New York

A Survivor in New York, Cycling With Other Wounded Warriors

Good morning. It’s Tuesday. Today we’ll introduce you to a hero. You may see her riding the streets of New York later this week.

Danielle Green survived her mother’s addiction to crack on the South Side of Chicago in the 1980s. She survived five years playing basketball for the University of Notre Dame, including a year on the bench to heal a torn Achilles’ tendon. As an Army military police officer stationed in Iraq in 2004, she survived a grenade attack that led to the amputation of much of her left arm; back home, she survived the looks of neighbors, who stared openly at her new prosthetic arm, with its pointy metal hook.

This week, Green will ride a bicycle in New York City for the first time. Strangely, she’s a little nervous. She’s used to humidity and heat, living in St. Petersburg, Fla. But she’s not used to hills.

“I don’t know if New York is flat,” said Green, 46. “I don’t know what the humidity will be. It might start raining. And I hope it’s flat.”

Green flies into La Guardia Airport tomorrow. She’ll receive a bike with special handlebars to accommodate her latest prosthetic arm, which grips the bars like an open wrench. On Thursday she’ll participate in the Soldier Ride, an event organized by the Wounded Warrior Project, a nonprofit that helps veterans recovering from physical and emotional traumas.

The ride will start in the heart of the city, on Sixth Avenue, in front of the News Corp. Building, Brooklyn. The cyclists will take the gentle hill of the Brooklyn Bridge, part of a route to Coney Island. They will be surrounded by paramedics and police officers. In some sections, well-wishers will gather, encouraging the cyclists on. There will be street closures, with all the profanity and truck horns such closures always entail.

The middle of the scrum will be mostly quiet. Forty veterans will ride together. If one stops, they all will stop. As the most experienced rider in the group, Green will watch her new friends for signs of physical and emotional distress.

“We start together, we ride together, we finish together,” Green said. “We’re going to ride as a team.”

In a life punctuated by crisis and trauma, Green spent years looking for teams to join. She grew up in the Englewood section of South Chicago, where her mother worked as a bank teller. Then, during the crack epidemic that ravaged the city in the early 1980s, her mother became addicted to the drug.

She lost the bank job, and then their apartment.

“Life got really, really tough,” Green said.

When she was 7, she saw her first Notre Dame football game on television. She loved the gold helmets and NBC’s panning shots of the university basilica’s golden dome. In a family that was falling apart, watching football on Saturday afternoons became Green’s favorite routine, she said. Every broadcast was punctuated by ads for the U.S. Army and Marines.

Green decided: She would join the military. But first, she would attend Notre Dame on a basketball scholarship. She didn’t know that she — a Black girl from a non-Catholic family in a poor neighborhood — might feel out of place at a university that was traditionally composed of white, prosperous young men and didn’t admit women until 1971, seven years before Green was born.

“I started telling people when I was 9 years old that I was going to go to Notre Dame,” she said. “They would just laugh at me.”

Green became a standout left-hander on her high school basketball team, then a scholarship player for Notre Dame.

When she graduated, she became a teacher and basketball coach in a public school in Chicago. Once again, she was lost.

“I went through an identity crisis at about 25,” Green said.

She considered joining the Air Force or an Army intelligence unit, both as an officer. She chose an even harder route: becoming an enlisted member of the military police. Months after 9/11, she joined the army.

“I wasn’t naïve about the fact that we were going to war,” she said.

Then came May 25, 2004. Green’s unit was assigned to a police station in central Baghdad, training officers. On that day, none of the officers showed up. It was Green’s turn to guard the roof, watching the neighborhood for trouble.

The first two rocket-propelled grenades landed in the building two stories below her.

The third landed on the roof.

The blast made Green’s body numb, followed by pain like she had never experienced. She woke up in a hospital bed, disoriented. She couldn’t understand: Why was her left arm now shorter than her right? The commander of her battalion arrived and awarded her a Purple Heart.

After months of recuperation, she returned to Chicago with no community, no purpose.

“I had this hook. People stared,” Green said. “I was about to go into hiding to where people wouldn’t see me. ”

A friend invited Green to a Soldier Ride. It was hard. Her hook slipped off the handlebar, and she didn’t have the abdominal strength to keep herself upright. She fell several times.

The other veterans didn’t stare. They helped. This gave Green an idea.

“Every time I fell down, there was somebody there to pick me up,” she said. “I found my purpose sometime during that first ride, that I am still relevant. I still have something to give back to society.”

Green received two master’s degrees and became a therapist for the Department of Veterans Affairs. She participated in more rides with the Wounded Warrior Project, which also arranged for her to water ski on Lake Michigan and to fish in Alaska. She met President George W. Bush, and Barack Obama, then the junior senator from Illinois. Last year, at a Wounded Warrior Project ride in Washington, D.C., Green got a hug from President Biden.

Asked whether it was a memorable moment, she took a deep breath.

“You know, I’m 46 now,” she said. “I’m not too star-struck anymore. But it was a cool experience.”

This week she’ll fly from Florida to La Guardia and ride a bike 19 miles from Midtown to the ocean.

Green may not enjoy our hills, or our humidity. But New York City does not scare her.

“I’m not worried about the traffic. I’m just worried about not getting hurt, and finishing the ride,” she said. “I always want to finish what I start.”

Weather

Expect a sunny day, with temperatures in the high 80s. The evening will be mostly clear, with temps dropping to the low 70s.

ALTERNATE-SIDE PARKING

In effect until Aug. 15 (Feast of the Assumption).

The latest New York news

METROPOLITAN diary

All dressed up

Dear Diary:

I had recently moved to Manhattan from Mali for law school, from a place where everyone greeted one another to a city where I was searching in vain for connection.

One afternoon, I was on an uptown train in a seat by the door. Across from me sat an elegantly dressed woman and her young daughter.

The girl was wearing a black velvet party dress that was trimmed with white lace, and every blond curl was lying perfectly. Together, the two of them made me feel grubby in my jeans and sweater.

As the mother stared grimly at her phone, the girl wriggled in her seat, her feet dangling. She looked at me. I wrinkled my nose and stuck out the tip of my tongue. She looked away quickly, at her shiny shoes, her mother’s face.

A few moments later, I was urgently seeking her mother’s attention.

“Ma’am? Ma’am! Excuse me!” I said. “Your daughter is licking the subway pole.”

— Julia Barke

Illustrated by Agnes Lee. Send submissions here and read more Metropolitan Diary here.

Glad we could get together here. James Barron returns tomorrow. — C.M.

P.S. Here’s today’s Mini Crossword and Spelling Bee. You can find all our puzzles here.

Melissa Guerrero, Johnna Margalotti and Ed Shanahan contributed to New York Today. You can reach the team at nytoday@nytimes.com.

Sign up here to get this newsletter in your inbox.

New York

Are You Smarter Than a Billionaire?

Over the course of one week, some of the richest people in the world descended on New York’s auction houses to purchase over $1 billion of art. It might have played out a little differently than you would have expected.

Can you guess which of these works sold for more?

Note: Listed sale prices include auction fees.

Image credits: “Untitled,” via Phillips; “Baby Boom,” via Christie’s Images LTD; “Hazy Sun,” With permission of the Renate, Hans & Maria Hofmann Trust/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York; via Christie’s Images LTD; “Petit Matin,” via Christie’s Images LTD; “Concetto spaziale, La fine di Dio,” Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/SIAE, Rome; via Sotheby’s; “Baroque Egg with Bow (Orange/Magenta),” via Sotheby’s; “The Last Supper,” The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc./Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York; via Christie’s Images LTD; “Campbell’s Soup I,” The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc./Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York; via Christie’s Images LTD; “Miss January,” via Christie’s Images LTD; “Fingermalerei – Akt,” via Sotheby’s; “Grande tête mince (Grande tête de Diego),” Succession Alberto Giacometti/Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY; via Sotheby’s; “Tête au long cou,” Succession Alberto Giacometti/ARS, NY/Photos: ADAGP Images/Paris 2025; via Christie’s Images LTD; “Revelacion,” Remedios Varo, Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VEGAP, Madrid; via Christie’s Images LTD; “Le jardin nocturne,” Foundation Paul Delvaux, Sint-Idesbald – ARS/SABAM Belgium; via Christie’s Images LTD.

Produced by Daniel Simmons-Ritchie.

New York

Video: How a Mexican Navy Ship Crashed Into the Brooklyn Bridge

On Saturday, a Mexican Navy ship on a good will tour left a New York City pier bound for Iceland. Four minutes later, it crashed into the Brooklyn Bridge. [Spanish] “It’s falling!” [English] “No way!” Here’s what happened. The Cuauhtémoc had been docked on the Lower East Side of Manhattan for four days, open to visitors looking for a cultural experience. As the ship prepared to leave on Saturday night, a tugboat arrived to escort it out of its pier at 8:20 p.m. The ship’s bow, the front of the vessel, faced Manhattan, meaning it would need to back out of its berth into the East River. As the Cuauhtémoc pulled away from shore, the tugboat appeared to push the side of the ship, helping to pivot the bow south toward its intended route. The river was flowing northeast toward the Brooklyn Bridge and the wind was blowing in roughly the same direction, potentially pushing the ship toward a collision. Photos and videos suggest the tugboat was not tied to the ship, limiting its ability to pull the ship away from the bridge. The Cuauhtémoc began to drift north, back first, up the river. Dr. Salvatore Mercogliano, who’s an adjunct professor at the U.S. Merchant Marine Academy, told The Times that the ship appeared to be giving off a wake. This suggests its propellers may have been running in reverse, pushing it faster toward the bridge. The tugboat sped alongside the ship as it headed north, possibly trying to get in front of it and help the ship maneuver the other way. But it was unable to cut the ship off or reverse its course. All three masts crashed into the underside of the Brooklyn Bridge at approximately 8:24 p.m., four minutes after the ship had left the pier, causing the top sails to collapse. Crew members standing on the masts during the collision were thrown off entirely. Others remained hanging from their harnesses. A New York City patrol boat arrived about eight minutes after the collision, followed quickly by a fire department boat. Additional law enforcement and emergency medical services removed the wounded for treatment. According to the Mexican Navy, two of the 227 people aboard the ship were killed and 22 others were injured.

New York

Audio Data Shows Newark Outage Problems Persisted Longer Than Officials Said

On April 28, controllers at a Philadelphia facility managing air traffic for Newark Liberty International Airport and smaller regional airports in New Jersey suddenly lost radar and radio contact with planes in one of the busiest airspaces in the country.

On Monday, two weeks after the episode, Sean Duffy, the secretary of transportation, said that the radio returned “almost immediately,” while the radar took up to 90 seconds before it was operational.

A Times analysis of flight traffic data and air traffic control feed, however, reveals that controllers were struggling with communication issues for several minutes after transmissions first blacked out.

The episode resulted in multiple air traffic controllers requesting trauma leave, triggering severe flight delays at Newark that have continued for more than two weeks.

Several exchanges between pilots and controllers show how the outage played out.

Outage Begins

Air traffic recordings show that controllers at the Philadelphia facility first lost radio and radar communications for about a minute starting just before 1:27 p.m., after a controller called out to United Flight 1951, inbound from Phoenix.

The pilot of United 1951 replied to the controller’s call, but there was no answer for over a minute.

1:26:41 PM

Controller

OK, United 1951.

1:26:45 PM

Pilot

Go ahead.

1:27:18 PM

Pilot

Do you hear us?

1:27:51 PM

Controller

How do you hear me?

1:27:53 PM

Pilot

I got you loud and clear now.

Two other planes reached out during the same period as United 1951 — a Boeing 777 inbound from Austria and headed to Newark, and a plane whose pilot called out to a controller, “Approach, are you there?” Their calls went unanswered as well.

Radio Resumes, With Unreliable Radar

From 1:27 to 1:28 p.m., radio communications between pilots and controllers resumed. But soon after, a controller was heard telling multiple aircraft about an ongoing radar outage that was preventing controllers from seeing aircraft on their radarscopes.

One of the planes affected by the radar issues was United Flight 674, a commercial passenger jet headed from Charleston to Newark.

1:27:32 PM

Pilot

United 674, approach.

1:27:36 PM

Controller

Radar contact lost, we lost our radar.

1:30:34 PM

Controller

Turn left 30 degrees.

1:31:03 PM

Pilot

All right, we’re on a heading of 356. …

1:31:44 PM

Controller

I see the turn. I think our radar might be a couple seconds behind.

Once the radio started operating again, some controllers switched from directing flights along their planned paths to instead providing contingency flight instructions.

At 1:28 p.m., the pilot of Flight N16NF, a high-end private jet, was called by a controller who said, “radar contact lost.” The pilot was then told to contact a different controller on another radio frequency.

About two and a half minutes later, the new controller, whose radar did appear to be functioning, instructed the pilot to steer towards a location that would be clear of other aircraft in case the radio communications dropped again.

Flight N426CB, a small private jet flying from Florida to New Jersey, was told to call a different radio frequency at Essex County Airport, known as Caldwell Airport, in northern New Jersey for navigational aid. That was in case the controllers in Philadelphia lost radio communications again.

1:27:57 PM

Controller

If for whatever reason, you don’t hear anything from me further, you can expect to enter right downwind and call Caldwell Tower.

1:29:19 PM

Controller

You just continue on towards the field. They’re going to help navigate you in.

This is in case we are losing our frequencies.

1:29:32 PM

Pilot

OK, I’m going over to Caldwell. Talk to you. Have a good afternoon.

Minutes Later, Radar Issues Persist

According to the Federal Aviation Administration, aircraft reappeared on radarscopes within 90 seconds of the outage’s start, but analysis of air traffic control recordings suggest that the radar remained unreliable for at least some radio frequencies for several minutes after the outage began around 1:27 p.m.

At 1:32 p.m., six minutes after the radio went quiet, Flight N824TP, a small private plane, contacted the controller to request clearance to enter “Class B” airspace — the type around the busiest airports in the country. The request was denied, and the pilot was asked to contact a different radio frequency.

1:32:43 PM

Pilot

Do I have Bravo clearance?

1:32:48 PM

Controller

You do not have a Bravo clearance. We lost our radar, and it’s not working correctly. …

If you want a Bravo clearance, you can just call the tower when you get closer.

1:32:59 PM

Pilot

I’ll wait for that frequency from you, OK?

1:33:03 PM

Controller

Look up the tower frequencies, and we don’t have a radar, so I don’t know where you are.

The last flight to land at Newark was at 1:44 p.m., but about half an hour after the outage began, a controller was still reporting communication problems.

“You’ll have to do that on your own navigation. Our radar and radios are unreliable at the moment,” a Philadelphia controller said to a small aircraft flying from Long Island around 1:54 p.m.

Since April 28, there has been an additional radar outage on May 9, which the F.A.A. also characterized as lasting about 90 seconds. Secretary Duffy has proposed a plan to modernize equipment in the coming months, but the shortage of trained staff members is likely to persist into next year.

-

Education1 week ago

Education1 week agoVideo: Opinion | We Study Fascism, and We’re Leaving the U.S.

-

Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoLove, Death, and Robots keeps a good thing going in volume 4

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoAs Harvard Battles Trump, Its President Will Take a 25% Pay Cut

-

Culture1 week ago

Culture1 week agoBook Review: ‘Hunger Like a Thirst,’ by Besha Rodell

-

Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoMeta asks judge to throw out antitrust case mid-trial

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoRepublicans say they're 'out of the loop' on Trump's $400M Qatari plane deal

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoCommissioner Hansen presents plan to cut farming bureaucracy in EU

-

Movie Reviews1 week ago

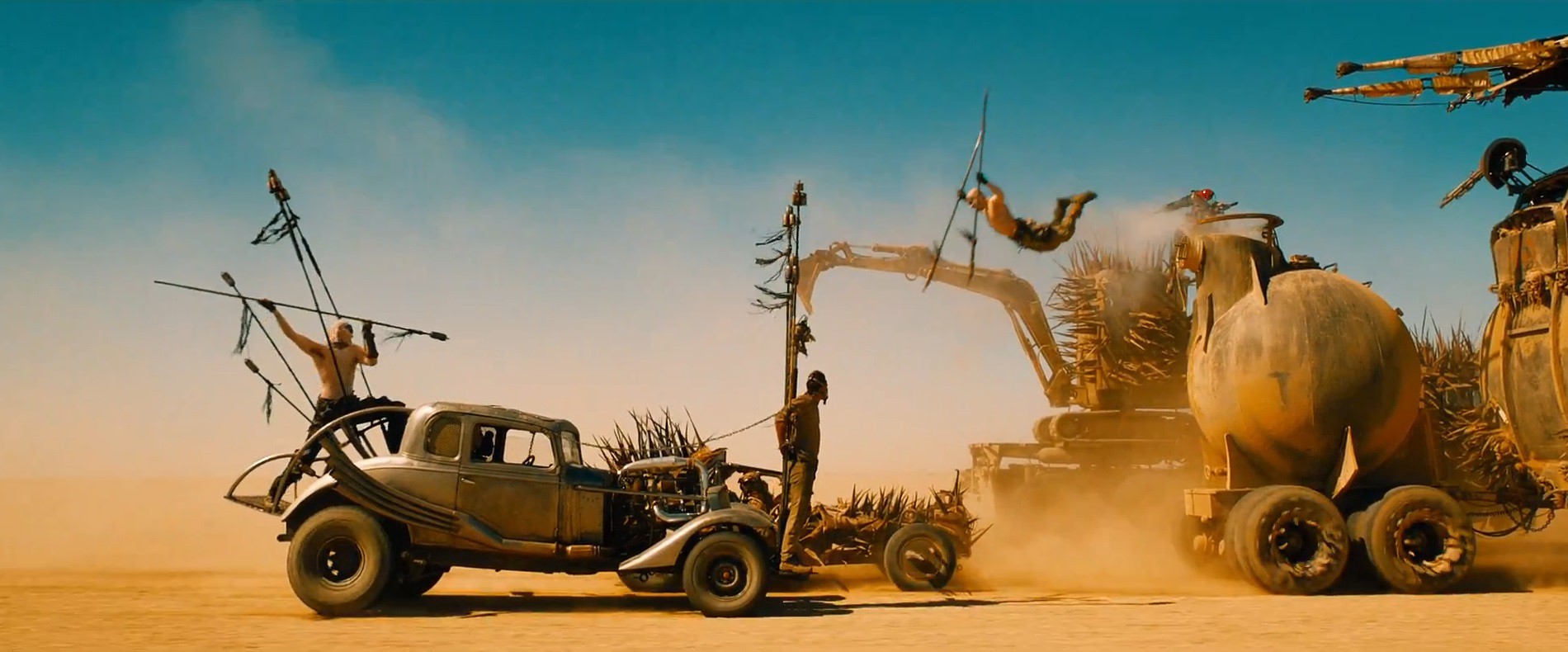

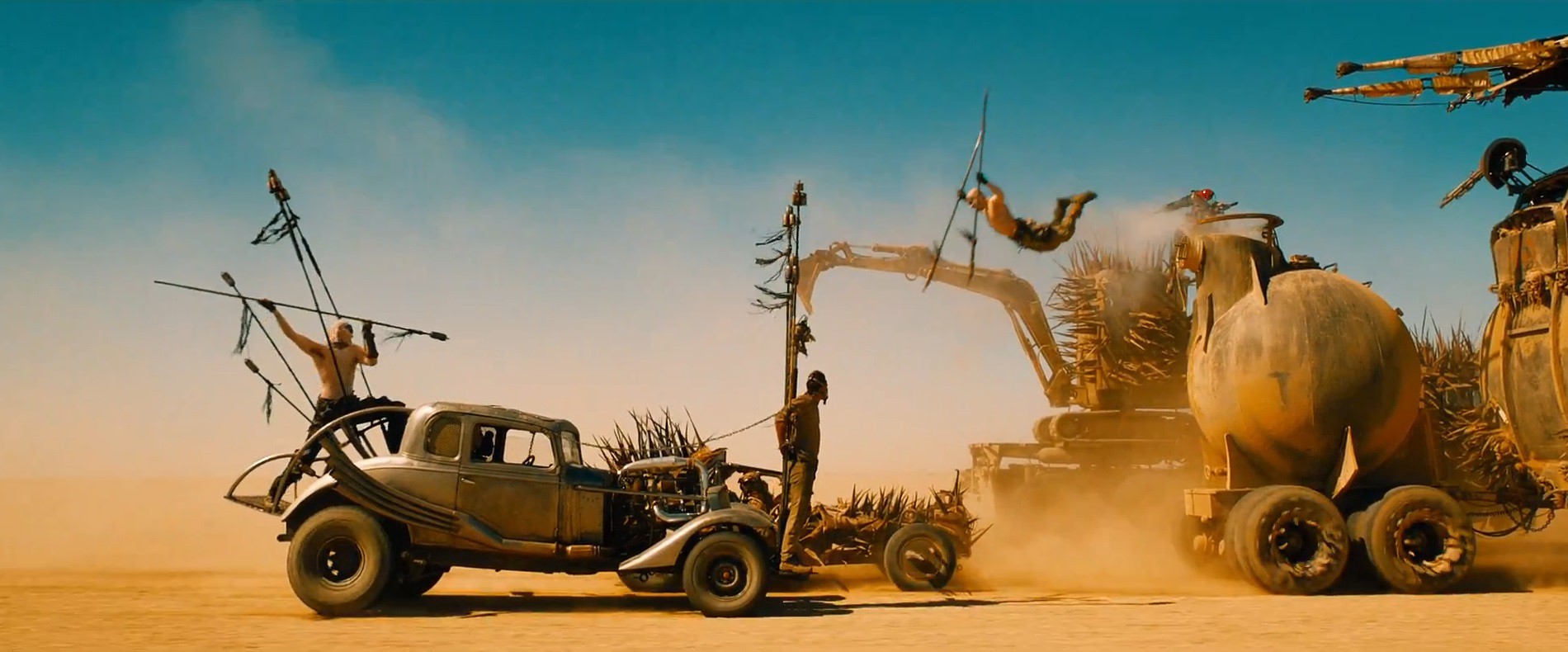

Movie Reviews1 week agoClassic Film Review: ‘Mad Max: Fury Road’ is a Lesson in Redemption | InSession Film