Lifestyle

Marcel Ophuls, who chronicled 20th century conflict and atrocities, dies at 97

Marcel Ophuls believed subjectivity was key to filmmaking and saw documentaries as an antidote to the news. He’s pictured above on May 5, 1987.

Chip Hires/Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Chip Hires/Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images

Marcel Ophuls believed subjectivity was key to filmmaking and saw documentaries as an antidote to the news. He’s pictured above on May 5, 1987.

Chip Hires/Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images

Filmmaker Marcel Ophuls has died at the age of 97. Recognized as one of the great documentarians of his era, he died on Saturday, as confirmed by his grandson, Andréas-Benjamin Seyfert.

Ophuls demanded — and commanded — his audience’s attention, in 4 plus hour documentaries like The Sorrow and The Pity and Hôtel Terminus.

Ophuls knew that by creating hours-long documentaries, he ran the danger of “not only seeming pretentious, but being pretentious.” But, as he told NPR in 1978, “there’s a relationship between attention span and morality. I think that, if you shorten people’s attention span a great deal, you are left with only the attraction of power.”

Ophuls was born in Germany and his family fled to France to escape the Nazis. They eventually ended up in Hollywood, where his father, the famed director Max Ophuls, found work. His son started out making fiction films, too, but went on to become one of the foremost chroniclers of the atrocities of the 20th century.

The Sorrow and The Pity is Ophuls’ 1969 epic about the Nazi occupation of France. He interviewed former Nazis, French officials who collaborated, members of the Resistance, and average people who simply found ways to get by. Throughout the film, Ophuls appears on camera—patiently drawing confessions from his subjects. The film faced criticism in France for its depiction of the country’s war efforts.

The Sorrow and The Pity became an art house hit, says Patricia Aufderheide, who teaches communications at American University in Washington, D.C. — and it helped create a new kind of documentary.

“It’s a kind of filmmaking where the filmmaker is very present as an investigator into something about the human condition,” she says.

Ophuls told NPR in 1992 that documentaries function as an antidote to news. Subjectivity is key, he said; the goal is “to juxtapose events and people in such a way that individual destinies and collective destinies make us think and reflect about our own roles in life.”

Ophuls was good at putting old Nazis and retired U.S. intelligence workers at their ease, as he does in his 1988 film Hôtel Terminus, about Klaus Barbie — a notorious Nazi — and the Americans who later protected him. When the film crew arrived to set up for interviews, Ophuls stayed in the back of the room, letting the crew chat up the subject.

Judy Karp, the filmmaker’s U.S. sound recordist, says Ophuls would adapt to make the interviewee comfortable. “He would come in as the person that he needed to be in order to get the story out of them and to get the information that he wanted,” Karp says. “He was never false — but it’s like we never knew which Marcel was going to be there.”

For Hôtel Terminus, which won the best documentary feature Oscar in 1988, Ophuls interviewed French writer and philosopher René Tavernier, who lived through the period the film covers. His son, acclaimed director Bertrand Tavernier, described Ophuls as one of the greatest of all filmmakers, not just documentarians.

“He knew that documentary sometimes has to be built as a fiction film,” Tavernier told NPR in an interview before his own passing in 2021. “You have to have interesting characters. You have to have an interesting angle. You have to work on dramatization, progression. At the same time, he was never manipulating the audience.”

His stories were true, but Ophuls thought of himself as an entertainer nonetheless. In 1978, he told NPR that his greatest hero in show business — and yes, he considered himself in show business — was Fred Astaire. The dancer’s “control and structure and balance is so dignified, and so rarified,” he said.

In 1992, he told NPR that his mission was to make the world a better place through his work, going beyond entertainment. “That’s what we live for, isn’t it?” he said. “To try to make it better.”

Lifestyle

In Brooklyn’s Park Slope neighborhood, children’s entertainment comes with strings

The Tin Soldier, one of Nicolas Coppola’s marionette puppets, is the main character in The Steadfast Tin Soldier show at Coppola’s Puppetworks theater in Brooklyn’s Park Slope neighborhood.

Anh Nguyen for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Anh Nguyen for NPR

Every weekend, at 12:30 or 2:30 p.m., children gather on foam mats and colored blocks to watch wooden renditions of The Tortoise and the Hare, Pinocchio and Aladdin for exactly 45 minutes — the length of one side of a cassette tape. “This isn’t a screen! It’s for reals happenin’ back there!” Alyssa Parkhurst, a 24-year-old puppeteer, says before each show. For most of the theater’s patrons, this is their first experience with live entertainment.

Puppetworks has served Brooklyn’s Park Slope neighborhood for over 30 years. Many of its current regulars are the grandchildren of early patrons of the theater. Its founder and artistic director, 90-year-old Nicolas Coppola, has been a professional puppeteer since 1954.

The Puppetworks theater in Brooklyn’s Park Slope neighborhood.

Anh Nguyen for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Anh Nguyen for NPR

A workshop station behind the stage at Puppetworks, where puppets are stored and repaired.

Anh Nguyen for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Anh Nguyen for NPR

A picture of Nicolas Coppola, Puppetworks’ founder and artistic director, from 1970, in which he’s demonstrating an ice skater marionette puppet.

Anh Nguyen for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Anh Nguyen for NPR

For just $11 a seat ($12 for adults), puppets of all types — marionette, swing, hand and rod — take turns transporting patrons back to the ’80s, when most of Puppetworks’ puppets were made and the audio tracks were taped. Century-old stories are brought back to life. Some even with a modern twist.

Since Coppola started the theater, changes have been made to the theater’s repertoire of shows to better meet the cultural moment. The biggest change was the characterization of princesses in the ’60s and ’70s, Coppola says: “Now, we’re a little more enlightened.”

Right: Michael Jones, Puppetworks’ newest puppeteer, poses for a photo with Jack-a-Napes, one of the main characters in The Steadfast Tin Soldier. Left: A demonstration marionette puppet, used for showing children how movement and control works.

Anh Nguyen for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Anh Nguyen for NPR

Marionette puppets from previous Puppetworks shows hang on one of the theater’s walls.

Anh Nguyen for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Anh Nguyen for NPR

A child attends Puppetworks’ 12:30 p.m. showing on Saturday, Dec. 6, dressed in holiday attire that features the ballerina and tin soldier in The Steadfast Tin Soldier.

Anh Nguyen for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Anh Nguyen for NPR

Streaming has also influenced the theater’s selection of shows. Puppetworks recently brought back Rumpelstiltskin after the tale was repopularized following Dreamworks’ release of the Shrek film franchise.

Most of the parents in attendance find out about the theater through word of mouth or school visits, where Puppetworks’ team puts on shows throughout the week. Many say they take an interest in the establishment for its ability to peel their children away from screens.

Whitney Sprayberry was introduced to Puppetworks by her husband, who grew up in the neighborhood. “My husband and I are both artists, so we much prefer live entertainment. We allow screens, but are mindful of what we’re watching and how often.”

Left: Puppetworks’ current manager of stage operations, Jamie Moore, who joined the team in the early 2000s as a puppeteer, holds an otter hand puppet from their holiday show. Right: A Pinocchio mask hangs behind the ticket booth at Puppetworks’ entrance.

Anh Nguyen for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Anh Nguyen for NPR

A child attends Puppetworks’ 12:30 p.m. showing on Saturday, Dec. 6, dressed in holiday attire.

Anh Nguyen for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Anh Nguyen for NPR

Left: Two gingerbread people, characters in one of Puppetworks’ holiday skits. Right: Ronny Wasserstrom, a swing puppeteer and one of Puppetworks’ first puppeteers, holds a “talking head” puppet he made, wearing matching shirts.

Anh Nguyen for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Anh Nguyen for NPR

Other parents in the audience say they found the theater through one of Ronny Wasserstrom’s shows. Wasserstrom, one of Puppetworks’ first puppeteers, regularly performs for free at a nearby park.

Coppola says he isn’t a Luddite — he’s fascinated by animation’s endless possibilities, but cautions of how it could limit a child’s imagination. “The part of theater they’re not getting by being on the phone is the sense of community. In our small way, we’re keeping that going.”

Puppetworks’ 12:30 p.m. showing of The Steadfast Tin Soldier and The Nutcracker Sweets on Saturday, Dec. 6.

Anh Nguyen for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Anh Nguyen for NPR

Children get a chance to see one of the puppets in The Steadfast Tin Soldier up close after a show.

Anh Nguyen for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Anh Nguyen for NPR

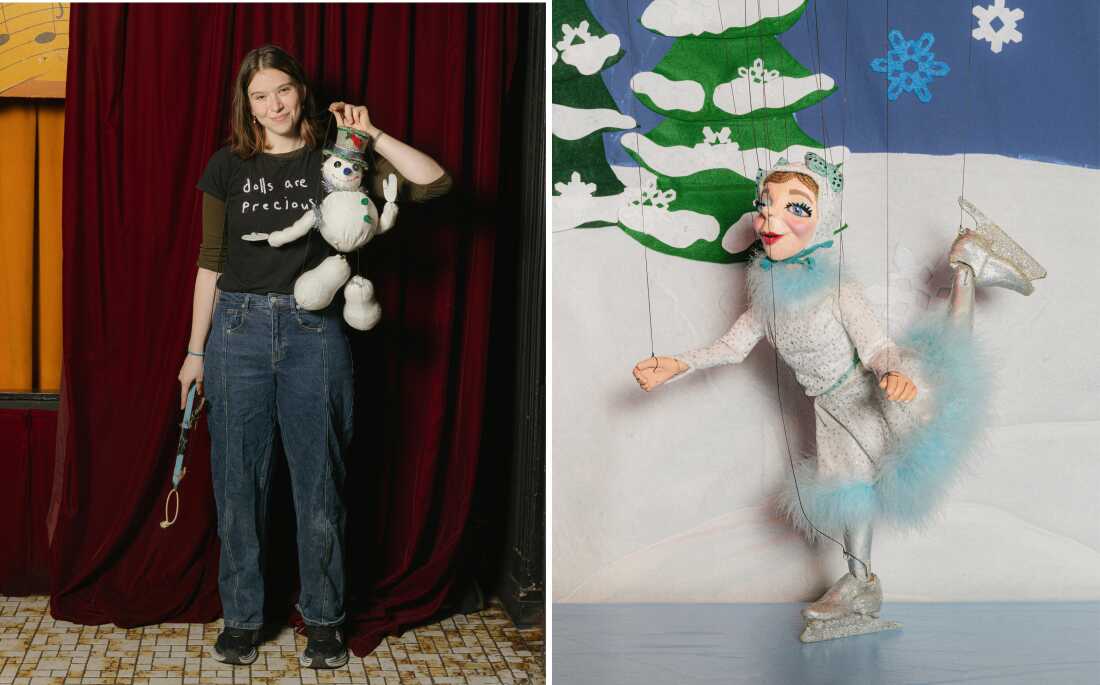

Left: Alyssa Parkhurst, Puppetworks’ youngest puppeteer, holds a snowman marionette puppet, a character in the theater’s holiday show. Right: An ice skater, a dancing character in one of Puppetworks’ holiday skits.

Anh Nguyen for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Anh Nguyen for NPR

Community is what keeps Sabrina Chap, the mother of 4-year-old Vida, a regular at Puppetworks. Every couple of weeks, when Puppetworks puts on a new show, she rallies a large group to attend. “It’s a way I connect all the parents in the neighborhood whose kids go to different schools,” she said. “A lot of these kids live within a block of each other.”

Three candy canes — dancing characters in one of Puppetworks’ holiday skits — wait to be repaired after a show.

Anh Nguyen for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Anh Nguyen for NPR

Anh Nguyen is a photographer based in Brooklyn, N.Y. You can see more of her work online, at nguyenminhanh.com , or on Instagram, at @minhanhnguyenn. Tiffany Ng is a tech and culture writer. Find more of her work on her website, breakfastatmyhouse.com.

Lifestyle

The Best of BoF 2025: Fashion’s Year of Designer Revamps

Lifestyle

Best Christmas gift I ever received : Pop Culture Happy Hour

-

Iowa1 week ago

Iowa1 week agoAddy Brown motivated to step up in Audi Crooks’ absence vs. UNI

-

Maine1 week ago

Maine1 week agoElementary-aged student killed in school bus crash in southern Maine

-

Maryland1 week ago

Maryland1 week agoFrigid temperatures to start the week in Maryland

-

New Mexico7 days ago

New Mexico7 days agoFamily clarifies why they believe missing New Mexico man is dead

-

South Dakota1 week ago

South Dakota1 week agoNature: Snow in South Dakota

-

Detroit, MI1 week ago

Detroit, MI1 week ago‘Love being a pedo’: Metro Detroit doctor, attorney, therapist accused in web of child porn chats

-

Health1 week ago

Health1 week ago‘Aggressive’ new flu variant sweeps globe as doctors warn of severe symptoms

-

Maine7 days ago

Maine7 days agoFamily in Maine host food pantry for deer | Hand Off