Boston, MA

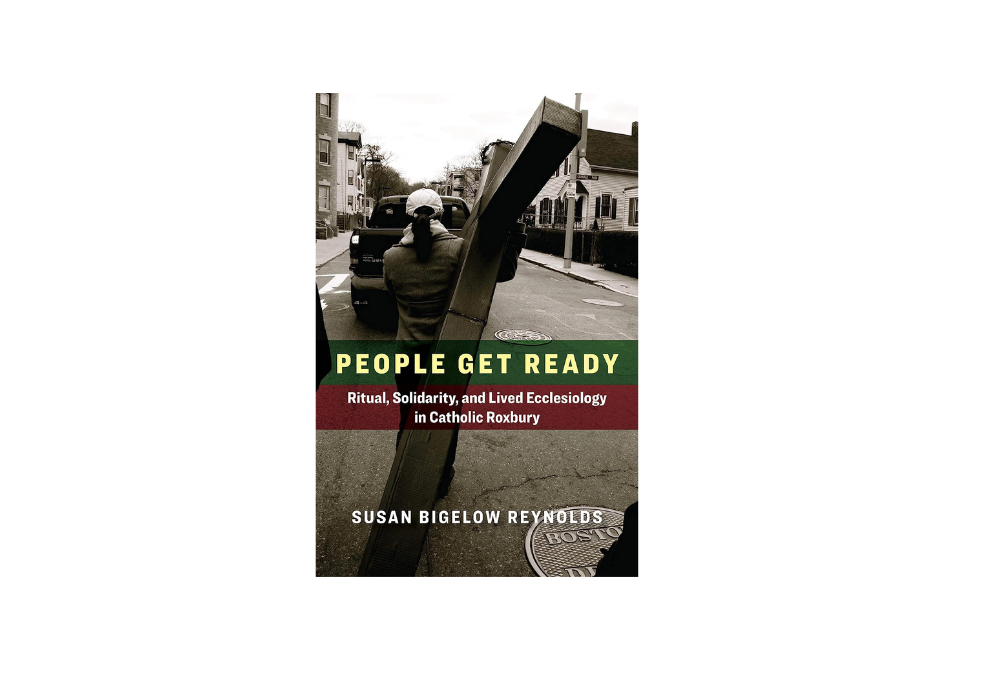

‘People Get Ready’: Boston-area parish offers lessons for wider church

What a blessing it would be if every parish had a sympathetic and penetrating chronicler like Susan Bigelow Reynolds, whose book People Get Ready: Ritual, Solidarity, and Lived Ecclesiology in Catholic Roxbury examines St. Mary of the Angels Parish in that Boston neighborhood.

Reynolds, who teaches theology at Emory University in Atlanta, would probably counter that observation with a different one: What a blessing it would be if every parish had the sense of shared community and commitment, of solidarity, as the people who belong to this small church in Roxbury’s Egleston Square. Perhaps, better to say, that the church belongs to them rather than that they belong to it.

Like many Boston churches, St. Mary’s was built, actually half-built, along the transit lines connecting Roxbury with downtown, but it was a small, territorial parish, with two ethnic parishes, one German and one Polish, nearby. Soon, Jewish immigrants came to the neighborhood. St. Mary’s parishioners worshiped first in the railway car barn, and in 1908 moved to the basement of the church. The funds and the families to build the church above never materialized, and when Reynolds arrived in 2011, while studying at Boston College, the congregation still worshiped in the basement church.

The lens Reynolds applies is ethnographic and, as she explains the history of the church, the choice of lens seems obvious. “St. Mary of the Angels is a parish on and of the margins,” Reynolds writes. “For more than a century, its small boundaries have encompassed some of Boston’s most consequential religious and racial borderlines.”

She goes on to note that, “In an otherwise highly segregated city and church, St. Mary’s had become a hybrid parish formed over time by successive migrations.” Some migrated from other countries, others migrated from parishes across town that had become unwelcoming. A few migrated from other denominations: Before World War II, many Black people settled in Roxbury as two Black Protestant churches opened in 1926 and 1939. The 1960s saw an influx of migrants from the Caribbean. By 1986, the pastor reported to the archdiocese that the parish served “five hundred to six hundred people representing forty-three different countries of origin.”

The fact that migration played a part in bringing so many parishioners to the basement church made it an ideal candidate to embrace and live out the image of the church as the pilgrim people of God, articulated at Vatican II. Reynolds further argues that “recovering the ecclesiological significance of difference requires centering reflection precisely at the site of difference — both the sources of rupture and the moments of embrace.”

Reynolds chronicles the unsuccessful effort to revitalize “inner-city” ministry and evangelization launched by Boston’s legendary Cardinal Richard Cushing, a great champion of the Civil Rights Movement, in the 1960s. The top-down effort came to naught, and Reynolds contrasts that want of success with the seemingly less ambitious, but ultimately more fruitful, establishment of a parish council in 1969. “Seizing the postconciliar ethos of openness and collaboration, laity leaned hard into their newfound power in order to place their struggling parish into a relationship of costly solidarity with the increasingly marginalized community it served,” Reynolds observes.

Two early parish council initiatives caused worry within the archdiocesan chancery but ultimately received Cushing’s approbation: the transfer of parish funds to a local, community bank, and gaining a dispensation to hold vigil Masses on Saturday so that the working people in the parish could enjoy their one day of rest with their families. These early exercises in lay leadership would continue and blossom, culminating in the successful effort to resist closing the parish in 2004.

‘The dynamics that have shaped St. Mary’s for a century are today transforming the entire landscape of U.S. Catholicism.’

—Susan Bigelow Reynolds

Reynolds’ chapter on the neighborhood Way of the Cross displays her passion for the particularities of the story she is telling, as well as her capacity for analysis and fine prose. “Taking a different route every year, the procession invariably crosses neighborhood boundaries, gang territories, and parish lines as it weaves together the stations into a single path, as though embroidering a new map on top of an existing one,” she writes.

The ritual, which stops at the sites of recent tragedies in the community, also does more than fashion a new divinely touched map over Roxbury’s sufferings. “Resisting interpretations of ritual as a form of narrow meaning-making or as the bearer of a singular, all-encompassing ecclesial culture, I contend instead that the Roxbury Way of the Cross can be understood as a form of practical action that affirms solidarity in difference.” Anecdotes demonstrate how the various individuals within the parish negotiate their differences while respecting them.

Later chapters discuss other ways ritual “affirms solidarity in difference.” The parish council meetings are understood as rituals in themselves, starting with the reading of the parish mission statement in both English and Spanish. So, too, is the jumbled seating on Palm Sunday when no one ends up in their usual pew. The welcome extended during the parish announcements is another: “We want to begin by welcoming those who are here for the first time, or those who have been away for a while and returned,” which Reynolds notes is the first time she has heard a welcome extended to fallen away Catholics, despite all the fretting about their departure! The regular efforts to arrange transportation for elderly parishioners, the potluck meals, the to-and-fro in the parish house, all attest to a vibrancy most parishes would envy.

It is impossible not to recognize how remarkable a parish St. Mary of the Angels is. It is also hard not to see how this parish, unlike most, successfully fought off the 2004 attempt to close it as part of the diocese-wide restructuring, arguing that the little church was an indispensable part of the neighborhood. If there is a better illustration of the changed self-understanding of the church implicit in Gaudium et spes, the Vatican II document on the church in the modern world, I do not know it.

Reynolds sees in St. Mary of the Angels not only an exceptional parish but a paradigmatic one.

“The dynamics that have shaped St. Mary’s for a century are today transforming the entire landscape of U.S. Catholicism,” she writes. “Among these are new and expanded contexts of migration, sweeping regional shifts in parish growth and decline, an ever-increasing need for lay leadership, limited resources, deep institutional mistrust and betrayal propelled by the clergy sex abuse crisis, and mounting calls for racial and economic justice.”

But there is one regard in which the Roxbury parish is exceptional that will limit the degree to which it can be paradigmatic. For a variety of reasons and in a variety of ways, St. Mary of the Angels is an intentional community. Yet, it is the genius of Catholicism to make a home for the B+ Catholics, and the C+ Catholics too, for the slackers, for those whose sense of community lies elsewhere but who still wish to find some communion with God and find it at Mass. A parish like St. Mary’s is likely too much for them. Every major city has a few parishes like St. Mary’s, refined in the fire of tribulations and overflowing with a life-giving spirit. They stand as a critique of the less-committed expressions of the faith. But they are exceptional.

In each chapter, interviews with parishioners bring the story alive and Reynolds weaves the whole into a narrative that is both readable and serviceable. After all, she is a theologian, not an historian, and this story has a purpose.

Solidarity is, for Reynolds, the great untapped ecclesiological principle of Vatican II. Yes, yes, solidarity has shaped our social ethics, and even our Christian anthropology. But, in her first chapter, she argues that the post-conciliar emphasis on communion ecclesiology undervalues the significance of difference.

“I argue that Vatican II laid the groundwork for an understanding of the parish as a school of solidarity,” Reynolds writes. “Yet as magisterial attention shifted to emphasize communion ecclesiology as the predominant interpretation of Vatican II’s ecclesiology, the ecclesiological implications of the council’s vision of solidarity have gone largely overlooked.”

She criticizes communion ecclesiology specifically for “ignoring the stark asymmetries of power that definitively shape the liturgical, sacramental and social life of a parish.” The “communion paradigm ultimately underwrites ecclesial colorblindness and renders unclear the mission of the local church with respect to racial justice.”

If so, and Reynolds makes a good case, this is a serious flaw in communion ecclesiology, and one it must address. I am not sure it is a fatal flaw, nor that the ethnographic perspective she employs does not also leave out integral aspects of a viable ecclesiology.

But here is the thing. This is a thoughtful, insightful book. It is not given to exaggeration, nor to a facile adoption of a “prophetic stance” that corresponds little with the stances taken by prophets in Scripture and more to the academic fads of the day. I could quibble with this observation or that, but none of the quibbles rise to an indictment.

I venture the hope that this book will also become seminal, that is, it will start a dialogue and debate between those theologians who, like Reynolds, employ ethnographic analysis and those theologians who cling to the communion ecclesiology that has so shaped the post-conciliar magisterium. Certainly, as Reynolds argues, the idea of an ecclesiology of solidarity could yield important correctives for a U.S. church that has difficulty resisting the cultural forces of the ambient culture, especially its comprehensive libertarianism from the boardroom to the bedroom.

American Catholic theology is in a state of crisis, and we need more theologians like Reynolds who engage the arguments of those with whom they disagree, do so respectfully, and put forward their own arguments with clarity and charity both. This is an excellent book and it should be read by a wide audience.

Boston, MA

Showcase gives ballplayers place to show their stuff

The dream of virtually any high school baseball player in Massachusetts is to get an opportunity to compete at the next level.

Dan Donato is hoping to make some of those dreams come true.

For the third straight year, Donato has spearheaded the New England Elite 100 Showcase, designed for high school baseball players looking to get noticed by college coaches at all levels. The two-day event will take place at Boston College on June 4-5.

“The numbers are coming in but we appear to be 15 ahead of last year’s pace,” said Donato, the head baseball coach at No. 1-ranked Dexter Southfield. “I think we’ve gotten to the point where this event is a must for any kids who want to play in college.”

A two-sport standout at Catholic Memorial, Donato went on to play hockey and baseball at Boston University. Following college, Donato had a minor league career in both the New York Yankees and Tampa Bay (Devil) Rays organizations, getting as high as Triple-A.

In his travels as a player and later as a coach, Donato noticed a growing number of baseball camps and clinics popping up in the south. He often wondered why a similar format couldn’t work in the north, leading to the creation of the New England Elite 100 Showcase.

“You would go to places like Georgia and see these great showcases,” Donato said. “The reality of the situation is that 90 percent of the kids who play high school baseball around here are likely going to play college baseball somewhere in New England.”

The early success of the camp has allowed Donato to bring in some of the top local high school coaches to help run things. Among those on the staff include Rick Forestiere, who climbed on board from Day 1; Jonathan Pollard (Austin Prep); David Cunningham (Belmont Hill); David Cataruzolo (Roxbury Latin); and former major leaguer Matt Duffy, a group which has more than 100 years of coaching under their collective belts.

The first day serves as a showcase for kids to display their talents in a variety of drills. The next day will consist of a series of games in which every kid is guaranteed a minimum of three at-bats a game and every pitcher would get an opportunity to throw 20-30 pitches. Donato thinks this is more than sufficient for a player to showcase his skills in front of a bevy of coaches from the likes of Harvard, Dartmouth, Boston College, Northeastern, Bryant, as well as Saint Anselm and the NESCAC.

“This is a great opportunity for kids who want to play college baseball to be able to have that chance to do it locally,” Donato said. “They’re going to get a chance to be seen by coaches from Division 1, 2 and 3. No matter what you are as an athlete, there is a home for anyone who wants to play college baseball.

“All I am trying to do here is help kids achieve their dreams of playing at the next level. It’s hard enough to play college baseball and it’s become even harder because of the transfer portals. I’ve coached for 25 years and I just want to do anything possible to help kids get to the next level whatever it happens to be for them.”

For further information, contact Tim Fledderjohn at fledd@premierfootballconsulting.com

Boston, MA

Thanks for the memories: All the top moments from Boston Calling 2025 – The Boston Globe

Boston Calling 2025 photos and highlights

Cowboy (and rain) boots were the attire du jour for Boston Calling on Friday, as the wettest day of the fest collided with its country-heavy billing.

The first night also brought faithful Fenway vibes as fans joined a “Sweet Caroline” singalong during a rain-soaked intermission while waiting for headliner Combs to perform. The short delay before his set proved to be worth the wait, as the country star charged up the Green Stage and “didn’t let up for an hour and a half,” according to Globe reviewer Marc Hirsh.

The “When It Rains It Pours” singer’s set featured a cameo by fellow country star Megan Moroney, who performed earlier in the night on the Green Stage. She rocked a personalized Red Sox jersey while joining Combs for a rendition of his song “Beer Never Broke My Heart.” Combs noted in an Instagram post that Moroney had been an extra in the song’s music video and asked her to jump in on Friday night when he saw they “were playing the same festival.”

Other highlights from the day included Sheryl Crow, rewarding fans who weathered the late-afternoon rain with crowd-pleasing hits like “Soak Up The Sun.” She offered a small bit of political commentary too, at one point shouting out, “I don’t know, Bruce Springsteen for president?” while wearing a T-shirt featuring the rocker.

Meanwhile, singer-songwriter Max McNown played up to the New England crowd by performing the Noah Kahan’s “Stick Season,” calling the Vermont crooner, “one of my greatest inspirations.” Over on the Blue Stage, rapper T-Pain showed off his dance moves and kept the party going with nostalgic bangers like “Buy You A Drank (Shawty Snappin’)” and “All I Do Is Win.”

Boston band Dalton & the Sheriffs served as a last-minute replacement for TLC. The R&B group dropped out “due to an unexpected medical circumstance,” the fest announced early Friday afternoon.

Read Globe correspondent Marc Hirsh’s day one review here and check out more photos from Friday below.

Saturday’s lineup was a trip down memory lane for millennial pop-punk fans, culminating with headliners Fall Out Boy. From hits like “Thnks fr th Mmrs” to newer tracks like “So Much (for) Stardust,” the band surveyed its lengthy discography, with plenty of pyrotechnics thrown into the mix.

Fans who caught Fall Out Boy’s set were treated to another “Sweet Caroline” moment, as singer Patrick Stump broke out the Neil Diamond tune during a brief piano interlude. The band also teased the opening to the Dropkick Murphy’s “I’m Shipping Up to Boston” before diving into “Bang The Doldrums.”

Avril Lavigne also brought the pyrotechnics and a heavy dose of pink pop punk aesthetics to the Green Stage with her early 2000s angsty teen anthems like “Sk8er Boi.” Lavigne later brought singer Alex Gaskarth from All Time Low out to perform their recent track “Fake As Hell.” (All Time Low performed earlier in the day on the Green Stage as well.)

The Maine, Black Crowes, Cage the Elephant, and James Bay were also among Saturday’s lineup of performers.

Read Globe correspondent Victoria Wasylak’s day two review here and check out more photos from Saturday below.

The final day of the fest brought the best weather, along with a mix of poignant tributes and political moments on stage.

Headliner Dave Matthews Band wound back the clock to the ’90s as the group played hits like “Tripping Billies.” During the set, singer Dave Matthews shared a message of hope for fans who felt like “the world has lost her mind” while calling out “mis-leaders.” After the performance, Matthews returned to the stage holding up a pair of signs that read “Stop killing children” and “Stop the genocide,” which he has brought out at previous events.

On the Blue Stage, former Rage Against the Machine star and Harvard alum Tom Morello was back in his old stomping grounds. During his set, Morello reminisced with the crowd about his days in Cambridge. He also welcomed them to show with a heavy dig at the Trump administration, saying, “the last big event before they throw us all in jail.” (His stage and guitar were adorned with anti-Trump and -ICE motifs.) Morello also shouted out the Springsteen-Trump feud, adding: “Bruce draws a bigger audience,” before playing the Springsteen classic “The Ghost of Tom Joad.”

Morello also paid tribute to former Audioslave bandmate Chris Cornell with a rendition of “Like a Stone,” calling it “more of a prayer than a song” while honoring the late singer. The tributes continued on the Blue Stage with Public Enemy’s Flavor Flav and Chuck D, as the duo got the crowd to shout well wishes for recovering Celtics star Jayson Tatum. Flav also paid tribute to “Cheers” actor George Wendt, who died last week, telling the audience, “we gotta pour one out for Norm.” Chuck D and Morello teamed up for a song during the evening as well.

Other highlights from day three included Sublime, with singer Jakob Nowell honoring his late dad and the band’s former singer Bradley Nowell, as Sunday marked 29 years since his death. Amid a cloudy overcast, he added: “If you’ve got a family member or loved one who isn’t here with you tonight, I just want to let you know that they are here, man, sure as that [expletive] sun’s going to come out again.” The sun ended up breaking through the clouds shortly afterwards as the band performed, with Nowell later joking, “Yeah, we planned it.”

Vampire Weekend, Remi Wolf, Spin Doctors, and more also performed on Sunday.

Check out more photos from Sunday below.

Globe correspondents Haley Clough and Marianna Orozco contributed to this report.

Matt Juul can be reached at matthew.juul@globe.com.

Boston, MA

Braintree prevails in inaugural Don Fredericks Tournament

DORCHESTER – On the day local legend Don Fredericks passed away last year, the Braintree baseball team pulled out a win in extra innings over rival Walpole in a game that felt as though the former coach was right there with the program.

It’s only fitting then for the Wamps to pull off a similar ending in the inaugural Don Fredericks Memorial Tournament’s championship game – relocated to Monan Park – Sunday afternoon.

Backed by a gritty complete game from Connor Grieve in which he stranded six base runners, Braintree (12-8) rallied from a two-run deficit by scoring a run in each of the fifth, sixth and seventh innings en route to a walk-off, 3-2 win over BC High.

Eagles (11-9) starter Hudson Verrill held the Wamps hitless for the first 4 1/3 innings, and they only had three overall. But a patient approach drew enough baserunners to give Braintree a fighting chance, and Michael Ryan hit a walk-off single in the seventh inning to deliver an emotional win.

“It’s just kind of symbolic – I don’t know if I believe a lot of that stuff, but it’s making me think about it,” said Braintree head coach Bill O’Connell. “That was an old-school, grind-it-out, gritty Braintree game. … As it got deeper into the game, and we kept it close, we felt like that’s when we’d have a chance to come back with our mental toughness and all, and they did a great job.”

The day prior, star pitcher Luke Joyce delivered a 15-strikeout masterpiece in the semifinals of the tournament – an outing O’Connell can’t speak enough about. Grieve didn’t replicate that gem, but had a major performance in its own right to earn the championship’s Danny Ventura Most Valuable Player award.

BC High racked up seven hits and a walk against him, only striking out twice. Both of the runs it scored came with two outs, using RBI singles from Wyatt Miller (2-for-4) and Jackson Richard in the third and fourth innings, respectively, to build a 2-0 lead.

Outside of those two knocks, though, Grieve consistently limited damage by throwing strikes and forcing easy outs to the defense behind him. One of his strikeouts came with two outs and two on in the third inning, and he stranded two in the sixth with one out by forcing soft contact.

Once the score was tied after six, Grieve needed just four pitches to set down BC High in the seventh.

“I just wanted to throw strikes, don’t give them anything right down the middle that they could hit in the gap,” Grieve said. “I feel like I did a really good job of just throwing strikes, attacking hitters, and making them put the ball in play. And my (defense) did a great job behind me.”

“In our program, the greatest compliment you can get is if you’re a grinder,” O’Connell added. “We’re just a bunch of hometown guys playing for their community. Connor Grieve – he’s a grinder.”

Patience proved especially important for Braintree on the offensive end, as Verrill (4 1/3 innings, no hits, four walks, one unearned run, three strikeouts) stymied the Wamps for much of the way. An error on an attempted double-play with one out in the fifth inning knocked him out of the game, and the rally began.

Sean Canavan immediately singled to load the bases, and Owen Donnelly walked in a run to cut the deficit to 2-1. BC High reliever Adam Bushley forced Ryan into a double play to preserve the lead, but Grieve led off the sixth inning with a single. Pinch-runner Max DeRoche advanced on a passed ball, and came around when the Eagles erred trying to throw him out at third on Matt Rogers’ sacrifice bunt.

Bushley stranded Rogers at third with one out, though Sean Stenmon’s walk and another Eagles miscue put runners on first and third with one out in the seventh. Ryan had one pitch to get the job done before O’Connell wanted to signal for a squeeze bunt, and he sent it to right field for the win.

“I knew we were going to stay in this game, fight back,” Grieve said. “And I had a really good feeling around the fifth, sixth inning – when we were getting guys on – that we were going to win this game. … I knew (Ryan) was going to get it done.”

The win is a big lift for Braintree, which heads into the state tournament without two of their top players in their normal roles because of injury.

But also for what it represented, in honor of Fredericks, in front of his family in attendance.

“It was emotional because Donny has meant so much to all of us,” O’Connell said. “He was such a great mentor. Not only to watch him as a coach, but when I got the job, he wrote me personal letter in pen and (paper). I still have it to this day. … This tournament is going to go along longer than any of us are coaching, we just want to kickstart it to keep his legacy and his name out there for years to come.”

“(O’Connell) told us before the tournament that the whole town expects us to win this,” Grieve added. “This was a tournament we need to win, would be a big statement going into the playoffs.”

-

Business1 week ago

Business1 week agoVideo: How Staffing Shortages Have Plagued Newark Airport

-

Movie Reviews1 week ago

Movie Reviews1 week ago‘Nouvelle Vague’ Review: Richard Linklater’s Movie About the Making of Godard’s ‘Breathless’ Is an Enchanting Ode to the Rapture of Cinema

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoSevere storms kill at least 21 across US Midwest and South

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoWatch: Chaos as Mexican Navy ship collides with Brooklyn Bridge, sailors seen dangling – Times of India

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoTexas AG Ken Paxton sued over new rule to rein in 'rogue' DAs by allowing him access to their case records

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoMaps: 3.8-Magnitude Earthquake Strikes Southern California

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoAfghan Christian pastor pleads with Trump, warns of Taliban revenge after admin revokes refugee protections

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoTrump, alongside first lady, to sign bill criminalizing revenge porn and AI deepfakes