Lifestyle

Silent boy summer: Three months, no talking. Here’s how one L.A. resident did it

On a recent Monday in August, Kevito Clark hosted a video conference call to discuss the next installment of a game night he runs at the LINE LA, a hotel in Koreatown. But over the course of the hour-long meeting, he never said a word.

Instead Clark, who has a shaved head and a full beard with a touch of gray in it, used other communication tools. When the hotel’s brand manager expressed hesitation around passing out rubber bracelets, he nodded. When a collaborator mentioned the name of a tentative performer, he used Google Meet’s settings to send heart and thumbs up emojis. In between these interactions, he typed his thoughts — “Branded cups are cute,” “Any last questions?” — into the chat. Not once did he make his voice heard.

It was an unusual way to run a meeting, but Clark’s collaborators have grown accustomed to it. As he reminded the group before the call began, he is currently living out a three month vow of silence.

Across religions, vows of silence are used to quiet the mind, develop self-knowledge and connect more deeply with the divine. They tend to conjure images of monks meditating in the mountains or ascetics living in desert caves. Clark, who is 41 and lives in Leimert Park, has added a modern-day twist to the practice. Throughout the duration of his vow, which began on June 1, he has continued to live his everyday life, throwing parties, volunteering, attending concerts and even going on the occasional date.

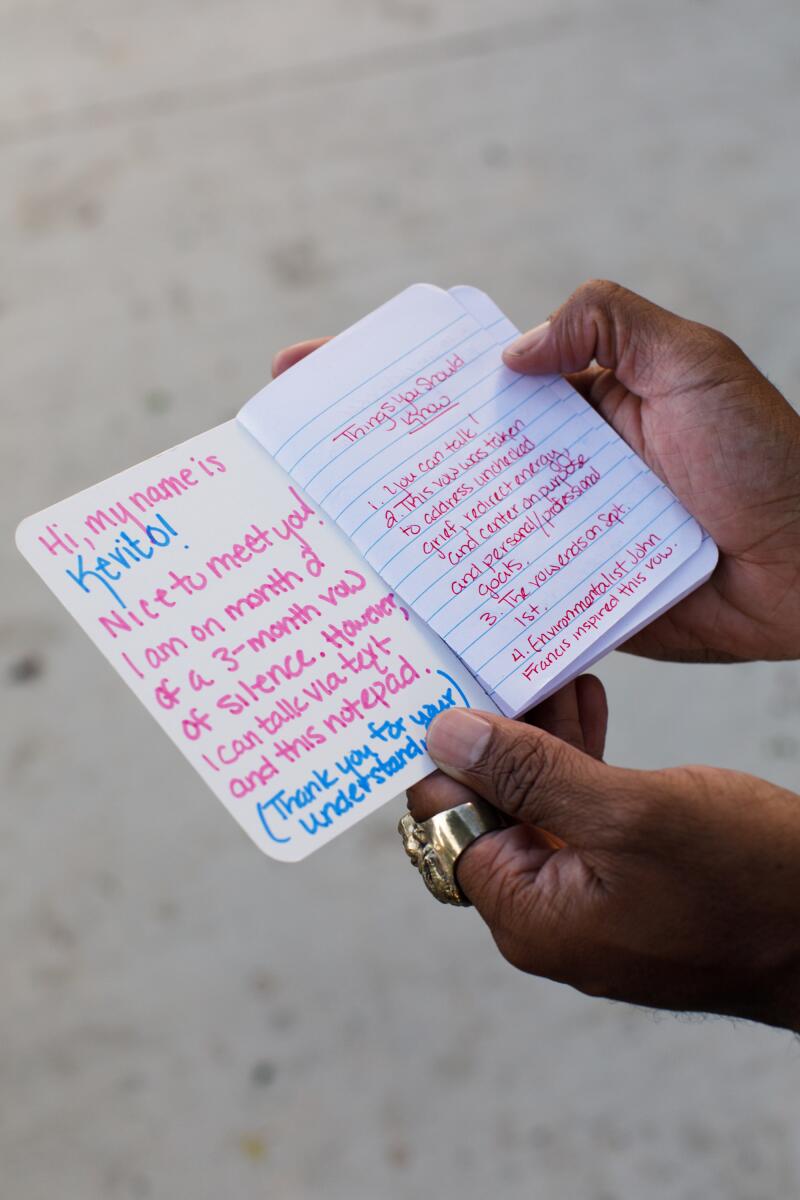

His is a vow of silence that applies only to speaking, which means he’s still texting, emailing and typing into the chat on video calls. In person, he communicates by typing messages into the iMessage app on his phone or writing in one of the pocket-sized notebooks he takes with him everywhere.

“As the saying goes, ‘What you don’t change, you choose.’ This vow was for me to grow, not for views or likes.”

— Leimert Park resident and entrepreneur Kevito Clark on his three-month vow of silence

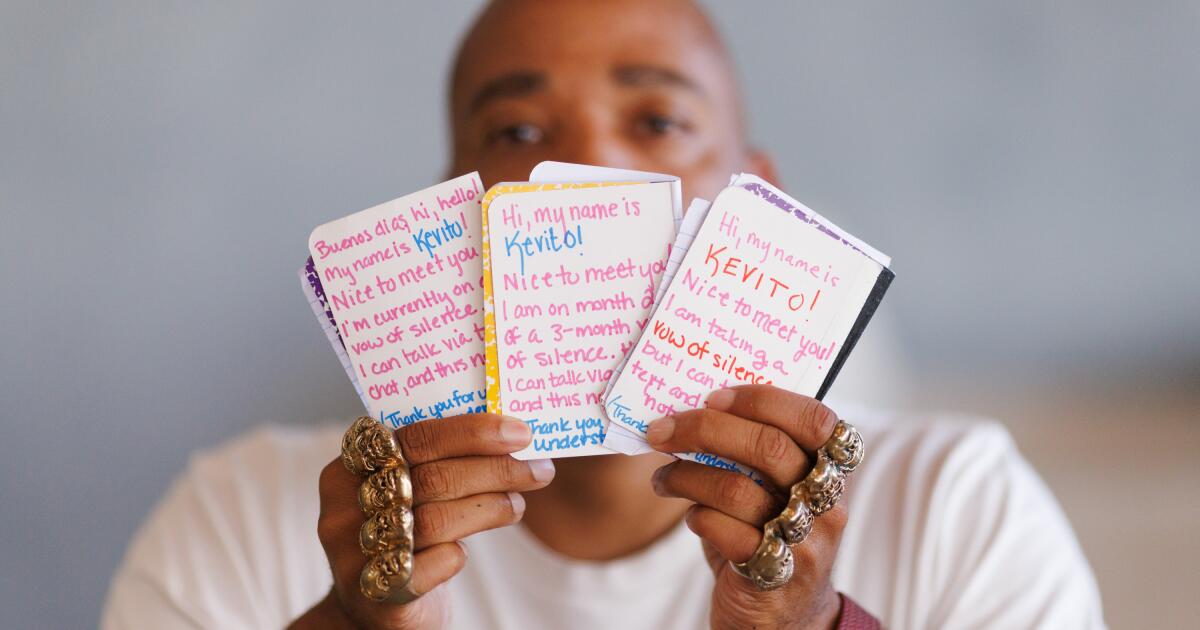

When he’s out in public he wears a red and blue button that reads: “Silent By Choice. Thanks for your understanding. I can talk via Text notes.” A similar message is written in marker on the front page of each of his notepads:

“Buenos Dias! Hi! Hello! My name is Kevito! Nice to meet you. I’m currently on a vow of silence. I can talk via text, chat, and this notepad. (Thanks for your understanding!)

Clark wears a pin that states “silent by choice,” while practicing his vow of silence. (Carlin Stiehl / For the Times)

Kevito Clark holds a notepad he uses to communicate with people that has pre-written pages explaining why he’s chosen not to speak for three months.

On the following pages he keeps pre-written answers to four questions he’s most frequently asked:

- You can talk!

- This was taken to address unchecked grief, redirect energy and center on my purpose and personal/professional goals.

- The vow ends Sept. 1, 2024.

- Environmentalist John Francis inspired this vow.

Clark, who arrived in L.A. in 2022 by way of New York and Ohio, has built his life on the power of intention. His decision to go quiet in an era where so many people spend their free time speaking to front-facing phone cameras, and in a city where the squeakiest wheels get the grease, is in service of his broader ambitions. Before his vow started, he was living out what he calls “444,” which is shorthand for his aim to consistently engage with “four acts of volunteering, four acts of self-care and four ways to show up and show out for others.” His recent vow has allowed him to commit more firmly to this goal.

“As the saying goes, ‘What you don’t change, you choose,’ ” he wrote. “This vow was for me to grow, not for views or likes.”

Still, it hasn’t always been easy to integrate silence into his day-to-day schedule. Clark often works in positions where the word “communication” is in his job title. He’s the founder and chief creative officer of Love, Peace & Spades which has a monthly residency at the LINE LA, and he currently does event services for a security company and serves as a community liaison for the non-profit Black Men Hike, all while refraining from speech.

There have been business owners and collaborators who said they wouldn’t work with him until his vow is finished. And while he had fun taking a date on a choose-your-own adventure experience through Mickalene Thomas’ All About Love exhibit at the Broad, she said she would only see him again when she could hear his voice.

Kevito Clark uses a notepad to communicate with Kimoni Oliver, a barista at ORA.

Kevito Clark walks through the streets of Leimert Park.

“I experienced how people will come to their conclusions, make assumptions (e.g., believe I have a disability),” he wrote in an email. “It takes a lot of work, patience, understanding and agreement by all parties for it to happen.”

There is no single reason that Clark took his three-month vow of silence, instead, he says a series of events catalyzed the decision. His kidneys failed in 2012 and he waited six years for a new one before a friend stepped up with a donation in 2018. Earlier this year, he mourned the back-to-back losses of two longtime friends and mentors who were like second parents to him. In the wake of their passings and the ensuing anniversaries of the deaths of other people he loved, he realized that he hadn’t made time to honor life’s transitions.

He started to ask himself, “Who are you when no one is looking?” He wondered if taking a vow of silence might provide an answer.

“It appeared like a whisper,” he wrote. “And the whisper grew into a voice.”

Online research led him to the story of John Francis, a Black environmentalist who stopped talking and riding in motorized vehicles for 17 years after witnessing two oil tankers collide and dump half a million gallons of oil into the San Francisco Bay in 1971. In a popular Ted Talk, Francis said when he decided to stop talking he found he was better able to hear others — rather than formulating a response while they were talking.

“It was a very moving experience,” Francis says in the talk. “For the first time in a long time, I began listening.”

Clark was inspired by his story. “In him I saw someone who was not only curious about himself but about how to implement positive change through discipline and facing adversity,” Clark wrote.

At the end of April, Clark began to formulate a plan to take his own, much shorter vow of silence.

He chose the time period of June 1 to Sept. 1 for his vow after reading that it takes 21 days to break habits and 30 days to begin new habits. He crafted an email explaining his decision and sent it to friends, family and collaborators describing what he was about to embark on. He could still communicate, he wrote, but only through non-speaking platforms like Google Meet, mobile text and handwritten notes.

Friends and collaborators were mostly supportive and intrigued.

“He’s a laid back, calm, cool collected dude,” said Courtney La Prince, a digital designer who met Clark while volunteering at Love, Peace & Spades. “He is really careful with his words, so when he said he was going to take a vow of silence it wasn’t hard for me to imagine.”

It has also been an adjustment for those he regularly interacts with. Conversations move at a different pace when one person is typing out their responses.

“I’ve found I need to be stationary when I talk to him,” said Kelli Boyt, who also goes by DJ Kaaos Jones. “I do a lot of my calls from the car, but I need to be in tune with whatever conversation we’re having on text messages, so I almost have to plan it out. So I’ll be in the office or sitting still in my car in the parking lot.”

Kevito Clark at ORA in Leimert Park.

Jennie Wright, regional brand manager at the LINE LA where Clark hosts Love, Peace & Spades was initially worried about the logistical implications of his vow. She and Clark grew the event together and she didn’t know how he would run it if he couldn’t talk. At the same time, she wanted to respect his decision to focus on himself.

“He took this vow of silence to center himself and find some peace within himself, so I was like, ‘Let me take my selfishness back,’ ” she said.

Over the past three months she discovered that throwing events with a silent partner isn’t as difficult as she thought.

“We’ve continued to have Love, Peace & Spades from June and they have all run successfully,” she said. “And it pushed me to step up and become more of a leader.”

As Clark approaches the end of the vow on Sept. 1, he reflected on its impact in a written interview.

“I learned to temper my thoughts, embrace gratefulness, give myself grace, pour into myself to be available for others and magnetize the positive into manifested results,” he wrote.

Still, he’s looking forward to it ending. Love, Peace & Spades is hosting its first culture and games fest on Sept. 21. He can’t wait to talk at the event. But looking back at the past three months, he said his silent vow felt more freeing than restrictive.

“I hugged deeply. I laughed heartily,” he wrote in a Zoom chat. “Those are sincere ways to communicate whether you’re speaking or not.”

Lifestyle

‘The Fall and Rise of Reggie Dinkins’ falls before it rises — but then it soars

Tracy Morgan, left, and Daniel Radcliffe star in The Fall and Rise of Reggie Dinkins.

Scott Gries/NBC

hide caption

toggle caption

Scott Gries/NBC

Tracy Morgan, as a presence, as a persona, bends the rules of comedy spacetime around him.

Consider: He’s constitutionally incapable of tossing off a joke or an aside, because he never simply delivers a line when he can declaim it instead. He can’t help but occupy the center of any given scene he’s in — his abiding, essential weirdness inevitably pulls focus. Perhaps most mystifying to comedy nerds is the way he can take a breath in the middle of a punchline and still, somehow, land it.

That? Should be impossible. Comedy depends on, is entirely a function of, timing; jokes are delicate constructs of rhythms that take time and practice to beat into shape for maximum efficiency. But never mind that. Give this guy a non-sequitur, the nonner the better, and he’ll shout that sucker at the top of his fool lungs, and absolutely kill, every time.

Well. Not every time, and not everywhere. Because Tracy Morgan is a puzzle piece so oddly shaped he won’t fit into just any world. In fact, the only way he works is if you take the time and effort to assiduously build the entire puzzle around him.

Thankfully, the makers of his new series, The Fall and Rise of Reggie Dinkins, understand that very specific assignment. They’ve built the show around Morgan’s signature profile and paired him with an hugely unlikely comedy partner (Daniel Radcliffe).

The co-creators/co-showrunners are Robert Carlock, who was one of the showrunners on 30 Rock and co-created The Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt, and Sam Means, who also worked on Girls5eva with Carlock and has written for 30 Rock and Kimmy Schmidt.

These guys know exactly what Morgan can do, even if 30 Rock relegated him to function as a kind of comedy bomb-thrower. He’d enter a scene, lob a few loud, puzzling, hilarious references that would blow up the situation onscreen, and promptly peace out through the smoke and ash left in his wake.

That can’t happen on Reggie Dinkins, as Tracy is the center of both the show, and the show-within-the-show. He plays a former NFL star disgraced by a gambling scandal who’s determined to redeem himself in the public eye. He brings in an Oscar-winning documentarian Arthur Tobin (Radcliffe) to make a movie about him and his current life.

Tobin, however, is determined to create an authentic portrait of a fallen hero, and keeps goading Dinkins to express remorse — or anything at all besides canned, feel-good platitudes. He embeds himself in Dinkins’ palatial New Jersey mansion, alongside Dinkins’ fiancée Brina (Precious Way), teenage son Carmelo (Jalyn Hall) and his former teammate Rusty (Bobby Moynihan), who lives in the basement.

If you’re thinking this means Reggie Dinkins is a show satirizing the recent rise of toothless, self-flattering documentaries about athletes and performers produced in collaboration with their subjects, you’re half-right. The show feints at that tension with some clever bits over the course of the season, but it’s never allowed to develop into a central, overarching conflict, because the show’s more interested in the affinity between Dinkins and Tobin.

Tobin, it turns out, is dealing with his own public disgrace — his emotional breakdown on the set of a blockbuster movie he was directing has gone viral — and the show becomes about exploring what these two damaged men can learn from each other.

On paper, sure: It’s an oil-and-water mixture: Dinkins (loud, rich, American, Black) and Tobin (uptight, pretentious, British, practically translucent). Morgan’s in his element, and if you’re not already aware of what a funny performer Radcliffe can be, check him out on the late lamented Miracle Workers.

Whenever these two characters are firing fusillades of jokes at each other, the series sings. But, especially in the early going, the showrunners seem determined to put Morgan and Radcliffe together in quieter, more heartfelt scenes that don’t quite work. It’s too reductive to presume this is because Morgan is a comedian and Radcliffe is an actor, but it’s hard to deny that they’re coming at those moments from radically different places, and seem to be directing their energies past each other in ways that never quite manage to connect.

Precious Way as Brina.

Scott Gries/NBC

hide caption

toggle caption

Scott Gries/NBC

It’s one reason the show flounders out of the gate, as typical pilot problems pile up — every secondary character gets introduced in a hurry and assigned a defining characteristic: Brina (the influencer), Rusty (the loser), Carmelo (the TV teen). It takes a bit too long for even the great Erika Alexander, who plays Dinkins’ ex-wife and current manager Monica, to get something to play besides the uber-competent, work-addicted businesswoman.

But then, there are the jokes. My god, these jokes.

Reggie Dinkins, like 30 Rock and Kimmy Schmidt before it, is a joke machine, firing off bit after bit after bit. But where those shows were only too happy to exist as high-key joke-engines first, and character comedies second, Dinkins is operating in a slightly lower register. It’s deliberately pitched to feel a bit more grounded, a bit less frenetic. (To be fair: Every show in the history of the medium can be categorized as more grounded and less frenetic than 30 Rock and Kimmy Schmidt — but Reggie Dinkins expressly shares those series’ comedic approach, if not their specific joke density.)

While the hit rate of Reggie Dinkins‘ jokes never achieves 30 Rock status, rest assured that in episodes coming later in the season it comfortably hovers at Kimmy Schmidt level. Which is to say: Two or three times an episode, you will encounter a joke that is so perfect, so pure, so diamond-hard that you will wonder how it has taken human civilization until 2026 Common Era to discover it.

And that’s the key — they feel discovered. The jokes I’m talking about don’t seem painstakingly wrought, though of course they were. No, they feel like they have always been there, beneath the earth, biding their time, just waiting to be found. (Here, you no doubt will be expecting me to provide some examples. Well, I’m not gonna. It’s not a critic’s job to spoil jokes this good by busting them out in some lousy review. Just watch the damn show to experience them as you’re meant to; you’ll know which ones I’m talking about.)

Now, let’s you and I talk about Bobby Moynihan.

As Rusty, Dinkins’ devoted ex-teammate who lives in the basement, Moynihan could have easily contented himself to play Pathetic Guy™ and leave it at that. Instead, he invests Rusty with such depths of earnest, deeply felt, improbably sunny emotions that he solidifies his position as show MVP with every word, every gesture, every expression. The guy can shuffle into the far background of a shot eating cereal and get a laugh, which is to say: He can be literally out-of-focus and still steal focus.

Which is why it doesn’t matter, in the end, that the locus of Reggie Dinkins‘ comedic energy isn’t found precisely where the show’s premise (Tracy Morgan! Daniel Radcliffe! Imagine the chemistry!) would have you believe it to be. This is a very, very funny — frequently hilarious — series that prizes well-written, well-timed, well-delivered jokes, and that knows how to use its actors to serve them up in the best way possible. And once it shakes off a few early stumbles and gets out of its own way, it does that better than any show on television.

This piece also appeared in NPR’s Pop Culture Happy Hour newsletter. Sign up for the newsletter so you don’t miss the next one, plus get weekly recommendations about what’s making us happy.

Listen to Pop Culture Happy Hour on Apple Podcasts and Spotify.

Lifestyle

How to have the best Sunday in L.A., according to Andy Richter

Andy Richter has found his place.

The Chicago area native previously lived in New York — where he first found fame as Conan O’Brien’s sidekick on “Late Night” — before moving to Los Angeles in 2001. Three years ago, he moved to Pasadena. “Now that I live here, I would not live anywhere else,” he says.

There are some practical benefits to the city. “I am such a crabby old man now, but it’s like, there’s parking, you can park when we have to go out,” Richter says. “The notion of going to dinner in Santa Monica just feels like having nails shoved into my feet.”

In Sunday Funday, L.A. people give us a play-by-play of their ideal Sunday around town. Find ideas and inspiration on where to go, what to eat and how to enjoy life on the weekends.

But he mostly appreciates that Pasadena is “a very diverse town and just a beautiful town,” he says.

For Richter, most Sundays revolve around his family. In 2023, the comedian and actor married creative executive Jennifer Herrera and adopted her young daughter, Cornelia. (He also has two children in their 20s, William and Mercy, from his previous marriage.)

Additionally, he’s been giving his body time to recover. Richter spent last fall training and competing on the 34th season of “Dancing With the Stars.” And though he had no prior dancing experience, he won over the show’s fan base with his kindness and dedication, making it to the competition’s ninth week.

He hosts the weekly show “The Three Questions” on O’Brien’s Team Coco podcast network and still appears in films and TV shows. “I’m just taking meetings and auditioning like every other late 50s white comedy guy in L.A., sitting around waiting for the phone to ring.”

This interview has been lightly edited and condensed for length and clarity.

7:30 a.m.: Early rising

It’s hard for me at this advanced age to sleep much past 7:30. I have a 5 1/2-year-old, and hopefully she’ll sleep in a little bit longer so my wife and I can talk and snuggle and look at our phones at opposite ends of the bed, like everybody.

Then the dogs need to be walked. I have two dogs: a 120-pound Great Pyrenees-Border Collie-German Shepherd mix, and then at the other end of the spectrum, a seven-pound poodle mix. We were a blended dog family. When my wife and I met, I had the big dog and she had a little dog. Her first dog actually has passed, but we like that dynamic. You get kind of the best of both worlds.

8 a.m.: Breakfast at a classic diner

Then it would probably be breakfast at Shakers, which is in South Pasadena. It’s one of our favorite places. We’re kind of regulars there, and my daughter loves it. It’s easy with a 5-year-old, you’ve got to do what they want. They’re terrorists that way, especially when it comes to cuisine.

I’ve lived in Pasadena for about three years now, but I have been going to Shakers for a long time because I have a database of all the best diners in the Los Angeles metropolitan area committed to memory. There’s just something about the continuity of them that makes me feel like the world isn’t on fire. And because of L.A.’s moderate climate, the ones here stay the way they are; whereas if you get 18 feet of winter snow, you tend to wear down the diner floor, seats, everything.

So there’s a lot of really great old places that stay the same. And then there are tragic losses. There’s been some noise that Shakers is going to turn into some kind of condo development. I think that people would probably riot. They would be elderly people rioting, but they would still riot.

11 a.m.: Sandy paws

My in-laws live down in Long Beach, so after breakfast we might take the dogs down to Long Beach. There’s this dog beach there, Rosie’s Beach. I have never seen a fight there between dogs. They’re all just so happy to be out and off-leash, with an ocean and sand right there. You get a contact high from the canine joy.

1 p.m.: Lunch in Belmont Shore

That would take us to lunchtime and we’ll go somewhere down there. There’s this place, L’Antica Pizzeria Da Michele, in Belmont Shore. It’s fantastic for some pizza with grandma and grandpa. It’s originally from Naples. There’s also one in Hollywood where Cafe Des Artistes used to be on that weird little side street.

4 p.m.: Sunset at the gardens

We’d take grandma and grandpa home, drop the dogs off. We’d go to the Huntington and stay a couple of hours until sunset. The Japanese garden is pretty mind-blowing. You feel like you’re on the set of “Shogun.”

The main thing that I love about it is the changing of ecospheres as you walk through it. Living in the area, I drive by it a thousand times and then I remember, “Oh yeah, there’s a rainforest in here. There’s thick stands of bamboo forest that look like Vietnam.” It’s beautiful. With all three of my kids, I have spent a lot of time there.

6:30 p.m.: Mall of America

After sundown, we will go to what seems to be the only thriving mall in America — [the Shops at] Santa Anita. We are suckers for Din Tai Fung. My 24-year-old son, who’s kind of a food snob, is like, “There’s a hundred places that are better and cheaper within five minutes of there in the San Gabriel Valley.” And we’re like, “Yeah, but this is at the mall.” It’s really easy. Also, my wife is a vegetarian, and a lot of the more authentic places, there’s pork in the air. It’s really hard to find vegetarian stuff.

We have a whole system with Din Tai Fung now, which is logging in on the wait list while we’re still on the highway, or ordering takeout. There’s plenty of places in the mall with tables, you can just sit down and have your own little feast there.

There’s also a Dave & Buster’s. If you want sensory overload, you can go in there and get a big, big booze drink while you’re playing Skee-Ball with your kid.

9 p.m.: Head to bed ASAP

I am very lucky in that I’m a very good sleeper and the few times in my life when I do experience insomnia, it’s infuriating to me because I am spoiled, basically. When you’ve got a 5 1/2-year-old, there’s no real wind down. It’s just negotiations to get her into bed and to sleep as quickly as possible, so we can all pass out.

Lifestyle

Video: Prada Peels Back the Layers at Milan Fashion Week

new video loaded: Prada Peels Back the Layers at Milan Fashion Week

By Chevaz Clarke and Daniel Fetherston

February 27, 2026

-

World3 days ago

World3 days agoExclusive: DeepSeek withholds latest AI model from US chipmakers including Nvidia, sources say

-

Massachusetts3 days ago

Massachusetts3 days agoMother and daughter injured in Taunton house explosion

-

Montana1 week ago

Montana1 week ago2026 MHSA Montana Wrestling State Championship Brackets And Results – FloWrestling

-

Louisiana6 days ago

Louisiana6 days agoWildfire near Gum Swamp Road in Livingston Parish now under control; more than 200 acres burned

-

Denver, CO3 days ago

Denver, CO3 days ago10 acres charred, 5 injured in Thornton grass fire, evacuation orders lifted

-

Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoYouTube TV billing scam emails are hitting inboxes

-

Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoStellantis is in a crisis of its own making

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoOpenAI didn’t contact police despite employees flagging mass shooter’s concerning chatbot interactions: REPORT