New York

曼哈頓消失的中文路標

和紐約市的許多社區一樣,華埠的歷史也可以看出許多清晰的層次。在曼哈頓下城,共產主義革命前成立的家族公所依然懸掛著中華民國的旗幟。招聘公告欄上貼滿了小紙片,都是面向新移民的。網紅甜品店為年輕的當地人和遊客提供服務。寫有「For Lease / 出租」字樣的標牌無處不在,暗示著華人企業和居民的流失。

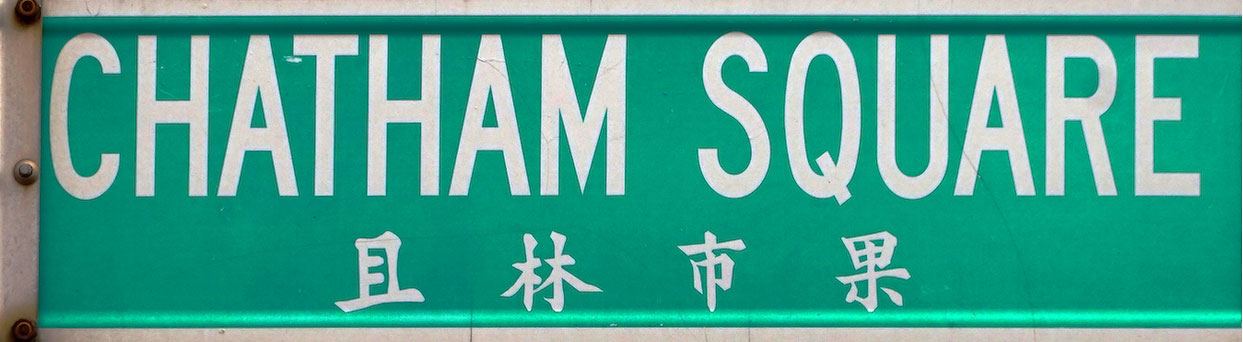

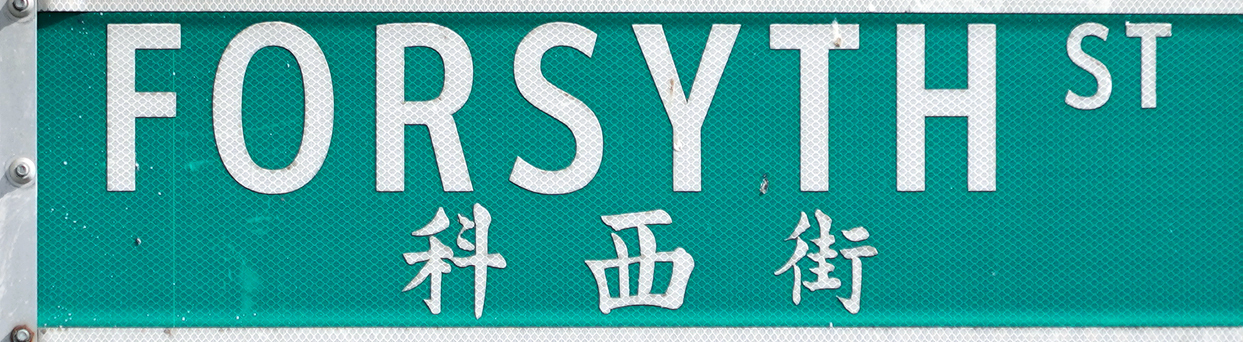

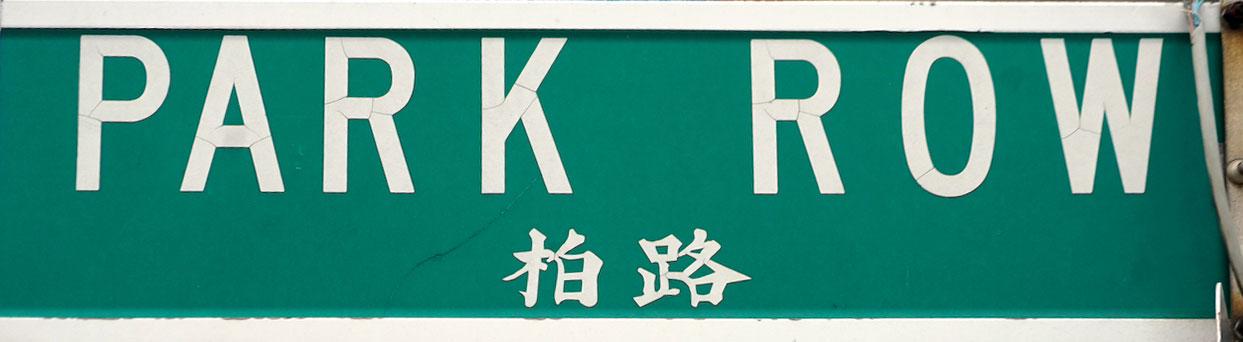

在十字路口,中英雙語標誌越來越少。

在紐約華埠年頭最久的熱鬧街道上,雙語路標已經存在50多年。它們是上世紀60年代一個項目的產物,旨在讓那些可能不認識英文的紐約華人更容易在附近街區尋路。

這些路標代表著對一個多世紀以來在這座城市被邊緣化的群體日益增長的影響力的正式認可。但在21世紀,隨著曼哈頓華埠作為紐約唯一中國文化中心的影響力逐漸減弱,這些獨特的基礎設施也開始慢慢消失。

自上世紀80年代以來,已有至少七個雙語路標被移除。

在1985年下令製作的至少155個雙語路標中,今天在華埠的20多條街道上還留有約100個。儘管關於被移除的路標沒有官方記錄,但《紐約時報》的一項分析發現了至少七個路標的影像證據,它們自1985年以來已被移除或替換為純英文路標。

現存雙語路標的位置

標籤處顯示了目前有雙語路標的街道

現存雙語路標的位置

標籤處顯示了目前有雙語路標的街道

現存雙語路標的位置

標籤處顯示了目前有雙語路標的街道

現存雙語路標的位置

標籤處顯示了目前有雙語路標的街道

標籤處顯示了目前有雙語路標的街道

現存雙語路標的位置

標籤處顯示了目前有雙語路標的街道

現存雙語路標的位置

《紐約時報》對來自谷歌街景歷史圖像的分析;來自由下東區歷史保護計劃製作的《Chinatown: Lens on The Decrease East Aspect》;美國華人博物館;Iron Sights Studio製作的《Coronary heart of Chinatown: A Panoramic Tour》。

關於該項目的大部分記錄要麼在交通局的一處辦公設施被淹毀,要麼在隨後的搬遷中丟失,要麼(正如本文幾位受訪的困惑官員所暗示的那樣)從一開始就沒有被記錄下來。

我們就所剩的資料開展了調查,試圖拼湊出該項目的歷史脈絡。

在已經被移除的雙語路標中,至少四處是近年拆除的。

根據交通局的說法,近來在施工過程中受損或被移除的雙語路標往往會被替換為純英文路標。

Canal Avenue at Allen Avenue

Catherine Avenue at Chatham Sq.

Canal Avenue at Allen Avenue

Catherine Avenue at Chatham Sq.

Canal Avenue at Allen Avenue

Catherine Avenue at Chatham Sq.

Canal Avenue at Allen Avenue

Catherine Avenue at Chatham Sq.

Google Avenue View and James Estrin/The New York Occasions

在紐約,來自近200個國家的300多萬居民會說超過700種語言和方言,雙語服務已經融入這座城市的生活。

紐約為投票、地鐵尋路和法庭訴訟等城市功能提供語言服務,並在市內一些少數族裔社區安置了單獨的非英語路標,比如韓國城的西32街又名「한국 타운」(韓國道),以及被稱為「露易賽達」(下東區)的C大道的一部分,這是在向波多黎各群體致敬。

Forsyth Avenue subsequent to the Manhattan Bridge, the place road distributors maintain a day by day open-air market.An Rong Xu for The New York Occasions

但華埠的路標和這些都不一樣:它們代表了整個華人社區與市政府攜手展開的大規模翻譯工作,最終創造出一個徹底雙語化的街道網。

這些路標的歷史講述了曼哈頓最大的移民群體之一成長、衰落和演變的故事。

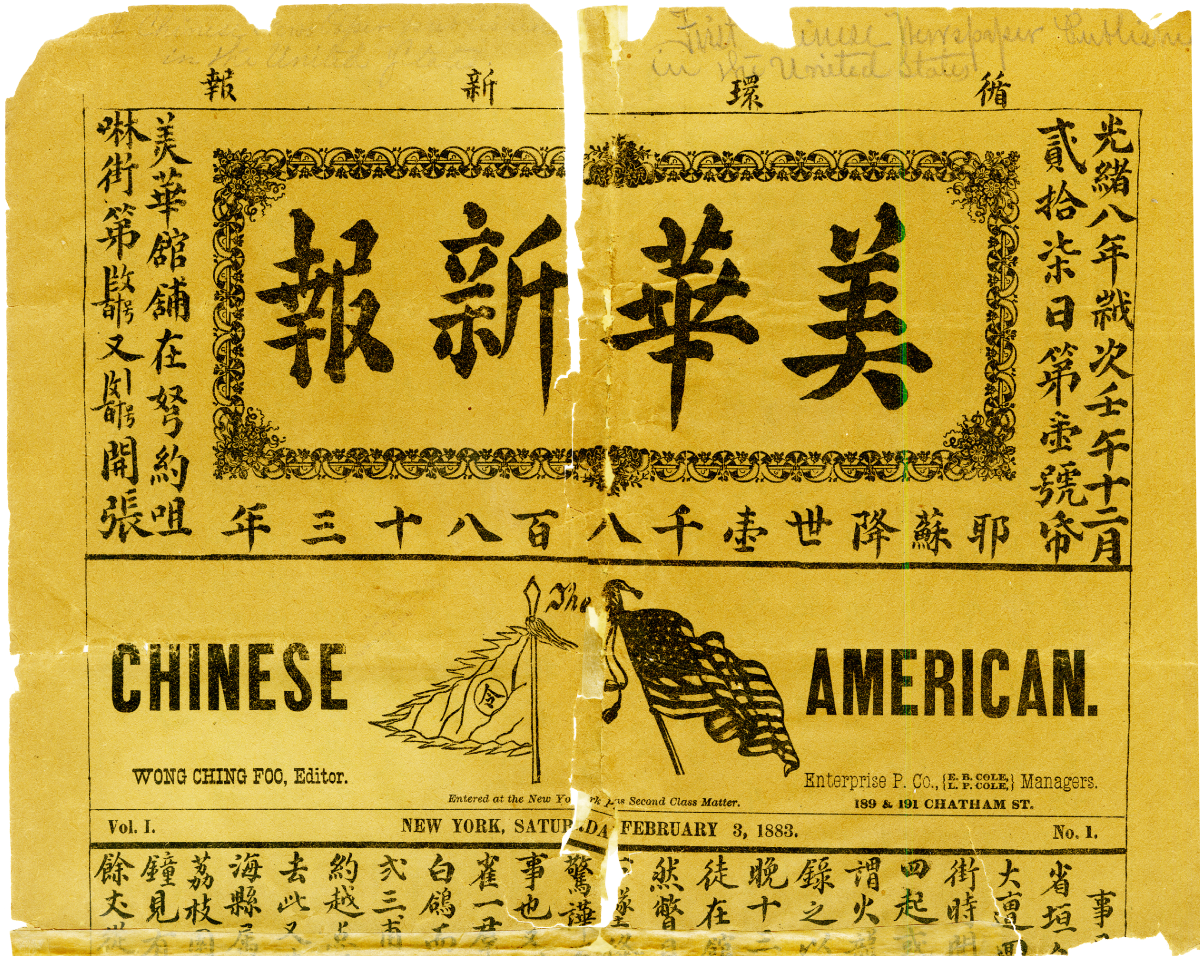

1883年,早年美國華人議題的作者和倡議人士王清福來到曼哈頓,創辦了紐約第一家中文報紙《美華新報》。他將報社總部選在了咀啉街(現在的柏路)的一個辦公地點,往北隔幾個街區就是後來紐約的第一處華埠所在地。

王清福寫道,他的目標就是「讓這份報紙滿足同胞們長期以來的需要,他們中能讀懂英文的人還不到千分之一」。

那之前的幾十年,大約是王清福來美讀大學的時候,紐約最早的一批華人就開始在勿街和披露街附近定居。在王清福接受美國教育的同時,隨著成千上萬的中國人被招募到橫貫大陸鐵路的建設中,來美的中國移民也不斷增加。他們往往面臨極其糟糕的待遇、法律歧視以及不公平的勞動法規,為此,王清福不斷撰文披露,並在全美各地發表演說。

曼哈頓的中文街名和華埠本身一樣古老。

王清福《美華新報》創刊號上的發行欄中,用中英雙語寫著該報的地址,中文名是音譯「咀啉街」。

Museum of Chinese language in America

1869年,在第一條橫貫大陸鐵路竣工之後,華人勞工突然找不到穩定工作了,並在西部各州面臨著不斷上升的種族敵意和暴力事件。越來越多的華人開始移居東部城市。到1883年王清福來到紐約時,曼哈頓華埠已經是中國移民的聚居地。

1900年前後的披露街,當時距離《排華法案》頒佈不到十年,該法案迫使美國華人進入了一個充滿暴力和恐嚇的殘酷新時代。隨著1885年懷俄明州石泉城大屠殺和1887年奧勒岡州地獄峽谷大屠殺等西部反華暴力事件的增加,曼哈頓華埠也成為了越來越有吸引力的去處。by way of Library of Congress

也正是在這個時候,華埠的商店櫥窗上和私人信件裡都開始出現非正式的中文街名。

1966年6月11日,約瑟夫·拉維利亞和克里斯·可倫坡這兩名穿著格子衫、剃著平頭的警察出現在且林士果廣場。市政府派他們到華埠的警用電話亭(在沒有手機的時代,這是撥通當地警局電話的快捷方式)安裝新標識。這些標識解釋了電話亭的用途及使用辦法——只不過是中文版。

「這個電話亭只有標識是雙語的,」時報在1966年的報導中寫道。「在標有中文的電話的另一頭,接聽者既不會講也壓根不懂中文。回應基本就是,『有什麼事——你不能說英語嗎?』」New York Occasions article printed on June 12, 1966.

1965年的《移民法案》通過後,來自中國各地的移民和海外華人僑民大量湧入美國,徹底改變了中國移民在美的處境。為了服務越來越多英語不流利的人,新的中文標識在紐約應運而生。

1969年1月15日,美國華商會的余炳輝和黃浩然與時任紐約交通督導員西奧多·卡拉格佐夫在該市首個雙語路標前合影。Carl T. Gossett/The New York Occasions

大約在同一時間,另一項幫助新移民熟悉社區道路的努力正在醞釀:作為聯絡華埠與紐約市政機構為數不多的地方組織之一,美國華商會向紐約市公共運輸局提出請求,為華埠製作、放置雙語路標,「讓成千上萬華人新移民生活更輕鬆,」時報在1969年報導稱,「這些人在抵美之初對英語或拉丁字母知之甚少。」

華埠影響力不斷提升,引發了與鄰近社區的衝突。

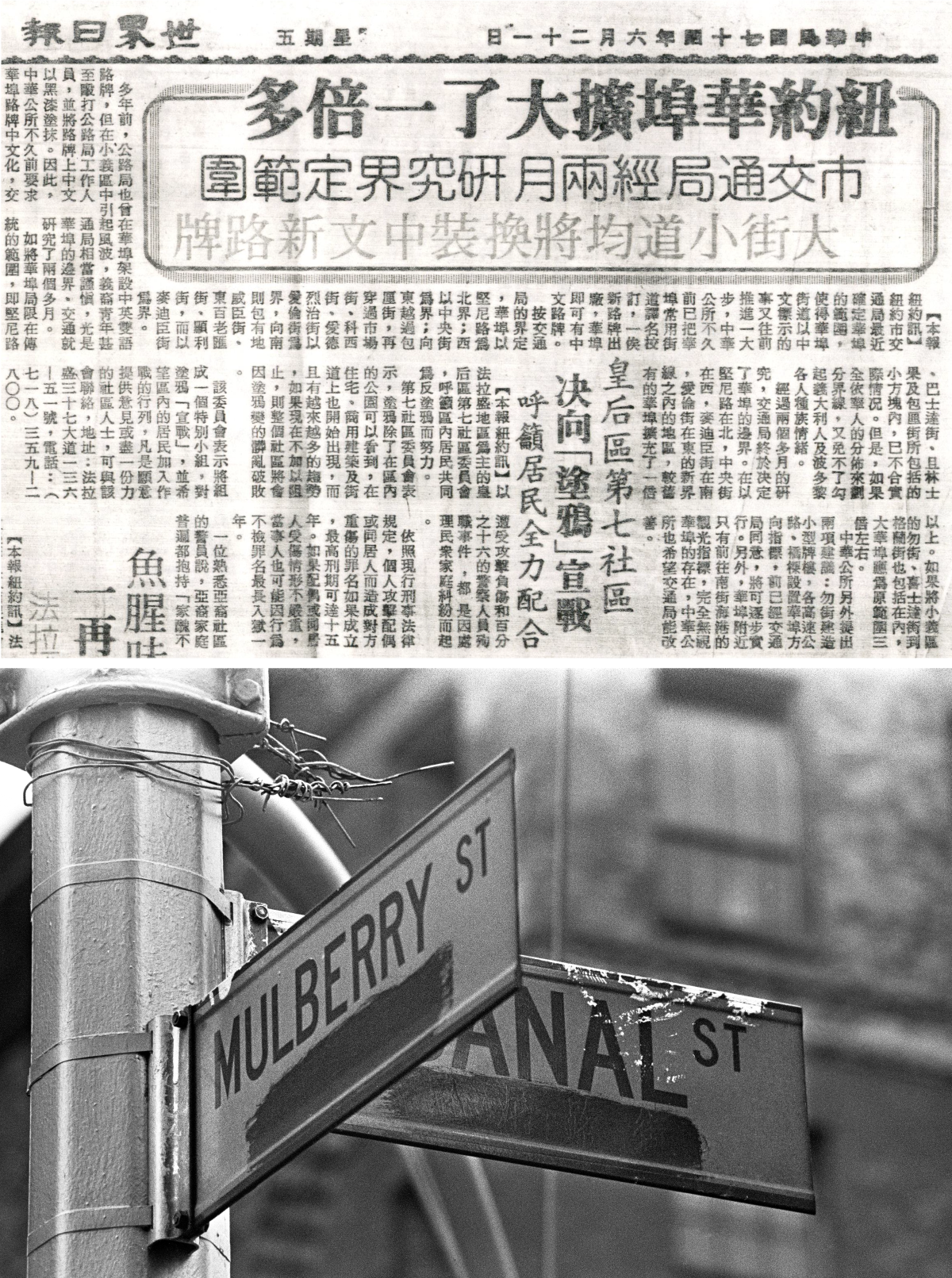

1985年,中文報紙《世界日報》報導稱, 雙語路標曾在多年前引來帶有種族主義動機的蓄意破壞和暴力事件,「義(大利)裔青年甚至毆打公路局工作人員」,並「將路牌上中文以黑漆塗抹」。

Jerry S.Y. Cheng and William E. Sauro/The New York Occasions

然而,使用「官方」中文街名的想法又引來了一個新問題:該起怎樣的中文名呢?雖然中文方言與書面語言(無論簡繁)相同,但每個漢字的發音在不同方言中可能會有天壤之別。

上世紀60年代末,華埠的大多數移民都來自中國南部的台山和廣州地區。雖然據報導稱,最終的中文街名是基於社區提交的意見書,選擇了便於持不同方言的移民理解的發音,但定下的街名仍然最清楚地反映了台山話和廣東話。

有兩種主要譯法。

直譯法:按詞義直接翻譯成中文,發音與英文原詞並無相似。

音譯法:用中文音譯,模仿英文原詞的發聲,但中文可能沒有意義。

多年來,根據譯者的不同理解,同一條街道曾被翻譯成不同的名字。以下是對東百老匯大街翻譯變化的示例。

1958年地圖中使用的街名

伊士

「East」的音譯法

布律威

「Broadway」的音譯法

東

「East」的直譯法

百老滙

「Broadway」的音譯法

一個中文街名可能有多種讀法。

英語中有幾個音在中文方言中不存在,這使得有時用漢字重現英文單詞會非常困難。此外,一個在粵語中可能聽起來與英文街名幾乎完全相同的名稱,在另一種方言中或許完全不同——與英語街名毫無相似之處。

英語粵語普通話台山話閩方言

且林市果

且林市果

英語粵語普通話台山話閩方言

科西街

科西街

英語粵語普通話台山話閩方言

柏路

柏路

英語粵語普通話台山話閩方言

勿街

勿街

Museum of Chinese language in America and Chang W. Lee/The New York Occasions

上世紀60年代末和70年代初,華埠變得更加多元。來自其他地區的移民越來越多,普通話、閩方言等也在這裡迅速蔓延開來。

1968年的勿街。與全美一樣,上世紀60年代末的華埠,年輕一代充滿政治活力,他們創辦了幾個活動人士和社區服務機構,這些組織在接下來的半個世紀裡塑造了華埠的公民社會。Don Hogan Charles/The New York Occasions

雖然這些路標未能呈現出中文方言的多樣性,但它們的出現代表了曼哈頓華埠一個突出的新時代,因為這片街區已經發展成為紐約華人繁榮的家園和商業中心。

在王清福將報社總部設在咀啉街的一百年後,一位名叫鄭向元的年輕城市規劃師沿著這條街走下去,想弄清楚且林士果廣場周圍混亂的交通狀況到底是怎麼回事。

從王清福抵達華埠到1965年《移民法案》通過,華埠人口已穩步增長至1.5萬人。鄭向元1969年從台灣移民至此,這裡的人口已經開始膨脹,到1985年居民人數達到了7萬人。以制衣業和餐飲業為動力,這裡的經濟迎來了蓬勃發展。生意更好了,商鋪更多了,人流量更大,交通也更壅堵了。

1977年的宰也街。Paul Hosefros/The New York Occasions

|60| 結果,鄭向元發現很多人來找他。「他們會帶著問題來找我,因為我是華人,」鄭向遠說。「我認識那些領袖,我能翻譯——我就像一座橋樑一樣。」

正是在這樣的背景下,鄭向元結識了中華公所主席李立波。中華公所是約60個團體組成的一個社群組織,長期以來一直是華埠的非官方(儘管經常存在爭議)治理機構。

路標上的手寫字體。

路標上的漢字由當地著名書法家譚炳忠親筆書寫。據當時的中文媒體報導,「他的筆法遒勁有力,為實用性的路標註入了藝術氣息。」雖然時任紐約市長郭德華(Edward I. Koch)沒有出席1985年官方路標的揭幕儀式,但他給譚炳忠寫了一封私人的感謝信。

New York Metropolis Division of Transportation and Chang W. Lee/The New York Occasions

細節差異使每個漢字都獨一無二。

因為每一個中文街名都是譚炳忠寫下的,細節處處有巧思。每個路標上幾乎都有「街」一字,但每個「街」字都有一些細微不同。

Chang W. Lee/The New York Occasions

1984年,李立波致電鄭向元討論路標一事。據一些估計,當時華埠的地理範圍已經增加了一倍,開始包括以往被認為是小義大利、包厘街和下東區的地方。當尼克森總統在1972年訪華和美中關係破冰之後,每年來到這裡的說普通話和福建話的移民越來越多。

在鄭向元的幫助下,中華公所向交通局提交了意見書,要求拓展雙語街名項目,以適應該地區的發展。

「交通局並沒有太多的反對,」時任副局長的戴維·古林說。「社區要求設立這些路標,這也算是與人方便。」

唯一的爭議是,這些中文路標的使用範圍,也就是華埠的邊界到底應該在哪裡。交通局似乎對華埠範圍進行過為期兩個月的研究,但研究結果大概率已經遺失。

該項目的記錄已丟失、毀壞或殘缺。

這張地圖(無符號表、圖例或腳註)和其他零散的記錄似乎表明,向北至布魯姆街、向西至拉法葉街之間的街道都曾考慮設置雙語路標。但參與該項目的在世者都無法給出確切答案。

圖中標出的就是交通局可能考慮過設置雙語路標的街道。

圈出區域中都設置了雙語路標。

圖中標出的就是交通局可能考慮過設置雙語路標的街道。

圈出區域中都設置了雙語路標。

New York Metropolis Division of Transportation

當我問鄭向元他是否還記得可能會有什麼記錄保存下來時,他大笑了起來。「不,不,我不認為會有,」他說。「我不認為還會有多少記錄留下來。基本所有參與過的人都過世了。」

我們知道,一旦設置雙語路標的街道確定下來,下一個障礙就又是該如何選擇中文名稱。這一次,做決定的人換成了中華公所一個由企業主、業主和長期居民構成的委員會,這些人主要講台山話和粵語。

曾做過城市規劃師的鄭向元。他的私人記錄和剪報收集幫助我們拼湊出這一獨特城市項目的歷史脈絡。An Rong Xu for The New York Occasions

他們當時要為一個與過去完全不同的華埠取街名,但所選街名還是基於台山話和粵語,忽略了華埠的大批新移民。

他們也沒有採納在華埠某些地方的常用通俗街名。比起英文街名,不同時代的中國移民所起的街名更能體現街道特徵。比如對於華埠的許多人來說,茂比利街就是屍體街,因為路旁都是殯儀館、花店和雕像店。許多這樣的街名至今仍被華埠居民使用。

現已停刊的華文報紙《北美日報》的一段剪報展示了1985年中華公所總部舉行的慶祝雙語路標拓展項目完成的儀式。李立波與戴維·古林(前中)合影,旁邊是交通局官員彼得·彭尼卡和伊麗莎白·西奧凡。在後排,鄭向元位於最右邊,左起第二人是譚炳忠。Jerry S.Y. Cheng

對華裔和華裔美國人來說,華埠仍是充滿活力的文化中心,也是華人新移民的落腳點,但這個社區的規模正在縮小。根據2020年人口普查,亞裔是紐約市增長最快的社群。然而,即便定居在布魯克林和皇后區的人越來越多,華埠還是經歷了紐約所有社區中最嚴重的亞裔居民外流。

這些變遷至少可以追溯到2001年9·11事件的累積效應;襲擊的後果對華埠經濟造成了巨大打擊,特別是餐飲和製衣業。另外,炒房和外商投資推高了租金,再加上最近的新冠疫情導致種族主義言論和暴力事件增多,也令附近商鋪生意蕭條。

東百老匯大街的一家商鋪,這是歷史悠久東百老匯購物中心僅剩的少數租鋪之一。這座產權屬於市政的商場被當地福建人稱為怡東樓,是一處重要商業空間,曾容納大約80家小企業。新冠疫情已導致這裡超過四分之三的租鋪停業,未來吉凶難卜。An Rong Xu for The New York Occasions

近年來,華埠的努力被引向社區組織和示威活動,例如反對金豐大酒樓(一家歷史悠久的早茶餐廳,也是華埠最後一家有工會的餐廳)關張,反對在社區中心地段建造新監獄,反對最近的城市重新區劃、社區士紳化以及遷移問題。公園和廣場處處都能見到反亞裔暴力的抗議活動。在這些人們更為關心的鬥爭面前,雙語路標這樣的議題似乎很難再受到關注。

或許這就是很多人還沒意識到雙語路標也在消失的原因。

華埠現僅存101個雙語路標。在該項目的高峰期,至少有155個雙語路標被下令印製。在譚炳忠受邀寫下的40個街名中,近一半的街道已不再保留任何雙語路標。根據交通局副新聞秘書阿拉娜·莫拉萊斯的說法,「中英雙語路標不在美國交通運輸部《道路交通管理標誌統一守則》的要求之中。」這意味著如果雙語路標被撞倒或損壞,她表示,「它們將被英文路標替換。」

加薩林街上損壞的雙語路標,可能會被替換為純英文路標。Chang W. Lee/The New York Occasions

上世紀80年代參與過雙語路標推廣的許多人都已去世,維繫該項目的壓力已經很小。在這座城市看來,這些路標屬於一個將會慢慢消失的一次性項目,而不是城市基礎設施的永久組成部分。

在如今的華埠,中華商會和中華公所這樣的組織仍有其影響力——例如,當地政客若是尋求華埠支持,它們依然是常規的拜訪處。但隨著社區多樣化,這些組織作為城市與社區之間主要紐帶的時代已經過去。

與此同時,許多新的倡導組織已經興起,提出了新的優先事項,服務華埠的不同群體,重點關注保障性住房、遷移、社區服務和新冠疫情補助等問題。

在接受本文採訪之前,當地居民、社區組織者、企業主或學者中沒有任何人意識到,這些路標正在消失。

New York

Video: One Housing Project Got Built. Another Didn’t. Why?

There’s a solution to New York City’s housing shortage: Build more homes. But that can get complicated. Mihir Zaveri, a New York Times reporter covering housing in the New York City region, explains why one project got built and another did not.

New York

Dining Sheds Changed the N.Y.C. Food Scene. Now Watch Them Disappear.

On Halloween, Piccola Cucina Osteria Siciliana in SoHo served one last dinner in the little house that it built on Spring Street during the first year of the coronavirus pandemic.

Lila Barth for The New York Times

The next morning, the owner, Philip Guardione, took everything he could save from the structure: 11 tables, chairs, live palms and ZZ plants, basket-shaped rattan chandeliers, space heaters. The rest — including white window shutters with adjustable louvers meant to give diners the feeling that they had arrived home at the end of the day — was hauled off by a trash-removal company.

Lila Barth for The New York Times

Once the scrap wood was gone, the site where Piccola Cucina had served wine from Mount Etna and Sicilian classics like bucatini with sardines and fennel reverted to what it had been before the pandemic: a street-parking space, one of almost three million in New York City.

Lila Barth for The New York Times

Four years after in-street dining gave desperate restaurants a way to hang on and New Yorkers a way to hang out, the very last of the Covid-era dining sheds are truly, finally, really disappearing.

The structures varied from simple lean-tos banged together out of a few hundred dollars’ worth of lumber to small, lovingly detailed odes to verdigris Beaux-Arts winter gardens, sleek Streamline Moderne luncheonettes and sunset-pink Old Havana arcades.

They came to have almost as many meanings as architectural styles. To some urbanists, they were a bold experiment in rethinking public space. To others, they were an eyesore. Restaurateurs saw them as an economic lifeline. Opponents saw a land grab.

Dining inside a popular spot, you could believe New York had embraced al fresco culture like Rome and Buenos Aires. Walking past an empty one at night, you might conclude that the city was throwing a permanent picnic for the rats.

It was never meant to last, at least not in the form it took during the depths of the pandemic. The city’s street-and-sidewalk dining program, called Open Restaurants, used an emergency executive order to allow restaurants to sidestep many existing laws and regulations about safety, parking, accessibility and fees.

Once the emergency ended, permanent rules were written after much wrangling between Mayor Eric Adams, the City Council, a herd of bureaucracies and the restaurant business. The guidelines are now far more stringent: Fully enclosed structures aren’t allowed, for instance, and many setups will have to be scaled back to a smaller footprint.

A dining shed that complies with the new rules in use at Dawa’s in Woodside, Queens.

Karsten Moran for The New York Times

There were so many noncompliant shacks still standing that hauling companies and contractors have had a backlog of several weeks. All street sheds, even the ones that meet the new requirements, are supposed to be removed by the end of the day on Nov. 29. According to the Department of Transportation, any structures still standing the next day will be subject to fines of up to $1,000.

The season reopens April 1, creating a storage challenge for restaurants, which are not known for having lots of extra space.

As of Thursday, the Department of Transportation, which oversees the new program, had received 1,412 applications for roadway dining permits next year — a dramatic drop from the 12,000 businesses that applied under Open Restaurants.

Some owners are bitter about giving up roadway seating for the winter, particularly in December, the busiest month. (There are new rules for sidewalk cafes, too, which are allowed year-round.)

Restaurants excel at conjuring whole moods out of next to nothing. The New York Times took a closer look at several restaurants that have already taken down their creative street setups, and a few that have been holding out.

Building for the Long Haul

Balthazar, SoHo, Manhattan

Jonah Rosenberg for The New York Times

Jonah Rosenberg for The New York Times

Jonah Rosenberg for The New York Times

Jonah Rosenberg for The New York Times

The Open Restaurants program was originally scheduled to end after Labor Day in 2020. Few owners wanted to invest in such a short-term proposition, and many of the flimsier structures that were knocked together that summer were abandoned or falling down by the time winter came.

Balthazar took a longer view.

It waited a full year before coming back in March 2021, with three tented cabanas on Spring Street that were built to last. A peaked roof of red fabric matching the restaurant’s awnings was stretched over a sturdy metal frame. A wainscoted ledge next to the tables disguised heavy barriers that have withstood several run-ins with passing trucks. The floors were a water-resistant plywood that was dyed, not painted, so its deep blue wouldn’t be scuffed away.

The goal was not to make it look new. Ian McPheely of the firm Paisley Design worked to give the cabanas the soft, timeworn look that he helped bring to the restaurant’s interior when it was built in 1995. Keith McNally, the owner, obsessed over the lighting, finding antique table lamps and hanging globe lights that matched the ones inside.

“When you step into Balthazar, you feel like you’ve taken a train to Paris, and you needed to have that same sense outside,” said Erin Wendt, the director of operations for the Balthazar Restaurant Group.

When the cabanas were built, indoor dining was limited to 25 percent of capacity. The cabanas had space for about 40 seats and operated seven days a week, morning to night. The added revenue quickly covered their cost, which the chief executive of Balthazar’s restaurant group, Roberta Delice, placed at about $160,000. American Express and Resy picked up around $40,000 of the cost through a pandemic promotion.

Ms. Wendt said that after the structures were hauled off on Nov. 1, the restaurant had 72 fewer weekly shifts to offer its employees.

“We’re going to do everything we can not to lay people off, but everybody is going to take a hit,” Ms. Wendt said.

From Eyesores to Gardens

Cebu, Bay Ridge, Brooklyn

Marissa Alper for The New York Times

Marissa Alper for The New York Times

Marissa Alper for The New York Times

Marissa Alper for The New York Times

Michael Esposito estimates that he poured between $75,000 and $100,000 into the two decks he built in front of Cebu Bar & Bistro. Street dining at Cebu began in late 2020 with movable barricades separating diners from the traffic.

Eventually, with his partner and his contractor, he designed one structure that stretched for 65 feet along Third Avenue and a second one, about half as long, on 88th Street. The sheds were wired for lights, space heaters and speakers.

A floral-design company was hired to turn these big black boxes into urban arbors. Cascades of artificial wisteria swayed below the ceiling, supplemented by live palms and ferns.

“We definitely wanted to look our best for everybody,” said Mr. Esposito, the owner. “If you go by one of the sheds that’s falling apart and filthy, it’s not a good representation of what’s going on indoors.”

He said he suspects his efforts to dress up the avenue may have smoothed the way with the local community board, which recently approved Cebu’s plan to come back in April with a street-dining area that meets the city’s new rules.

Mr. Esposito’s proposal has room for 75 seats, about three-quarters of what he used to have. When the old structures were taken down on Nov. 8, much of it went into storage in the hopes that it can be repurposed next year. The roofs had to go, though, and he will not have as many hours to offer his employees, especially over the winter.

“We’re still fortunate to be given the opportunity so I’m not going to complain at all,” he said.

Privacy on a Busy Street

Don Angie, West Village, Manhattan

Jonah Rosenberg for The New York Times

Jonah Rosenberg for The New York Times

Jonah Rosenberg for The New York Times

Jonah Rosenberg for The New York Times

The public-health rationale for outdoor dining was that fresh summer breezes could help slow the spread of the coronavirus. But as the weather turned cold, restaurants faced a new challenge: keeping their customers safe and warm.

Don Angie came up with an innovative solution: two “cabins” with a total of nine private compartments. Designed by GRT Architects, each room had baseboard heating, insulated walls, velvet curtains at the entrance and space for up to six people. Clear plexiglass dividers let customers see other diners without having to share their air.

Scott Tacinelli and Angie Rito, the chefs, taped parallel rows of auto-detailing decals over the partitions to give them vertical pinstripes.

“It took a really long time to get them straight,” Ms. Rito said. “Scott and I took a whole day to put up those lines.”

“It was more than a day,” Mr. Tacinelli said. (The two are married.)

Diners, and celebrities in particular, appreciated the privacy they could get by drawing the curtains. Some cabin regulars have yet to set foot inside the restaurant, the chefs said.

The two cabins cost about $75,000. The larger one was demolished last year, and the remaining one was hauled away on Nov. 12. To make up for some of the business they will lose over the winter, the chefs are thinking of serving lunch on Fridays and staying open an extra half-hour each night, although people aren’t as willing to eat late as they were before the pandemic.

Although they have applied for permits for the new program, they said they aren’t sure yet what their new structures will look like.

Still Standing, For Now

Empire Diner, Chelsea, Manhattan

Lila Barth for The New York Times

As the Nov. 29 deadline approaches, many street structures are still in place around the city.

Empire Diner, the 1946 stainless steel dining car on 10th Avenue, is hoping to keep the slim, monochromatic building it calls the Pavilion right up to the last minute, said Stacy Pisone, one of the owners.

Designed by Caroline Brennan of the firm Silent Volume in 2021, and built at a cost of $150,000, the structure echoes the diner’s streamlined Art Deco contours. Portholes cut into white panels alternate with the vertical plexiglass windows that wrap around three sides of the structure. When a coalition of urban-planning groups that supported street dining gave awards to seven outstanding structures in 2021, the Pavilion was one of the honorees.

Ms. Brennan wanted to give people eating in the Pavilion’s 40 or so seats something to look at, and the Brazilian street artist Eduardo Kobra was commissioned to paint a wall above the diner. In a nod to West Chelsea’s galleries, the mural features portraits of Andy Warhol, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Keith Haring and Frida Kahlo.

“We call it Art Rushmore,” Ms. Pisone said.

Neighbors, including some of the local gallerists who often rented out the space for dinners, have suggested a big, celebratory send-off inside the Pavilion before it is torn down. Ms. Pisone, who hasn’t scheduled the demolition yet, doesn’t have the heart for it.

“I can’t even think about doing a party,” she said. “It’s just so sad.”

Ayza, NoMad, Manhattan

Lila Barth for The New York Times

East of Herald Square, Ayza Wine Bar is trying to hang on to its outdoor dining area through the end of the year. Partly, the owners hope to take advantage of the busy holiday season. Mostly, though, they are confused about how the new rules affect them, because the regulations were written for structures, and what Ayza has on East 31st Street isn’t a structure, exactly.

It’s a trolley car.

This struck Ayza’s owners as an ingenious solution during the pandemic. Purchased from a sightseeing-tour company in Boston and refurbished with 20 seats at a total cost of about $25,000, the trolley had large, unobstructed openings that allowed air circulation. Its dimensions were almost exactly what the city allowed. Because it was up on wheels, rain water ran right under it. And because it was more solidly built than the typical wooden shed, it was safer from minor collisions.

“I would feel bad for the person who hits the trolley,” said Zafer Sevimcok, one of the owners.

Mr. Sevimcok said he has applied for permission to operate in the street next year. He isn’t sure whether his application will be approved, though, because the new regulations do not have a trolley option.

In case the city cracks down, he has a backup plan: He will call a mechanic to charge the battery and then drive the trolley away

Restaurant Photography: Lila Barth for The New York Times (Piccola Cucina, Empire Diner and Ayza). Jonah Rosenberg for The New York Times (Balthazar, Don Angie, Oscar Wilde). Marissa Alper for The New York Times (Cebu). Karsten Moran for The New York Times (Dawa’s).

Produced by Eden Weingart and Andrew Hinderaker

New York

Map: 2.3-Magnitude Earthquake Strikes Connecticut

Note: Map shows the area with a shake intensity of 3 or greater, which U.S.G.S. defines as “weak,” though the earthquake may be felt outside the areas shown. The New York Times

A minor, 2.3-magnitude earthquake struck in Connecticut on Wednesday, according to the United States Geological Survey.

The temblor happened at 7:33 p.m. Eastern about 1 mile northwest of Moodus, Conn., data from the agency shows.

As seismologists review available data, they may revise the earthquake’s reported magnitude. Additional information collected about the earthquake may also prompt U.S.G.S. scientists to update the shake-severity map.

Aftershocks in the region

An aftershock is usually a smaller earthquake that follows a larger one in the same general area. Aftershocks are typically minor adjustments along the portion of a fault that slipped at the time of the initial earthquake.

Quakes and aftershocks within 100 miles

Aftershocks can occur days, weeks or even years after the first earthquake. These events can be of equal or larger magnitude to the initial earthquake, and they can continue to affect already damaged locations.

Source: United States Geological Survey | Notes: Shaking categories are based on the Modified Mercalli Intensity scale. When aftershock data is available, the corresponding maps and charts include earthquakes within 100 miles and seven days of the initial quake. All times above are Eastern. Shake data is as of Wednesday, Nov. 20 at 7:41 p.m. Eastern. Aftershocks data is as of Wednesday, Nov. 20 at 11:34 p.m. Eastern.

-

Science1 week ago

Science1 week agoDespite warnings from bird flu experts, it's business as usual in California dairy country

-

Health1 week ago

Health1 week agoCheekyMD Offers Needle-Free GLP-1s | Woman's World

-

Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoLost access? Here’s how to reclaim your Facebook account

-

Entertainment6 days ago

Entertainment6 days agoReview: A tense household becomes a metaphor for Iran's divisions in 'The Seed of the Sacred Fig'

-

Technology5 days ago

Technology5 days agoUS agriculture industry tests artificial intelligence: 'A lot of potential'

-

Sports4 days ago

Sports4 days agoOne Black Friday 2024 free-agent deal for every MLB team

-

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23906797/VRG_Illo_STK022_K_Radtke_Musk_Scales.jpg)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23906797/VRG_Illo_STK022_K_Radtke_Musk_Scales.jpg) Technology3 days ago

Technology3 days agoElon Musk targets OpenAI’s for-profit transition in a new filing

-

News2 days ago

News2 days agoRassemblement National’s Jordan Bardella threatens to bring down French government