Science

A Stinky Stew on Cape Cod: Human Waste and Warming Water

MASHPEE, Mass. — Ashley Okay. Fisher walked to the sting of the boat, pulled on a pair of thick black waders, and jumped into the river to seek for the useless.

She quickly discovered them: the encrusted stays of ribbed mussels, choked in gray-black goo that smelled like rubbish and felt like mayonnaise. The muck on the underside of the Mashpee River will get deeper yearly, suffocating what grows there. It got here as much as Ms. Fisher’s waist. She struggled to free herself and climb again aboard.

“I didn’t assume I used to be going to sink down that far,” mentioned Ms. Fisher, Mashpee’s director of pure sources, laughing. Her officers as soon as needed to yank a stranded resident out of the gunk by tying him to a motorboat and opening the throttle.

The muck is what turns into of the toxic algae that’s taking up extra of Cape Cod’s rivers and bays every summer season.

The algal explosion is fueled by warming waters, mixed with rising ranges of nitrogen that come from the antiquated septic methods that many of the Cape nonetheless makes use of. A inhabitants growth over the previous half-century has meant extra human waste flushed into bogs, which finds its approach into waterways.

Extra waste additionally means extra phosphorous coming into the Cape’s freshwater ponds, the place it feeds cyanobacteria, a kind of algae that may trigger vomiting, diarrhea and liver injury, amongst different well being results. It could actually additionally kill pets.

The outcome:Increasing aquatic useless zones and shrinking shellfish harvests. The collapse of vegetation like eelgrass, a buffer in opposition to worsening storms. Within the ponds, water too harmful to the touch. And a odor that Ms. Fisher characterizes, charitably, as “earthy.”

Collectively, the adjustments threaten the pure options that outline Cape Cod and have made it a cherished vacation spot for generations.

In response, and after a number of lawsuits filed by environmentalists, Massachusetts has proposed requiring Cape communities to repair the issue inside 20 years, by means of a mixture of upgrading the septic tanks utilized by houses that aren’t linked to metropolis sewer methods, and by constructing new networks of public sewer traces.

Native officers say the plan would run into the billions of {dollars} and push housing prices past the technique of many residents.

“It’s bodily, financially and logistically not possible for us to satisfy that commonplace,” Robert Whritenour, city administrator of Yarmouth, one of many largest cities on the Cape, informed state officers throughout a December public listening to in Hyannis. “It’s merely unfair.”

Perceive the Newest Information on Local weather Change

Biodiversity settlement. Delegates from roughly 190 nations assembly in Canada permitted a sweeping United Nations settlement to guard 30 % of the planet’s land and oceans by 2030 and to take a slew of different measures in opposition to biodiversity loss. The settlement comes as biodiversity is declining worldwide at charges by no means seen earlier than in human historical past.

Massachusetts should now determine whether or not to maneuver forward with the mandate, and threat driving some folks from their houses, or weaken the proposed rule, and permit the waters of Cape Cod to degrade even additional. The choice might be a mannequin, or possibly only a warning, for different coastal communities dealing with related predicaments because the local weather warms and overwhelms infrastructure constructed for an earlier age.

“I can barely pay my mortgage,” Paul Haley, a Cape resident who mentioned he lives on a hard and fast revenue, informed state officers on the Hyannis assembly. “If I’ve to place in a brand new septic system, I’ve to depart.”

The price of improvement

Mashpee has about 15,000 full-time residents, no major avenue, and no historic district. What it does have, in abundance, is waterfront.

The city is bounded by Waquoit Bay to the west, Popponesset Bay to the east and Nantucket Sound to the south, speckled by freshwater ponds and sliced by rivers, with marshland and cedar swamps all through. Its title is derived from a Native phrase that means “nice water.”

These waters draw ever extra and ever bigger homes. Mashpee’s most well-known home-owner may be Robert Kraft, proprietor of the New England Patriots, who typically throws events for his workforce at his waterfront residence. “We pulled over Gronkowski for going too quick on his Jet Ski,” Ms. Fisher recounted with a chuckle, referring to the previous Patriots’ tight finish Rob Gronkowski. Neither he nor Mr. Kraft responded to emails despatched to their representatives.

Not removed from Mr. Kraft’s property, Dale Oakley, an official with the Mashpee Wampanoag Tribe, stood close to the purpose the place the Mashpee River enters Popponesset Bay. The Mashpee Wampanoag have lived on Cape Cod for 1000’s of years, and have 170 acres of reservation land throughout the boundaries of Mashpee.

The oysters that develop listed here are a part of the tribe’s weight loss program, heritage and income — the shellfish catch can herald lots of of 1000’s of {dollars} a 12 months.

However the focus of nitrogen within the Mashpee River can attain 3 times the utmost protected threshold established by state officers, in accordance with readings from 2021.

And the typical August water temperature in Popponesset Bay jumped from 68.2 levels Fahrenheit in 2007 to 76.5 levels this 12 months. The primary perpetrator is local weather change, Ms. Fisher mentioned. However she added that the rising muck has additionally created a suggestions loop accelerating that change, as a result of daylight warms the river quicker because it will get shallower.

So the algae have thrived. Their blooms suck up oxygen, suffocating the vegetation round them, after which decompose, layering the riverbed with gunk, killing oysters. The shellfish that survive are smaller, and the realm the place they’ll develop is shrinking.

The shellfish harvest “is a type of financial sustenance,” Mr. Oakley mentioned. “It’s a approach for us to connect with our tradition.”

And it’s steadily slipping away.

‘Swimming Might Trigger Sickness!’

The ecological toll of the Cape’s reliance on septic methods is just not restricted to the shoreline. Cape Cod is dotted with freshwater kettle ponds that had been fashioned by glaciers. One among Mashpee’s largest is Santuit Pond, roughly 170 acres of water surrounded by homes set on hills dotted with beech and scrub pine. In winter, the pond seems to be pristine, a lot the way in which it might need appeared to Henry David Thoreau when he walked the Cape in 1849.

For a lot of the remainder of the 12 months, it’s a foul-odored, neurotoxin-laden, electric-green mess.

“Warning! Closed — no swimming. Swimming might trigger sickness!” reads a steel placard by the boat launch. A close-by signal helpfully instructs determine a poisonous bloom of cyanobacteria, a kind of algae, noting it “can appear like foam, scum, mats, or paint on the floor of the water.”

Lest any would-be swimmers stay tempted to provide it a go, the signage is insistent. “When you see a bloom, keep out of the water and hold your pets out of the water. Don’t fish, swim, boat, or play within the water.”

Andrew McAdams lives on the shore of the pond together with his two stepchildren, 13 and 11. He mentioned he doesn’t have to inform them to keep away from the water. They will see what it seems to be like, which is reminder sufficient.

The pond isn’t toxic on a regular basis, Mr. McAdams mentioned. Solely when it’s heat exterior, which in fact occurs to be the time when his youngsters would most like to make use of it.

The algae blooms in Santuit and different ponds are fueled by phosphorous, which, like nitrogen, is a part in human urine.

If cities like Mashpee put in a sewage system that might acquire waste from houses and clear it at a therapy facility, the quantity of phosphorous and nitrogen coming into the ponds, estuaries and the bay would lower, and the blooms would finally fade.

It might be value the fee, Mr. McAdams mentioned. “You understand how superior it will be to take the children out and go fishing?”

The long run is a effervescent goo.

For native planners in search of a less expensive possibility than sewers, Brian Baumgaertel has a area stuffed with human waste decomposing in tubs that may be of curiosity.

Mr. Baumgaertel is director of the Massachusetts Various Septic System Check Heart, a county group that does just about what its title suggests: He and his employees run sewage by means of quite a lot of contraptions, and see what comes out the opposite finish.

A septic system is, in essence, a field within the floor, which holds no matter is flushed down a bathroom. Stable waste settles on the backside and is bodily sucked out each few years. Liquid waste is distributed into the bottom, the place gravity pulls it by means of the soil, eradicating dangerous micro organism earlier than it reaches the water desk under.

Septic methods work effectively the place houses are too sparse to justify costly sewers and water therapy vegetation. About 95 % of the Cape’s properties use them. However they don’t filter out nitrogen or phosphorus, which seeps into the groundwater and, finally, our bodies of water.

Enter Mr. Baumgaertel’s out of doors laboratory of sewage administration.

On a latest December afternoon, Mr. Baumgaertel eliminated the quilt resulting in an underground chamber. Inside, nitrate-heavy liquid waste flowed into an area full of wooden chips and micro organism. The carbon within the chips gas the micro organism that turns the nitrogen into fuel, a response manifested by small bubbles hissing on the floor of the subterranean goo. The nitrogen fuel is launched into the environment.

Mr. Baumgaertel requested that the effervescent human waste not be photographed; he mentioned the expertise was proprietary.

Who pays?

Nitrogen-capturing septic methods just like the one Mr. Baumgaertel was testing might be an answer for the Cape, a approach to assist restore the waters the place improvement is just not dense sufficient for sewer traces. The draw back: They value about $30,000, greater than twice the price of a fundamental septic system.

And the liquid launched by superior septic methods nonetheless incorporates 5 to eight milligrams of nitrogen per liter — too excessive to be the one resolution for the Cape’s air pollution downside.

The choice is a sewer system and therapy plant, which would cut back the quantity of nitrogen to a few milligrams per liter or much less, low sufficient that many of the bays might get well.

The catch is {that a} sewage system is much more costly.

A couple of miles east of Mr. Baumgaertel’s area of septic innovation, a 55-ton excavator was reducing a concrete manhole right into a freshly dug, 13-foot-deep trench, the place it will be a part of Mashpee’s first main public sewer mission.

When accomplished after two years and at a price of $64 million, the primary section of the sewer system will serve 439 single-family houses, about 5 % of all households in Mashpee. The city’s plan is to finally construct sewers overlaying three-quarters of Mashpee, in accordance with Ray Jack, the city’s wastewater mission supervisor. He guesses it can value as a lot as $450 million.

Mashpee officers had initially deliberate to unfold that building — and the expense — over 25 years. The brand new rule would power them to maneuver quicker.

“What they’re asking is, in my view anyway, an unreasonable timeline,” Mr. Jack mentioned. “These prices are large.”

It’s not but clear who would pay the price of the sewer installations and septic methods upgrades throughout the Cape mandatory to satisfy the water requirements proposed by the state. A number of the cash might come from a tax on trip leases; federal and state cash might cowl a few of the relaxation. However a few of the value is prone to come from residents, both by buying new septic methods or paying greater property taxes.

Christopher Kilian is a lawyer on the Conservation Regulation Basis, a nonprofit that sued the state and Mashpee, arguing that Massachusetts legislation makes it unlawful for cities to permit septic tanks that instantly or not directly launch pollution, together with nitrogen, into floor water. The muse agreed to pause its lawsuit if the state finalized the brand new rule by the center of January.

Mr. Kilian mentioned arguments in regards to the excessive value of cleansing the water are designed to justify inaction, and the precedence ought to be fixing the issue.

“The cities and the state ought to present monetary help in instances of hardship,” he mentioned. “Permitting the air pollution to proceed is just not a sound subsidy that the cities and the state can lawfully present.”

However for all its glittering wealth alongside the shore, median family revenue on the Cape is $82,619 — decrease than the state common. Virtually one-third of the inhabitants is 65 or older.

The Nature Conservancy, an environmental group that has been working with Cape officers to deal with water issues, mentioned the answer must be reasonably priced, or it received’t be replicable elsewhere.

“We do must be actually, actually cautious that we’re not simply making the Cape a spot the place extremely rich folks can go and luxuriate in their clear water,” mentioned Emma Gildesgame, a local weather adaptation scientist with the group. “It’s a extremely laborious query.”

Science

A champion of psychedelics who includes a dose of skepticism

Book Review

Trippy: The Peril and Promise of Medicinal Psychedelics

By Ernesto Londoño

Celadon Books: 320 pages, $29.99

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Ernesto Londoño’s engrossing and unsettling new book, “Trippy: The Peril and Promise of Medicinal Psychedelics,” is part memoir, part work of journalism. It tells of how Londoño sought relief from depression with mind-altering drugs. It also investigates the current fad of “medicinal” psychedelics as a treatment for those struggling with depression, trauma, suicidality and other conditions.

Like other psychedelic enthusiasts, Londoño — a journalist who reported in conflict zones such as Iraq and Afghanistan and served as the New York Times’ Brazil bureau chief — wants us to like psychedelics. They relieve him of depression and suicidality. He then continues to “trip” to engage in self-exploration: escape reality, journey into himself and return with an expanded view of the world.

Calling street drugs and hallucinogenics such as psilocybin, MDMA/ecstasy, LSD and ayahuasca “medicine” is problematic. Psychedelic psychiatry has had a resurgence in the past decade, though only among a minority of medical professionals. Mainstream psychiatry largely abandoned psychedelics by the 1970s, for a variety of reasons.

The renewed interest in psychedelics as a treatment seems to arise more from hope than science — a wish that medicinal psychedelics will be effective because our current treatments are inadequate. Antidepressants known as SSRIs and other approaches are often ineffectual, but that doesn’t mean psychedelics, which can be damaging to many in acute distress, should be tried.

Londoño is more balanced in discussing the benefits and dangers than Michael Pollan and others. Pollan’s bestselling book-turned-Netflix-series “How to Change Your Mind” proselytizes medicinal psychedelics in a way that “Trippy” thankfully doesn’t.

Londoño brings a healthy dose of skepticism. Psychedelics aren’t romanticized with examples of the counterculture movement of the 1960s or hyped by listing celebrities currently using them. The author often questions how much of what he’s part of is “a cult” and if what he’s taking is “voodoo,” not medicine.

Ernesto Londoño, author of “Trippy.”

(Jenn Ackerman)

“Trippy” is a fascinating account of the world of medicinal psychedelics. We attend psychedelic retreats in the Amazon and Latin America. We drink ayahuasca, a syrupy, foul-tasting psychoactive tea that induces vomiting and hallucinations. Ayahuasca calls back “memories” — some real, others false — that participants take as the cause of their emotional ill health.

We visit a ketamine clinic, where Londoño feels a “blissful withdrawal,” retaining “strong powers of perception” but losing “any sense of being a body with limbs that can move at will.”

We watch MDMA (a German pharmaceutical from 1912 now best known as the street drug called ecstasy or molly) being administered at a veterans hospital to treat post-traumatic stress disorder. At a “treatment center”/church/spiritual refuge in Austin, Texas, we witness tobacco being blown into a man’s nostrils, extract from an Amazonian plant squirted into his eyes, and toad venom burned into his forearms under the guise of spiritual salvation.

Unlike the unbridled enthusiasts, Londoño exposes the predatory nature of the psychedelic industry and how it exoticizes the use of hallucinogens as Indigenous medicines. We’re privy to some scandals in this field, specifically sexual abuse and harassment and taking advantage of vulnerable people looking for help.

It’s an engaging memoir of one man’s experiences with psychedelics. Londoño’s little asides, like when he’s talking about meeting the man who would become his husband, endear him to us: “I saw the profile of a handsome man visiting from Minnesota for the weekend. He was a vegetarian and veterinarian. Swoon!”

But as a work of mental health journalism, “Trippy” isn’t, as the book jacket suggests, “the definitive book on psychedelics and mental health today.”

Much is overlooked and left out. Londoño fails to stress that these treatments best serve the “worried well,” those struggling with relatively mild complaints, but can be extremely unsafe for those with serious mental illness, meaning severe dysfunction. Such a person has typically been diagnosed with bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder with suicidality, post-traumatic stress or schizophrenia. They can’t hold a job or live independently, often for years.

Most people Londoño interviews in “Trippy” seek “bliss,” not lifesaving measures to give them a chance at basic functioning. The retreats are less mental health centers than gatherings of spiritual seekers.

Full disclosure: I read “Trippy” with an open mind and as someone who spent 25 years in the American mental health system with serious mental illness. Those years passed the way they do for so many: a string of hospitalizations endured, countless therapeutic modalities tried, numerous mental health professionals seen and myriad psychiatric medications taken (yes, in the double digits).

“Medicinal” psychedelics never came up as a potential treatment. I recovered before fringe psychiatry’s renewed interest in psychedelics became a fad in the past decade.

It’s unsettling that Londoño doesn’t mention the recovery movement and what we know can lead to mental health recovery. He doesn’t mention the five Ps, which are based on the four Ps that Thomas Insel, former head of the National Institute of Mental Health, writes about in “Healing: Our Path from Mental Illness to Mental Health.” To heal, we need people (social support), place (a safe home), purpose (meaning in life), payment (access to mental health care) and physical health (a clean diet and, ironically, no drugs or alcohol).

In this, Londoño fails to explore whether his recovery had as much to do with the changes he made as a result of his first treatment/trip as with psychedelics themselves: changes in diet, renewed purpose, finding love, moving into a new home, leaving his stressful job. If two centuries of psychiatric research has taught us one thing, it’s that there is no magic bullet for mental health recovery.

The book’s most compelling explorations into psychedelics as mental health treatments come when Londoño discusses their use in treating trauma, particularly that which war journalists and veterans experience.

He also explores the pervasiveness of mental health issues and the particular challenges LGBTQ+ people can face.

“Trippy” raises seminal questions we need to be asking as the psychedelic industry reaches further into mental health treatment:

What is “medicine” and what is an illicit drug?

Are we trying to treat those in crisis or simply help anyone escape the suffering that’s part of the human experience?

Should we continue to try more and more extreme treatments?

Or should we finally pay attention to and change systemic issues that are the root cause of so much mental and emotional distress?

Sarah Fay is the author of the bestselling memoirs “Pathological: The True Story of Six Misdiagnoses” and “Cured.”

Science

Maps of Two Cicada Broods, Reunited After 221 Years

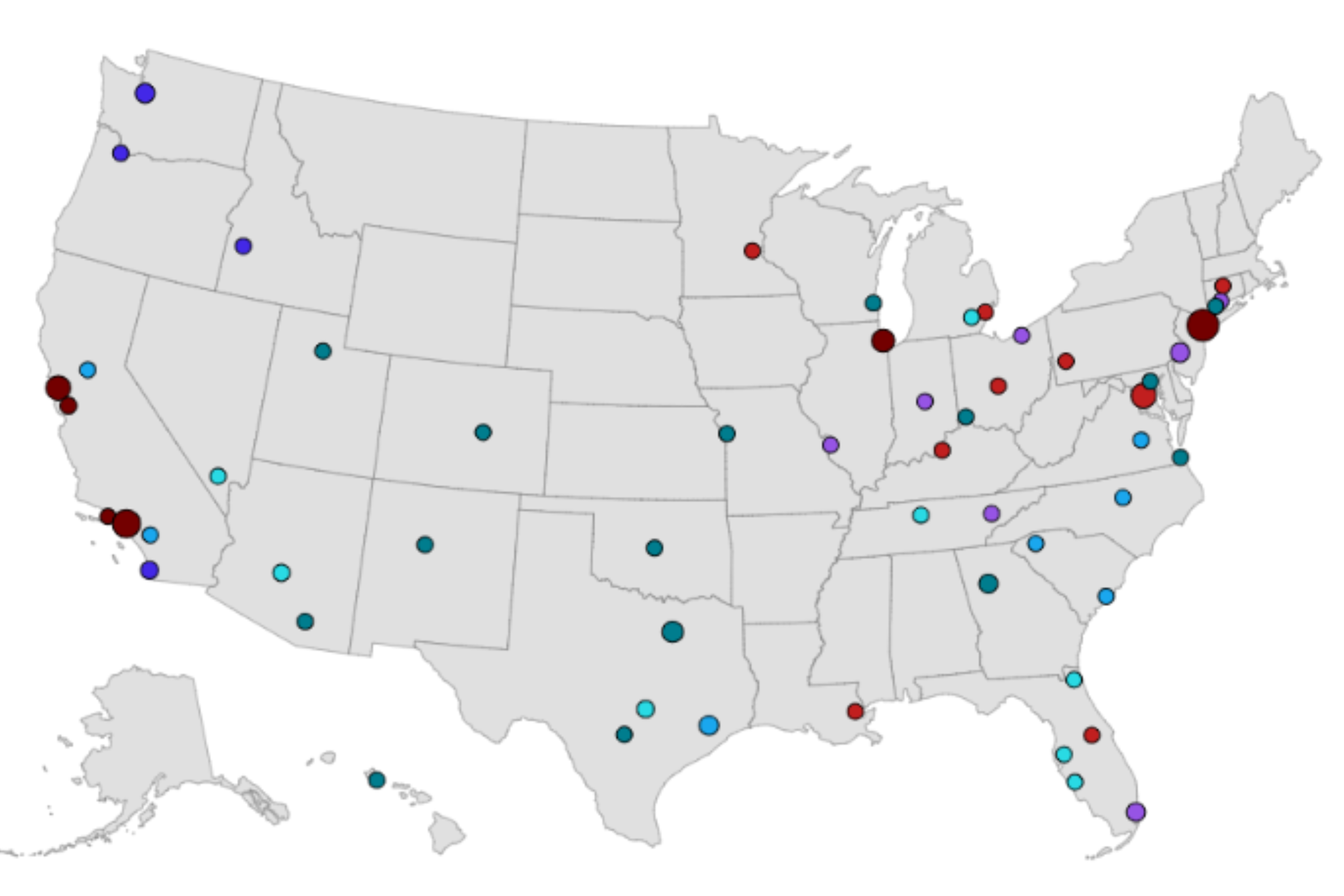

This spring, two broods of cicadas will emerge in the Midwest and the Southeast, in their first dual appearance since 1803.

A cicada lays eggs in an apple twig.

“Insects: Their Ways and Means of Living,” by Robert E. Snodgrass, 1930, via the Biodiversity Heritage Library

Brood XIII, the Northern Illinois Brood, hatched and burrowed into the ground 17 years ago, in 2007.

Brood XIX, the Great Southern Brood, hatched in 2011 and has spent 13 years underground, sipping sap from tree roots.

The entomologist Charles L. Marlatt published a detailed map of Brood XIX, the largest of the 13-year cicada broods, in 1907.

Historic map of cicada emergence.

He also mapped the expected emergence of Brood XIII in 1922.

Historic map of cicada emergence.

This spring the two broods will surface together, and are expected to cover a similar range.

Modern map of cicada emergence.

Up to a trillion cicadas will rise from the warming ground to molt, sing, mate, lay eggs and die.

A Name and a Number

Charles L. Marlatt proposed using Roman numerals to identify the regional groups of 13- and 17-year periodical cicadas, beginning with Brood I in 1893.

A brood can include up to three or four cicada species, all emerging at the same time and singing different songs. Long cicada lifespans of 13 or 17 years spent underground have spawned many theories, and may have evolved to reduce the likelihood of different broods surfacing at the same time.

Large broods might sprawl across a dozen or more states, while a small brood might only span a few counties. Brood VII is the smallest, limited to a small part of New York State and at risk of disappearing.

At least two named broods are thought to have vanished: Brood XXI was last seen in 1870, and Brood XI in 1954.

Not Since the Louisiana Purchase

Brood XIII and Brood XIX will emerge together this year, for the first time in more than two centuries. But only in small patches of Illinois are they likely to come out of the ground in the same place.

In 1786 and 1790, the two broods burrowed into Native lands, divided by the Mississippi River into nominally Spanish territory and the new nation of the United States.

An historic map of the United States from 1783.

Brood XIII entered the ground in 1786, and Brood XIX in 1790. (Expected 2024 ranges are overlaid on the map.)

An historic map of the United States from 1783.

As the ground was warming in April 1803, France sold the rights to the territory of Louisiana, which it acquired from Spain in 1800, to the United States for $15 million.

An historic map of the United States from 1801. That spring, Brood XIII and Brood XIX emerged together into a newly enlarged United States.

An historic map of the United States from 1803.

Their descendants — 13 and 17 generations later — are now poised to return, and will not sing together again until 2245. An historic map of the United States from 1868.

A ‘Great Visitation’

After an emergence of Brood X cicadas in 1919, the naturalist Harry A. Allard wrote:

Although the incessant concerts of the periodical cicadas persisting from morning until night became almost disquieting at times, I felt a positive sadness when I realized that the great visitation was over, and there was silence in the world again, and all were dead that had so recently lived and filled the world with noise and movement.

It was almost a painful silence, and I could not but feel that I had lived to witness one of the great events of existence, comparable to the occurrence of a notable eclipse or the invasion of a great comet.

Then again the event marked a definite period in my life, and I could not but wonder how changed would be my surroundings, my experiences, my attitude toward life, should I live to see them occur again seventeen years later.

The transformation of a cicada nymph (1), into an adult (10).

“The Periodical Cicada,” by Charles L. Marlatt, 1907, via the Biodiversity Heritage Library

Science

What are the blue blobs washing up on SoCal beaches? Welcome to Velella velella Valhalla

The corpses are washing up by the thousands on Southern California’s beaches: a transparent ringed oval like a giant thumbprint 2 to 3 inches long, with a sail-like fin running diagonally down the length of the body.

Those only recently stranded from the sea still have their rich, cobalt-blue color, a pigment that provides both camouflage and protection from the sun’s UV rays during their life on the open ocean.

Aggressive and impactful reporting on climate change, the environment, health and science.

These intriguing creatures are Velella velella, known also as by-the-wind sailors or, in marine biology circles, “the zooplankton so nice they named it twice,” said Anya Stajner, a biological oceanography PhD student at UC San Diego’s Scripps Institution of Oceanography.

A jellyfish relative that spends the vast majority of its life on the surface of the open sea, velella move at the mercy of the wind, drifting over the ocean with no means of locomotion other than the sails atop their bodies. They tend to wash up on the U.S. West Coast in the spring, when wind conditions beach them onshore.

Springtime velella sightings documented on community science platforms like iNaturalist spiked both this year and last, though scientists say it’s too early to know if this indicates a rise in the animal’s actual numbers.

Velella are an elusive species whose vast habitat and unusual life cycle make them difficult to study. Though they were documented for the first time in 1758, we still don’t know exactly what their range is or how long they live.

These beaching events confront us with a little-understood but essential facet of marine ecology — and may become more common as the oceans warm.

“Zooplankton” — the tiny creatures at the base of the marine food chain — “are sort of this invisible group of animals in the ocean,” Stajner said. “Nobody really knows anything about them. No one really cares about them. But then during these mass Velella velella strandings, all of a sudden there’s this link to this hidden part of the ocean that most of us don’t get to experience.”

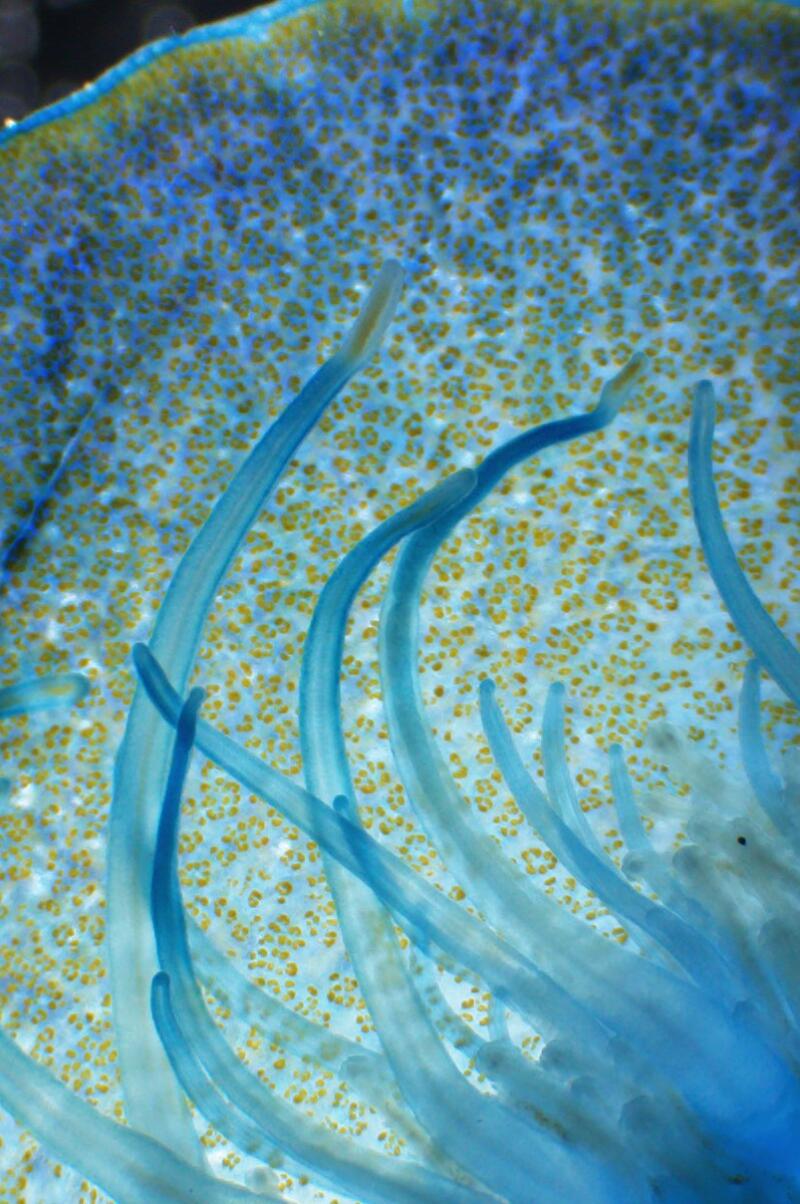

What looks like an individual Velella velella is actually a colony of teeny multicellular animals, or zooids, each with their own function, that come together to make a single organism. They’re carnivorous creatures that use stinging tentacles hanging below the surface to catch prey such as copepods, fish eggs, larval fish and smaller plankton.

Unlike their fellow hydrozoa, the Portuguese man o’ war, the toxin in their tentacles isn’t strong enough to injure humans. Nevertheless, “I wouldn’t encourage anyone to touch their mouth or their eyes after they pick one up on the beach,” said Nate Jaros, senior director of fishes and invertebrates at the Aquarium of the Pacific in Long Beach.

Velella that end their lives on California beaches typically have sails that run diagonally from left to right along the length of their bodies, an orientation that catches the onshore winds heading in this direction. As the organism’s carcass dries in the sun and the soft tissues decay, the blue color disappears, leaving the transparent chitinous float behind.

“The wind really just brings them to our doorstep in the right conditions,” Jaros said. “But they’re designed as open ocean animals. They’re not designed to interact with the shoreline, which is usually why they meet their demise when they come into contact with the shore.”

1

2

3

1. Anya Stajner put Velella velella under a microscope. 2. Magnified, you can see more than blue in the organism. “That green and brown coloration comes from their algae symbionts,” Stajner said. 3. Notice the tentacles too. (Anya Stajner)

Velella show up en masse when two key factors coincide, Stajner said: an upwelling of food-rich, colder water from deeper in the ocean, followed by shoreward winds and currents that direct the colonies to beaches.

A 2021 paper from researchers at the University of Washington found a third variable that appears to correlate with more velella sightings: unusually high sea surface temperatures.

After looking at data over a 20-year period, the researchers found that warmer-than-average winter sea surface temperatures followed by onshore winds tended to correlate with higher numbers of velella strandings the following spring, from Washington to Northern California.

“The spring transition toward slightly more onshore winds happens every year, but the warmer winter conditions are episodic,” said co-author Julia K. Parrish, a University of Washington biologist who runs the Coastal Observation and Seabird Survey Team community science project.

Given that sea surface temperatures have been consistently above the historical average every day since March 2023, the current velella bloom is consistent with those findings.

Previous research has found that gelatinous zooplankton like velella and their fellow jellyfish thrive in warmer waters, portending an era some scientists have referred to as the “rise of slime.”

Other winners of a slimy new epoch would be ocean sunfish, a giant bony fish whose individuals can clock in at more than 2,000 pounds and consume jellyfish — and velella — in mass quantities. Ocean sunfish sightings tend to rise when velella observations do, Jaros said.

“The ocean sunfish will actually kind of put their heads out of the water as they eat these. It resembles Pac-Man eating pellets,” he said. (KTLA-TV published a picture of just that this week.)

Though velella blooms are ephemeral, we don’t yet know how long any individual colony lives. The blue seafaring colonies are themselves asexual, though they bud off tiny transparent medusas that are thought to go to the deep sea and reproduce sexually there, Stajner said. The fertilized egg then evolves into a float that returns to the surface and forms another colony.

Anya Stajner, a PhD student at Scripps, collected by-the-wind sailors but was unable to keep them alive in a lab. “Rearing gelatinous organisms is pretty difficult,” she said.

“I was able to actually collect some of those medusae last year during the bloom, but rearing gelatinous organisms is pretty difficult,” Stajner said. The organisms died in the lab.

Stajner left May 1 on an eight-day expedition to sample velella at multiple points along the Santa Lucia Bank and Escarpment in the Channel Islands, with the goal of getting “a better idea of their role in the local ecosystem and trying to understand what these big blooms mean,” she said.

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoFirst cargo ship passes through new channel since Baltimore bridge collapse

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoHaiti Prime Minister Ariel Henry resigns, transitional council takes power

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoSpanish PM Pedro Sanchez suspends public duties to 'reflect'

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoAmerican Airlines passenger alleges discrimination over use of first-class restroom

-

Movie Reviews1 week ago

Movie Reviews1 week agoAbigail Movie Review: When pirouettes turn perilous

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoEU Parliament leaders recall term's highs and lows at last sitting

-

Science1 week ago

Science1 week agoMosquito season is upon us. So why are Southern California officials releasing more of them?

-

Movie Reviews1 week ago

Movie Reviews1 week agoCity Hunter (2024) – Movie Review | Japanese Netflix genre-mix Heaven of Horror