Lifestyle

‘The Challenge’ is understanding why this ‘Squid Game’ game show was green-lit

Squid Game: The Challenge is a reality game show based on the sensational 2021 South Korean drama series. But this gruesome, creatively misbegotten concept should never have made it past the first meeting.

Netflix

hide caption

toggle caption

Netflix

Squid Game: The Challenge is a reality game show based on the sensational 2021 South Korean drama series. But this gruesome, creatively misbegotten concept should never have made it past the first meeting.

Netflix

It is one thing to extend a successful television series in a way that drains its meaning and dilutes its impact. It is another to drown it in greed and to gleefully embrace what it diagnoses as economically and spiritually catastrophic.

Squid Game, the South Korean drama series that was a sensation on Netflix in September 2021, is a work of despair. In it, hundreds of players who are deeply in debt are invited to participate in a secretive competition with an enormous cash prize for those who successfully complete a series of games. What they don’t realize until the first game is underway is that as they are eliminated from each game, they will be murdered.

The first episode, “Red Light Green Light,” finds 456 people in an enormous open space playing the childhood game in which, if you are caught moving after you’re told to freeze, you are out. But in this case, when you are out, you are shot dead by enormous guns embedded in the walls. Shot in the head, the neck, the back. As the group realizes what’s happening, many panic and run for the exit, but of course, this violates the rules as well, so they are massacred as they try to escape. They end as a pile of dead bodies against the doors, their identical green sweatsuits drenched in blood. Those who survive, owing to their desperate circumstances, eventually play on. How inhuman it is to conduct this game, to have to play it, and especially to watch it, those are the things that give the scene and the series such weight.

At some point, some person, some fool, somewhere, in some office, flush with the success of the series both critically and commercially, decided it would be entertaining to create a game show — a real game show — that imitated this scenario as closely as possible without actually murdering anyone. And so you have Squid Game: The Challenge.

What makes The Challenge so bad is that outside of the simulated killings and their shock value, it’s dull.

Netflix

hide caption

toggle caption

Netflix

It brings 456 real people to a vast dormitory designed to look as much as possible like the one in the show. And it begins, too, with the game of “Red Light Green Light.” It would have been easy to design The Challenge such that if you are caught moving, your number is called and you are simply out of the game. Had they stopped there, this effort would be empty and pointless, but perhaps only that. Instead, when a player is caught moving, a squib inside their shirt explodes, splattering their chest and neck with black fluid, and they fall over and play dead. It is meant to look as much like a true massacre by gunfire as they could manage, although someone seems to have drawn the line at fake red blood in a meaningless gesture toward, one can only assume, some simulacrum of good taste.

The original Squid Game indicts, above all, anyone who would find such a competition entertaining. The villains are the people who watch, who plan, and who enjoy this spectacle. So what makes The Challenge so creatively misbegotten is that it suggests at best (or worst?) a cynical effort to exploit the most superficial elements of Squid Game while entirely missing its point, and at worst (or best?) an ignorant failure to understand what the show is even supposed to be about. These games are not particularly exciting, in and of themselves. The murders are the story; the brutality is the one thing that makes it compelling. And the only reason the fictional game has been designed by its evil creators is that they want to watch people scramble to save their very lives. The deaths are not a decoration; they are the fabric of the thing.

And so what makes The Challenge so bad is that outside of the simulated killings and their shock value, it’s dull. There are too many contestants to get to know and no central characters to grab onto like the ones in Squid Game.

What makes The Challenge feel wrong is that a competition where the first episode is a whimsical game of “mass shooting and panic,” complete with squibs, complete with splatter, should never have made it past the very first meeting. That nobody said no, that nobody said “there’s an excellent chance that we will be dropping these episodes in the aftermath of a real mass shooting, and simulating one for entertainment will seem like an extraordinary violation of bare-bones decency” is an indictment of everyone involved. Someone — everyone — has lost the plot. (Not to mention what some contestants claim were, in real life, apparently atrocious conditions.)

Yep, this pretty much sums it up.

Pete Dadds/Netflix

hide caption

toggle caption

Pete Dadds/Netflix

Yep, this pretty much sums it up.

Pete Dadds/Netflix

In a media environment in which creative people manage, against all odds, to do work that is daring and interesting — like Squid Game was — it is brutal to see the same company that drove that work’s success turn around and treat it so carelessly. It’s not the first time Netflix has tried to have its cake and eat it too; recent seasons of Black Mirror that aired on Netflix have skewered formats and practices straight out of the service’s own playbook, to the point where a Netflix clone called Streamberry was one of the primary villains of the sixth season. But at least in that one, as far as we know, nobody got hurt.

This piece also appeared in NPR’s Pop Culture Happy Hour newsletter. Sign up for the newsletter so you don’t miss the next one, plus get weekly recommendations about what’s making us happy.

Listen to Pop Culture Happy Hour on Apple Podcasts and Spotify.

Lifestyle

Norma Swenson, ‘Our Bodies, Ourselves’ Co-Author, Dies at 93

Norma Swenson was working to educate women about childbirth, championing their right to have a say about how they delivered their babies, when she met the members of the collective that had put out the first rough version of what would become the feminist health classic “Our Bodies, Ourselves.” It was around 1970, and she recalled a few of the women attending a meeting she was holding in Newton, Mass., where she lived.

It did not go well. One of them shouted at her, “You are not a feminist, you’ll never be a feminist and you need to go to school!”

“I was stricken,” Ms. Swenson remembered in a StoryCorps interview in 2018. “But also feeling that maybe she was right. I needed to know more things.”

She did, however, know quite a bit about the medical establishment, the paternalistic and condescending behavior of male doctors — in 1960, only 6 percent of incoming medical students were female — and the harmful effect that behavior had on women’s health. She had lived it, during the birth of her daughter in 1958.

Despite the initial tension — the woman who had berated Ms. Swenson felt her activism was too polite, too old-school — the members of the Boston Women’s Health Book Collective, as they called themselves, invited Ms. Swenson to join their group. She would go on to help make “Our Bodies, Ourselves” a global best seller. It was a relationship that lasted for the next half-century.

Ms. Swenson died on May 11 at her home in Newton. She was 93.

The cause was cancer, her daughter, Sarah Swenson, said.

It was during a women’s liberation conference in Boston in 1969 that a small group began sharing stories of their fraught experiences with doctors. They told of their frustration with the sexism of the medical establishment and of how confounded they were by the lack of knowledge they had about their own bodies. So they set out to learn for themselves, and in so doing they began to assemble a candid and humane encyclopedia of women’s health — by women, for women.

In 1970, the New England Free Press published their first rough version. It was an immediate underground success, with some 225,000 copies eventually sold. The publisher couldn’t keep up with the demand.

Ms. Swenson joined the group in 1971, when commercial publishers were courting the group’s members. After Simon & Schuster published the book in 1973, much gussied up and expanded, it became a juggernaut.

It covered topics that were then considered unmentionable and, in the case of abortion, illegal: sexuality, masturbation, abortion and birth control. There were chapters on body image, rape and self-defense; on heterosexual and lesbian relationships; on childbirth and its aftermath; and, in later editions, on menopause. There were detailed illustrations — including six variations of hymens — and photographs, including a helpful how-to for viewing one’s own vagina with a mirror.

When The New York Times’s chief book critic, Christopher Lehmann-Haupt — a man! — reviewed it, he explained his rationale for giving himself the assignment.

“I learned a great deal from this book that I did not know before, or had somehow forgotten,” he wrote. “And if the authors are correct in their belief that one of the major reasons why men oppress women is because ‘of the male fear and envy of the generative and sexual powers of women’ — and I think they are — why, then, it will do no harm at all for men to read ‘Our Bodies, Ourselves’ and expend a little rational thought on these powers.”

The book revolutionized how women’s health was discussed, and it quickly became a cultural touchstone. Reading it — often under the covers — was a rite of passage for many young women, who nicked it from their mothers’ bedside tables. More progressive moms gave it to their daughters in lieu of “the talk.”

Barbara Ehrenreich called it a manifesto of medical populism. The Moral Majority deemed it obscene. It even had a cameo in “Heartburn,” Nora Ephron’s 1983 revenge novel about the breakup of her marriage.

But the book was always a labor of love. And as the royalties poured in, the Obos, as they called themselves, used the money not to pay themselves but to create a nonprofit that made small grants to women’s health groups.

In 1977, Ms. Swenson and Judy Norsigian, another core member of the collective, teamed up for a tour of 10 European countries to meet with women’s groups who were putting together their own versions of “Our Bodies, Ourselves.” Ms. Swenson would later help to oversee the international editions and adaptations, and would lecture around the world, particularly in developing countries.

“Norma was always committed to an intersectional approach,” Ms. Norsigian said. “She made sure the activism could fit people’s lifestyles. How they could do things with limited resources. How to tailor the work to specific communities in less industrialized countries. She helped breastfeeding support groups in the Philippines, for example, and met with a doctor in Bangladesh who was advocating for indigenous production of essential drugs.”

“Feminism,” Ms. Swenson once told a group of doctors, “is just another name for self-respect.”

Norma Lucille Meras was born on Feb. 2, 1932, in Exeter, N.H., the only child of Halford Meras, who owned the town’s furniture store, and Nellie (Kenick) Meras, who worked as the store’s bookkeeper.

When she was 9, the family moved to Boston. She attended the prestigious Girls’ Latin School (now Boston Latin Academy), graduating in 1949 and studied sociology at Tufts University. She graduated in 1953 and, three years later, married John Swenson, a decorated World War II pilot — he was a member of the 100th Bomb Group of the Eighth Air Force, also known as the Bloody Hundredth — who worked in insurance and for the Post Office.

It was her daughter’s birth that had made Ms. Swenson an activist. She wanted to deliver the baby naturally, without medication. Her decision was such an anomaly that residents at the Boston Lying-In Hospital gathered to watch her labor. It went swimmingly.

But Ms. Swenson, who was in a 12-bed ward, was surrounded by women who were suffering. They were giving birth according to the practices of the era: with a dose of Scopolamine, a drug that induced so-called twilight sleep and hallucinations, followed by a shot of Demerol, an opioid.

She remembered the women screaming, trying to climb out of their beds, calling for their mothers and cursing their husbands before being knocked out by the Demerol, their babies delivered by forceps.

It was barbaric, she thought. “These women weren’t being helped,” she said in 2018, “they were being controlled.”

She became president of the Boston Association for Childbirth Education, which focused on natural childbirth, in 1964, and later served as president of the International Childbirth Education Association. She earned a master’s degree in public health from Harvard in 1973.

Mr. Swenson died in 2002. Ms. Swenson’s partner for the next decade and a half, Leonard van Gaasbeek, died in 2019. Her daughter is her only immediate survivor.

For most of her life, Ms. Swenson traveled the world as an expert on reproductive rights and women’s and children’s health, advising women’s health groups and helping to connect them with policy and grant makers. She taught at the Harvard School of Public Health and served as a consultant to the World Health Organization and other groups.

“Our Bodies, Ourselves,” last updated in 2011, has sold more than four million copies and been translated into 34 languages. The nonprofit behind the book, which provides health resources to women, is now based at Suffolk University in Boston.

“It’s not that things have so dramatically improved for women,” Ms. Swenson told The Times in 1985. “But they’d be much worse if it were not for the pressure of the women’s health movement. We are a presence now that cannot be made to disappear.”

She continued: “Women’s voices are being heard, speaking about their needs and their experiences, and they are not going along with having decisions based simply on what the medical profession needs or what the drug industry needs. I find that enormously exciting.”

Lifestyle

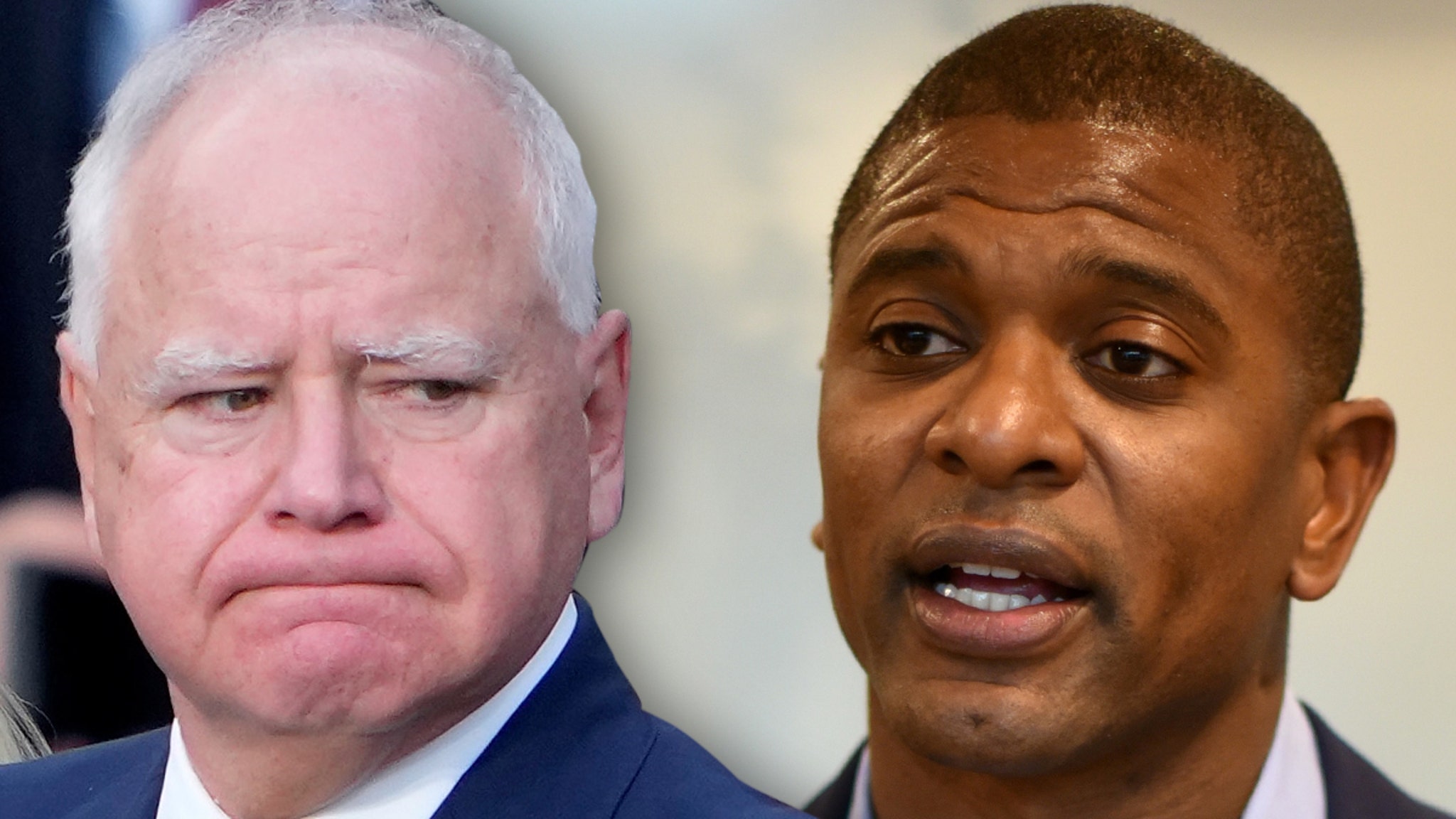

Tim Walz Allowed Minnesota to Become 'Capital of Chaos,' Former Vikings Star Says

Ex-Vikings Star

Minnesota’s The ‘Capital of Chaos’

… I Blame Tim Walz!!!

Published

A former NFL star is blaming Minnesota Governor Tim Walz for allowing chaos to reign in his state … just after two local lawmakers were shot.

Jack Brewer — a four-year player in the league who played two seasons with the Minnesota Vikings — spoke to Fox News Digital about the current state of Minnesota … and, he called it the “Capital of Chaos in America.”

Brewer says it breaks his heart to see the demise of one of the nation’s great states, adding he lived there a long time between going to school at the University of Minnesota and playing for the Vikings … and, he says it wasn’t always this dangerous.

Brewer says Governor Walz and the state’s attorney general, Keith Ellison, have allowed the “liberal hub around Minneapolis and St. Paul” to take over … which is why he thinks the state isn’t what it used to be.

Then, Brewer got a little personal … telling the outlet, “Tim Walz is the example of a weak, emasculated leader. That is not what God made fathers to be. It’s pathetic.”

As you know … law enforcement officers are still searching for Vance Boelter after Assemblywoman Melissa Hortman and State Senator John Hoffman were shot multiple times.

Hortman and her husband, Mark, were both killed while Hoffman and his wife, Yvette, were rushed to the hospital for surgery. They’re in stable condition and recovering.

Vance’s car was discovered 50 miles southwest of Minneapolis — the shooting occurred in two separate suburbs of the city — on Sunday morning. The FBI is offering a $50K reward for information leading to Boelter’s arrest and conviction.

Lifestyle

'Wait Wait' for June 14, 2025: With Not My Job guest Chris Perfetti

Chris Perfetti attends as BBC Studios Los Angeles Productions celebrates 27 Emmy nominations at the BAFTA TV Tea Party at The Maybourne Beverly Hills on September 14, 2024 in Beverly Hills, California. (Photo by Rodin Eckenroth/Getty Images for BBC Studios)

Rodin Eckenroth/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Rodin Eckenroth/Getty Images

This week’s show was recorded in Chicago with guest host Negin Farsad, judge and scorekeeper Bill Kurtis, Not My Job guest Chris Perfetti and panelists Joyelle Nicole Johnson, Alonzo Bodden, and Luke Burbank. Click the audio link above to hear the whole show.

Who’s Bill This Time

Birthday Twins In DC; The Marlboro Man Returns; Getting Your Money’s Worth From Beyonce

Panel Questions

Real ID or Real Bargains?

Bluff The Listener

Our panelists tell three stories of how people’s parents met, only one of which is true.

Not My Job: Abbott Elementary’s Christ Perfetti answers our questions about monks

Chris Perfetti, one of the stars of Abbott Elementary plays our game called, “Abbott Elementary meet the Elementary Abbotts” Three questions about monks.

Panel Questions

Family Time Just Got Easier and Messier; Best Way To Leave A Wedding

Limericks

Bill Kurtis reads three news-related limericks: Still or Sparking or Super Fancy?; A Lovable Loaf; Dating on A Budget

Lightning Fill In The Blank

All the news we couldn’t fit anywhere else

Predictions

Our panelists predict, after the big parades in Washington DC this weekend, what will be the next big parade.

-

West1 week ago

West1 week agoBattle over Space Command HQ location heats up as lawmakers press new Air Force secretary

-

Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoiFixit says the Switch 2 is even harder to repair than the original

-

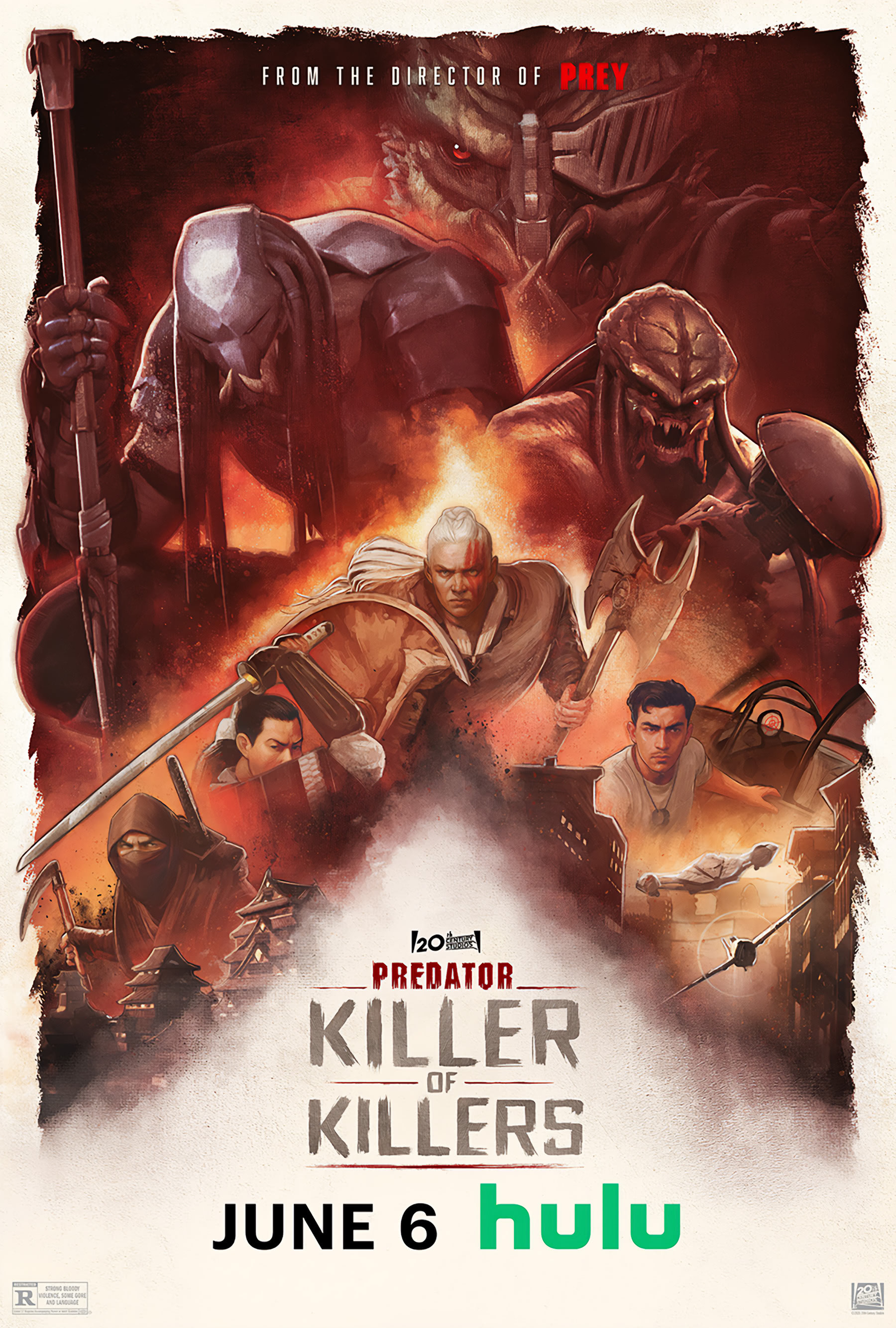

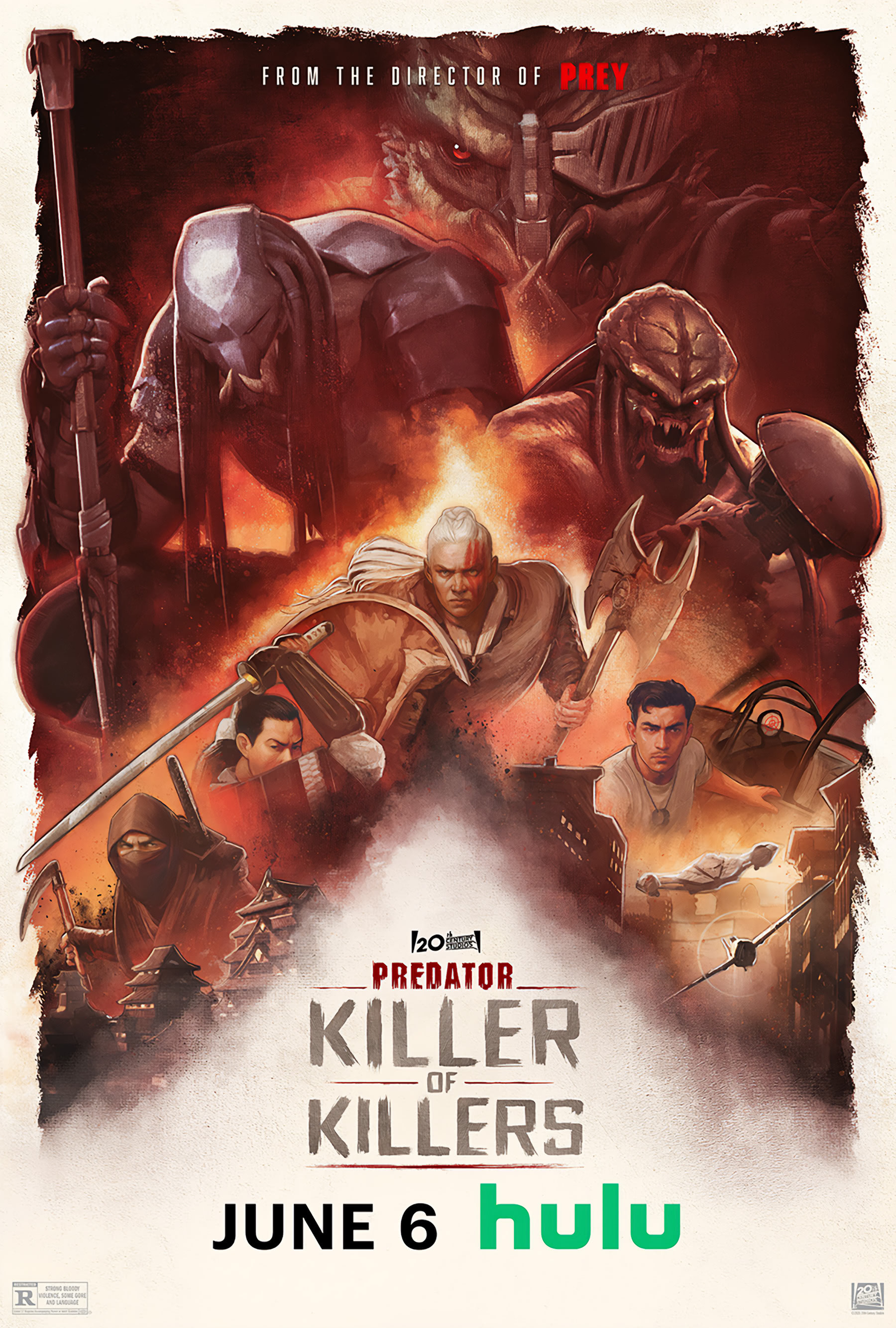

Movie Reviews1 week ago

Movie Reviews1 week agoPredator: Killer of Killers (2025) Movie Review | FlickDirect

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoA History of Trump and Elon Musk's Relationship in their Own Words

-

Finance1 week ago

Finance1 week agoChinese lenders among top backers of “forest-risk” firms

-

Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoThere are only two commissioners left at the FCC

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoA former police chief who escaped from an Arkansas prison is captured

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoUkraine: Kharkiv hit by massive Russian aerial attack