Rhode Island

Who are the Rhode Island Nine? The stories behind the Marines killed in Beirut in 1983

Between the banks of the Providence River and Dyer Street a memorial honors the nine men who died on Oct. 23, 1983, when a Marine barracks in Beirut, Lebanon was bombed.

Dedicated in 2020, the edifice on Providence’s downtown waterfront incorporates the Marines’ faces. Etched into glass, they are illuminated by both sunlight and electric light.

Recently, a What and Why RI reader asked “Who are the Rhode Island Nine?” after walking by the monument.

Based on material from the Providence Journal archives, here’s a look at the group of men that would become known as the Rhode Island Nine.

Sergeant Timothy Giblin

Giblin, 20, of North Providence, had served in Lebanon with his brother Donald Giblin, who did not live in the same barracks and was not injured in the bombing.

The two of them were known as the “Beirut Brothers.” Giblin’s return in a casket accompanied by his surviving brother drew national media attention.

Giblin was one of 11 children raised by his mother, Jeanne Giblin.

He had an administrative role in the barracks. He was married and he had a daughter, Tiffany, who would grow up to have three children of her own.

Both his widow, Valerie, and his brother William Giblin, remain dedicated to preserving not only his legacy but the memory of the eight other Marines who were killed in Beirut.

Cpl. Rick R. Crudale

Crudale, 21, of West Warwick, was a graduate of Coventry High School. He had certifications in welding and auto-body work from the West Bay Vocational Technical School. He had married his high school sweetheart.

About two weeks before the bombing, a portrait of just Crudale was published on the cover of Time Magazine. He stood among sandbags near a Jeep with a vista of Lebanese buildings in the distance.

The headline above the picture was “Holding the Line.”

Crudale’s family bought every copy of the magazine they could find.

It was a lot of prominence for Crudale. His wife, Heidi, would later say that her husband was a private person.

Cpl. Edward S. Iacovino Jr.

Iacovino, 20, of Warwick, had found a rhythm in the Marines after dropping out of Pilgrim High School during his senior year and later earned his high school diploma while in the military.

Iacovino’s first tour of duty was nearly over but he had just reenlisted due to a discouraging job market.

“In his last letter, he said he’d try staying another year and maybe things would get better,” his mother Elizabeth Iacovino told a reporter as she and her husband awaited official word on their son’s death.

Pfc. Thomas A. Julian

Julian, 22, was a 1979 graduate of Portsmouth High School.

His funeral was held at St. Mary’s Church. He had been a regular there growing up and the pastor recalled that “he always had big bright eyes.”

He had been in the Marines for about a year and was due home the following month. His parents had been planning a big Christmas reunion.

Julian had opted for the Marine Corps as a way of doing “something with his life” after he had some difficulty finding a good job after high school, his mother said.

Julian was a Life Scout in the Boy Scouts. He had also mowed the lawn on the property of the Portsmouth Historical Society, which later became the home of the Portsmouth Beirut Marine Memorial, which honors Julian and members of the Rhode Island Nine.

Cpl. David C. Massa

Massa had tried to quit Warren High School before he graduated in 1981. At the time, the 16-year-old felt he needed to help support his family. He had eight siblings.

A guidance counselor, Marie Boyle, later told a Journal reporter that she had found Massa a job at a textile mill and arranged his classes so he could study mornings and work afternoons. He graduated with good grades and joined the Marines with plans to go to college after his enlistment.

For most of the deployment in Lebanon, he had seemed in good spirits, according to his sister, Anna Cruz, who spoke to a reporter after his death.

However, her brother’s most recent letter lacked the same upbeat tone, she said, adding that he had conveyed that a lot of things were going on in Beirut that he could not write home about.

He urged her not to worry about it and declared he could take care of himself.

Cpl. Thomas A. Shipp

Shipp, 27, of Woonsocket, was the oldest and most experienced of the young men killed in the bombing.

He was a Coast Guard veteran. In June 1977, Shipp and other guardsmen were treated for minor injuries after they tried to help the crew of a burning sailboat.

After six years in the Coast Guard, Shipp drove trucks for a year. Then, he decided to enlist in the Marines.

Cpl. James F. Silvia

Silvia, 20, was a 1981 graduate of Middletown High School.

He was also a cook in the military.

He planned to enter culinary arts school after his discharge.

His death was a double blow for his sister, Lynne.

The bombing took her brother’s life and it also killed her husband, Cpl. Stephen E. Spencer,

Cpl. Edward Soares Jr.

Soares, 21, of Tiverton, participated in a reserve officers’ corps program in high school.

The 1981 Tiverton High School graduate served as a cook, working in the barracks.

He had planned to propose at Christmastime and to marry the following year.

His girlfriend had attended a Tiverton High School football game as she and Soares’ family waited for confirmation that the missing corporal had died in the bombing.

At the game, spectators observed two minutes of silence for him.

Cpl. Stephen E. Spencer

Spencer, 23, of Portsmouth, was a native of Pensacola, Florida.

His official residence had been in Portsmouth since he had married Lynne Silvia. She was the sister of James Silvia – a comrade in arms – and in death.

Silvia had introduced him to her.

The wedding took place the day before the two Marines shipped out for Lebanon as brothers.

Months later, his wife waited sleeplessly, over a period of days, for word about Spencer’s death.

She wore her husband’s dog tags and a T-shirt he had sent her. It was emblazoned with the word “Lebanon” – written in both English and Arabic.

Rhode Island

RI Lottery Powerball, Numbers Midday winning numbers for March 4, 2026

The Rhode Island Lottery offers multiple draw games for those aiming to win big.

Here’s a look at March 4, 2026, results for each game:

Winning Powerball numbers from March 4 drawing

07-14-42-47-56, Powerball: 06, Power Play: 4

Check Powerball payouts and previous drawings here.

Winning Numbers numbers from March 4 drawing

Midday: 2-7-4-4

Evening: 7-6-0-2

Check Numbers payouts and previous drawings here.

Winning Wild Money numbers from March 4 drawing

08-11-12-18-24, Extra: 15

Check Wild Money payouts and previous drawings here.

Winning Millionaire for Life numbers from March 4 drawing

12-13-36-39-58, Bonus: 03

Check Millionaire for Life payouts and previous drawings here.

Feeling lucky? Explore the latest lottery news & results

Are you a winner? Here’s how to claim your prize

- Prizes less than $600 can be claimed at any Rhode Island Lottery Retailer. Prizes of $600 and above must be claimed at Lottery Headquarters, 1425 Pontiac Ave., Cranston, Rhode Island 02920.

- Mega Millions and Powerball jackpot winners can decide on cash or annuity payment within 60 days after becoming entitled to the prize. The annuitized prize shall be paid in 30 graduated annual installments.

- Winners of the Millionaire for Life top prize of $1,000,000 a year for life and second prize of $100,000 a year for life can decide to collect the prize for a minimum of 20 years or take a lump sum cash payment.

When are the Rhode Island Lottery drawings held?

- Powerball: 10:59 p.m. ET on Monday, Wednesday, and Saturday.

- Mega Millions: 11:00 p.m. ET on Tuesday and Friday.

- Lucky for Life: 10:30 p.m. ET daily.

- Millionaire for Life: 11:15 p.m. ET daily.

- Numbers (Midday): 1:30 p.m. ET daily.

- Numbers (Evening): 7:29 p.m. ET daily.

- Wild Money: 7:29 p.m. ET on Tuesday, Thursday and Saturday.

This results page was generated automatically using information from TinBu and a template written and reviewed by a Rhode Island editor. You can send feedback using this form.

Rhode Island

Ranking Rhode Island’s Most Popular Charity License Plates – Rhode Island Monthly

When it comes to expressing ourselves, Rhode Islanders have elevated license plates to an art form. You might not be able to get a new vanity plate — the state suspended applications in 2021 after a judge ruled a Tesla owner could keep his FKGAS plates — but you can still express your Rhody pride with one of seventeen state-approved charity plates. The program has funded ocean research, thrown parades, saved crumbling lighthouses and even provided meals for residents. About half of the $43.50 surcharge goes to the associated charity, while the other half covers the production cost.

________________________

License plate images courtesy of the Rhode island division of motor vehicles.

Atlantic Shark Institute

Year first approved: 2022

Plates currently on road: 7,007

Total raised: $269,530

________________________

License plate images courtesy of the Rhode island division of motor vehicles.

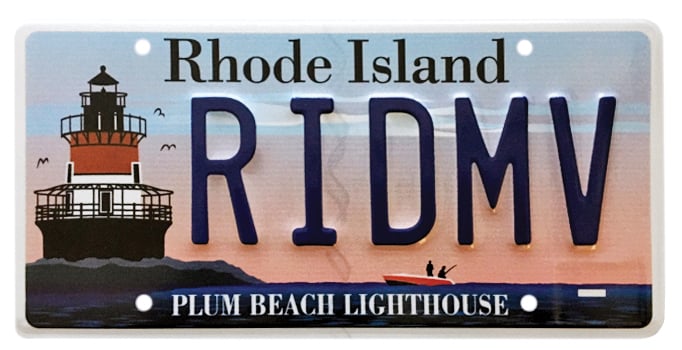

Friends of Plum Beach Lighthouse

Year first approved: 2009

Plates currently on road: 5,024

Total raised: $336,890

________________________

License plate images courtesy of the Rhode island division of motor vehicles.

Wildlife Rehabilitators Association of Rhode Island

Year first approved: 2013

Plates currently on road: 2,102

Funds raised: $32,080

________________________

License plate images courtesy of the Rhode island division of motor vehicles.

Rocky Point Foundation

Year first approved: 2016

Plates currently on road: 1,616

Funds raised: $50,450

________________________

License plate images courtesy of the Rhode island division of motor vehicles.

Rhode Island Community Food Bank

Year first approved: 2002

Plates currently on road: 765

Funds raised since 2021: $11,060*

*Prior to 2021, customers ordered plates directly through the food bank, and total revenue numbers are not available.

________________________

License plate images courtesy of the Rhode island division of motor vehicles.

New England Patriots Charitable Foundation

Year first approved: 2009

Plates currently on road: 1,472

Funds raised: $136,740

________________________

License plate images courtesy of the Rhode island division of motor vehicles.

Audubon Society of Rhode Island and Save the Bay

Year first approved: 2006

Plates currently on road: 1,132

Funds raised: $61,380 for each organization (proceeds split evenly)

________________________

License plate images courtesy of the Rhode island division of motor vehicles.

Boston Bruins Foundation

Year first approved: 2014

Plates currently on road: 1,125

Funds raised: $36,880

________________________

License plate images courtesy of the Rhode island division of motor vehicles.

Beavertail Lighthouse Museum Association

Year first approved: 2023

Plates currently on road: 1,105

Funds raised: $37,610

________________________

License plate images courtesy of the Rhode island division of motor vehicles.

Bristol Fourth of July Committee

Year first approved: 2011

Plates currently on road: 1,104

Funds raised: $17,640

________________________

License plate images courtesy of the Rhode island division of motor vehicles.

Red Sox Foundation

Year first approved: 2011

Plates currently on road: 860

Funds raised: $88,620

________________________

License plate images courtesy of the Rhode island division of motor vehicles.

Gloria Gemma Breast Cancer Resource Foundation

Year first approved: 2012

Plates currently on road: 1,510

Funds raised: $33,360

________________________

License plate images courtesy of the Rhode island division of motor vehicles.

Providence College Angel Fund

Year first approved: 2016

Plates currently on road: 693

Funds raised: $23,220

________________________

License plate images courtesy of the Rhode island division of motor vehicles.

Rose Island Lighthouse and Fort Hamilton Trust

Year first approved: 2022

Plates currently on road: 383

Funds raised: $10,640

________________________

License plate images courtesy of the Rhode island division of motor vehicles.

Friends of Pomham Rocks Lighthouse

Year first approved: 2022

Plates currently on road: 257

Funds raised: $7,580

________________________

License plate images courtesy of the Rhode island division of motor vehicles.

Day of Portugal and Portuguese Heritage in RI Inc.

Year first APPROVED: 2018

Plates currently on road: 132

Funds raised: $3,190

Rhode Island

Rhode Island AG to unveil long-awaited report on Diocese of Providence clergy abuse

PROVIDENCE, R.I. — Rhode Island Attorney General Peter Neronha will release on Wednesday findings from a multiyear investigation into child sexual abuse in the Diocese of Providence.

According to the attorney general’s office, the report will detail the diocese’s handling of clergy abuse over decades.

While the smallest state in the U.S., Rhode Island is home to the country’s largest Catholic population per capita, with nearly 40% of the state identifying as Catholic, according to the Pew Research Center.

Neronha first launched the investigation in 2019, nearly a year after a Pennsylvania grand jury report found more than 1,000 children had been abused by an estimated 300 priests in that state since the 1940s. The 2018 report is considered one of the broadest inquiries into child sexual abuse in U.S. history.

Neronha’s investigation involved entering into an agreement with the Diocese of Providence to gain access to all complaints and allegations of child sexual abuse by clergy dating back to 1950. Neronha’s office said in 2019 that the goal of the report was to determine how the diocese responded to past reports of child sexual abuse, identify any prosecutable cases, and ensure that no credibly accused clergy were in active ministry.

Rhode Island State Police also helped with the investigation.

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoExclusive: DeepSeek withholds latest AI model from US chipmakers including Nvidia, sources say

-

Massachusetts1 week ago

Massachusetts1 week agoMother and daughter injured in Taunton house explosion

-

Wisconsin3 days ago

Wisconsin3 days agoSetting sail on iceboats across a frozen lake in Wisconsin

-

Maryland4 days ago

Maryland4 days agoAM showers Sunday in Maryland

-

Denver, CO1 week ago

Denver, CO1 week ago10 acres charred, 5 injured in Thornton grass fire, evacuation orders lifted

-

Florida4 days ago

Florida4 days agoFlorida man rescued after being stuck in shoulder-deep mud for days

-

Oregon6 days ago

Oregon6 days ago2026 OSAA Oregon Wrestling State Championship Results And Brackets – FloWrestling

-

Massachusetts2 days ago

Massachusetts2 days agoMassachusetts man awaits word from family in Iran after attacks