Lifestyle

Inside L.A.'s oldest letterpress printer beloved by celebs, from Oprah to Jon Hamm

Surviving in an obsolete industry as long as Aardvark Letterpress has requires fundamental elements of entrepreneurship. Skill, dedication, creativity and professionalism are essential. General manager and co-owner Cary Ocon returns to another theme that’s kept what’s now the city’s oldest letterpress print shop running since 1968.

“Dumb luck,” he says.

Brothers Brooks and Cary Ocon on the floor of Aardvark Letterpress.

A test negative taped to the window of Aardvark’s office.

The lack of pretense and polish here belies the pedigree of much of Aardvark’s client base. Entertainment, fashion, art and other creative industries converge at the unlikely corner of 7th and Carondelet streets overlooking the southwest edge of MacArthur Park. Both basic and technically complex, making letterpress goods is a process that involves the physical act of pressing inked plates onto paper using mechanical presses in a manner that literally leaves a deeper impression.

A look through samples of artful work imprinted with boldfaced names and known entities from Apple to Rihanna’s Fenty Corp. to Valentino to Billie Eilish reveals the many layers of exceptionalism at work that inspire trusting partnerships. When actor and producer Jamie Lee Curtis established her production company Comet Pictures in 2019, “Aardvark Letterpress helped me start off with a strong logo and design,” she shares via text message. “I’m grateful for their expertise and guidance.”

In addition to relying on Aardvark to help shape their professional image and branding, people come here for a richly tactile experience. Personally printed matter made with this level of care has a way of inspiring connection and celebration.

“Cary and the team at Aardvark represent that sadly disappearing sector of tradecraft in the current culture,” actor Jon Hamm says via email. “Singularly, almost maniacally, devoted to one thing, they practice an attention to detail that is as precise and exacting as it is gorgeous in its finished quality.”

“We were typographers before we were printers,” Cary says, pointing to the hulking Intertype brand typography machine dating from the early 20th century that stands in one of the shop windows. With its complex movements that cast lead into a mold to form letters, leaving piles of shavings that get repurposed, it’s the original piece of equipment Cary’s father, Luis Ocon, obtained when he bought Aardvark Typographers 56 years ago in its previous location on Grand View Avenue.

The atmosphere is earnest and soulful, imbued with the makings of a one-act play setting and populated with a cast of characters. Gently sarcastic Cary handles overall management duties, while technically minded Brooks Ocon is the hands-on printing expert, alongside laser-focused master printer Bill Berkuta. Derek Pettet, a friend of Cary’s since the fourth grade, adds to the familiar dynamic.

Brooks Ocon aligns a block for printing.

Master Printer Bill Berkuta prints an order for a customer.

Another moment of good timing came in 1988 when Brooks went to run an errand at H.G. Daniels art supply store on 6th Street. He couldn’t find what he was looking for, so he was directed to McManus & Morgan Fine Art Paper nearby. Brooks noticed a “for lease” sign in an adjacent storefront inside the detailed 1924 Spanish Colonial Revival-style Westlake Square Building designed by architect Everett H. Merrill. It struck him as an ideal place for Aardvark to put down new roots, and his father agreed.

“This was the original art district,” Cary notes, referencing the erstwhile concentration of art schools in the area. Otis Art Institute (later renamed Otis College of Art and Design), the ArtCenter School (ArtCenter College of Design) and Chouinard Art Institute, which was the predecessor of CalArts, were clustered within blocks of each other before relocating to their respective campuses. Multiple art supply stores catered to the student population.

The initial period of Aardvark Letterpress becoming a studio whose services are prized among glitterati clientele like Oprah Winfrey and art galleries and fashion houses, however, was not so smooth.

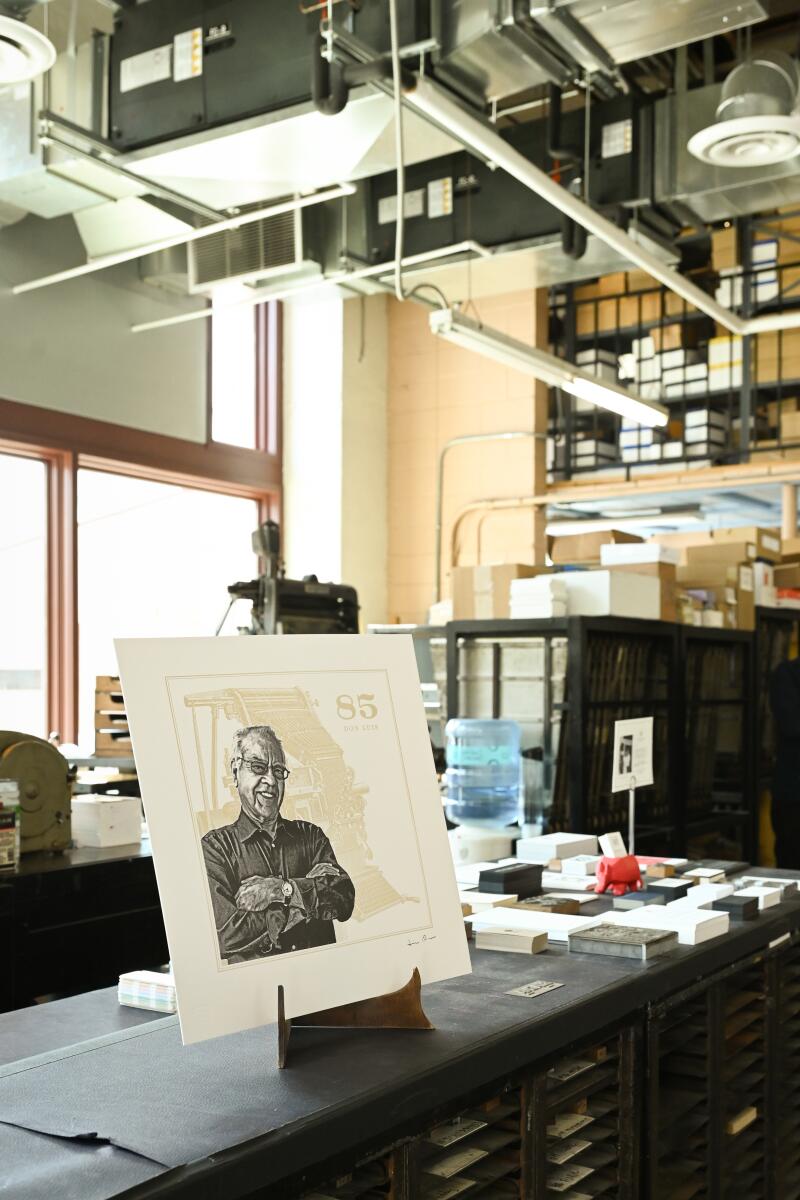

A print of founder Luis Ocon at Aardvark’s entrance.

A view of Aardvark from South Carondelet Street.

A self-taught newspaper Linotype operator who immigrated to the U.S. from Mexico City, Luis Ocon’s purchase of Aardvark Typographers from his former boss Ken Matson coincided with the early adoption of computerized typesetting. “The business just started to nosedive because no one’s doing metal type anymore,” Cary explains. A customer suggested they learn to print in order to adapt to the changing times. “We got our first press and stumbled our way through letterpress printing,” Cary recalls.

While Cary was earning degrees at UC Berkeley and the University of Minnesota and then embarked on what would be an unsatisfying law career, Brooks and Luis were “struggling” to keep Aardvark afloat. Patriarch Luis, who passed away last year at the age of 86, was their stepfather who raised them as his own after meeting their mother, Helen, when Luis and Helen worked at the Holland House Cafeteria in what was Britts Department Store across the street from the Original Farmers Market. (The Ocon brothers also have two sisters and a half-sister.)

Decades before exclusive event planners trusted Aardvark Letterpress to create exquisite wedding invitations and noted artists such as Shepard Fairey partnered with the team on limited edition letterpress works, the business was hyper-local. Mariachi musicians would walk in on a Monday morning needing a fresh supply of business cards after a busy weekend promoting their talents.

Otis Art Institute in its original Westlake location accounted for the occasional job, and Gary Wolin, who still owns the century-old McManus & Morgan, referred customers who needed to print on the specialized papers he sold. The simpatico, closely connected businesses remain neighbors after Wolin downsized within the same building. (Newer tenants in the recently renovated property include taste-making firm Commune Design and Hannah Hoffman gallery.)

“We were a secret among graphic designers,” says Cary, who joined the business full time in 1998. Otis alumni would remember the old school print shop down the street, where the 1920s stencil-painted ceilings, multiple Heidelberg, Germany-made production presses, sturdy wooden drawers full of brass type in hundreds of fonts and other tools still serve as a portal to a pre-digital era.

One of Aardvark’s six Heidelberg presses, vintage printing machines that apply designs directly to paper.

Because cultural tastes and trends have a way of being cyclical, toughing it out eventually paid off. Cary points to Martha Stewart’s championing of letterpress stationery as part of the reason why a revival came around in the early aughts. Aardvark was ready to meet new demand. “Again, it was dumb luck, because we had all the ability to set type.”

In this analog environment computers are used to manage workflow, and a processor upstairs transfers digital design files to make polymer plates used for most jobs. (Aardvark turns to A&G Engraving in Vernon to fabricate photoengraver metal plates for select projects and fine art prints.) This team’s expertise remains unrivaled in L.A. To mix inks, for instance, Berkuta refers to the color recipes on his well-worn Pantone fan deck and then relies on his eye and experience. “I’m weighing it in my head,” he says about getting the ratios right.

“I have collaborated with the team at the Aardvark studio adjusting plate pressure, ink colors and translucency to achieve sublime effects that no other medium can deliver,” artist Fairey states via email.

A linotype detail.

A Marilyn Monroe print on foil.

“I consider the invitations, menus and other objects they provided for our wedding to be works of art. Turns out 100 years of experience is worth something!” Hamm adds.

Despite the accolades, Cary is upfront about the challenges of sustaining this artisan enterprise. “To even print a simple business card, it’s much more labor intensive, so we can’t do it for 50 bucks,” he explains. To keep evolving, he’s preparing to launch Aardvark Printworks, a collection of letterpress art featuring imagery such as artists’ renderings of L.A. landmarks.

“I didn’t appreciate what we were doing,” Cary reflects about his earlier relationship to Aardvark Letterpress’ niche trade. “I see how it does move people.” Even if the family has yet to devise a clear succession plan for the future, the Ocons are proud of their legacy. “It’s something special. We’re thankful we can keep going,” Cary says.

Their impact reaches beyond Los Angeles. “I value a family business that keeps the craft of letterpress, an important printmaking tradition, alive and accessible to L.A. artists and businesses,” Fairey echoes.

Lifestyle

‘The Fall and Rise of Reggie Dinkins’ falls before it rises — but then it soars

Tracy Morgan, left, and Daniel Radcliffe star in The Fall and Rise of Reggie Dinkins.

Scott Gries/NBC

hide caption

toggle caption

Scott Gries/NBC

Tracy Morgan, as a presence, as a persona, bends the rules of comedy spacetime around him.

Consider: He’s constitutionally incapable of tossing off a joke or an aside, because he never simply delivers a line when he can declaim it instead. He can’t help but occupy the center of any given scene he’s in — his abiding, essential weirdness inevitably pulls focus. Perhaps most mystifying to comedy nerds is the way he can take a breath in the middle of a punchline and still, somehow, land it.

That? Should be impossible. Comedy depends on, is entirely a function of, timing; jokes are delicate constructs of rhythms that take time and practice to beat into shape for maximum efficiency. But never mind that. Give this guy a non-sequitur, the nonner the better, and he’ll shout that sucker at the top of his fool lungs, and absolutely kill, every time.

Well. Not every time, and not everywhere. Because Tracy Morgan is a puzzle piece so oddly shaped he won’t fit into just any world. In fact, the only way he works is if you take the time and effort to assiduously build the entire puzzle around him.

Thankfully, the makers of his new series, The Fall and Rise of Reggie Dinkins, understand that very specific assignment. They’ve built the show around Morgan’s signature profile and paired him with an hugely unlikely comedy partner (Daniel Radcliffe).

The co-creators/co-showrunners are Robert Carlock, who was one of the showrunners on 30 Rock and co-created The Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt, and Sam Means, who also worked on Girls5eva with Carlock and has written for 30 Rock and Kimmy Schmidt.

These guys know exactly what Morgan can do, even if 30 Rock relegated him to function as a kind of comedy bomb-thrower. He’d enter a scene, lob a few loud, puzzling, hilarious references that would blow up the situation onscreen, and promptly peace out through the smoke and ash left in his wake.

That can’t happen on Reggie Dinkins, as Tracy is the center of both the show, and the show-within-the-show. He plays a former NFL star disgraced by a gambling scandal who’s determined to redeem himself in the public eye. He brings in an Oscar-winning documentarian Arthur Tobin (Radcliffe) to make a movie about him and his current life.

Tobin, however, is determined to create an authentic portrait of a fallen hero, and keeps goading Dinkins to express remorse — or anything at all besides canned, feel-good platitudes. He embeds himself in Dinkins’ palatial New Jersey mansion, alongside Dinkins’ fiancée Brina (Precious Way), teenage son Carmelo (Jalyn Hall) and his former teammate Rusty (Bobby Moynihan), who lives in the basement.

If you’re thinking this means Reggie Dinkins is a show satirizing the recent rise of toothless, self-flattering documentaries about athletes and performers produced in collaboration with their subjects, you’re half-right. The show feints at that tension with some clever bits over the course of the season, but it’s never allowed to develop into a central, overarching conflict, because the show’s more interested in the affinity between Dinkins and Tobin.

Tobin, it turns out, is dealing with his own public disgrace — his emotional breakdown on the set of a blockbuster movie he was directing has gone viral — and the show becomes about exploring what these two damaged men can learn from each other.

On paper, sure: It’s an oil-and-water mixture: Dinkins (loud, rich, American, Black) and Tobin (uptight, pretentious, British, practically translucent). Morgan’s in his element, and if you’re not already aware of what a funny performer Radcliffe can be, check him out on the late lamented Miracle Workers.

Whenever these two characters are firing fusillades of jokes at each other, the series sings. But, especially in the early going, the showrunners seem determined to put Morgan and Radcliffe together in quieter, more heartfelt scenes that don’t quite work. It’s too reductive to presume this is because Morgan is a comedian and Radcliffe is an actor, but it’s hard to deny that they’re coming at those moments from radically different places, and seem to be directing their energies past each other in ways that never quite manage to connect.

Precious Way as Brina.

Scott Gries/NBC

hide caption

toggle caption

Scott Gries/NBC

It’s one reason the show flounders out of the gate, as typical pilot problems pile up — every secondary character gets introduced in a hurry and assigned a defining characteristic: Brina (the influencer), Rusty (the loser), Carmelo (the TV teen). It takes a bit too long for even the great Erika Alexander, who plays Dinkins’ ex-wife and current manager Monica, to get something to play besides the uber-competent, work-addicted businesswoman.

But then, there are the jokes. My god, these jokes.

Reggie Dinkins, like 30 Rock and Kimmy Schmidt before it, is a joke machine, firing off bit after bit after bit. But where those shows were only too happy to exist as high-key joke-engines first, and character comedies second, Dinkins is operating in a slightly lower register. It’s deliberately pitched to feel a bit more grounded, a bit less frenetic. (To be fair: Every show in the history of the medium can be categorized as more grounded and less frenetic than 30 Rock and Kimmy Schmidt — but Reggie Dinkins expressly shares those series’ comedic approach, if not their specific joke density.)

While the hit rate of Reggie Dinkins‘ jokes never achieves 30 Rock status, rest assured that in episodes coming later in the season it comfortably hovers at Kimmy Schmidt level. Which is to say: Two or three times an episode, you will encounter a joke that is so perfect, so pure, so diamond-hard that you will wonder how it has taken human civilization until 2026 Common Era to discover it.

And that’s the key — they feel discovered. The jokes I’m talking about don’t seem painstakingly wrought, though of course they were. No, they feel like they have always been there, beneath the earth, biding their time, just waiting to be found. (Here, you no doubt will be expecting me to provide some examples. Well, I’m not gonna. It’s not a critic’s job to spoil jokes this good by busting them out in some lousy review. Just watch the damn show to experience them as you’re meant to; you’ll know which ones I’m talking about.)

Now, let’s you and I talk about Bobby Moynihan.

As Rusty, Dinkins’ devoted ex-teammate who lives in the basement, Moynihan could have easily contented himself to play Pathetic Guy™ and leave it at that. Instead, he invests Rusty with such depths of earnest, deeply felt, improbably sunny emotions that he solidifies his position as show MVP with every word, every gesture, every expression. The guy can shuffle into the far background of a shot eating cereal and get a laugh, which is to say: He can be literally out-of-focus and still steal focus.

Which is why it doesn’t matter, in the end, that the locus of Reggie Dinkins‘ comedic energy isn’t found precisely where the show’s premise (Tracy Morgan! Daniel Radcliffe! Imagine the chemistry!) would have you believe it to be. This is a very, very funny — frequently hilarious — series that prizes well-written, well-timed, well-delivered jokes, and that knows how to use its actors to serve them up in the best way possible. And once it shakes off a few early stumbles and gets out of its own way, it does that better than any show on television.

This piece also appeared in NPR’s Pop Culture Happy Hour newsletter. Sign up for the newsletter so you don’t miss the next one, plus get weekly recommendations about what’s making us happy.

Listen to Pop Culture Happy Hour on Apple Podcasts and Spotify.

Lifestyle

How to have the best Sunday in L.A., according to Andy Richter

Andy Richter has found his place.

The Chicago area native previously lived in New York — where he first found fame as Conan O’Brien’s sidekick on “Late Night” — before moving to Los Angeles in 2001. Three years ago, he moved to Pasadena. “Now that I live here, I would not live anywhere else,” he says.

There are some practical benefits to the city. “I am such a crabby old man now, but it’s like, there’s parking, you can park when we have to go out,” Richter says. “The notion of going to dinner in Santa Monica just feels like having nails shoved into my feet.”

In Sunday Funday, L.A. people give us a play-by-play of their ideal Sunday around town. Find ideas and inspiration on where to go, what to eat and how to enjoy life on the weekends.

But he mostly appreciates that Pasadena is “a very diverse town and just a beautiful town,” he says.

For Richter, most Sundays revolve around his family. In 2023, the comedian and actor married creative executive Jennifer Herrera and adopted her young daughter, Cornelia. (He also has two children in their 20s, William and Mercy, from his previous marriage.)

Additionally, he’s been giving his body time to recover. Richter spent last fall training and competing on the 34th season of “Dancing With the Stars.” And though he had no prior dancing experience, he won over the show’s fan base with his kindness and dedication, making it to the competition’s ninth week.

He hosts the weekly show “The Three Questions” on O’Brien’s Team Coco podcast network and still appears in films and TV shows. “I’m just taking meetings and auditioning like every other late 50s white comedy guy in L.A., sitting around waiting for the phone to ring.”

This interview has been lightly edited and condensed for length and clarity.

7:30 a.m.: Early rising

It’s hard for me at this advanced age to sleep much past 7:30. I have a 5 1/2-year-old, and hopefully she’ll sleep in a little bit longer so my wife and I can talk and snuggle and look at our phones at opposite ends of the bed, like everybody.

Then the dogs need to be walked. I have two dogs: a 120-pound Great Pyrenees-Border Collie-German Shepherd mix, and then at the other end of the spectrum, a seven-pound poodle mix. We were a blended dog family. When my wife and I met, I had the big dog and she had a little dog. Her first dog actually has passed, but we like that dynamic. You get kind of the best of both worlds.

8 a.m.: Breakfast at a classic diner

Then it would probably be breakfast at Shakers, which is in South Pasadena. It’s one of our favorite places. We’re kind of regulars there, and my daughter loves it. It’s easy with a 5-year-old, you’ve got to do what they want. They’re terrorists that way, especially when it comes to cuisine.

I’ve lived in Pasadena for about three years now, but I have been going to Shakers for a long time because I have a database of all the best diners in the Los Angeles metropolitan area committed to memory. There’s just something about the continuity of them that makes me feel like the world isn’t on fire. And because of L.A.’s moderate climate, the ones here stay the way they are; whereas if you get 18 feet of winter snow, you tend to wear down the diner floor, seats, everything.

So there’s a lot of really great old places that stay the same. And then there are tragic losses. There’s been some noise that Shakers is going to turn into some kind of condo development. I think that people would probably riot. They would be elderly people rioting, but they would still riot.

11 a.m.: Sandy paws

My in-laws live down in Long Beach, so after breakfast we might take the dogs down to Long Beach. There’s this dog beach there, Rosie’s Beach. I have never seen a fight there between dogs. They’re all just so happy to be out and off-leash, with an ocean and sand right there. You get a contact high from the canine joy.

1 p.m.: Lunch in Belmont Shore

That would take us to lunchtime and we’ll go somewhere down there. There’s this place, L’Antica Pizzeria Da Michele, in Belmont Shore. It’s fantastic for some pizza with grandma and grandpa. It’s originally from Naples. There’s also one in Hollywood where Cafe Des Artistes used to be on that weird little side street.

4 p.m.: Sunset at the gardens

We’d take grandma and grandpa home, drop the dogs off. We’d go to the Huntington and stay a couple of hours until sunset. The Japanese garden is pretty mind-blowing. You feel like you’re on the set of “Shogun.”

The main thing that I love about it is the changing of ecospheres as you walk through it. Living in the area, I drive by it a thousand times and then I remember, “Oh yeah, there’s a rainforest in here. There’s thick stands of bamboo forest that look like Vietnam.” It’s beautiful. With all three of my kids, I have spent a lot of time there.

6:30 p.m.: Mall of America

After sundown, we will go to what seems to be the only thriving mall in America — [the Shops at] Santa Anita. We are suckers for Din Tai Fung. My 24-year-old son, who’s kind of a food snob, is like, “There’s a hundred places that are better and cheaper within five minutes of there in the San Gabriel Valley.” And we’re like, “Yeah, but this is at the mall.” It’s really easy. Also, my wife is a vegetarian, and a lot of the more authentic places, there’s pork in the air. It’s really hard to find vegetarian stuff.

We have a whole system with Din Tai Fung now, which is logging in on the wait list while we’re still on the highway, or ordering takeout. There’s plenty of places in the mall with tables, you can just sit down and have your own little feast there.

There’s also a Dave & Buster’s. If you want sensory overload, you can go in there and get a big, big booze drink while you’re playing Skee-Ball with your kid.

9 p.m.: Head to bed ASAP

I am very lucky in that I’m a very good sleeper and the few times in my life when I do experience insomnia, it’s infuriating to me because I am spoiled, basically. When you’ve got a 5 1/2-year-old, there’s no real wind down. It’s just negotiations to get her into bed and to sleep as quickly as possible, so we can all pass out.

Lifestyle

Video: Prada Peels Back the Layers at Milan Fashion Week

new video loaded: Prada Peels Back the Layers at Milan Fashion Week

By Chevaz Clarke and Daniel Fetherston

February 27, 2026

-

World3 days ago

World3 days agoExclusive: DeepSeek withholds latest AI model from US chipmakers including Nvidia, sources say

-

Massachusetts3 days ago

Massachusetts3 days agoMother and daughter injured in Taunton house explosion

-

Montana1 week ago

Montana1 week ago2026 MHSA Montana Wrestling State Championship Brackets And Results – FloWrestling

-

Louisiana6 days ago

Louisiana6 days agoWildfire near Gum Swamp Road in Livingston Parish now under control; more than 200 acres burned

-

Denver, CO3 days ago

Denver, CO3 days ago10 acres charred, 5 injured in Thornton grass fire, evacuation orders lifted

-

Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoYouTube TV billing scam emails are hitting inboxes

-

Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoStellantis is in a crisis of its own making

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoOpenAI didn’t contact police despite employees flagging mass shooter’s concerning chatbot interactions: REPORT