Science

Pregnant people can get a shot to protect babies from RSV, but some hit hurdles

When Megan Costello heard on the radio this fall that a newly approved vaccine for pregnant people could protect their babies from RSV, the Los Angeles resident immediately started asking how she could get the shot.

As a person with asthma, Costello said, she takes any kind of respiratory infection very seriously. So does her husband, whose family lost a child to pneumonia.

The one-time shot would protect her son against respiratory syncytial virus, which has long been the leading cause of hospitalization for infants in the United States.

But despite her eagerness to get vaccinated, the 38-year-old architect kept running into stumbling blocks — and ultimately missed her chance to get the shot while pregnant. Meanwhile, health officials were warning that another set of new immunizations for RSV — those given directly to infants — were in short supply.

Pediatricians “have been waiting for many decades to have an immunization to prevent RSV, and now we have two, but both have these huge barriers to delivery right now,” said Dr. Sean O’Leary, a pediatric infectious-disease specialist at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus who researches barriers to vaccination.

The shots have been hailed as a game changer for RSV, an illness that crowds pediatric wards in fall and winter and causes tens of thousands of young children in the U.S. to be hospitalized annually. The virus can sicken otherwise healthy infants and cause pneumonia and inflammation of the small airways in the lungs. According to estimates from the national Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, RSV leads to the deaths of 100 to 300 children under age 5 in the U.S. each year.

A 16-month-old old patient with RSV is cared for at Loma Linda University Children’s Hospital last winter.

(Francine Orr / Los Angeles Times)

But babies can now be protected from RSV in two ways: They can be immunized with an antibody called nirsevimab, or their mothers can get a vaccine called Abrysvo during a specific window in the third trimester of pregnancy and pass protection on in utero. (The shot was initially recommended for seniors and became available to pregnant people this fall.)

Most babies need only one or the other, and amid a shortage of nirsevimab, the CDC has urged medical providers to encourage pregnant people to get vaccinated. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends Abrysvo for patients who are between weeks 32 and 36 of pregnancy from September to January, the time of year when RSV spreads.

Yet some pregnant patients eager to get vaccinated have met with obstacles. Computer systems at some pharmacies initially balked at booking shots for the newly eligible patients, pregnant women reported. Insurers are not required to cover newly approved vaccines right away. And medical offices and pharmacies did not necessarily have the shot on hand.

“It has taken many months for people to be able to find it reliably at local pharmacies,” and it’s still rare to get it at a doctor’s office, said Dr. Mya Zapata, an OB-GYN at UCLA Health. The vaccine’s availability “wasn’t clear and transparent,” and many patients had to call around or rely on word of mouth to find it.

Such hiccups are not unusual for a new vaccine, but three factors have made them especially frustrating in the case of the RSV shot, experts said: Pregnant people have only a limited window in which to get the vaccine. There has been a shortage of another shot that could otherwise protect newborns. And federal officials didn’t officially recommend the vaccine for pregnant patients until late September, when RSV was already on the rise.

Vaccine rollout issues usually are worked out within a few months, but “this is a seasonal vaccine,” said Dr. Kevin Ault, an OB-GYN at the Western Michigan University Homer Stryker M.D. School of Medicine. “If it’s all settled by the end of January, that doesn’t really help us that much.”

O’Leary, of CU Anschutz, pointed to a host of early challenges in getting the vaccine to pregnant patients. Priced at roughly $300, the new shot is expensive for clinics, which typically have to buy a vaccine, administer it to a patient, then bill the patient’s insurance for payment. Under federal law, private insurers have at least a year after CDC officials recommend a new vaccine to cover it, and “with such an expensive product, that puts [clinics] at serious financial risk,” he said.

As pregnant patients are directed to pharmacies, other obstacles can arise. Among them: There are two RSV vaccines for adults, but only one can be given to pregnant patients — and some pharmacies may not be stocking it.

Pharmacies may choose not to administer particular vaccines for a range of reasons, said Dr. Dima Qato, an associate professor at the USC Mann School of Pharmacy. Some might not have been immediately aware of the new recommendations to give the shot to pregnant patients, while others may not have been equipped to screen them for eligibility.

For a pharmacy, there’s the question of “how would you confirm a woman is 32 to 36 weeks pregnant,” Qato said. “It’s much easier for a vaccine that has no restrictions, like COVID or the flu, for a pharmacy to administer it.”

Costello, the pregnant architect with asthma, said a retail pharmacy initially told her it was only offering the shot to people 60 and older, the group that had first been eligible for the RSV vaccine. After she got a prescription from her obstetrician, the pharmacy was willing to give her the shot, but warned that her insurance would not cover it and she’d have to pay more than $350, Costello said.

Despite her best efforts, Megan Costello was unable to get the recommended RSV shot while she was pregnant.

(Francine Orr / Los Angeles Times)

She and her friends traded stories via text about their struggles to get vaccinated. “My doctor literally said some insurance is refusing to pay and her patients are getting charged $300+,” one of her friends wrote.

Costello said she phoned her insurer and was told her plan would only cover the vaccine if it was administered by a doctor in their office. So she booked an appointment with her primary care doctor, only for it to be canceled because it was against the practice’s policy to give vaccines in the office, she was told.

“Why are they even recommending this if it’s so inaccessible??” another friend texted when Costello told her the appointment had been canceled.

In Van Nuys, Rachel Palmer had little time left to get the vaccine when the CDC endorsed it for mothers-to-be. Her doctor sent her with a note to a local pharmacy, but “their system wouldn’t even make it a possibility for me to have it” because she was under 60, she said.

“It is frustrating that my doctor was recommending it. The pharmacist had it. The pharmacist saw that the CDC recommended it. And it was just a computer program that stopped me from getting it,” said Palmer, 36, whose second child was born in October.

After the birth, her newborn had the option of getting the infant RSV immunization, but the shot was not yet covered by the family’s insurance, Palmer said. As a writer who’s been on strike this year, she has wrestled with whether her family can afford to pay hundreds of dollars out of pocket.

Zapata, at UCLA Health, said some insurers have insisted on prior authorizations for the shots, “which then delays the patient and puts them out of the window to get the vaccine.”

It is unclear how many pregnant people have been vaccinated. The CDC said it does not yet have enough data to include the maternal vaccine on its public dashboard for RSV vaccination coverage. The California Department of Public Health also said it didn’t have confirmed data.

Vaccination rates for other seasonal shots recommended for pregnant patients have lagged in recent years, but many people jumped at the opportunity to get the RSV vaccine. One woman in Maryland said she was excited when the shots were announced in September.

“I was having a baby in November — the peak of cold and flu and RSV and all of those things — and I was going to have an opportunity to protect him,” said the woman, who asked not to be named to prevent harassment over her vaccination decisions. But “it seemed like nobody in the pharmacy industry had gotten the memo.”

One pharmacy told her its system wouldn’t process the RSV shot due to her birth date, she said. Another told her to make an online appointment, but its system balked for the same reason.

She phoned the Maryland Department of Health, but said she couldn’t reach anyone there who could help her. She called more pharmacies and was told they didn’t have the vaccine. The woman then turned to a Reddit forum about pregnancy for advice, and eventually got vaccinated at a grocery store pharmacy.

“I was hellbent on getting this shot and managed to get it,” the woman said. “But for a lot of people who don’t have the time or resources that I had to dedicate to finding the shot, they’re missing out.”

Several doctors say that early headaches like hers seem to have eased. Representatives for Rite Aid, Walgreens and CVS said their pharmacies now offer the vaccine to pregnant patients who are in the eligible window.

“I haven’t heard any issues from patients about coverage, nor about getting it from their local pharmacy” in recent weeks, said Dr. Roxanna A. Irani, a maternal-fetal medicine specialist at UC San Francisco. “Certainly we have it in our clinic.”

If the vaccine had been approved earlier, problems might have been resolved before RSV season, “but I’m happy to have it now,” Irani said. “The uptake has been unbelievable. Patients the very first day were sending us messages, bombarding our nursing lines with questions about it.”

“It’s not even about them — they’re getting it to protect their newborn,” she added.

In Van Nuys, Palmer was alarmed when her older child tested positive for RSV. She’s trying to keep the toddler away from her newborn.

“We’re obviously very nervous” for the baby, she said. “And I really wish I had gotten that vaccine!”

Science

Is bird flu in cattle here to stay?

Despite assurances from the federal government that bird flu will be eradicated from the nation’s dairy cows, some experts worry the disease is here to stay.

Recently, Eric Deeble, USDA acting senior advisor for H5N1 response, said that the federal government hoped to “eliminate the disease from the dairy herd” without requiring vaccines.

Since the disease was first publicly identified in dairy cattle on March 25, there have been 129 reports of infected herds across 12 states. In the last four weeks, there has been a surge — jumping from 68 confirmed cases on May 28 to nearly twice that many as of June 25. There are no cases in California.

So far, however, the dairy industry has proved reluctant to work with state and federal governments to allow for widespread testing of herds.

To some epidemiologists, this lack of close herd surveillance is a problem. They worry that the virus is spreading unchecked among dairy cows and other animals, and has taken up permanent residence.

David Topham, a professor of microbiology and immunology at the University of Rochester’s Center for Vaccine Biology and Immunology, said he considers H5N1 to be “endemic in animals in North America” — citing its prevalence in wild bird populations as well as its long staying power in domestic poultry.

No one knows how widespread it is in cattle, Topham said, because testing has largely targeted symptomatic cows and herds. “But I suspect the closer we look, the more we’ll find, and I don’t know if we’re going to cull our entire cattle herds and start over again.”

Topham said he understands the industry’s reluctance to permit government scientists onto farms “because we’re going to want to see everything, and we’re going to report everything that we see, and that might be bad for business. … But until we have all that information, I don’t think we will have control.”

Federal officials have announced a pilot bulk milk testing program that includes Kansas, Nebraska, New Mexico and Texas. Farmers in these states can voluntarily enroll to have bulk milk samples tested for the virus. If their samples test negative for three weeks, they will be able to move their herds across state lines without additional testing — something they are currently unable to do.

So far, only one herd in each state has signed up.

A USDA “strike force” investigated 15 infected Michigan dairy herds as well as eight turkey flocks in early April. It worked with the state of Michigan as well as individual farmers.

The investigation was launched after local researchers identified a “spillover” event that went from infected cattle to a nearby poultry plant. The state — and farmers — wanted to know how it happened.

What the team found suggests the “control” Topham referred to may be elusive.

From surveys and observations, they found that cats and chickens were free to walk around without containment — potentially migrating between nearby dairies and poultry farms. Some of these animals had become infected; several died.

Asked about their practices regarding isolation of newly introduced cattle, three out of 14 farms said they always isolated, another three said they never isolated, and the remainder didn’t respond.

Then there was the dumping of unpasteurized, contaminated milk into the open waste lagoons on several of the farms. And the feeding of non-pasteurized milk to calves on three farms. Or the potentially contaminated manure that was stored, composted or applied to nearby fields. In one case, a farmer reported they had sold or given away potentially contaminated manure.

Finally there was the issue of humans: On every farm, there were visitors, carcass removal companies, milk suppliers, veterinarians and employees — many of whom traveled between farms.

For instance, of the 14 dairies that reported information about their employees, three had employees that worked at other dairies, one had employees that worked at a poultry farm, and one had an employee who also worked at a swine farm. At four dairies, some of the employees were reported to have their own livestock at home.

As the authors reported, “transmission between farms is likely due to indirect epidemiological links related to normal business operations … with many of these indirect links shared between premises.”

They noted there was no evidence to suggest waterfowl had introduced the virus to the Michigan herds.

Michael Payne, researcher and outreach coordinator at UC Davis’ School of Veterinary Medicine Western Institute for Food Safety and Security, said there was no one to blame for the lack of containment.

He said in the weeks and months before the disease was identified in cattle, researchers from across the nation scrambled to figure out what was happening to dairy cows in Texas that appeared listless and had diminished milk production.

“It’s not like people weren’t aware or concerned and trying to figure it out,” he said. And then once it was identified, and it didn’t seem to cause too much illness in cows or transfer to humans quickly, while there was urgency, the system fell into a series of “incremental” solutions — negotiated among dozens of federal and state agencies.

He and Topham agree that no one can say for sure what the virus will do — and where it will go — next.

If it becomes endemic in cattle and is renamed “bovine influenza,” vaccines are likely to follow, as well as continuous surveillance and testing of dairy products.

Topham said that the biggest concern among epidemiologists now is how the virus will evolve as it continues to move — largely unabated and undetected — through cattle herds, resident farm animals and people.

There have been three human cases of H5N1 in U.S. dairy workers since March.

One key worry is that the virus may move with a dairy employee onto a small farm and then recombine inside a pig, dog or cat that is harboring another flu virus.

He and Payne agree that officials need to remain alert to signs that the virus is adapting in ways that could hurt humans.

Wastewater is one way to detect the location of the virus.

As of Tuesday, data from the academic research organization WastewaterSCAN show that levels of H5 influenza have been rising in wastewater samples from a facility in Boise, Idaho.

Asked about whether the region’s health department was investigating, or if there was any idea where the H5 was coming from, Surabhi Malesha, communicable disease program manager at Central District Health in Idaho, said there was no way to know if the H5 signal was from H5N1 or another influenza subtype.

She said testing for H5 in wastewater had only recently started and therefore “there is no way to compare this data from last year or the year before, and so we don’t know what a baseline detection of H5 looks like.”

“Maybe we see H5 detections like this on a regular basis, and it is not of public health significance or importance. … How do we define normalcy when we have nothing to compare the data to?”

She said the findings were “not a public health concern” and her agency and the state “do not need to really investigate into this, because this could be H5N1, or could be any other H5 strains, and it really does not affect the public in general.”

Dennis Nash, distinguished professor of epidemiology and executive director of City University of New York’s Institute for Implementation Science in Population Health, said that given the current situation, the wastewater sample should be considered H5N1 “until proven otherwise. The only other H5 we know about is H5N2. And a man in Mexico City just died from that.”

Nash said health officials should be trying to determine the source of the virus found in the wastewater: a nearby dairy herd, a milk processing site or raw milk that was dumped down the drain.

Idaho has reported 27 infected herds, although according to Malesha, none has been reported in the Central District.

“You want to do everything you can to prevent these types of viruses from emerging, because once they do, we don’t have a whole lot of control over them,” Topham said. “Because when the horse is out of the barn, it’s gone. So I think the question is, what do we need to do to keep this in check?”

Science

The desperate hours: a pro baseball pitcher's fentanyl overdose

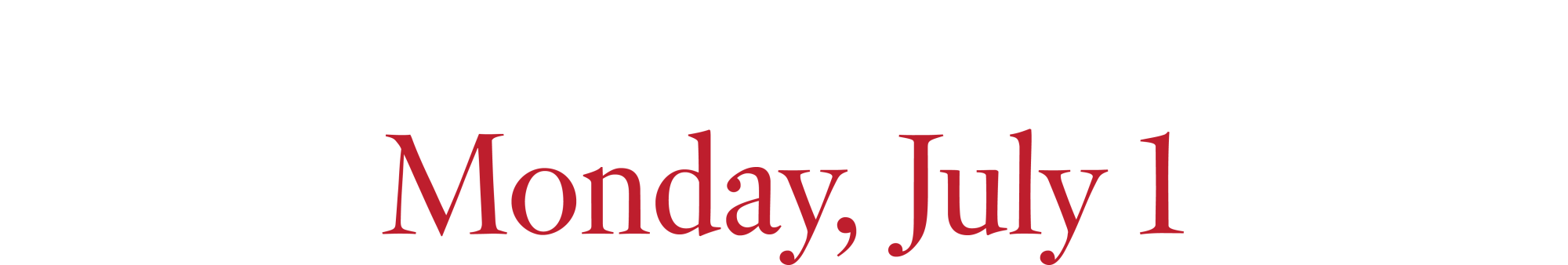

Not many victims of the opioid crisis in America make national headlines. Tyler Skaggs was different.

The 27-year-old was a professional athlete, a pitcher for the Angels, wealthy and famous. On a road trip with the team, he was found in his hotel room. He had choked on his own vomit after consuming a mix of alcohol, oxycodone and fentanyl.

His death on July 1, 2019, sent shock waves through the sports world. A highly publicized criminal investigation not only revealed that Skaggs had secretly used painkillers for years, but also led to the arrest of a team employee accused of providing him with tainted, black market pills.

Five years later, The Times has pored over hundreds of pages of court documents and cellphone records to reconstruct Skaggs’ final hours. Playing cards with teammates on a three-hour flight. Teasing rookies on the bus. Trading affectionate texts with his wife until late at night.

Even the most ordinary details tell an important story, offering an intimate look at an epidemic that has ravaged the country.

Tyler Skaggs pitches against the Oakland Athletics on June 29, 2019, two days before his death.

(Marcio Jose Sanchez / Associated Press)

Skaggs pitches at Angel Stadium against the Oakland A’s and is pulled after surrendering two runs in four-plus innings. CAA agent Nez Balelo texts to commiserate about “the quick hook … after cruising basically through 3 and 4.”

Skaggs is nothing if not dogged. At 6 feet 4 and 225 pounds, he has fought back from a string of serious injuries, refusing to quit, which might help explain his painkiller use. After the game, his mother, Debbie Hetman, a longtime softball coach at Santa Monica High, calls him and his wife.

“I didn’t FaceTime him because I was – we were super busy, so we just talked really quickly,” Hetman later testifies during the team employee’s trial. “I think he was in line at In-N-Out with Carli.”

Mike Trout, wearing Tyler Skaggs’ number in his honor, speaks to Eric Kay in the dugout before a July, 12, 2019, home game against the Seattle Mariners.

( John McCoy / Getty Images)

(Animation by Kelvin Kuo/Los Angeles Times)

Shortly before a 1:07 p.m. game against the A’s, Skaggs receives a text from Eric Kay, the team communications director who for years has allegedly supplied him with “blue boys” — blue, 30-milligram oxycodone pills.

Kay: “Hoe [sic] many?”

Skaggs: “Just a few like 5”

Kay: “Word”

Skaggs: “Don’t need many”

4:25 p.m. Pacific Time

The Angels conclude their four-game home series with a 12-3 loss. It is a get-away day, meaning the team will head directly from the stadium to Long Beach Airport, where a charter plane waits for the start of the road trip.

Skaggs has previously asked his manager’s permission for the players to dress like cowboys for the flight to Texas. Before leaving the stadium, he meets his wife, Carli, so she can snap pictures of him in his black hat, bolo tie and boots.

“When did he buy that outfit?” a prosecutor later asks her during Kay’s trial.

“The day before.”

“Did you help him pick it out?”

“Yes.”

6:11 p.m. PT

Skaggs gathers with teammates on the tarmac beside a United Airlines charter plane for another photo to show off their Western wear. He hitches his thumbs in his belt like a cowboy. Seeing the picture on Instagram, Carli comments: “So cute”

8:07 p.m. PT

(Animation by Kelvin Kuo/Los Angeles Times)

With the Texas Rangers next on the schedule, the flight to Dallas Fort Worth International Airport lasts about three hours. Along the way, Carli texts to ask how things are going.

Skaggs: “Good gambling … losing”

Carli: “Damn babe … How much cool … Lol*”

Skaggs: “200 bucks … I’m winning now”

Carli: “Sweet”

11:06 p.m. Central Time

On the 15-minute ride from the airport to a Dallas-area hotel, Skaggs grabs a microphone at the front of the bus.

“So, he would have been kind of like emceeing, doing the music,” teammate Andrew Heaney later testifies. “You know, we would call younger guys up, ask them, you know, embarrassing questions or make them tell a funny story or whatever it may be, make them sing a song, something like that.”

Throughout the league, Skaggs is known as friendly, funny, eminently likable. Teammate Mike Trout later says: “The energy he brought to a clubhouse … every time you saw him, he’s just picking you up.”

11:25 p.m. CT

The Angels arrive at the Hilton Dallas/Southlake Town Square, where players receive key cards to their rooms and peruse a table of snacks, protein bars and Gatorade. A friend invites Skaggs to go out, but the pitcher remains in his room.

11:47 p.m. CT

(Animation by Kelvin Kuo/Los Angeles Times)

Skaggs texts his room number to Kay.

“469,” he writes, adding: “Come by”

“K,” the communications director responds.

Kay had used opioids enough to know black market oxycodone pills might be laced with dangerous drugs such as fentanyl, a synthetic opioid 50 to 100 times more powerful than morphine. In a jailhouse call recorded after his trial, he denies giving drugs to Skaggs that night, saying he visited the pitcher to talk about something else.

“I guess he hated the rookies or something — and he was one flight up so I flipped my door and went up,” he says.

The hotel does not have security cameras in the hallway, so it is unclear how long Kay spends in room 469.

12:02 a.m. CT

(Animation by Kelvin Kuo/Los Angeles Times)

Skaggs texts with teammate Ty Buttrey. He then trades messages with his wife.

Skaggs: “Miss you babe”

Carli: “Miss u too”

When the two met in 2013, Skaggs reportedly fell hard. Now, they have a house and are thinking about kids. They text continually when the Angels are traveling.

12:42 a.m. CT

“What u Doin,” Carli asks.

No answer. She tries again: “Helllooooo.”

1:09 a.m. CT

It is late in Dallas — two hours later than Los Angeles — and Carli is still waiting for a “goodnight” from her husband. She writes: “U know better than to get drunk and fall asleep without texting me”

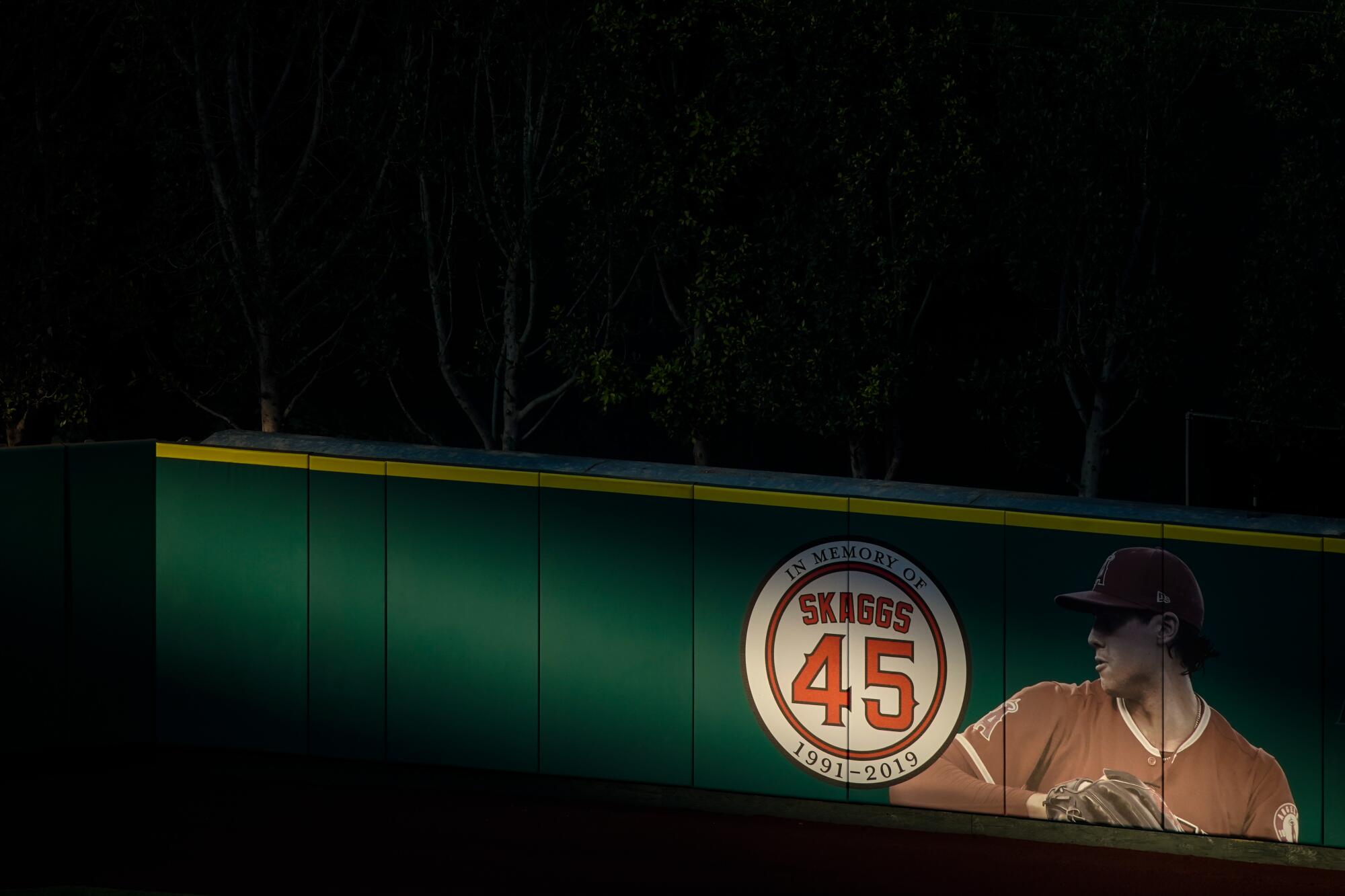

Approx. 12:53 p.m. CT

Angels’ Mike Trout, left, embraces Andrew Heaney, who fights back tears as he answers questions about their late friend and teammate Tyler Skaggs.

(Tony Gutierrez / Associated Press)

The night passes, followed by morning, and still no word from Skaggs. Heaney texts him: “Lunch?”

After a few minutes, Heaney stops by room 469. Light shines from under the door; the curtains must be open in there. Nearby, hotel workers are noisily cleaning a carpet. Heaney wonders how anyone could sleep through all this.

When his knock gets no response, he goes back to his room and tries calling Skaggs on the hotel phone.

1:49 p.m. CT

Tom Taylor, the Angels traveling secretary, is having lunch with Kay at a nearby barbecue joint and recalls Carli texting him. Heaney also reaches out to Taylor.

“He hadn’t heard from him either,” Taylor later testifies.

More than 12 hours after Carli’s last exchange with her husband, she messages again: “You have a drinking problem. I’m about to text tom Taylor.”

Carli later insists these words were sent “purely out of anger” with “no truth to it.”

Irritation gives way to another emotion. Carli contacts Skaggs’ mother, Hetman.

“She was really nervous,” Hetman later testifies. “I was really nervous because it was very unusual not to hear back from Tyler. Tyler was very good about returning text messages.” Hetman dials his number, and it sounds as if the call goes directly to voicemail. Her husband, Dan Ramos, sends a text:

“Hi kid. How r u doing. How is life treating u. How is your arm feeling”

A photo of Tyler Skaggs and his wife, Carli, is displayed outside a memorial service for the Angels pitcher in 2019.

(Christina House / Los Angeles Times)

2:04 p.m. CT

Now Hetman tries texting: “Hey Ty Are you okay today?”

Around the same time, Taylor returns to the hotel and knocks on Skaggs’ door. He then summons Chuck Knight, one of the team’s security men, and they ask hotel management to let them into room 469.

A former Anaheim Police Department officer, Knight enters the room alone, staying less than a minute. Taylor later recalls him emerging with “a shocked-looking face, almost like, it’s not good, what he saw.”

2:16 p.m. CT

Knight calls 911. Asked later about what he encountered in the room, he testifies: “I saw two legs hanging off the end of the bed in a position that I thought was unusual for someone that might be sleeping … I walked closer in an attempt to obtain a pulse. I reached down to grab his wrist and noticed that his skin was very cool to the touch. I did not obtain a pulse.”

Heaney, who is getting messages from Carli, returns to the hallway outside room 469. Taylor tells him: “It’s not good.”

“I knew what was going on, but his wife didn’t,” Heaney later testifies. “And she was texting me, so it was — I just felt like I wanted her to know what was going on.”

He decides not to answer.

A call crackles over the scanner: “Medic 4-1, truck 4-1 respond. Medical emergency, Hilton Southlake Town Square.” The dispatcher adds: “It’s gonna be … a possible death investigation. PD is arriving on scene now.”

A Southlake police officer finds Skaggs’ room looking mostly undisturbed — the bed still made, a backpack and another bag on the couch, unopened beers on the coffee table. There is a white, “almost chalky” substance on the desk. Skaggs’ cellphone lies near his head.

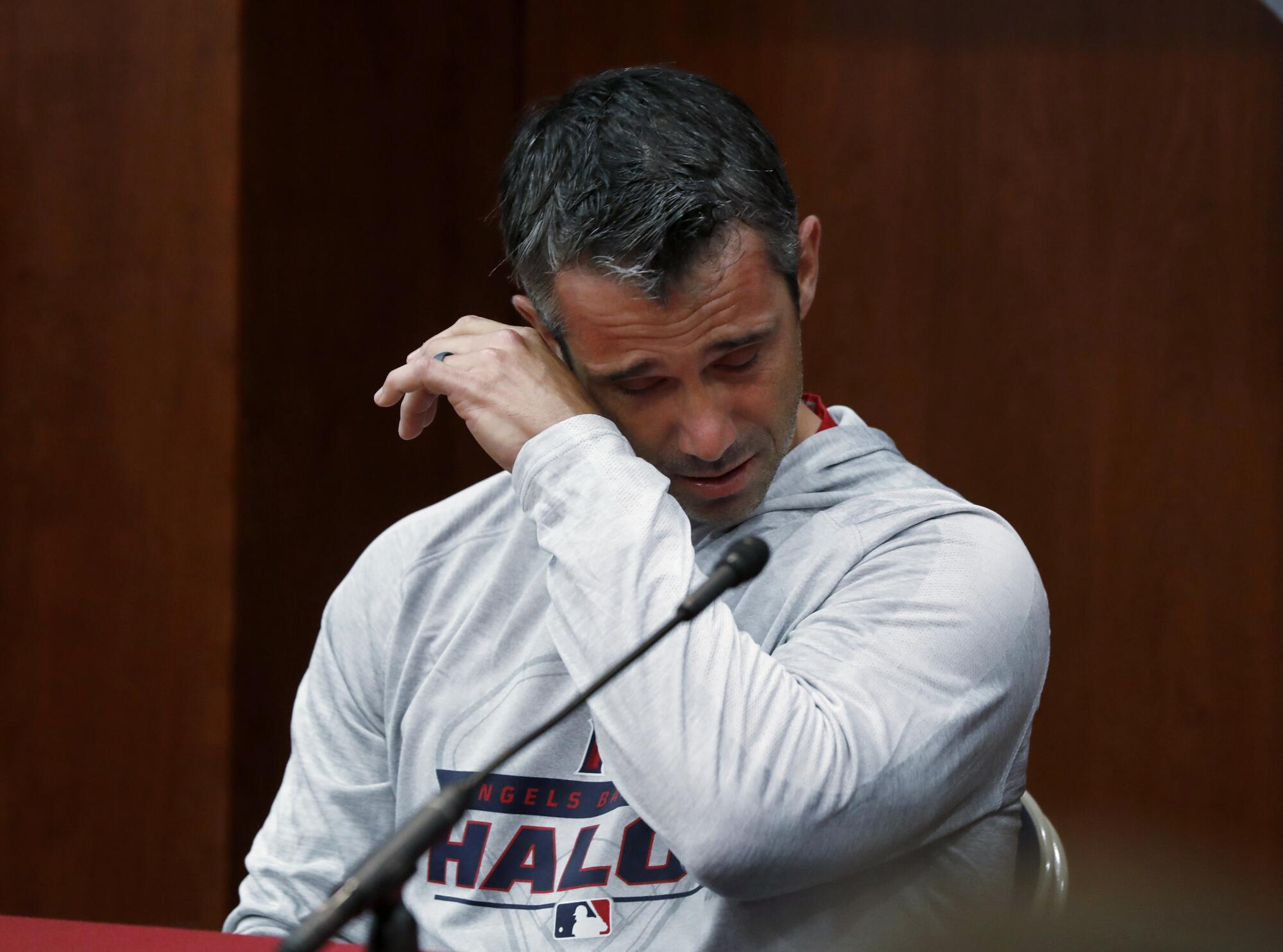

A memorial for Tyler Skaggs on the outfield wall at Angel Stadium.

(Los Angeles Times)

2:23 p.m. CT

Cory Teague, a Southlake Fire Department paramedic, arrives at room 469. His medical supplies include Naloxone, which can be administered to reverse the effects of opioid overdose.

“Did you use it?” a prosecutor later asks at trial.

“No.”

“Why not?”

“The patient had signs incompatible with life, unable to be revived.”

3:05 p.m. CT

Carli’s phone rings as she pulls up to her parents’ house in Santa Monica. It’s Billy Eppler, the Angels’ general manager. “I’ll never, ever forget that call,” she later says. She dials Hetman, who is at her Los Angeles home, and breaks the news. Hetman later recalls “crying and yelling and screaming.”

Buses are scheduled to take the Angels to their evening game. Instead, players and staff are told of Skaggs’ death and shepherded into a hotel banquet room where police take statements.

“The questions that we asked were generic for each player and employee,” Cpl. Delaney Green of the Southlake Police Department later testifies. “And it was along the lines of: When was the last time that you had seen or spoken to Tyler Skaggs? Had you seen him consume any alcohol on the plane? And did you know of any drug use that you were aware of?”

Kay is among those interviewed. He tells police that Skaggs was drinking on the flight to Texas but adds, “I didn’t think he had a lot.” He says he last saw the pitcher when they collected their room keys in the lobby.

3:52 p.m. CT

The Times and other news agencies report Skaggs’ death on social media. Family members call his mother at home. She later testifies that “before I could even talk to anybody, that whole — everything was like blowing up and it was super-crazy.”

4:11 p.m. CT

Angels manager Brad Ausmus speaks at a 2019 news conference about Tyler Skaggs’ death.

(Tony Gutierrez / Associated Press)

The Rangers announce the postponement of that night’s game as the Angels switch to another hotel. The team gathers for an emotional meeting. “We were able to talk about Tyler and laugh at some of the stories and some of the goofy things he did, listen to some of his music,” manager Brad Ausmus later says before breaking down.

On social media, players from around the league post messages.

“RIP to my longtime friend and Little League teammate,” then-St. Louis Cardinals pitcher Ryan Sherriff writes. “i love you brotha.”

About 8 p.m. CT

Carli and the Skaggs family board a flight to Texas.

About 10 a.m. CT

Carli and the Skaggs family visit the medical examiner’s office in Fort Worth. She later recalls kissing her husband’s cold lips as he lay on a gurney.

11:10 a.m. CT

The medical examiner begins an autopsy. He will eventually determine that “alcohol, fentanyl and oxycodone intoxication” caused Skaggs to choke on his own vomit.

Later that morning, Carli and the Skaggs family arrive at the Southlake police station to retrieve his luggage, iPad and other belongings.

In words that underscore the anguish of losing a loved one to opioids, Hetman later testifies: “I was angry because I knew that my son loved life and he did not want to die. He did not know that there was poison in that pill that cost him his life.”

About 5:30 p.m. CT

Team officials hold a news conference with Kay standing quietly to the side, hands clasped at his waist. At one point, he appears to take a deep breath, look toward the ceiling and exhale.

7:05 p.m. CT

Teammates place jerseys with Tyler Skaggs’ number 45 on the mound at Angel Stadium at their first home game after his death.

(Kent Nishimura / Los Angeles Times)

The game against the Rangers proceeds as scheduled. The ballpark is eerily quiet, with the home team forgoing the usual walk-up music.

The Angels, wearing black No. 45 patches on their jerseys, score early and cruise to a surprising 9-4 victory, but Trout says: “All I was thinking about was Tyler. It was just a different feeling, you know. Just shock.”

Angels pitcher Tyler Skaggs died of an overdose in a hotel room on July 1, 2019.

(K.C. Alfred/San Diego Union-Tribune)

Federal prosecutors charged Kay with distribution of a controlled substance resulting in death and conspiracy to possess with intent to distribute controlled substances. A trial began in February 2022.

“This was a case of one, one person who went up to that room on June 30,” a prosecutor said in court. “One person who went into that room and gave Tyler Skaggs fentanyl.”

The jury deliberated less than 90 minutes before returning a guilty verdict on both counts.

At a hearing where the judge sentenced him to 22 years in federal prison, Kay — who didn’t testify during trial — apologized to his family for the “disgrace and embarrassment” he had caused them.

Privately, however, he continued to profess innocence. In a recorded jailhouse call, he told a friend: “The worst thing, though, is that text that he sent me … because I didn’t know what he wanted. I had no idea. In my head, I think he thought I already got more [pills] for him but I told him they were going to be s—.”

By then, the Skaggs family had filed a wrongful-death suit against the Angels. The team has denied wrongdoing, and the case continues.

In the five years since Skaggs died, opioid overdoses — fueled by illicitly manufactured pills — have claimed hundreds of thousands of American lives.

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration has a 24-hour helpline for individuals and families facing mental and substance abuse disorders. The number is (800) 662-HELP (4357).

Science

10 sunscreen myths you can't afford to fall for

Attention sunscreen skeptics: The sun’s UV rays are coming for you, and you’re just making their job easier.

Summer is now upon us, which means more time in the sun — and more exposure to the ultraviolet radiation it emits. Longer-wavelength ultraviolet A rays can reach beneath the skin’s surface, causing it to age prematurely. Shorter-wavelength ultraviolet B rays affect the outermost layers of skin, causing sunburns and tans. (A third type of rays, ultraviolet C, is intercepted by Earth’s protective ozone layer.)

Both UVA and UVB damage the DNA in skin cells, causing mutations. These mutations can accumulate over time and cause tumors to grow. The more UV exposure you have, the greater the risk, according to the Skin Cancer Foundation.

Basal cell carcinoma is the most common type of skin cancer in the United States, followed by squamous cell carcinoma. About 5.4 million of these cancers combined are diagnosed each year, and they cause between 2,000 and 8,000 deaths, the American Cancer Society says.

Melanoma of the skin is both more rare and more deadly, affecting an estimated 100,640 Americans this year and resulting in 8,290 deaths, according to the National Cancer Institute.

Sunscreens can protect you from these malignancies in one of two ways. Chemical sunscreens contain ingredients such as avobenzone that absorb UV rays. Mineral sunscreens rely on zinc oxide or titanium dioxide to block or reflect the rays. Either way, the solar radiation is unable to penetrate the skin and corrupt your DNA.

Here are 10 sunscreen myths you can’t afford to fall for:

Myth 1: As long as you don’t get a sunburn, you’re safe.

The reality: You don’t need to get a sunburn to put your skin at risk. UV exposure will compromise the DNA of unprotected skin — even if your skin looks normal to the naked eye — and the effects are cumulative, said Dr. Henry Lim, a photodermatologist at Henry Ford Health in Detroit who studies the effect of sunlight on skin.

“Each time the skin is damaged by the sun, with or without sunburn reaction, there is some damage that the skin would have to repair,” Lim said. “If that subclinical damage goes on often enough for a long enough period of time, the skin’s ability to be able to completely repair all that DNA damage will be compromised.”

Myth 2: Your body needs vitamin D, and sunscreen will keep you from getting it.

The reality: It only takes a small amount of sun exposure to produce all the vitamin D your body needs. One study of white people in the Boston area determined that 5 to 10 minutes of sun on the face, arms and legs two or three times a week during the summer months was enough to produce sufficient amounts of vitamin D.

Even if you apply sunscreen, you’ll still get that minimum amount of sun exposure, Lim said. “When we use sunscreen, we don’t apply enough,” he said. “It’s just human nature.”

Dr. Anne Chapas, a dermatologist in Manhattan and clinical instructor at Mt. Sinai Medical Center, advises patients who are concerned about their vitamin D levels to protect their skin and seek out the nutrient in foods or take supplements.

“You do need vitamin D to be healthy, but there are multiple ways to get it,” she said.

Myth 3: The chemicals in sunscreen can cause cancer.

The reality: The active ingredients in sunscreens sold in the U.S. are regulated by the Food and Drug Administration, which has determined that they are safe and effective. The National Academies add that “sunscreen use is not linked to higher rates of any type of cancer.”

In fact, it’s the reverse that’s true, Chapas said: “If you’re trying not to get cancer, then wear sunscreen.”

Los Angeles Dodgers first baseman Freddie Freeman sprays sunscreen on his face. Dermatologists recommend spraying it into your hand and then applying it to your face instead.

(Robert Gauthier/Los Angeles Times)

Myth 4: You don’t need to wear sunscreen when the UV index is low.

The reality: The UV index primarily measures UVB, which Lim calls “the sunburn spectrum.” Even if UVB is low, you still need to protect yourself from UVA.

“As long as there is light out there, there’s enough UVA” to induce tanning, cause wrinkles, and contribute to skin cancer risk, Lim said.

Chapas concurred. “Even on cloudy days, about 80% of the sun’s rays come through and you can can still get sun damage,” she said.

Myth 5: You don’t need sunscreen if you have dark skin.

The reality: People of every complexion can get sun damage and skin cancer. In fact, “skin cancer in patients with darker skin tones is often diagnosed in later stages, when it’s more difficult to treat,” said Dr. Seemal Desai, president of the American Academy of Dermatology.

Chapas added that since darker skin is apt to produce melanin in response to sun exposure, it may become discolored more readily than lighter skin.

Myth 6: Mineral-based sunscreens are safer than chemical sunscreens.

The reality: Both types are safe to use, but there are fewer unknowns with mineral sunscreens since they are not absorbed into the skin, Lim said.

Chapas said that’s one reason why she prefers mineral sunscreens. She also appreciates their versatility, since they can be applied on top of makeup or moisturizer. “The challenge is that some of these formulations have a whitish cast to them, so you have to find one that works with your complexion,” she said.

Myth 7: You can protect yourself from the sun by building up a “base tan.”

The reality: A tan can provide a small bit of protection, but it’s less than the equivalent of SPF 5, Lim said. That’s not nearly enough to make sunscreen unnecessary.

Besides, a tan itself is a sign of sun damage. “When our skin is exposed to UV light, it stimulates the production of melanin to prevent more UV from entering the skin and damaging the underlying skin cells,” Chapas said. “A tan isn’t healthy. A tan is actually your body trying to protect itself.”

Myth 8: The antioxidant astaxanthin will protect you from UV and act as an “internal sunscreen.”

The reality: There are two ways that antioxidants reduce the biological damage that comes with sun exposure, Lim said. When UVA rays harm DNA, they do so by causing oxidative damage to DNA, and antioxidants can help minimize it. In addition, when visible light interacts with the skin, it can cause cells to produce a type of destructive molecule called reactive oxygen species. Antioxidants can help counteract this process as well.

Including antioxidants in a sun protection regime makes sense, but they can’t do the job by themselves. “There are no pills that act as effectively as a sunscreen,” Chapas said.

If you do want to take an antioxidant to reduce sun damage, astaxanthin isn’t necessarily the best choice, Lim and Chapas agreed. The product Chapas recommends is from Heliocare.

Myth 9: The chemicals in sunscreen get into your bloodstream and build up over time.

The reality: There are no long-term studies of the blood of people who use sunscreen regularly, so there is no data to say whether this is true or false. However, the chemicals are excreted in urine, which is a sign that they don’t linger in the body, Lim said.

People who are wary of chemical sunscreens can opt for mineral sunscreens instead, he said.

Myth 10: You can keep sun damage at bay by wearing a good hat.

The reality: A wide-brimmed hat will definitely help protect you from the sun. This is particularly true for people who are bald or have thinning hair, since “we don’t have great sunscreens for hair-bearing areas,” Chapas said.

However, a hat will only block UV rays coming from above. Without sunscreen, you’ll still be vulnerable to rays that reflect off the water, sand, or urban surfaces like a sidewalk and come at your skin from below. (This is also why you need sunscreen even if you’re in the shade.)

“There are multiple actions we need to take,” Lim said. “Each one of them is helpful, but it’s not as good as when you put everything together.”

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoRead the Ruling by the Virginia Court of Appeals

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoTracking a Single Day at the National Domestic Violence Hotline

-

Fitness1 week ago

Fitness1 week agoWhat's the Least Amount of Exercise I Can Get Away With?

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoSupreme Court upholds law barring domestic abusers from owning guns in major Second Amendment ruling | CNN Politics

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoTrump classified docs judge to weigh alleged 'unlawful' appointment of Special Counsel Jack Smith

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoSupreme Court upholds federal gun ban for those under domestic violence restraining orders

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoNewsom seeks to restrict students' cellphone use in schools: 'Harming the mental health of our youth'

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoTrump VP hopeful proves he can tap into billionaire GOP donors