Science

Could I Survive the ‘Quietest Place on Earth’?

The day of my document try, Orfield crossed the room’s threshold, and his voice instantly sounded far-off, because the wedges absorbed his sound waves. After I adopted him inside, the sound grew to become intimate. I had been warned that anybody talking to me inside an anechoic chamber would sound as in the event that they had been standing simply subsequent to me, murmuring into my ear. It’s an aural phantasm: In a standard room, the one manner for us to listen to speech straight from somebody’s mouth, with no reverberation, is for her or him to speak proper into our ear.

The chamber was outfitted with an workplace chair for my three-hour keep. Orfield Laboratories’ gray-ponytailed supervisor, Michael Position, outlined the difficult phrases I would wish to stick to in an effort to set a brand new document: I would wish to remain within the room for 3 hours. It was my option to have the lights on or off. Confronted with the prospect of looking at a 12-by-10-foot room for 3 hours with no adornments besides a chair and lots of of hanging fiberglass pyramids, I opted for complete darkness. “Typically folks like to put down or sit on the ground, so I go away a pleasant padded blanket in right here,” Position stated, handing me a blue blanket — which I unfold throughout the ground — earlier than shutting the door (unlocked, he assured me), leaving me in lightless silence.

To start out, I laid on my abdomen — a place I felt was relaxed sufficient for my physique to acclimatize to the dearth of stimulation, however uncomfortable sufficient to stop my instantly falling asleep, which might have been a mortifying flip of occasions to clarify to my employer, who anticipated me to offer an in depth written description of my expertise. I resolved to lie on my again and pray the phobia of being fired could be sufficient to maintain me awake at nighttime for 3 hours, regardless of the scientific prognosis of narcolepsy that makes it nearly not possible for me to remain awake in even reasonably cozy semidark situations. (I had not recognized that there could be a blanket within the chamber — my kryptonite.)

As soon as supine, I skilled the distinctive and briefly horrifying sensation that my ears had been touring up very quick in an elevator whereas the remainder of my physique fell gently towards Earth. I had the distinct feeling of my ear canals filling with an in-rushing silence that was someway thicker than the quiet I had first observed within the chamber. Inside seconds, this ceased, and every thing sounded — or somewhat, continued to don’t have any sound — precisely the identical as earlier than. I groped round for the notepad and pen I introduced and recorded the observations that began to roll in: “grey ponytail,” “thick silence.”

However was I recording them? It was not possible to inform within the unrelenting darkish. What if the free lodge pen didn’t work? What if I took reams of attention-grabbing notes over the course of three hours, solely to find, when the lights flickered on, that the pen had been dry and recorded nothing? Why do I, an expert journalist, consistently discover myself counting on free lodge pens throughout essential moments of my assignments? Might I press onerous sufficient with an inkless pen to have the ability to reveal the indentations of my handwriting after the actual fact by rubbing over them with crayon? Wasn’t it simply my luck that the one pen I had introduced was very possible incapable of writing, and that I had idiotically positioned myself underneath situations the place I might be unable to definitively verify this for 3 hours?

In additional summary methods, I had ready somewhat totally for this project, having contacted Dr. Barbara Shinn-Cunningham, the director of the Neuroscience Institute at Carnegie Mellon College, and requested her if turning into conscious of my very own physique sounds would make me go insane. “No,” she stated. “Until you may have a predilection for being insane to start with — which, you already know, may very well be.” That opened up a brand new avenue of inquiry. I referred to as Dr. Oliver Mason, a researcher of psychotic problems on the College of Surrey, who has led research monitoring topics’ experiences in anechoic chambers. “Should you take away all sensory enter,” Mason stated, “our brains, that are at all times making an attempt to tell apart sign from noise anyway, merely see sign the place there objectively isn’t one.” Even when they don’t have any psychological sickness, some individuals are extra vulnerable to conjuring phantom alerts than others and can achieve this way more shortly, in line with Mason. Most individuals tolerate brief intervals of time in lightless anechoic chambers — about 20 minutes, for his experiments — “tremendous.” People vulnerable to “uncommon perceptual experiences” — who suppose issues are taking place to them once they’re not — typically report experiencing hallucinations inside that small window.

Science

Will personal firefighting devices help or hurt in future wildfires?

Patrick Golling yanked the pull cord, and the Honda engine roared to life. Seconds after it began sucking water out of his father’s pool, a powerful stream erupted from an agricultural irrigation nozzle fixed atop a bright red pole a few feet away, connected with a fire hose.

In a minute flat, the system meticulously jerked across the landscape, drenching the ravine in 50 gallons of water. The demonstration on a hot July afternoon left the blackened sticks below the property — once trees before the Palisades fire ripped through — dripping with chlorinated water.

The contraption is the brainchild of Golling and Arizona engineer Tony Robinson. After a TV interview where Golling discussed a cobbled-together version of the tech that he says saved his father’s home from the Palisades fire, Robinson cold-called him, and Realize Safety was born.

Now, the two talk of ambitious visions where entire neighborhoods living amid California’s rugged brush-covered landscapes band together to create a community defense network of automated firefighters.

Realize Safety’s defenders use an agricultural irrigation nozzle to spray 50 gallons of water per minute on surrounding vegetation.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

Their system is the latest entrant in a growing group of often-expensive, high-tech sprinkler systems designed to protect homes in high fire hazard areas. But while a blue-ribbon commission after the January fires recommended L.A. adopt exterior sprinkler technology, some fire officials warn there’s limited evidence that these elaborate and flashy systems work.

Instead, they say the systems distract from less-glamorous but proven measures to protect homes, such as brush clearance and multipaned windows, while encouraging residents to risk their lives by staying back during an evacuation to protect their homes.

“Good solutions don’t pop up overnight,” said David Barrett, executive director of the Los Angeles Regional Fire Safe Council. “There is no silver bullet.”

Especially for a vicious blaze such as the Palisades fire. Given the extreme weather conditions — winds over 80 mph, incredibly dry vegetation — there was very little firefighters, let alone home defense systems, could do, Barrett said.

“It doesn’t matter what you’ve got in your pool,” he said. “Nothing is going to stop an urban wildfire from progressing if it’s wind-driven — sorry. That’s the end.”

Asked whether the system saved his father’s home, Golling did not mince words: “Absolutely.”

Patrick Golling of Realize Safety adjusts the nozzle on one of the company’s defenders.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

After Golling got word of a fire developing in the Palisades on Jan. 7, he immediately thought of the gas pump and irrigation sprinkler system his father had bought just months before to protect his home in the Palisades Highlands. Golling rushed to his father’s house and spent the next two days deploying the system throughout the neighborhood, putting out spot fires that threatened the development. Golling said firefighters encouraged him to keep up the work as they struggled to contain monster blazes one neighborhood over.

As the smoke settled, most of Golling’s neighborhood remained standing.

But little data exist on the effectiveness of home defense sprinklers.

Wildfire researchers often use large datasets of destroyed and standing homes after devastating fires to compare the success of the various home hardening strategies they used. But scientists have yet to identify and analyze fires where sprinkler systems were widely used.

Some anecdotal evidence has suggested that these systems provide some protection. An analysis of the 2007 Ham Lake fire in Minnesota found that of 47 homes identified with functioning sprinkler systems, all but one survived. Meanwhile, only about 40% of the 48 homes without the systems remained standing after the fire.

Typical home defense sprinkler systems work by drawing water from utility systems, and using it to wet the exterior of a house and create — at least theoretically — another barrier from fire. Realize Safety’s goal is to prevent the fire from even reaching the house by dousing nearby vegetation in water and creating a mist to dampen any embers that could ignite the home. To do it, they’re tapping into an underutilized source of water: pools.

Barrett said that, without a doubt, firefighters could put pool water to better use than these systems. Firefighters, he said, already have all the equipment they need to utilize pool water, and all residents have to do is install a clear sign out front letting firefighters know they have a pool.

But as Golling looked at the view of the Palisades from his father’s backyard in early July, he counted eight destroyed homes with still-full pools.

“We think — that had they had a system in place like the one we’re talking about — they could have saved their homes,” Golling said.

Utility water sources are not designed to handle large-scale urban fires. During the Palisades fire, the chief engineer for the city’s water utility told The Times that the system saw four times the normal water demand for 15 hours straight.

It’s in part why, when an independent 20-member Blue Ribbon Commission on Climate Action and Fire-Safe Recovery recently issued dozens of recommendations for rebuilding and recovery, it called for prioritizing additional water storage capacity in neighborhoods and encouraging the development of standards for and the installation of systems that draw on water stored in pools or cisterns, with external sprinklers to douse homes.

Using a 20,000-gallon pool, Realize Safety’s system can run for over six hours straight. And unlike many traditional water defense sprinklers, it is not dependent on the house having electricity and access to utility water systems.

Reliability is paramount for Robinson, who has spent much of his engineering career working on airplanes and satellites — where failure is synonymous with catastrophe.

The same is true for wildfire defense. In the Ham Lake fire, the researchers also counted nine residences where home defense sprinklers failed. Eight of them burned.

Realize Safety’s system pulls water from residential pools, a widely untapped source of water during urban fires.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

In the quest for reliability, Golling and Robinson have made significant improvements on the unwieldy system Golling used in January (where, after some time, the generator cart rattled itself straight into the pool it was drawing water from). With a sturdy generator cart and sprinklers that are firmly anchored into the ground, the two are confident that residents can trust it long after they’ve evacuated.

But Barrett credits success stories such as Golling’s not to specific technology, but instead to the dangerous practice of ignoring an evacuation order to protect a house. He worries systems such as Realize Safety’s — that essentially give residents all the tools they need to try their hand at firefighting instead of evacuating — could encourage more people to stay behind, as Golling did.

“The problem with that is people then stay behind putting their lives and the lives of firefighters at risk, when they’re not trained in firefighting,” he said.

A comprehensive 2019 study from fire researcher Alexandra Syphard found that, in previous Southern California wildfires, a civilian staying behind to protect a house reduced the chance of a home burning by 32% — more than every other factor studied, including defensible space, concrete roofs and even the presence of the fire department at the property. (The study did not evaluate the effectiveness of sprinkler systems, which were not widely used in the fires analyzed.)

However, fire officials across the state — in no unclear terms — strongly discourage this practice. It endangers human life, and when a manageable fire fight suddenly becomes unmanageable for a homeowner, rescue efforts can redirect essential resources that are desperately needed elsewhere.

Some fire safety advocates also worry flashy and unproven tech could distract from well-tested home-hardening methods, such as clearing flammable debris from the yard and roof.

Barrett recalled visiting a house about a year ago to inspect the resident’s home-hardening efforts and provide feedback.

“The person had spent $50,000 on a sprinkler system, but he had overgrown branches hanging onto his roof and the rain gutters were all full of needles,” he said. Barrett’s blunt personal assessment: “This house is going to burn down.”

“Chopping those branches and clearing the needles out would have cost $1,000 or less,” he said.

Golling and Robinson say they’re focused on providing the cheapest, most reliable tech they can. They see their home defenders as another, relatively affordable, tool in the arsenal to increase the odds their customers’ homes survive a fire.

A fully operational, autonomous system starts at $3,450, which Golling said is cheaper than what he spends on defensible-space lawn maintenance in some years.

“We did the brush clearance. We have the water pump. We’re going to do the ember-resistant vents and home hardening,” Golling said. “You’ve got to really do it all.”

Times staff writer Ian James contributed to this report.

Science

National suicide prevention hotline plans to stop offering LGBTQ+ youth counseling. Queer advocates in L.A. wonder what's next

Amy Kane was filled with dread when she heard that the national suicide prevention lifeline would stop offering specialized crisis intervention to young LGBTQ+ Americans and end its partnership with the West Hollywood-based Trevor Project.

With the service set to end July 17, Kane, a therapist who identifies as lesbian, believes the Trump administration is sending a clear message to queer Americans: “We don’t care whether you live or die.”

Since it launched in 2022, more than 1.3 million queer young Americans struggling with a mental health crisis have dialed the 988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline, which gave them the option to press “3” to connect with a specialist trained to address their unique life experiences. As the largest of seven LGBTQ+ contractors, the Trevor Project alone handles about half of all volume from queer callers to the 988 line.

The government’s decision is yet another broadside from an administration whose actions have left queer public health advocates and providers reeling, including at the Los Angeles LGBTQ Center, where Kane serves as director of mental health services.

Under pressure from the Trump administration, Children’s Hospital Los Angeles sent letters to families in early June saying it planned to suspend its healthcare program for transgender children and young adults in late July. The LGBTQ Center and other groups have demanded that the hospital reconsider.

Around the same time came the news about the 988 line and the Trevor Project, a nonprofit founded in 1998 by the makers of the Academy Award-winning short film “Trevor” — about a teen who attempts suicide — to address the absence of a major prevention network tailored to the needs of queer youth.

“So much has been thrown our way in the last five months,” Kane said. “It’s across the board. It’s not just mental health. We see what’s happening with gender-affirming care, dramatic cuts in research for HIV and STIs. … What’s next?”

Given L.A.’s status as a haven for LGBTQ+ people — the first permitted Pride parade took place in Hollywood in 1970 — Kane wonders whether the recent moves are an attempt to intimidate and punish Californians for being so welcoming.

Terra Russell-Slavin, left, denounced cuts to LGBT health funding as public health care becoming political as Rep. Laura Friedman, center, and Craig Thompson, CEO of the David Geffen Health Center look on at the APLA Health, Michael Gottlieb Health Center in West Hollywood last month.

(Myung J. Chun / Los Angeles Times)

The threats aren’t just coming from Washington. Kane said that she and other leaders had to lobby state legislators recently to preserve funding for a queer women’s preventive-healthcare program offered through the L.A. LGBTQ Center that was to be revoked due to a state budget shortfall. For now, the program has been given a temporary reprieve.

“It used to be this idea of, ‘Oh yeah, that’s in the red states, but I’m safe in California’ — it doesn’t feel that way anymore,” Kane said.

Staff members at the Trevor Project are scrambling to figure out how to save the jobs of about 200 counselors who are paid through the federal contract, including raising private funds to make up for the unexpected shortfall, said Mark Henson, interim vice president of advocacy and government affairs. The news couldn’t come at a worse time, given that calls nationwide are on pace to top 700,000 in 2025. That’s up from 600,000 in 2024, a spokesperson said, citing metrics from the U.S. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

Another 100 crisis counselors are employed and paid separately by the Trevor Project itself. They will continue taking calls through the project’s own 24/7, free crisis line, one of several options that local LGBTQ+ organizations offer. Los Angeles County’s Alternative Crisis Response has a 24/7 helpline at (800) 854-7771 that also provides culturally sensitive support services.

But Alex Boyd, the Trevor Project’s director of crisis intervention, said he isn’t sure how his organization can make up for the loss of the nationwide visibility and federal support that the 988 partnership affords them.

LGBTQ+ young people are more than four times as likely to attempt suicide than their peers, according to the Trevor Project. Its 2024 survey found that in California, 35% of LGBTQ+ young people seriously considered taking their own lives and that 11% of respondents had attempted suicide in the previous year.

In defending the decision to stop working with the Trevor Project at a House budget hearing in May, Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. said that while Trump supports the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline in general, “We don’t want to isolate different demographics and polarize our country.”

The big question, Boyd said, is will young LGBTQ+ Americans who already feel shunned or misunderstood still trust a suicide prevention line that no longer offers counselors they can easily relate to?

A one-size-fits-all approach doesn’t work when it comes to people in emotional and mental distress, Boyd said.

He fears the worst.

“The fact that such a significant amount of our capacity for impact has now been stripped away — there is no operational way in order to navigate through a moment like this that doesn’t result, in at least the short term, in a loss of life.”

Counselors at the Trevor Project hear the anguish over the anti-LGBTQ+ backlash in the voices of young callers seeking help through the lifeline, Boyd said. “The statements we are hearing are: ‘Our government doesn’t support me. The government is actively erasing my experience from the national conversation.’ ”

“Increasingly, the biggest thread that we see from young people reaching out to us is this idea that it is already difficult to be a young person in the world — this is another layer that we’re adding onto children’s lives,” Boyd said. “They’re coming to us saying they’re not sure how they’re going to be able to navigate through more years of this before they get some level of autonomy and agency and find some sense of safety.”

Along with a host of executive actions signed by the president, thousands of bills targeting the LGBTQ+ community have been introduced in state legislatures, in cities and in school districts in California and around the country, including calls to ban books that mention same-sex relationships and gender identity, remove the Pride flag from government buildings and kick trans athletes off of sports teams.

Adding to the strain on the queer community, Trump’s self-described “Big Beautiful Bill,” recently passed in both houses in Congress, cuts public health funding for low-income Americans who receive Medicaid. LGBTQ+ Americans are twice as likely to rely on Medicaid to receive their health care than other Americans, said Alexandra Curd, a staff policy attorney at the national advocacy group Lambda Legal.

Over 40% of nonelderly U.S. adults living with HIV depend on the federal program for their healthcare needs compared to 15% for the general population, according to KFF. Many recipients rely nonprofit organizations funded by federal grants to get HIV and STI screenings and receive HIV prevention medications such as PREP and PEP, Curd said.

Because of the Medicaid cuts and the prospect of increased difficulty in accessing preventive care and emotional support, “We’re going to possibly be seeing rising infections rates for HIV,” she said.

Curd said a recent spike in HIV rates among Latino men could only worsen. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention officials have cited a lack of adequate funding, racial bias, language barriers and mistrust of the medical system among the reasons that gay and bisexual Latino men account for a disproportionate percentage of new HIV cases.

Lambda Legal’s help desk has already received more requests for assistance with health care, employment and housing discrimination in the first half of 2025 than in all of 2024, with the most pressing need coming from trans and nonbinary callers.

One piece of good news for L.A. came recently when Rep. Laura Friedman (D–West Hollywood) announced that the Trump administration had restored more than $19 million in federal grants for HIV and STI prevention and tracking that were earmarked for the L.A. County Department of Public Health but slashed by the CDC. Friedman said she and others spoke out against the cut were able to secure an extra $338,019 in federal funding for the new fiscal year starting June 1.

But it’s hard for healthcare organizations to celebrate given that vital funds for mental health and HIV programs were targeted in the first place.

Manny Zermeño, a behavioral health specialist at the Long Beach office of another queer community service organization, APLA Health, senses the distress in his clients. “There is fear, sadness and also with those feelings, it’s natural to have some anger and confusion,” Zermeño said.

The L.A.-based nonprofit focuses on providing free and affordable dental, medical, counseling and other services for queer people 18 and over. It was founded in 1982 as AIDS Project Los Angeles. Back then, a small team of volunteers worked a telephone hotline in the closet of the Los Angeles Gay and Lesbians Community Service Center, fielding calls from panicked residents seeking answers about what was then a fatal disease for which there was no treatment.

The organization operated the first dental clinic in the U.S. catering to AIDS patients out of a trailer in West Hollywood. After movie star Rock Hudson announced he had AIDS in 1985, the organization galvanized support among Angelenos by hosting the first-ever AIDS Walk fundraiser at Paramount Studios, according to its website.

Kane and leaders of other community organizations in L.A. said they would rally once again, this time to assist the Trevor Project.

“All of us who have boots on the ground — you’ll literally have to drag us out by our ankles in order to not provide care to our community,” Kane said. “I don’t believe that queer kids will not have access to resources, because we won’t allow it.”

Science

Cyborg jellyfish could help uncover the depths and mysteries of the Pacific Ocean

For years, science fiction has promised a future filled with robots that can swim, crawl and fly like animals. In one research lab at Caltech, what once felt like distant imagination is becoming reality.

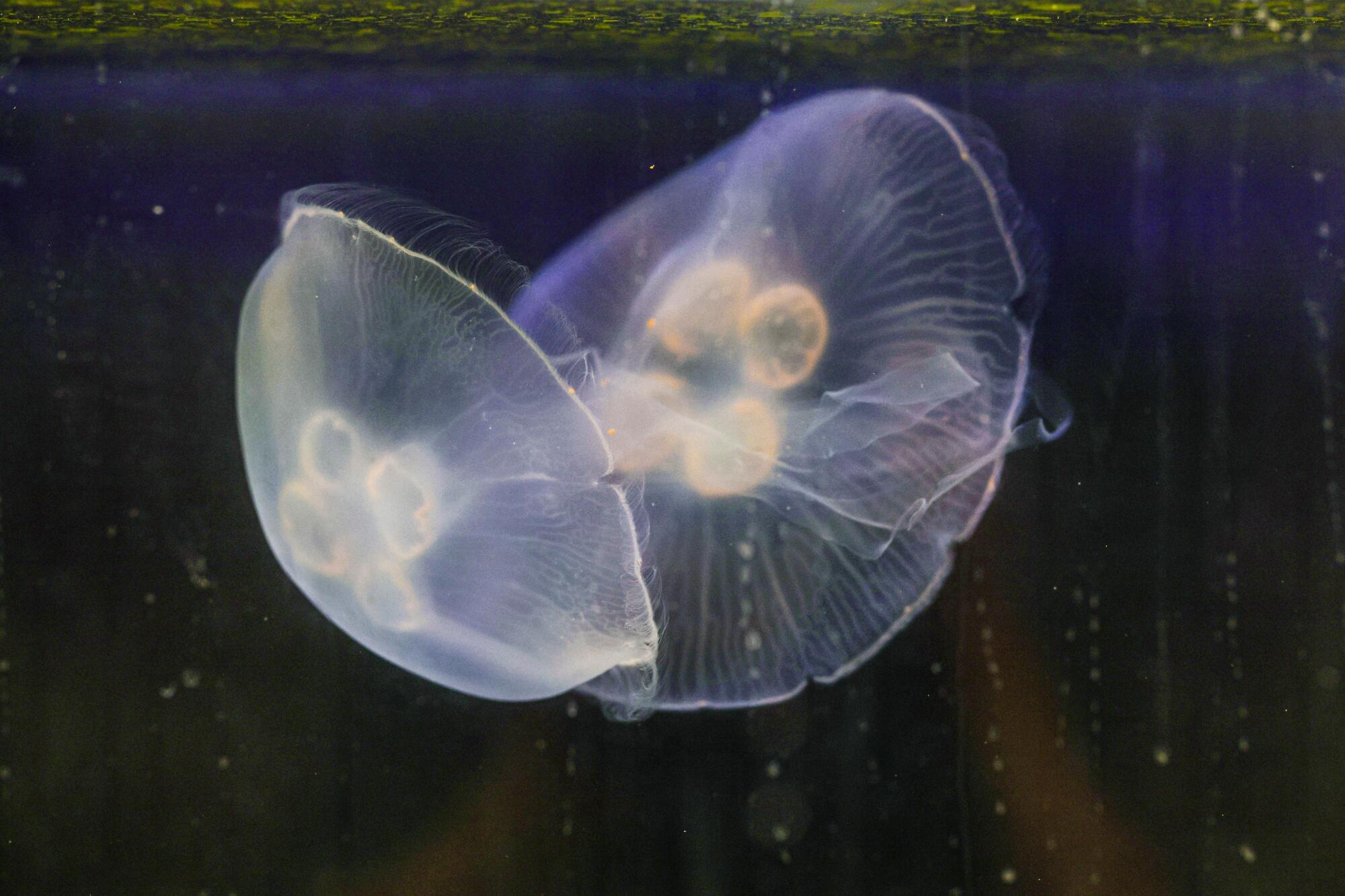

At first glance, they look like any other moon jellyfish — soft-bodied, translucent and ghostlike, as their bell-shaped bodies pulse gently through the water. But look closer, and you’ll spot a tangle of wires, a flash of orange plastic, and a sudden intentional movement.

These are no ordinary jellies. These are cyborgs.

At the Dabiri Lab at Caltech, which focuses on the study of fluid dynamics and bio-inspired engineering, researchers are embedding microelectric controllers into jellyfish, creating “biohybrid” devices. The plan: Dispatch these remotely controlled jellyfish robots to collect environmental data at a fraction of the cost of conventional underwater robots — and potentially redefine how we monitor the ocean.

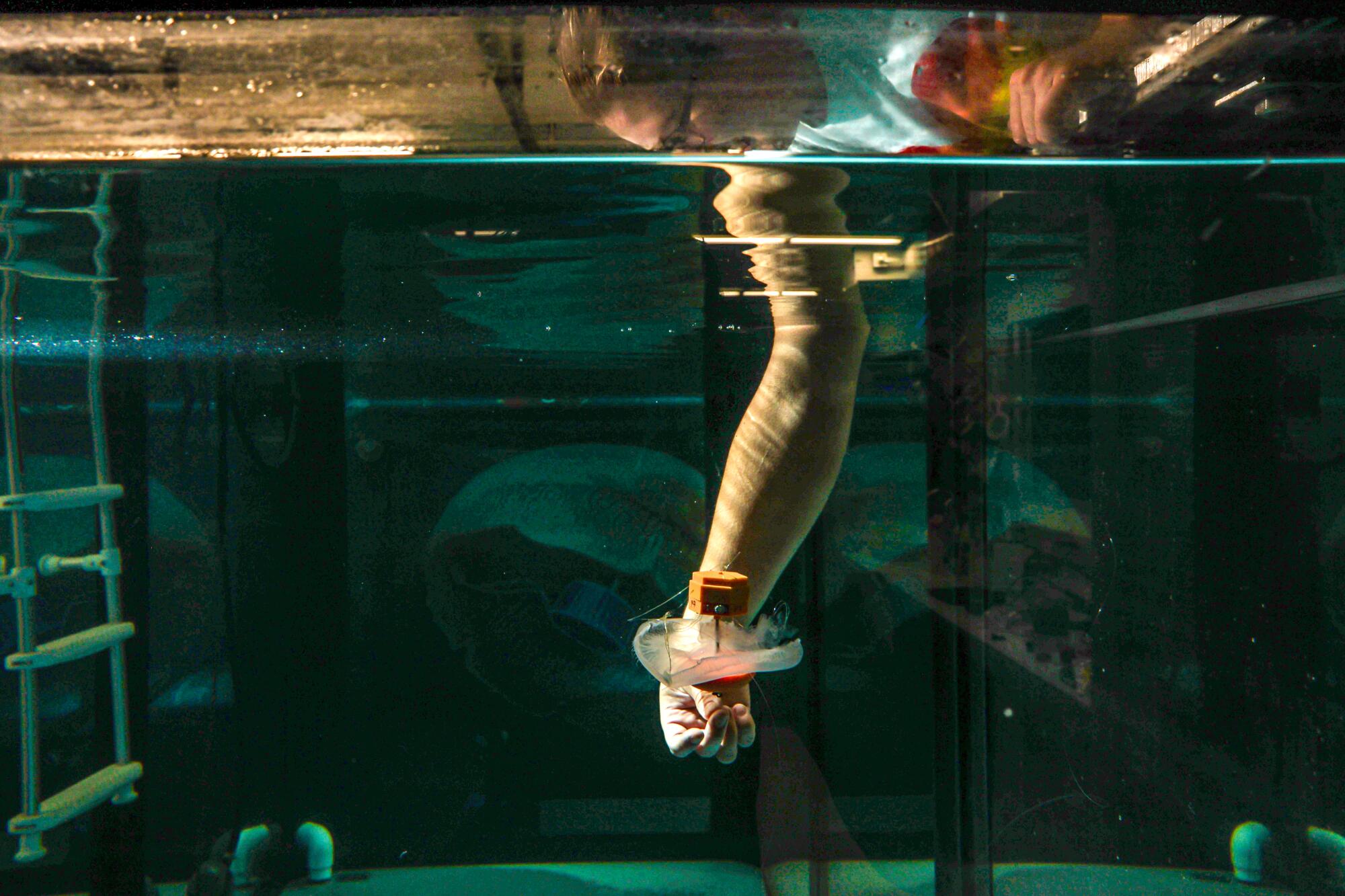

Caltech graduate student, Noa Yoder, a graduate student is one of the members of a team developing cyborg jellyfish, using a device made up of a container filled with sensors and two electrodes that attach to the jellyfish’s muscles.

“It fills the niche between high-tech underwater robots and just attaching sensors to animals, which you have little control over where they go,” said Noa Yoder, a graduate student in the Dabiri Lab. “These devices are very low cost and it would be easy to scale them to a whole swarm of jellyfish, which already exist in nature.”

Jellyfish are perfect for the job in other ways: Unlike most marine animals, jellyfish have no central nervous system and no pain receptors, making them ideal candidates for cybernetic augmentation. They also exhibit remarkable regenerative abilities, capable of regrowing lost body parts and reverting to earlier life stages in response to injury or stress — they can heal in as quickly as 24 hours after the removal of a device.

The project began nearly a decade ago with Nicole Xu, a former graduate student in the Dabiri Lab who is now a professor at the University of Colorado Boulder. Her research has demonstrated that electrodes embedded into jellyfish can reliably trigger muscle contractions, setting the stage for field tests and early demonstrations of the device. Later, another Caltech graduate student, Simon Anuszczyk, showed that adding robotic attachments to jellyfish — sometimes even larger than the jellyfish themselves — did not necessarily impair the animals’ swimming. And in fact, if designed correctly, the attachments can even improve their speed and mobility.

The device allows the scientists to pilot the jellyfish through ocean waters and record measurements of pH, temperature, salinity, etc.

There have been several iterations of the robotic component, but the general concept of each is the same: a central unit which houses the sensors used to collect information, and two electrodes attached via wires. “We attach [the device] and send electric signals to electrodes embedded in the jellyfish,” Yoder explained. “When that signal is sent, the muscle contracts and the jellyfish swims.” By triggering these contractions in a controlled pattern, researchers are able to influence how and when the jellyfish move — allowing them to navigate through the water and collect data in specific locations.

These cyborg devices offer a cheaper (and more sustainable) option for marine research, making it more widely accessible for anyone looking to study the ocean.

The team hopes this project will make ocean research more accessible — not just for elite institutions with multimillion-dollar submersibles, but for smaller labs and conservation groups as well. Because the devices are relatively low-cost and scalable, they could open the door for more frequent, distributed data collection across the globe.

The latest version of the device includes a microcontroller, which sends the signal to stimulate swimming, along with a pressure sensor, a temperature sensor and an SD card to log data. All of which fits inside a watertight 3D-printed structure about the size of a half dollar. A magnet and external ballast keep it neutrally buoyant, allowing the jellyfish to swim freely, and properly oriented.

One limitation of the latest iteration is that the jellyfish can only be controlled to move up and down, as the device is weighted to maintain a fixed vertical orientation, and the system lacks any mechanism to steer horizontally. One of Yoder’s current projects seeks to address this challenge by implementing an internal servo arm, a small motorized lever that shifts the internal weight of the device, enabling directional movement and mid-swim rotations.

Unlike most marine animals, jellyfish have no central nervous system and no pain receptors, making them ideal candidates for cybernetic augmentation.

But perhaps the biggest limitation is the integrity of the device itself. “Jellyfish exist in pretty much every ocean already, at every depth, in every environment,” said Yoder.

To take full advantage of that natural range, however, the technology needs to catch up. While jellyfish can swim under crushing deep-sea pressures of up to 400 bar — approximately the same as having 15 African elephants sit in the palm of your hand — the 3D-printed structures warp at such depths, which can compromise their performance. So, Yoder is working on a deep-sea version using pressurized glass spheres, the same kind used for deep-sea cabling and robotics.

Other current projects include studying the fluid dynamics of the jellyfish itself. “Jellyfish are very efficient swimmers,” Yoder said. “We wanted to see how having these biohybrid attachments affects that.” That could lead to augmentations that make future cyborg jellyfish even more useful for research.

The research team has also begun working with a wider range of jellyfish species, including upside-down Cassiopeia jellies found in the Florida Keys and box jellies native to Kona, Hawaii. The goal is to find native species that can be tapped for regional projects — using local animals minimizes ecological risk.

“This research approaches underwater robotics from a completely different angle,” Yoder said. “I’ve always been interested in biomechanics and robotics, and trying to have robots that imitate wildlife. This project just takes it a step further. Why build a robot that can’t quite capture the natural mechanisms when you can use the animal itself?”

-

Culture1 week ago

Culture1 week agoTry to Match These Snarky Quotations to Their Novels and Stories

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoVideo: Trump Compliments President of Liberia on His ‘Beautiful English’

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoTexas Flooding Map: See How the Floodwaters Rose Along the Guadalupe River

-

Business1 week ago

Companies keep slashing jobs. How worried should workers be about AI replacing them?

-

Finance1 week ago

Do you really save money on Prime Day?

-

Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoApple’s latest AirPods are already on sale for $99 before Prime Day

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoVideo: Clashes After Immigration Raid at California Cannabis Farm

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoJournalist who refused to duck during Trump assassination attempt reflects on Butler rally in new book