Lifestyle

Patching With Olivier Theyskens

This text is a part of a collection analyzing Accountable Trend and progressive efforts to handle points going through the style trade.

PARIS — The Belgian designer Olivier Theyskens could also be style’s best hoarder. For years — since his artwork faculty days in Brussels within the mid-Nineteen Nineties — he has stored almost the entire cloth swatches he has ordered. “1000’s and 1000’s,” he stated in his courtyard atelier of a regal Seventeenth-century Paris mansion on a scorching afternoon.

He wasn’t kidding. Within the entrance corridor, cardboard packing containers overflowed with swatches. Within the again, cupboard drawers erupted with extra, sorted by colour and texture — black crepes in a single; pink laces in one other. Alongside the partitions and within the corners, skinny bolts of fabric — leftovers, or “deadstock,” from earlier collections — had been piled up. In every single place one seemed, there was cloth.

“I stored them as a result of I favored them,” he stated.

He doesn’t similar to them. He’s utilizing them to make one-of-a-kind patchwork robes, jackets and tunics for personal purchasers — a kind of scrap couture that’s probably the chicest instance of upcycling and gradual style immediately. Mr. Theyskens not solely make the garments, however he additionally makes the material, stitching the swatches on the bias into a material that recollects Picasso’s harlequins. It might probably take a number of weeks to get the material laid out as he needs, and one other few weeks to make the garment; costs run as excessive as $25,000 apiece.

It’s fairly an about-face for designer who was as soon as the celebrity head of a few of style’s greatest manufacturers.

Mr. Theyskens’s pivot got here throughout the coronavirus pandemic, when the style trade was affected by an existential disaster. In Could 2020 greater than 500 designers, chief executives and retailers signed an open letter stating that they wished to make the enterprise “extra environmentally and socially sustainable” by decreasing output, waste and journey. Alessandro Michele, the inventive director of Gucci, declared that he was shifting towards a seasonless manufacturing schedule to decrease the model’s carbon footprint.

“Our reckless actions have burned the home we stay in,” he wrote in his lockdown diary, which he made public.

Mr. Theyskens had a protracted suppose, too, about how you can make style extra sustainable, and he realized the reply was his cloth stash. “I wished to provide garments with out creating waste, and optimize what we have now right here,” he stated. “There may be worth to those supplies.”

After a lot experimentation, he invented an novel course of: He sews the scraps collectively into patchwork material that he treats with warmth to create a crinkle impact, like Fortuny pleats, after which makes use of the brand new material to style garments. The mannequin Karlie Kloss walked to the Barnard Faculty gala in Manhattan in April sporting a Theyskens maxi-dress in an interesting assemblage of blues, turquoises, violets and laces, like a stained-glass window, and she or he was snapped by paparazzi alongside the best way.

“It’s an actual evolutive factor,” Mr. Theyskens stated. “And it has limitless prospects.”

Mr. Theyskens wasn’t at all times so green-minded. For almost 20 years, he was an “It” designer, recognized for dressing celebrities in his ethereal neo-Gothic silhouettes. He was thrust onto the worldwide style scene in 1998, a yr after he dropped out of faculty and began his enterprise, when the Hollywood stylist Arianne Phillips put her shopper Madonna in one among his satin coatdress ball robes for the Academy Awards. Critics deemed it an Oscar pink carpet winner.

In 2002, Mr. Theyskens, then 25, was named inventive director of the revered French couture home Rochas, and he closed his namesake model to concentrate on the project. Although his work there drew nice reward, the corporate’s proprietor, Procter & Gamble, closed the style division in 2006 to concentrate on fragrances, and he was out.

He was picked up by Nina Ricci, the old-line French ready-to-wear label, and swiftly injected it with youthful, sexier vibe. Once more, he was lauded by critics. However he fell out with administration, and in 2009 he was let go. In 2010, Andrew Rosen, the proprietor of Idea, employed him because the New York firm’s creative director. That lasted 4 years.

Mr. Theyskens returned to Paris and in 2016 he restarted his personal enterprise. He staged a number of runway reveals and was promoting to malls and on e-commerce websites. Then the pandemic hit, and style got here to a close to standstill.

He moved his firm to the Marais and ruminated on how he could possibly be extra eco-responsible. His resolutions: stop the relentless seasonal assortment cycle and promoting wholesale to concentrate on made-to-order couture; cease sourcing new materials and work with what he already had — his cache of deadstock and swatches saved at residence, on the workplace and in his mother and father’ attic in Belgium.

To make use of the swatches, he needed to separate them from their cardboard IDs, often eradicating the staples with a fish knife. “It’s fairly time-consuming,” he stated with a quiet chuckle.

He organized the swatches by texture, colour and materials, constructing what he calls a “cloth library.”

As soon as sorted, he began to play with them, like collage. “Here’s a collection of horrible prints,” he stated, opening a drawer stuffed with vibrant florals, zigzags, blotches and extra. “However they may look good as soon as I combine them up with one thing higher.”

He confirmed off a completed piece of fabric in watery hues. “I at all times thought I didn’t like turquoise,” he stated, “however right here it’s, along with lace, and it’s very nice. You by no means know. You conflict patterns and colours, and also you see one thing nice.”

As soon as he has a mix that he likes, he or one among his half-dozen assistants sew the swatches collectively on the bias, to offer the material a forgiving stretch. He stews the fabric in a strain cooker in his kitchen at residence and creases the new, moist mass by hand.

“You maintain it collectively for some time, and once you let it go, you hope it’s OK,” he stated. “Each is an experiment — it’s a must to estimate the way it’s going to shrink and react — and to date, we’ve solely had good surprises, no disasters. I really feel there’s magical good will.”

He prepares his garment prototype — or “toile,” historically product of muslin — by draping equally crushed tissue paper on a model within the form of the shopper, like couture homes have. Utilizing paper reasonably than muslin is “much less wasteful,” he famous.

For the second, Mr. Theyskens is targeted on ladies’s put on, although finally he’d love to do males’s put on. He has some items now that he describes as “nonbinary,” like a trench constructed from black leather-based he purchased from a neighborhood reseller; the pores and skin had been rejected by one other style home due to barely perceptible flaws. He lined the coat with burgundy silk from his deadstock. The result’s good-looking and eco-responsible, which for Mr. Theyskens is the very definition of recent style.

“We have to be targeted on the optimization of every little thing,” he stated as he hung the coat again on the rack. “In my thoughts sustainability can’t be a pattern. It have to be a manner of being. It is smart.”

Lifestyle

Norma Swenson, ‘Our Bodies, Ourselves’ Co-Author, Dies at 93

Norma Swenson was working to educate women about childbirth, championing their right to have a say about how they delivered their babies, when she met the members of the collective that had put out the first rough version of what would become the feminist health classic “Our Bodies, Ourselves.” It was around 1970, and she recalled a few of the women attending a meeting she was holding in Newton, Mass., where she lived.

It did not go well. One of them shouted at her, “You are not a feminist, you’ll never be a feminist and you need to go to school!”

“I was stricken,” Ms. Swenson remembered in a StoryCorps interview in 2018. “But also feeling that maybe she was right. I needed to know more things.”

She did, however, know quite a bit about the medical establishment, the paternalistic and condescending behavior of male doctors — in 1960, only 6 percent of incoming medical students were female — and the harmful effect that behavior had on women’s health. She had lived it, during the birth of her daughter in 1958.

Despite the initial tension — the woman who had berated Ms. Swenson felt her activism was too polite, too old-school — the members of the Boston Women’s Health Book Collective, as they called themselves, invited Ms. Swenson to join their group. She would go on to help make “Our Bodies, Ourselves” a global best seller. It was a relationship that lasted for the next half-century.

Ms. Swenson died on May 11 at her home in Newton. She was 93.

The cause was cancer, her daughter, Sarah Swenson, said.

It was during a women’s liberation conference in Boston in 1969 that a small group began sharing stories of their fraught experiences with doctors. They told of their frustration with the sexism of the medical establishment and of how confounded they were by the lack of knowledge they had about their own bodies. So they set out to learn for themselves, and in so doing they began to assemble a candid and humane encyclopedia of women’s health — by women, for women.

In 1970, the New England Free Press published their first rough version. It was an immediate underground success, with some 225,000 copies eventually sold. The publisher couldn’t keep up with the demand.

Ms. Swenson joined the group in 1971, when commercial publishers were courting the group’s members. After Simon & Schuster published the book in 1973, much gussied up and expanded, it became a juggernaut.

It covered topics that were then considered unmentionable and, in the case of abortion, illegal: sexuality, masturbation, abortion and birth control. There were chapters on body image, rape and self-defense; on heterosexual and lesbian relationships; on childbirth and its aftermath; and, in later editions, on menopause. There were detailed illustrations — including six variations of hymens — and photographs, including a helpful how-to for viewing one’s own vagina with a mirror.

When The New York Times’s chief book critic, Christopher Lehmann-Haupt — a man! — reviewed it, he explained his rationale for giving himself the assignment.

“I learned a great deal from this book that I did not know before, or had somehow forgotten,” he wrote. “And if the authors are correct in their belief that one of the major reasons why men oppress women is because ‘of the male fear and envy of the generative and sexual powers of women’ — and I think they are — why, then, it will do no harm at all for men to read ‘Our Bodies, Ourselves’ and expend a little rational thought on these powers.”

The book revolutionized how women’s health was discussed, and it quickly became a cultural touchstone. Reading it — often under the covers — was a rite of passage for many young women, who nicked it from their mothers’ bedside tables. More progressive moms gave it to their daughters in lieu of “the talk.”

Barbara Ehrenreich called it a manifesto of medical populism. The Moral Majority deemed it obscene. It even had a cameo in “Heartburn,” Nora Ephron’s 1983 revenge novel about the breakup of her marriage.

But the book was always a labor of love. And as the royalties poured in, the Obos, as they called themselves, used the money not to pay themselves but to create a nonprofit that made small grants to women’s health groups.

In 1977, Ms. Swenson and Judy Norsigian, another core member of the collective, teamed up for a tour of 10 European countries to meet with women’s groups who were putting together their own versions of “Our Bodies, Ourselves.” Ms. Swenson would later help to oversee the international editions and adaptations, and would lecture around the world, particularly in developing countries.

“Norma was always committed to an intersectional approach,” Ms. Norsigian said. “She made sure the activism could fit people’s lifestyles. How they could do things with limited resources. How to tailor the work to specific communities in less industrialized countries. She helped breastfeeding support groups in the Philippines, for example, and met with a doctor in Bangladesh who was advocating for indigenous production of essential drugs.”

“Feminism,” Ms. Swenson once told a group of doctors, “is just another name for self-respect.”

Norma Lucille Meras was born on Feb. 2, 1932, in Exeter, N.H., the only child of Halford Meras, who owned the town’s furniture store, and Nellie (Kenick) Meras, who worked as the store’s bookkeeper.

When she was 9, the family moved to Boston. She attended the prestigious Girls’ Latin School (now Boston Latin Academy), graduating in 1949 and studied sociology at Tufts University. She graduated in 1953 and, three years later, married John Swenson, a decorated World War II pilot — he was a member of the 100th Bomb Group of the Eighth Air Force, also known as the Bloody Hundredth — who worked in insurance and for the Post Office.

It was her daughter’s birth that had made Ms. Swenson an activist. She wanted to deliver the baby naturally, without medication. Her decision was such an anomaly that residents at the Boston Lying-In Hospital gathered to watch her labor. It went swimmingly.

But Ms. Swenson, who was in a 12-bed ward, was surrounded by women who were suffering. They were giving birth according to the practices of the era: with a dose of Scopolamine, a drug that induced so-called twilight sleep and hallucinations, followed by a shot of Demerol, an opioid.

She remembered the women screaming, trying to climb out of their beds, calling for their mothers and cursing their husbands before being knocked out by the Demerol, their babies delivered by forceps.

It was barbaric, she thought. “These women weren’t being helped,” she said in 2018, “they were being controlled.”

She became president of the Boston Association for Childbirth Education, which focused on natural childbirth, in 1964, and later served as president of the International Childbirth Education Association. She earned a master’s degree in public health from Harvard in 1973.

Mr. Swenson died in 2002. Ms. Swenson’s partner for the next decade and a half, Leonard van Gaasbeek, died in 2019. Her daughter is her only immediate survivor.

For most of her life, Ms. Swenson traveled the world as an expert on reproductive rights and women’s and children’s health, advising women’s health groups and helping to connect them with policy and grant makers. She taught at the Harvard School of Public Health and served as a consultant to the World Health Organization and other groups.

“Our Bodies, Ourselves,” last updated in 2011, has sold more than four million copies and been translated into 34 languages. The nonprofit behind the book, which provides health resources to women, is now based at Suffolk University in Boston.

“It’s not that things have so dramatically improved for women,” Ms. Swenson told The Times in 1985. “But they’d be much worse if it were not for the pressure of the women’s health movement. We are a presence now that cannot be made to disappear.”

She continued: “Women’s voices are being heard, speaking about their needs and their experiences, and they are not going along with having decisions based simply on what the medical profession needs or what the drug industry needs. I find that enormously exciting.”

Lifestyle

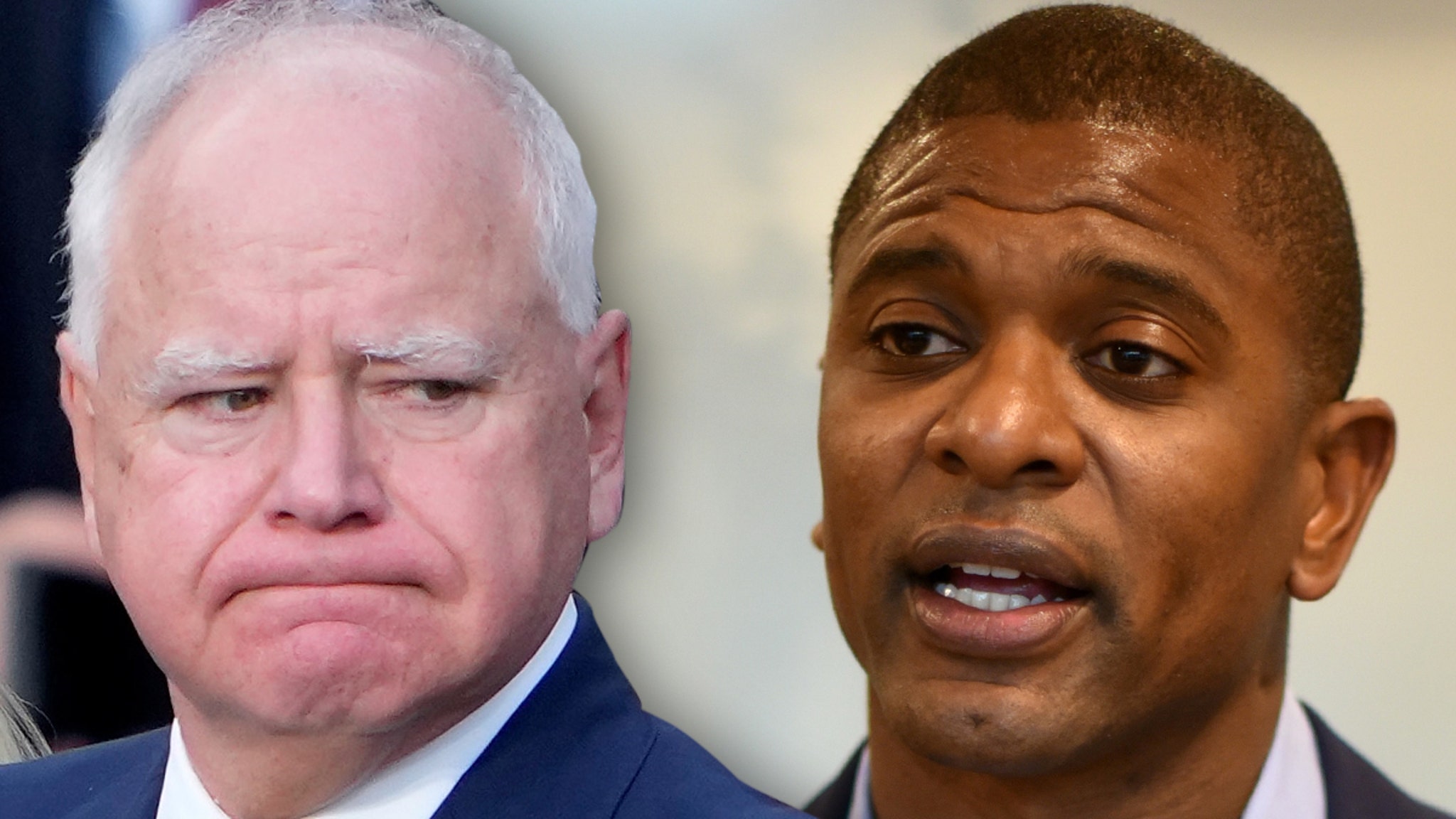

Tim Walz Allowed Minnesota to Become 'Capital of Chaos,' Former Vikings Star Says

Ex-Vikings Star

Minnesota’s The ‘Capital of Chaos’

… I Blame Tim Walz!!!

Published

A former NFL star is blaming Minnesota Governor Tim Walz for allowing chaos to reign in his state … just after two local lawmakers were shot.

Jack Brewer — a four-year player in the league who played two seasons with the Minnesota Vikings — spoke to Fox News Digital about the current state of Minnesota … and, he called it the “Capital of Chaos in America.”

Brewer says it breaks his heart to see the demise of one of the nation’s great states, adding he lived there a long time between going to school at the University of Minnesota and playing for the Vikings … and, he says it wasn’t always this dangerous.

Brewer says Governor Walz and the state’s attorney general, Keith Ellison, have allowed the “liberal hub around Minneapolis and St. Paul” to take over … which is why he thinks the state isn’t what it used to be.

Then, Brewer got a little personal … telling the outlet, “Tim Walz is the example of a weak, emasculated leader. That is not what God made fathers to be. It’s pathetic.”

As you know … law enforcement officers are still searching for Vance Boelter after Assemblywoman Melissa Hortman and State Senator John Hoffman were shot multiple times.

Hortman and her husband, Mark, were both killed while Hoffman and his wife, Yvette, were rushed to the hospital for surgery. They’re in stable condition and recovering.

Vance’s car was discovered 50 miles southwest of Minneapolis — the shooting occurred in two separate suburbs of the city — on Sunday morning. The FBI is offering a $50K reward for information leading to Boelter’s arrest and conviction.

Lifestyle

'Wait Wait' for June 14, 2025: With Not My Job guest Chris Perfetti

Chris Perfetti attends as BBC Studios Los Angeles Productions celebrates 27 Emmy nominations at the BAFTA TV Tea Party at The Maybourne Beverly Hills on September 14, 2024 in Beverly Hills, California. (Photo by Rodin Eckenroth/Getty Images for BBC Studios)

Rodin Eckenroth/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Rodin Eckenroth/Getty Images

This week’s show was recorded in Chicago with guest host Negin Farsad, judge and scorekeeper Bill Kurtis, Not My Job guest Chris Perfetti and panelists Joyelle Nicole Johnson, Alonzo Bodden, and Luke Burbank. Click the audio link above to hear the whole show.

Who’s Bill This Time

Birthday Twins In DC; The Marlboro Man Returns; Getting Your Money’s Worth From Beyonce

Panel Questions

Real ID or Real Bargains?

Bluff The Listener

Our panelists tell three stories of how people’s parents met, only one of which is true.

Not My Job: Abbott Elementary’s Christ Perfetti answers our questions about monks

Chris Perfetti, one of the stars of Abbott Elementary plays our game called, “Abbott Elementary meet the Elementary Abbotts” Three questions about monks.

Panel Questions

Family Time Just Got Easier and Messier; Best Way To Leave A Wedding

Limericks

Bill Kurtis reads three news-related limericks: Still or Sparking or Super Fancy?; A Lovable Loaf; Dating on A Budget

Lightning Fill In The Blank

All the news we couldn’t fit anywhere else

Predictions

Our panelists predict, after the big parades in Washington DC this weekend, what will be the next big parade.

-

West1 week ago

West1 week agoBattle over Space Command HQ location heats up as lawmakers press new Air Force secretary

-

Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoiFixit says the Switch 2 is even harder to repair than the original

-

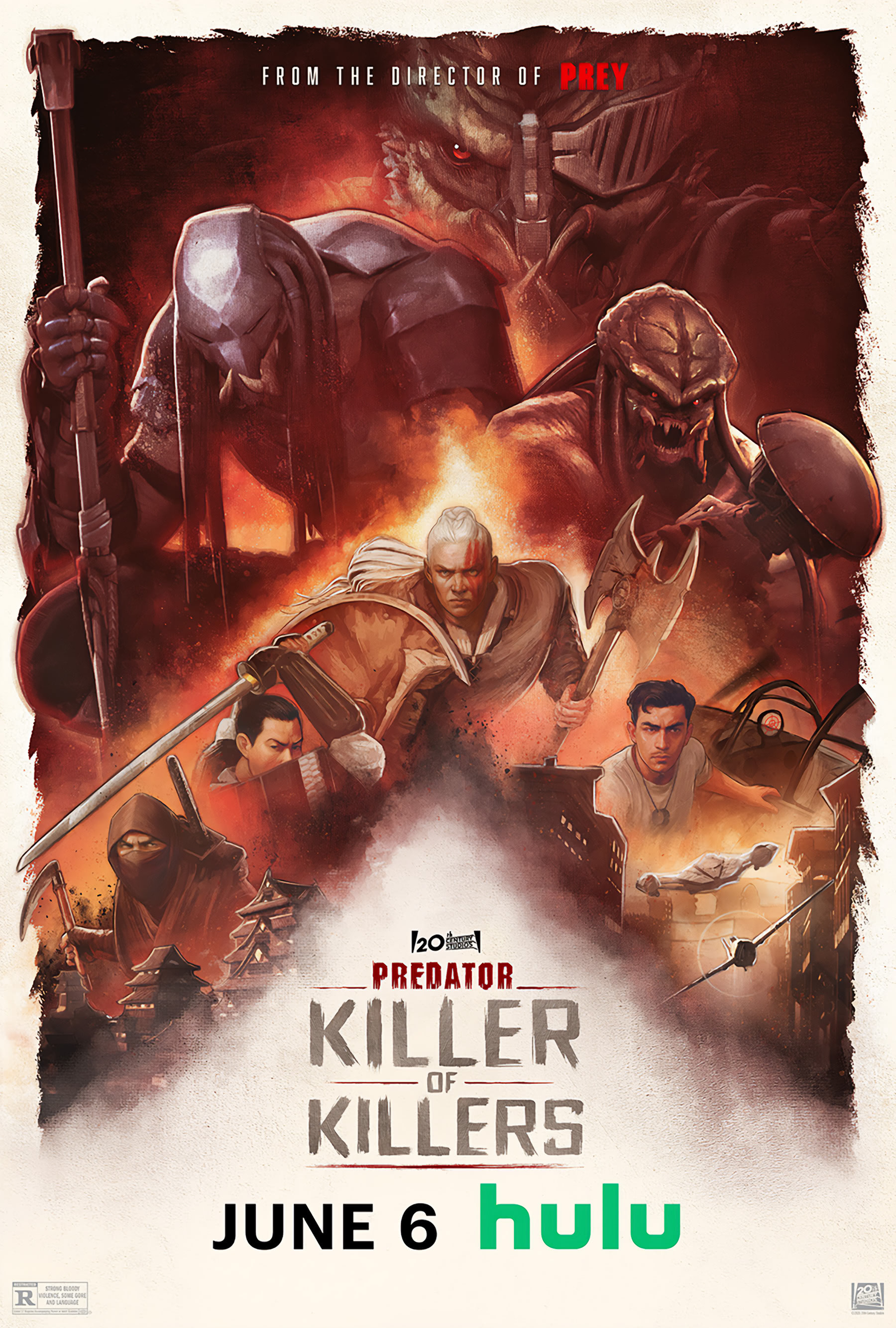

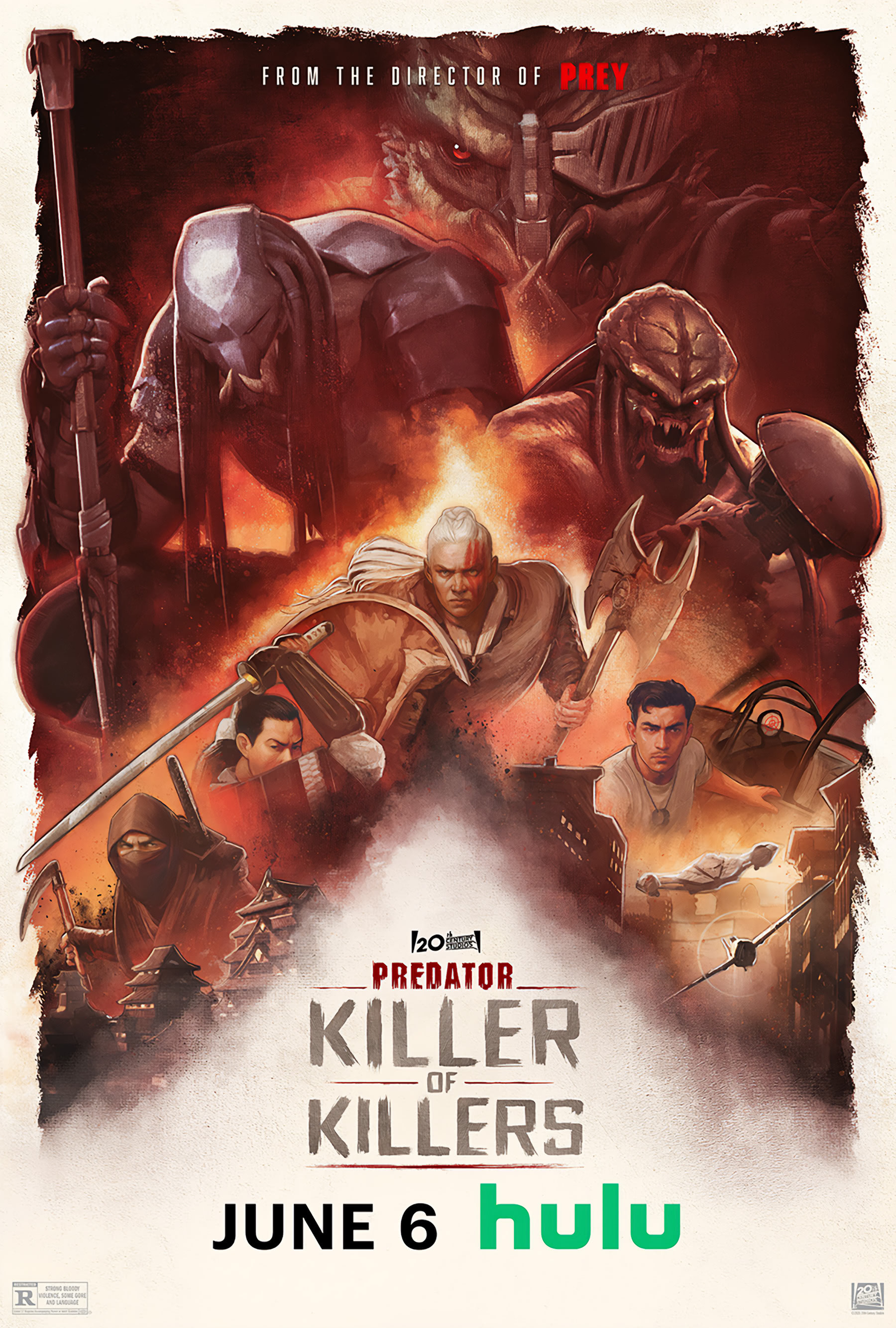

Movie Reviews1 week ago

Movie Reviews1 week agoPredator: Killer of Killers (2025) Movie Review | FlickDirect

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoA History of Trump and Elon Musk's Relationship in their Own Words

-

Finance1 week ago

Finance1 week agoChinese lenders among top backers of “forest-risk” firms

-

Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoThere are only two commissioners left at the FCC

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoA former police chief who escaped from an Arkansas prison is captured

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoUkraine: Kharkiv hit by massive Russian aerial attack