned with perfumed plants and filled with soothing music,” Dr. Stimpson said, adding that “a masterpiece of naturalistic art would have added to the immersive sensory experience.” One particularly calming painting featured a perched bird with rich, chestnut plumage. The researchers have interpreted the creature as either a turtle dove (Streptopelia turtur), whose emollient purring has been described by one birder as “the color of ripening grain made audible,” or a red-backed shrike (Lanius collurio), known as the butcherbird for its habit of keeping a larder of food impaled on thorns.

A winter’s tail

Aided by an arsenal of previously published taxonomic and ornithological research, Dr. Stimpson and Dr. Kemp were able to identify the species that had been annotated with triangular tail markings. One is the red-backed shrike, a common autumn migrant in Egypt that often roosts in acacia trees. The other is the white wagtail (Motacilla alba), an abundant winter visitor. What accounts for the tail marks? The researchers believe that they may have been the artist’s way of indicating the season in which those birds appeared.

Science

Video: Axiom-4 Mission Takes Off for the I.S.S.

new video loaded: Axiom-4 Mission Takes Off for the I.S.S.

transcript

transcript

Axiom-4 Mission Takes Off for the I.S.S.

Hungary, India and Poland sent astronauts to the International Space Station for the first time by paying Axiom Space for the journey.

-

3, 2, 1, ignition and liftoff. The three nations, a new chapter in space takes flight. Godspeed Axiom 4.

Recent episodes in Science

Science

Contributor: Those cuts to 'overhead' costs in research? They do real damage

As a professor at UC Santa Barbara, I research the effects of and solutions to ocean pollution, including oil seeps, spills and offshore DDT. I began my career by investigating the interaction of bacteria and hydrocarbon gases in the ocean, looking at the unusual propensity of microbes to consume gases that bubbled in from beneath the ocean floor. Needed funding came from the greatest basic scientific enterprise in the world, the National Science Foundation.

My research was esoteric, or so my in-laws (and everyone else) thought, until 2010, when the Deepwater Horizon offshore drilling rig exploded and an uncontrolled flow of hydrocarbon liquid and gas jetted into the deep ocean offshore from Louisiana. It was an unmitigated disaster in the Gulf, and suddenly my esoteric work was in demand. Additional support from the National Science Foundation allowed me to go offshore to help figure out what was happening to that petroleum in the deep ocean. I was able to help explain, contextualize and predict what would happen next for anxious residents of the Gulf states — all made possible by the foresight of Vannevar Bush, the original architect of the National Science Foundation.

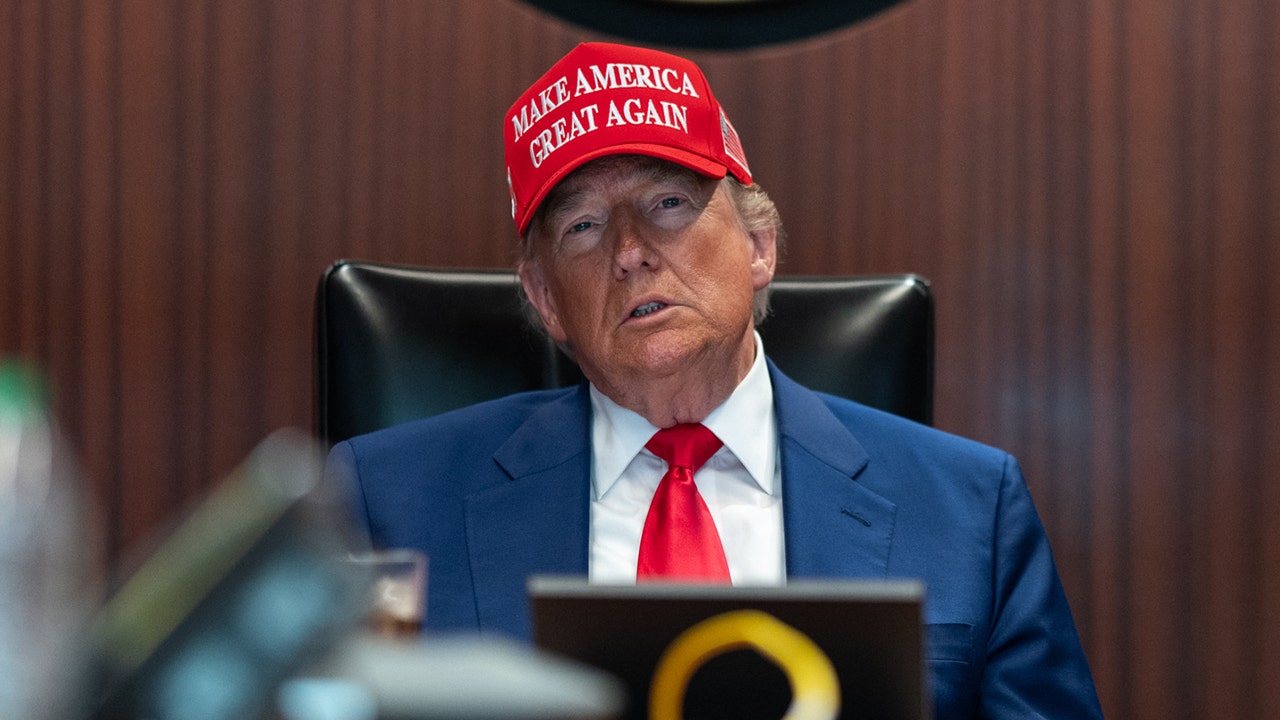

Now the great scientific enterprise that has enabled my research and so much more is on the brink of its own disaster, thanks to actions and proposals from the Trump administration. Setting aside the targeted cuts to centers of discovery such as Harvard and Columbia, and rumors that California’s public universities are next, the most obvious threats to research are the draconian budget reductions proposed across virtually all areas of science and medicine, coupled with moves to prevent foreign scientists from conducting research-based study in the U.S. The president’s latest budget calls for around a 55% cut to the National Science Foundation overall, with a 75% reduction to research support in my area. A reduction so severe and sudden will reverberate for years and decimate ocean discovery and study, and much more.

But a more subtle and equally dire cut is already underway — to funding for the indirect costs that enable universities and other institutions to host research. It seems hard to rally for indirect costs, which are sometimes called “overhead” or “facilities and administration.” But at their core, these funds facilitate science.

For instance, indirect costs don’t pay my salary, but they do pay for small-ticket items like my lab coat and goggles and bigger-ticket items like use of my laboratory space. They don’t pay for the chromatograph I use in my experiments, but they do pay for the electricity to run it. They don’t pay for the sample tubes that feed into my chromatograph, but they do support the purchasing and receiving staff who helped me procure them. They don’t pay for the chemical reagents I put in those sample tubes, but they do support the safe disposal of the used reagents as well as the health and safety staff that facilitates my safe chemical use.

They don’t pay salary for my research assistants, but they do support the human resources unit through which I hire them. They don’t pay for international travel to present my research abroad, but they do cover a federally mandated compliance process to make sure I am not unduly influenced by a foreign entity.

In other words, indirect costs support the deep bench of supporting characters and services that enable me, the scientist, to focus on discovery. Without those services, my research enterprise crumbles, and new discoveries with it.

My indirect cost rate is negotiated every few years between my institution and the federal government. The negotiation is based on hard data showing the actual and acceptable research-related costs incurred by the institution, along with cost projections, often tied to federal mandates. Through this rigorous and iterative mechanism, the overhead rate at my institution — as a percentage of direct research costs — was recently adjusted to 56.5%. I wish it were less, but that is the actual cost of running a research project.

The present model for calculating indirect costs does have flaws and could be improved. But the reduction to 15% — as required by the Trump administration — will be devastating for scientists and institutions. All the functions I rely on to conduct science and train the future workforce will see staggering cuts. Three-quarters of my local research support infrastructure will crumble. The costs are indirect, but the effects will be immediate and direct.

More concerning is that we will all suffer in the long term because of the discoveries, breakthroughs and life-changing advances that we fail to make.

The scientific greatness of the United States is fragile. Before the inception of the National Science Foundation, my grandfather was required to learn German for his biochemistry PhD at Penn State because Germany was then the world’s scientific leader. Should the president’s efforts to cut direct and indirect costs come to pass, it may be China tomorrow. That’s why today we need to remind our elected officials that the U.S. scientific enterprise pays exceptional dividends and that chaotic and punitive cuts risk irreparable harm to it.

David L. Valentine is a professor of marine microbiology and geochemistry at UC Santa Barbara.

Insights

L.A. Times Insights delivers AI-generated analysis on Voices content to offer all points of view. Insights does not appear on any news articles.

Viewpoint

Perspectives

The following AI-generated content is powered by Perplexity. The Los Angeles Times editorial staff does not create or edit the content.

Ideas expressed in the piece

- The article contends that indirect costs (overhead) are essential for research infrastructure, covering critical expenses like laboratory maintenance, equipment operation, safety compliance, administrative support, and regulatory processes, without which scientific discovery cannot function[1].

- It argues that the Trump administration’s policy capping indirect cost reimbursement at 15% would inflict “staggering cuts” to research support systems, collapsing three-quarters of existing infrastructure and crippling scientific progress[2][3].

- The piece warns that broader proposed NSF budget cuts—57% agency-wide and 75% in ocean research—threaten to “decimate” U.S. scientific leadership, risking a shift in global innovation dominance to nations like China[3].

- It emphasizes that these cuts ignore the actual negotiated costs of research (e.g., UC Santa Barbara’s 56.5% rate) and would undermine “discoveries, breakthroughs, and life-changing advances”[1].

Different views on the topic

- The Trump administration frames indirect costs as excessive “overhead” unrelated to core research, justifying the 15% cap as a cost-saving measure to redirect funds toward prioritized fields like AI and biotechnology[1][2].

- Officials assert that budget cuts focus resources on “national priorities” such as quantum computing, nuclear energy, and semiconductors, arguing that funding “all areas of science” is unsustainable under fiscal constraints[1][3].

- The administration defends its stance against funding research on “misinformation” or “disinformation,” citing constitutional free speech protections and rejecting studies that could “advance a preferred narrative” on public issues[1].

- Policymakers contend that reductions compel universities to streamline operations, though federal judges have blocked similar caps at other agencies (e.g., NIH, Energy Department) as “arbitrary and capricious”[2].

Science

How Bees, Beer Cans and Data Solve the Same Packing Problem

Animation of the same plastic spheres disappearing one at a time.

A holy grail in pure mathematics is sphere packing in higher dimensions. Almost nothing has been rigorously proven about it, except in dimensions 1, 2 and 3.

That’s why it was such a breakthrough when, in 2016, a young Ukrainian mathematician named Maryna Viazovska solved the sphere-packing problem in eight dimensions, and later, with collaborators, in 24 dimensions.

-

Arizona7 days ago

Arizona7 days agoSuspect in Arizona Rangers' death killed by Missouri troopers

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoAt Least 4 Dead and 4 Missing in West Virginia Flash Flooding

-

Culture1 week ago

Culture1 week agoBook Review: “The Möbius Book, by Catherine Lacey

-

Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoHow to build the best keyboard in the world

-

Movie Reviews1 week ago

Movie Reviews1 week ago10 Great Movies Panned Upon Release, From ‘The Thing’ to ‘Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me’

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoSen Padilla insists he wasn’t disrupting Noem press conference: ‘I was simply asking a question’

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoDriverless disruption: Tech titans gird for robotaxi wars with new factory and territories

-

Culture1 week ago

Culture1 week agoMatch These Books to Their Movie Versions