News

Cancer interrupted their school lives, but also set them on a mission

At age 8 in 2009, EJ Beck hugs her favorite book, Laura Ingalls Wilder’s These Happy Golden Years. At 10, center, she is pictured in the hospital where she was treated for thyroid cancer. For Beck and her family, the Happy Golden Years image became emblematic of her life, before. At right, EJ Beck today is a 23-year-old medical student.

Beck family; José A. Alvarado Jr. for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Beck family; José A. Alvarado Jr. for NPR

EJ Beck was a bookish, wispy 10-year-old when a doctor found the thyroid cancer on her tiny neck that upended her life. Treatment for that cancer took Beck’s joyful school routine and replaced it with a complicated surgery, followed by a harrowing radiation treatment that made her so sick and radioactive, it required her to remain in a sealed chamber without human contact for many days.

Beck, along with her parents, had decided not to tell friends, her teachers or even her two younger sisters about her illness, hoping that might help her slip back into normal life, eventually. But in the short term, it intensified her isolation in the hospital, where she passed her solitary confinement rereading the Harry Potter series and drawing on a picture of Spiderman posted to the window.

“I was so, so jealous because Spiderman could just leave the hospital, and I couldn’t,” Beck recalls. “Spiderman got to take radiation, and he got cool powers; I got sick and sad and lonely and tired.”

Today, Beck is a 23-year-old medical student, and among a growing population of 18 million people who are surviving cancer for much longer, thanks to myriad recent advances like AI-powered tumor detection and new immunotherapies that chemically target cancers. Survival rates for pediatric cancer, in particular, are considered a crowning medical achievement: Those rates increased from 58% in the mid-1970s to 85% today.

But in order to get on with life after treatment, Beck also had to overcome many of the less-discussed aftereffects of cancer – notably the missed schooling and loss of identity and peer support that came with it, not to mention various other cognitive and physical impacts of treatment that deeply shape survivorship. Patients often feel forgotten when treatment ends, but research shows the knock-on effects, from mental health to financial challenges, can persist decades into recovery.

Out of step with peers

Today Beck is cancer-free, but says she still feels she lives in its shadow – quite literally, in the sense that her apartment is within earshot of the sirens near the New York City hospital complex where she received treatment as a child.

Also, the experience forged her into who she is, she says, and left her feeling scholastically, socially, and emotionally out of step with peers. “It takes a really long time to feel like you’re falling into sync with everybody else,” Beck says. “Even if you would make it on to college with everyone else, you kind of feel like you’re marching to a slightly different beat and you’re trying really hard to keep up.”

For many years, EJ Beck’s mother silently carried a golden ribbon that she received from the hospital to advocate for pediatric cancer awareness. “She passed the ribbon on to me,” says Beck, who has that ribbon hanging above her desk at home.

José A. Alvarado Jr. for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

José A. Alvarado Jr. for NPR

When a child is diagnosed and undergoing treatment, doctors and parents tend to pour their energies – understandably – into managing the medical demands of pediatric cancer. But Julia Gomez, an education coordinator at NYU Langone Health, says for kids, the absence of the normalcy of school usually hits harder. “It’s quite devastating, to the whole child,” she says. “School is their whole world.”

With the increase in the population of survivors, there’s growing recognition that cancer care must also include planning for various aspects of life after treatment. And Gomez says more cancer centers, especially at research hospitals, are hiring education coordinators like her, who can help patients and their families stay connected to school during treatment and transition them back into their lives afterward.

Consistent support

Gomez works with some patients for up to five years, helping them and their families navigate the dizzying number of school or state bureaucracies to ensure students receive home tutoring or additional accommodations, for example. She matches them with tutors in the hospital or at home, and keeps teachers at school updated with treatment plans – tasks parents are often too overwhelmed to manage.

“I can offer myself to take on the whole academic-education-school piece,” she says.

Patient advocates argue specialized wraparound care like education coordinators should be an essential part of all pediatric and young adult cancer treatment plans. But they realistically are only accessible to a privileged minority of patients who live near the research hospitals or cancer centers that offer them.

Aside from those outside services, family engagement and support can have huge bearing on how children fare through treatment and survivorship, says Dr. Saro Armenian, director of the Childhood, Adolescent and Young Adult Survivorship Program at City of Hope Children’s Cancer Center in Los Angeles.

The more consistent, positive support a child feels from the adults and schools around them, the better they will maintain their self-worth through the grueling times, Armenian says. “The social network plays a huge role, especially as a child, when you really don’t have a guidepost for how you should behave and act in that situation.”

But even when children can remain in class or reintegrate back into school, they often feel marked by disease.

EJ Beck, for example, typically only missed morning classes through most of her treatments, but her highly restrictive, iodine-free diet meant she couldn’t eat school lunch, making her a conspicuous target for classmates. “I had this girl — I’ll never forget it,” Beck recalls, “she’d come up to me and say, ‘You’re really bullying everyone else because you’re so skinny and you’re dieting, so you’re saying that the rest of us are fat.’”

Beck swallowed her explanation to keep her cancer secret: “Once people know, they never look at you the same way.”

Still, she felt lucky, because she didn’t lose her hair — that telltale, dreaded side effect — which meant keeping cancer secret was an option for her. “I had the privilege of somebody who…cancer was never going to be as visible on me as it is on the majority of cancer patients.”

An abrupt departure from normalcy

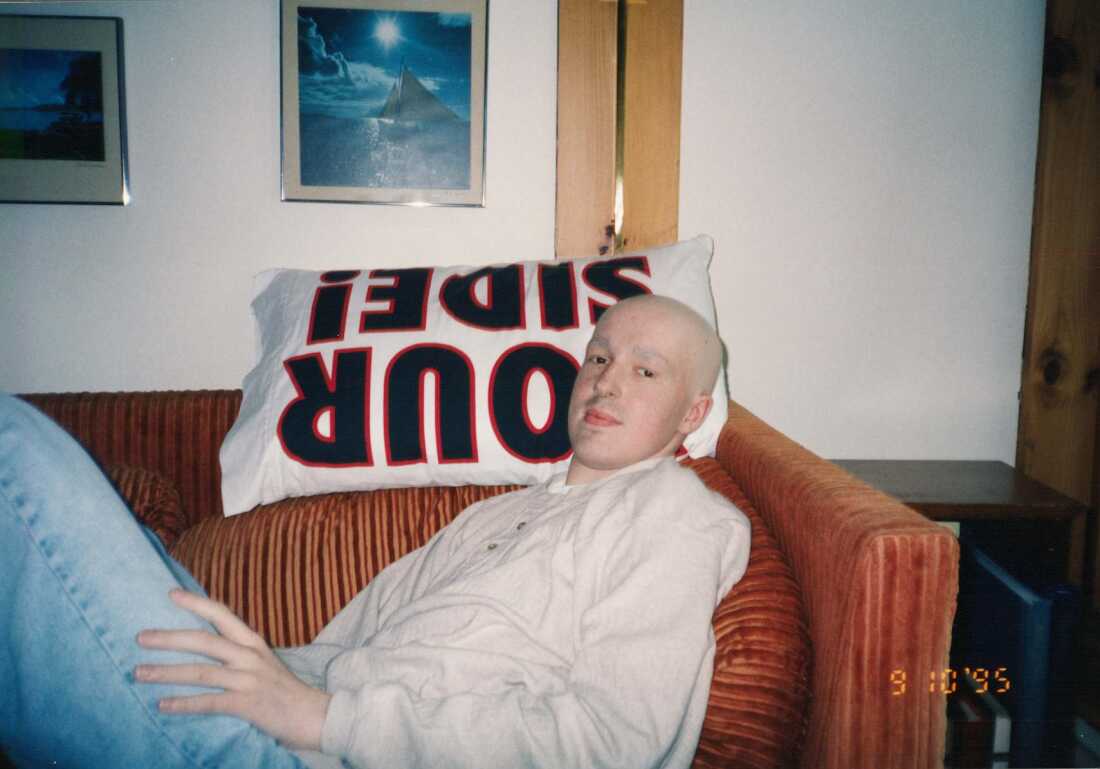

Brendan Harley’s exit from school was far more dramatic and noticeable. On the evening of May 5, 1995 – the night before his SAT exams – Harley landed in the hospital with acute leukemia at age 17.

Brendan Harley home from the hospital in September 1995 after receiving a bone marrow transplant to treat his leukemia. “I was effectively living in a bubble at home,” Harley says.

Harley family

hide caption

toggle caption

Harley family

“I had to call my date for the junior prom, which was the next weekend, and say, ‘Sorry, I’m not going to be there’ – and I was then gone,” he says. He remained in the hospital, in treatment, or in isolation and away from school and friends, for a full year. Notably, this was in an era before cell phones and social media existed, so Harley’s isolation felt complete.

“I was effectively living in a bubble at home,” Harley says. His middle brother helped ferry homework to and from school. “I’d have a tutor that showed up once a week and we would set masks and gloves on different sides of the room and talk.”

It helped Harley to keep pinning his thoughts to discrete school assignments and other tasks he could control. Bald and tired, Harley studied frantically from his hospital bed, clinging to schoolwork as a handhold on life.

Often, things didn’t go to plan, as was the case with his chemistry finals: “I got out and went right to take my exams in June and I couldn’t remember any of the things I was studying because of all the chemotherapy.”

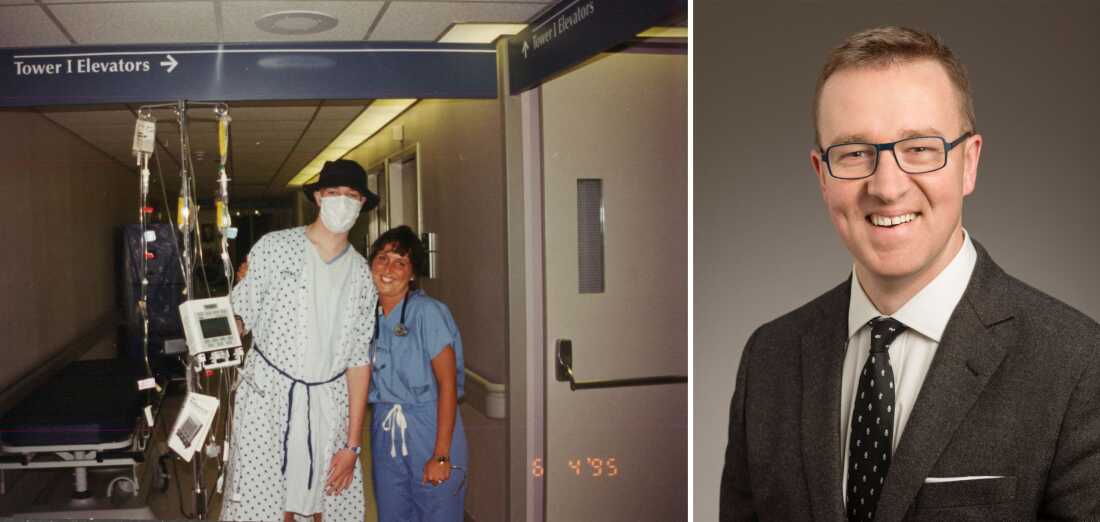

On May 5, 1995, at age 17, Brendan Harley was diagnosed with leukemia. The following day, he started chemotherapy treatments and spent a month on the oncology floor recovering at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. Now, as a biochemical engineer at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, he’s developing better tumor models that improve targeted treatments

Harley family

hide caption

toggle caption

Harley family

But, says Harley, returning home after feeling so vulnerable made him more determined to live, fully. Driving home from the hospital with the trees having reached full bloom in his absence, he appreciated the vibrancy of color with fresh eyes – and saw his own life in the same light. “It was like I saw it for the first time; I’ve made it back,” he says. “To this day, I can’t forget.”

Vocations forged by experience

Three decades later, Harley’s cancer-free and a father of two. He now fights cancer on a different front. As a biochemical engineer at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, he’s developing better tumor models that help improve targeted treatments to both kill cancer and improve the quality of life afterward. Harley says the cause of his own leukemia may be the earlier radiation and chemotherapy treatments he received at age 1, when he was diagnosed with a neuroblastoma. “How can I make it so that the next generation goes through something different?” he says of his career in cancer research.

Personalizing treatments can help avoid some of the harsher alternatives. “This idea of taking cells from a patient and turning them into a cure…that’s something that is incredibly motivating,” he says.

Meanwhile, EJ Beck is on her own revenge tour against cancer. This fall, she started medical school at NYU Langone, the very hospital where she’d received treatment as a 10 year old. Walking through the same doors as a physician in training felt like the bookend that made her whole life story make sense. “I almost feel like I can see the younger version of myself standing next to me in such a different place in her life,” Beck says.

EJ Beck is now pursuing a medical degree at the same hospital complex where she received treatment as a child. “Sometimes it feels as though I’ve lived lifetimes since then, and it hurts to think about,” she says “But mostly they just make me feel immense gratitude for where I am now – I’m incredibly blessed.”

Beck family

hide caption

toggle caption

Beck family

What cancer stole from her childhood, she’s now reclaiming. “It was extremely identity-forming to me. It helped me understand people’s pain more and gave me a mission that I’ve carried with me in life to become a physician who gives back to a field that’s given me so much.”

Original photography by José A. Alvarado Jr. Visuals design and editing by Katie Hayes Luke.

Audio and digital story edited by Diane Webber.

News

Video: F.A.A. Ignored Safety Concerns Prior to Collision Over Potomac, N.T.S.B. Says

new video loaded: F.A.A. Ignored Safety Concerns Prior to Collision Over Potomac, N.T.S.B. Says

transcript

transcript

F.A.A. Ignored Safety Concerns Prior to Collision Over Potomac, N.T.S.B. Says

The National Transportation Safety Board said that a “multitude of errors” led to the collision between a military helicopter and a commercial jet, killing 67 people last January.

-

“I imagine there will be some difficult moments today for all of us as we try to provide answers to how a multitude of errors led to this tragedy.” “We have an entire tower who took it upon themselves to try to raise concerns over and over and over and over again, only to get squashed by management and everybody above them within F.A.A. Were they set up for failure?” “They were not adequately prepared to do the jobs they were assigned to do.”

By Meg Felling

January 27, 2026

News

Families of killed men file first U.S. federal lawsuit over drug boat strikes

President Trump speaks as U.S. Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth looks on during a meeting of his Cabinet at the White House in December 2025.

Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images

Relatives of two Trinidadian men killed in an airstrike last October are suing the U.S. government for wrongful death and for carrying out extrajudicial killings.

The case, filed in Massachusetts, is the first lawsuit over the strikes to land in a U.S. federal court since the Trump administration launched a campaign to target vessels off the coast of Venezuela. The American government has carried out three dozen such strikes since September, killing more than 100 people.

Among them are Chad Joseph, 26, and Rishi Samaroo, 41, who relatives say died in what President Trump described as “a lethal kinetic strike” on Oct. 14, 2025. The president posted a short video that day on social media that shows a missile targeting a ship, which erupts in flame.

“This is killing for sport, it’s killing for theater and it’s utterly lawless,” said Baher Azmy, legal director of the Center for Constitutional Rights. “We need a court of law to rein in this administration and provide some accountability to the families.”

The White House and Pentagon justify the strikes as part of a broader push to stop the flow of illegal drugs into the U.S. The Pentagon declined to comment on the lawsuit, saying it doesn’t comment on ongoing litigation.

But the new lawsuit described Joseph and Samaroo as fishermen doing farm work in Venezuela, with no ties to the drug trade. Court papers said they were headed home to family members when the strike occurred and now are presumed dead.

Neither man “presented a concrete, specific, and imminent threat of death or serious physical injury to the United States or anyone at all, and means other than lethal force could have reasonably been employed to neutralize any lesser threat,” according to the lawsuit.

Lenore Burnley, the mother of Chad Joseph, and Sallycar Korasingh, the sister of Rishi Samaroo, are the plaintiffs in the case.

Their court papers allege violations of the Death on the High Seas Act, a 1920 law that makes the U.S. government liable if its agents engage in negligence that results in wrongful death more than 3 miles off American shores. A second claim alleges violations of the Alien Tort Statute, which allows foreign citizens to sue over human rights violations such as deaths that occurred outside an armed conflict, with no judicial process.

The American Civil Liberties Union, the Center for Constitutional Rights, and Jonathan Hafetz at Seton Hall University School of Law are representing the plaintiffs.

“In seeking justice for the senseless killing of their loved ones, our clients are bravely demanding accountability for their devastating losses and standing up against the administration’s assault on the rule of law,” said Brett Max Kaufman, senior counsel at the ACLU.

U.S. lawmakers have raised questions about the legal basis for the strikes for months but the administration has persisted.

—NPR’s Quil Lawrence contributed to this report.

News

Video: New Video Analysis Reveals Flawed and Fatal Decisions in Shooting of Pretti

new video loaded: New Video Analysis Reveals Flawed and Fatal Decisions in Shooting of Pretti

By Devon Lum, Haley Willis, Alexander Cardia, Dmitriy Khavin and Ainara Tiefenthäler

January 26, 2026

-

Sports1 week ago

Sports1 week agoMiami’s Carson Beck turns heads with stunning admission about attending classes as college athlete

-

Illinois5 days ago

Illinois5 days agoIllinois school closings tomorrow: How to check if your school is closed due to extreme cold

-

Pittsburg, PA1 week ago

Pittsburg, PA1 week agoSean McDermott Should Be Steelers Next Head Coach

-

Lifestyle1 week ago

Lifestyle1 week agoNick Fuentes & Andrew Tate Party to Kanye’s Banned ‘Heil Hitler’

-

Pennsylvania1 day ago

Pennsylvania1 day agoRare ‘avalanche’ blocks Pennsylvania road during major snowstorm

-

Sports1 week ago

Sports1 week agoMiami star throws punch at Indiana player after national championship loss

-

Cleveland, OH1 week ago

Cleveland, OH1 week agoNortheast Ohio cities dealing with rock salt shortage during peak of winter season

-

Science1 week ago

Science1 week ago‘It is scary’: Oak-killing beetle reaches Ventura County, significantly expanding range