Lifestyle

In a collection of 40+ interviews, author Adam Moss tries to find the key to creation

Adam Moss allowed NPR into a space only two other people have seen: his painting studio.

Adam Moss

hide caption

toggle caption

Adam Moss

Adam Moss allowed NPR into a space only two other people have seen: his painting studio.

Adam Moss

In a small brick building in the Lower East Side of Manhattan, you can find Adam Moss’s “den of torture.”

Prior to this interview, almost no one has been allowed in.

“Just my husband and my teacher. That’s it.” Moss said. “Two people in my entire life and I’ve had this thing for five years. So welcome.”

This space is less menacing than most dens of torture; there aren’t any medieval instruments of pain after all. Instead, the small, light-filled room overflows with brushes and palettes, and paintings of various sizes and stages of completion rest on every surface.

Adam Moss’ so-called “den of torture.” Instead of Medieval instruments of torture, he has paintbrushes and palettes.

Adam Moss

hide caption

toggle caption

Adam Moss

When Adam Moss gave up his job as editor-in-chief of New York Magazine five years ago, he started painting. He loved it, but it was agonizing.

“I really wanted to be good, and it made the act of making art so frustrating for me,” said Moss. “This [studio] is where I come many days and wrestle with trying to make something.”

Trying to make something is exactly the subject of Adam Moss’s new book, The Work of Art: How Something Comes from Nothing.

“The book is called The Work of Art,” says Moss. “And that is kind of what it’s about.”

It’s about the work.

Adam Moss’ The Work of Art: How Something Comes from Nothing features interviews with more than 40 creatives about their process, from blank page to final product.

Penguin Press

hide caption

toggle caption

Penguin Press

The book has 43 chapters, each one dedicated to a single artist, and their process of creating a single work. They come from a wide range of disciplines. There are poets, painters, chefs, sand castle sculptors and crossword puzzle makers.

And through this collection of interviews, the book tries to answer the questions: How does a sketch become a painting? How does a scribbled lyric become a song? How does an inspiration become a masterpiece?

The book is a visual feast, full of drafts, sketches, and scribbled notebook pages.

A sample of pages from chapter 9 of the book, which profiles poet and essayist Louise Glück.

Penguin Press

hide caption

toggle caption

Penguin Press

A sample of pages from chapter 9 of the book, which profiles poet and essayist Louise Glück.

Penguin Press

Every page shows how an idea becomes a finished design.

In one chapter, Moss speaks with Amy Sillman, an abstract painter who Moss admires for her unique use of color and shape.

“Amy was also a dream subject for this project,” Moss writes. “Because to reach the finish line of most of her paintings, she paints dozens of paintings, or even more, each usually pretty wonderful.”

The chapter contains 39 images, demonstrating the full evolution from first draft to finished product of her work, Miss Gleason.

Each image is accompanied by a quote from Sillman, explaining what step that particular draft represented in her process.

In another chapter, Moss speaks with the musician Rostam, who describes the process of writing the song “In a River.”

Musician Rostam Batmanglij, pictured here performing in 2017, shared his songwriting process with Adam Moss.

Emma McIntyre/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Emma McIntyre/Getty Images

Musician Rostam Batmanglij, pictured here performing in 2017, shared his songwriting process with Adam Moss.

Emma McIntyre/Getty Images

For Rostam, the creative process occurred in large part on his iPhone, in a collection of draft lyrics written in the notes app, and melodies in recorded as voice memos.

Voice memo draft of Rostam’s “In a River”

Eventually, those notes and recording on his phone evolved into a completed song.

Rostam’s animation video for his song “In a River.”

YouTube

So, what is the key to creating a masterpiece? Moss did not find an answer. All of artists featured across the book are unique, and so are their creative processes.

However, Moss did point to some frequently shared traits.

One commonality Moss found was that many artists describe themselves as having ADHD.

“Whether they have ADHD or not, [they have] the elements that we associate with ADHD,” Moss said, describing a balance of distractedness and focus.

“You need to be distracted enough for your mind, for your imagination to go fishing, and you need to be focused enough to know what to do with it.”

Moss also found that his subjects consistently found ways not to let the fear of failure or mistakes prevent them from starting.

“They tried to get through that as quickly as possible and with as little thought as possible,” Moss said. “Many of them write in longhand, giving themselves explicit permission to fail.”

However, there was one trait between Moss’s subjects that was truly ubiquitous.

“They all have a compulsion, an obsession to make something. It gets into their system and they can’t let go of it,” Moss said, explaining that the vision or the final product is secondary to the process.

“The end product is not the point,” Moss said. “what they were consumed by, why they did what they did is because they were consumed by the work. “

Lifestyle

Renowned painter and pioneer of minimalism Frank Stella dies at 87

Frank Stella with one of his works at the Royal Academy’s Summer Exhibition in London in 2000.

Ian Nicholson/PA Images via Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Ian Nicholson/PA Images via Getty Images

Frank Stella with one of his works at the Royal Academy’s Summer Exhibition in London in 2000.

Ian Nicholson/PA Images via Getty Images

Renowned minimalist painter Frank Stella died Saturday of lymphoma at his home in Manhattan, N.Y. The artist was 87 years old.

Stella’s representative, Marianne Boesky Gallery in New York, confirmed the news with NPR.

“Marianne Boesky began representing Stella in 2014, and the gallery is deeply grateful for a decade of collaboration with the artist and his studio,” Boesky said in a statement shared with NPR. “It has been a great honor to work with Frank for this past decade. His is a remarkable legacy, and he will be missed.”

One of the most influential American artists of his time, Stella was a pioneer of the minimalist movement of the early 1960s. During that time, painters and sculptors challenged the idea that art was meant to be representative and used their medium as their message.

Instead of representing three-dimensional worlds through the canvas, some of Stella’s early artworks reflected his desire to have an immediate visual impact upon viewers. A series titled Black Paintings used parallel black stripes to prompt awareness of the painting as a two-dimensional surface. As Stella once gnomically stated, “What you see is what you see.”

Stella’s Die Fahne hoch! (1959) is part of a series of paintings that earned the artist notoriety in the 1950s.

2015 Frank Stella/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Digital Image

hide caption

toggle caption

2015 Frank Stella/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Digital Image

Stella’s Die Fahne hoch! (1959) is part of a series of paintings that earned the artist notoriety in the 1950s.

2015 Frank Stella/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Digital Image

“It was about being able to make an abstract painting that really wasn’t based on anything but the gesture of making itself, which was the gesture of making the painting,” Stella Terry Gross in a Fresh Air interview in 2000.

Frank Stella was born into a middle-class Italian American family. His father was a gynecologist who painted houses during the Great Depression and his mother was a housewife and artist. Young Stella grew up surrounded by paint; amongst his mother’s artworks and helping his father whenever he repainted his own home. “I always liked paint,” he told Gross, “the physicality of it.”

He started exploring paint more professionally when he was in high school in Massachusetts under the supervision of abstractionist painter Patrick Morgan, who taught there. Even while studying history as a Princeton undergraduate, Stella continued taking art classes. Through his Ivy League connections, Stella was introduced to the art world of New York City, which started to shape his early artistic vision as he encountered artists such as Jackson Pollock and Franz Kline, who would become some of his most admired influences.

“I really wanted more than anything to make art that was as good as the good artists were making. I wanted to make art that someday — and I didn’t expect it to be that way right away — that it would be as good as [Willem] de Kooning or Kline or [Barnett] Newman or Pollock or [Mark] Rothko. They were my heroes and I wanted to make art that was as good as them,” he told Fresh Air.

A 2014 sculpture by Frank Stella entitled Inflated Star and Wooden Star in the courtyard at the Royal Academy of Arts on Feb. 18, 2015, in London.

Ben Stansall/AFP via Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Ben Stansall/AFP via Getty Images

A 2014 sculpture by Frank Stella entitled Inflated Star and Wooden Star in the courtyard at the Royal Academy of Arts on Feb. 18, 2015, in London.

Ben Stansall/AFP via Getty Images

When Stella was only 23, he made his debut at New York’s Museum of Modern Art. And soon after his series Black Paintings, which he started in 1958, Stella created two more series, Aluminum Paintings (1960) and Copper Paintings (1960-61), that committed to the idea that the art was in the medium and was, as he told The Guardian in 2015, supposed to be “fairly straightforward.”

In 1970, when he was 33 years old, Stella became the youngest artist ever to receive a retrospective at New York’s Museum of Modern Art. His exhibition covered a decade of his drawings and paintings and emphasized his originality in simplicity.

In the 1990s, Stella’s work evolved from the canvas to colorful geometrical configurations and sculptures. He started using computer technology and architectural rendering to incorporate digital images into his work. His Moby Dick series, a set of paintings, lithographs, and sculptures, took their titles from chapters of Herman Melville’s classic novel. According to the Princeton University Art Museum, the series was Stella’s “most ambitious artistic endeavor … [that] pushes the boundaries between printmaking, painting, and sculpture.”

Visitors walk past the installation The Honor and Glory of Whaling (1991) by Frank Stella in the Folkwang Museum in Essen, Germany, in 2010.

Volker Hartmann/DDP/AFP via Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Volker Hartmann/DDP/AFP via Getty Images

Visitors walk past the installation The Honor and Glory of Whaling (1991) by Frank Stella in the Folkwang Museum in Essen, Germany, in 2010.

Volker Hartmann/DDP/AFP via Getty Images

A straightforward, rather blunt artist, Stella never really cared about what others thought of him — or of his art. But his six-decade career inspired generations of artists, including painter Julie Mehretu. “Once I really started to understand his work and follow it, there’s a certain type of invention and playfulness and extreme rigor with which he kept going forward,” she said in a 2015 NPR interview.

Stella’s numerous awards and accolades included the National Medal of Arts, the country’s highest honor for artistic excellence, in 2009, and the 2011 Lifetime Achievement in Contemporary Sculpture Award from the International Sculpture Center.

Lifestyle

The L.A. laundromat offers something special and rare: a home away from home

The laundromat is the perfect place to cry in public.

I’m here now, crying as I type this. I don’t care who sees me. I’m tucked away into one of the two-person benches between the silver three-load washers, tears welling up in my eyes near their tipping point. I make eye contact with a man who passes me by on his way to the sink. He looks slightly concerned. But even if I wasn’t partially hidden it wouldn’t matter. I feel safe here. It’s a place that puts intimacy on a rush order, past the point of faux social etiquette. I’m surrounded by people who see the color of my underwear as I pull it out of the dryer. What are a few tears at this point? We’re already well acquainted.

I’ve always been too internal for my own good. I cry in public often because of what’s happening in my imagination. And the laundromat — its familiar, sterile smell of cleaning products and metal, the constant chugging sound of water and hot air — is a place that feels particularly primed for me to slip into my subconscious mind, like sliding into a comfortable pool of Jell-O. I remember things I forgot. I romanticize the Krypto Villain stickers in the quarter vending machines. I sit and stare at people until it hurts. I fantasize about what their lives are like, or all the times they wore those nice faded jeans that they’re pulling out of the dryer while the static shocks their skin. I see a couple sitting under the food tent outside. Their knees point into each other’s while they’re eating, and by their body language alone I conclude that they are, of course, in love. I see a teenage boy shadow-boxing the washing machine in what I decide by a demeanor that I find all too familiar, is a bid for attention. I’m reminded of when I was 14 and needed attention.

An L.A. laundromat is always open, and always waiting for you.

The dryer whirs soft, the fluffy smell of chemical flora rises, the badass little kids with silver teeth run circles around their mom while she folds their Spiderman T-shirts. An image flashes in my mind of myself when I was small — curly hair, dirty Osirises and the fake tattoos I got from the quarter machine fading on my forearm, using the laundry cart like a bumper car or laying my head on a freshly baked mountain of clothes that was just piled into it from the dryer.

I love the laundromat. I’ll tell anyone who will listen. You will catch me at a party giving what might as well be a PowerPoint presentation about the joys of the laundromat. What most people see as an undesirable chore I see as a comfort zone. My own private version of the club, where fluorescent light floods from the ceiling and there’s always Amy Winehouse or Salt-N-Pepa playing over the loudspeaker. My local laundromat is open 24 hours — as all the good ones are — and any time of day or night, for the rest of my life, I know there is a place that is open and waiting for me (as long as I have a hoodie to wash). I’ve never had an in-unit washer and dryer in my many years of living on my own. And it never mattered. Because I have something rarer, more special: a home away from home.

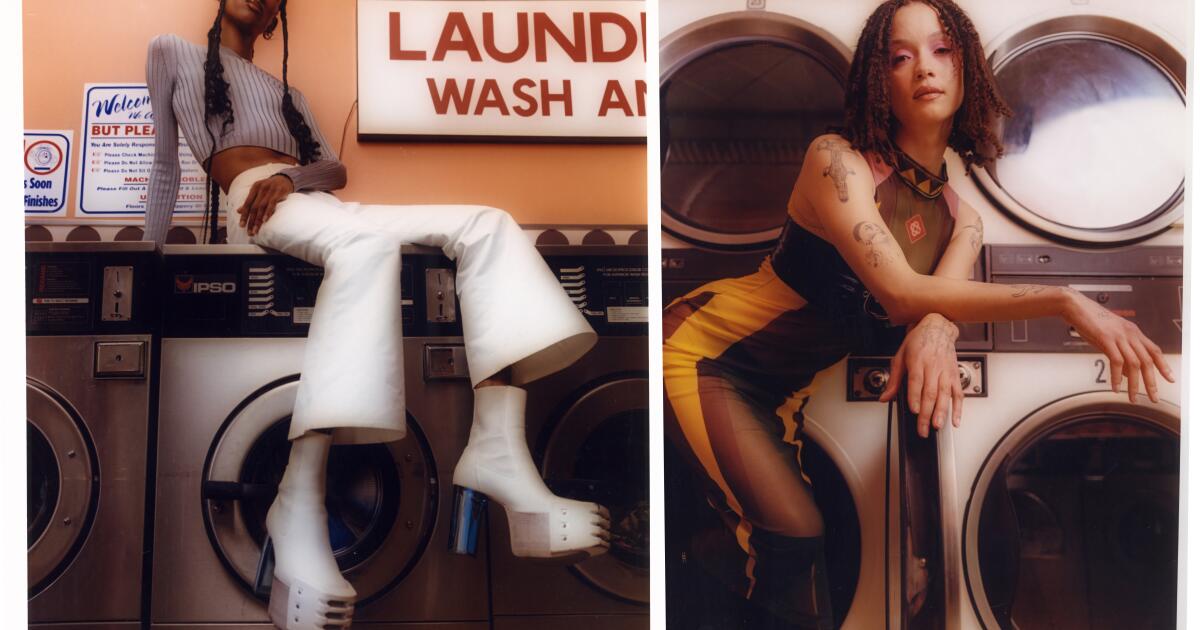

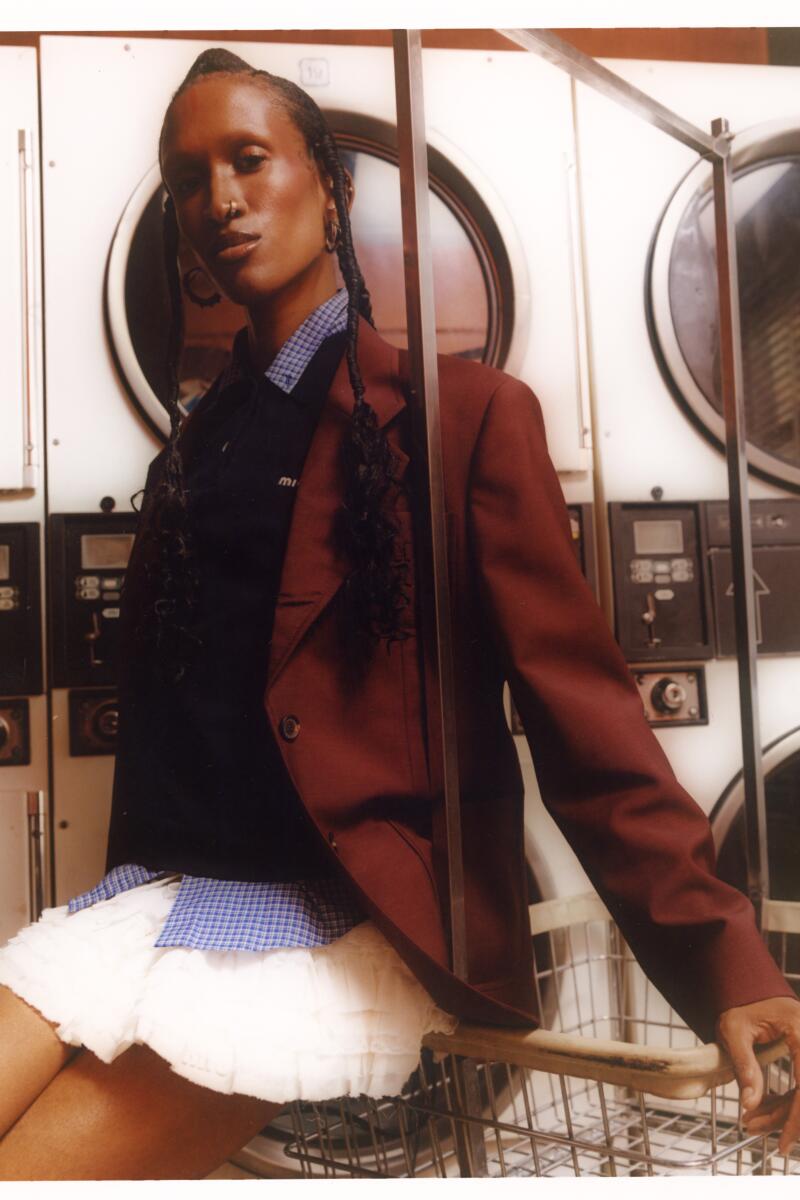

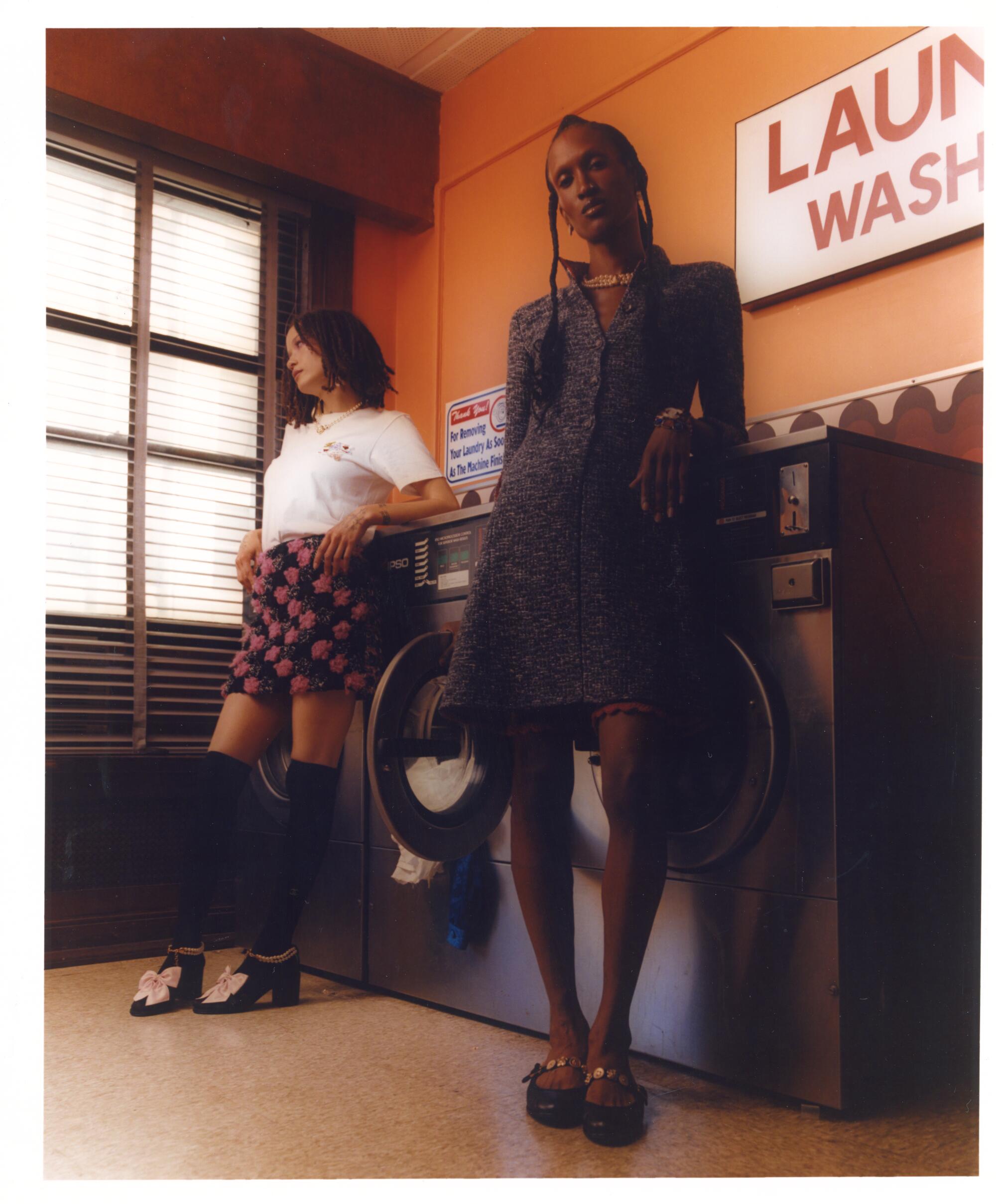

May wears Marni dress, Fendi pink boots.

Maahleek wears Miu Miu, model’s own jewelry.

There’ve been rumblings on the internet lately about “third places” — spots people go to that are not their house, not their office, but a secret third thing. “These places are vanishing!” the TikTok feed will warn. Sociologist Ray Oldenburg coined the term “third place” in his 1989 book “The Great Good Place” and expanded on it in his 2001 book, “Celebrating the Third Place.” Oldenburg’s life’s work has been dedicated to explaining why informal gathering spaces matter, and in his writing he defined some characteristics of a true third place, including low barrier to entry, being a status leveler, somewhere that conversations happen and arguably most importantly, being a home away from home. This, Oldenburg writes, is the antidote to isolation, the lubricant of a healthy social balance. “Y’all got nowhere to hangout and it shows,” stated one TikTok creator, who made a series out of suggesting third places.

The experience of the laundromat spills beyond the confines of its walls into its surrounding areas. If you’re doing laundry in a neighborhood like mine, then you’re very lucky, and every single day there is someone selling food on the sidewalk out front. Last time I was there, it was the new-to-me Colombian spot, a Mexican empanada spot and a birria spot that sells it on top of pizza. The smell of soupy, red meat mixing with the unmistakable perfume of Suavitel and Zote shavings. On the weekends in winter, you’ll find the champurrado lady selling Styrofoam cups of the viscous, steaming drink out of the trunk of her minivan.

The parking lot is where all the good things happen. When I was in my early 20s, I used to put my load in and s**** a b**** with my bestie as I waited for the cycle to finish. It’s where I bought someone’s physical mixtape a couple months ago because I’m a recovering people-pleaser, and was in partial system shock from even seeing a physical mixtape. It’s where I can never find parking — even on a weekday evening — because as long as there are days to live there will be laundry to do.

The number of activities done there that have nothing to do with washing your clothes feels specific, in a lot of ways, to L.A. We do all of our photo shoots for our merch brands at laundromats (who among us?), throw experimental punk shows, come up with our best ideas. In my Notes app earlier this year I wrote: “Laundromat culture — places of business and life and love and food.”

I saw a post about a guy who lived in a renovated laundromat in Queens, which felt right to me — something to aspire to. In “The Great Good Place,” Oldenburg writes that third places should inspire the same fuzzy, warm glow of belonging as its inhabitants might find in their own homes. There should be a sense of ownership, of taking up space. I remember this when I Zelle the guy with the Colombian hat $6 for two potato and cheese empanadas. As I sit outside to eat them I notice a parked car with the driver and passenger seats reclined all the way back, two people with their feet up on the dash hold hands as they engage in a romantic, mutual endless scroll on their phones. “That’s beautiful,” I think. We make ourselves at home in places where we need to pass time. We find ways to be comfortable, to turn it into our living room.

Maahleek and May wear Chanel.

When my mom comes to visit me she always takes a load of my laundry to wash at the laundromat I’m at now. (Yes, I’m 29, but her love language is “acts of service,” so sue me.) Every time, she comes back upstairs to my apartment with freshly folded T-shirts (and a blouse she shouldn’t have put in the dryer but did anyway) and regales me with a new story of an hourlong conversation she had with a stranger — the latest in her laundromat saga. I’m more the observant type. The interactions I usually have here are swift, but I still find them deeply meaningful. I notice a lady selling intricate gold-plated rings on one of the tables by the window, the natural light bouncing off the metal tray as the afternoon sun makes its descent. I ask her about them. All of these little moments fill me with the feeling of being human. There is so much talk about a need for connection, a need for community, but no one wants to spend an hour of their week philosophizing intense beauty in the mundane at their local laundromat, do they? That’s what I thought.

An important part of the laundromat experience is the massage chair. It’s the only spot that offers a soft surface to sit inside the actual building, and treating oneself feels right in a place like this. I sit in it long enough before it yells at me to put money in — I never get the actual massage, of course. I get up and relocate to a spot where I can watch the meticulous dance of a big family folding their clothes. They always have, like, 15 kids and 10 loads of laundry — an assembly line that communicates: We ain’t new to this. They quickly take up an entire counter and move with accuracy. I see one family bring a mega Tupperware container filled with hangers, attaching each of their nice button-up shirts like clockwork. It’s hypnotizing. I spot a long chartreuse dress with a flower detail that I would never wear but am deeply intrigued by. In the background, there are moments of intensity that bubble up and dissipate — a rush will be interspersed with serene moments — mimicking the flow of anything else in life.

And as soon as I slipped too deep, I’m jolted back to reality by two women arguing over a dryer, which is a normal interaction here. It went on for 15 minutes, each one of them throwing strays long after the initial confrontation was finished. Draaaaama, I thought. And I laugh to myself. Because that’s what happens when you’re comfortable, when you’re at home, when you’re with your family.

Production: Mere Studios

Models: Maahleek, May Daniels

Makeup: Selena Ruiz

Hair: Adrian Arredondo

Photo Assistant: Dillon Padgett

Styling Assistant: Deirdre Marcial

Lifestyle

'Zillow Gone Wild' brings wacky real estate listings to HGTV

The Golden Saxophone House, featured on HGTV’s new series Zillow Gone Wild.

HGTV

hide caption

toggle caption

HGTV

The Golden Saxophone House, featured on HGTV’s new series Zillow Gone Wild.

HGTV

The real estate social media space is packed with influencers focusing on specific niches like luxury mansions, mid-century moderns or inexpensive yet promising fixer-uppers.

Within this crowded universe, Zillow Gone Wild is a place to go if you’re in the market for, say, a home in Kansas City, Mo., shaped like a UFO; a striking, angular residence in Kalamazoo, Mich., designed in the late 1940s by Frank Lloyd Wright; or a recently built cruise ship with close to 3,000 bedrooms. (Yes, there is an actual Zillow listing for this property.)

“Waking up to an ocean view in the actual ocean is the new best way to wake up,” says Samir Mezrahi, Zillow Gone Wild‘s creator, in his deadpan TikTok commentary on this particularly mind-boggling property listing.

Mezrahi’s prominent account, which has several million followers across platforms, has now been spun off into an equally wild reality TV show. The nine-episode series premiered on HGTV Friday, and is out now on Max.

As on social media, the Zillow Gone Wild TV show is aimed at a general audience and focuses on homes that defy everyday expectations in some way — whether visible from the outside in the architecture, or hidden inside as part of the home decor.

“It has to be something we’ve pretty much never seen before,” says Mezrahi, a former social media director at Buzzfeed, in an interview with NPR.

Setting a “wild” tone

The first segment of the first episode sets the tone: Homeowner Andrew Flair shows off the converted U.S. military missile launch facility in York, Neb. The unusual property has very thick steel doors and no windows.

The exterior of a home converted from a disused missile solo in York, Neb.

HGTV

hide caption

toggle caption

HGTV

The exterior of a home converted from a disused missile solo in York, Neb.

HGTV

“It’s all underground, covered in concrete, and if, for some reason, a bomb goes off, you’ll be safe,” Flair says on the show.

And in episode three, homeowner Kitty Reign tours viewers around the Pirates of the Caribbean-themed residence in Las Vegas she’s selling. This swashbuckler’s paradise comes with a decorative wooden helm (“Everybody plays with it!”) and a tavern (“Kind of our own little secret pirate nightclub!”)

Hosted by comedian Jack McBrayer, who played Kenneth in 30 Rock, the show features 24 homes from around the country either up for sale or recently sold. But only one of them will be crowned the country’s “wildest” at the end of the series, as assessed by HGTV executives. Viewers who correctly guess the winning home can enter a pool for the chance to win $25,000.

Kitty Reign and her wife, Jennifer, show host Jack McBrayer around their Pirates of the Caribbean-themed house, as seen on HGTV’s new series Zillow Gone Wild.

HGTV

hide caption

toggle caption

HGTV

Kitty Reign and her wife, Jennifer, show host Jack McBrayer around their Pirates of the Caribbean-themed house, as seen on HGTV’s new series Zillow Gone Wild.

HGTV

The judging criteria include creativity, commitment to a concept or theme and a quality McBrayer describes as “wackadoo.”

“That special thing that sets this property apart,” says McBrayer on the show. “We reward impracticality.”

The growth of an American pastime

Ogling real estate listings on social media has become an enormously popular American pastime in recent years. Saturday Night Live even did a skit about the trend in 2021. (“The pleasure you once got from sex now comes from looking at other people’s houses.”)

Saturday Night Live produced a skit lampooning the trend for browsing real estate listings on social media in 2021.

YouTube

Mezrahi, who’s based in New York, says he has long made a hobby of idly browsing Zillow. He started Zillow Gone Wild as a side project in the fall of 2020, knowing it would probably catch on. Mezrahi initially launched it only on Instagram, but soon expanded his offering to Facebook, Twitter, TikTok and a newsletter.

“It was, like, prime pandemic. Everyone’s working from home. Companies are saying you can live wherever you want,” Mezrahi says. “So people are moving, thinking about moving, or browsing Zillow just as a bored-on-your-phone thing. So I kind of felt like there was an audience of people out there that are also doing this.”

The rise of TV and online channels devoted to home buying and home improvement, together with the increasingly elaborate social media presence of individual real estate brokers promoting their listings, have further fed the trend.

“This is a time when a lot of people are thinking about where and how we want to live,” says Zillow’s home trends expert, Amanda Pendleton, in an interview with NPR. “And these social media accounts captured our imagination and redefined what a home can be.”

“Wild” listings can be challenging for real estate brokers

That “imagination capturing” quality is what makes Zillow Gone Wild so compelling on TikTok and TV.

But when it comes to actually selling a property, eccentric architecture and festive home decor aren’t necessarily virtues.

“As a real estate broker, you kind of get nervous about that, because the resale value is not the greatest when you’re making it your own,” says San Francisco Bay Area-based realtor Ria Cotton in an interview with NPR. “It may not be liked by other people.”

Host Jack McBrayer taking in the sights of the “Golden Saxophone House.”

HGTV

hide caption

toggle caption

HGTV

Host Jack McBrayer taking in the sights of the “Golden Saxophone House.”

HGTV

While having a marketable property is preferable, Cotton admits the popularity of social media accounts like Zillow Gone Wild shows there’s a growing appetite among homebuyers and potential homebuyers for the “wackadoo.”

“I think more and more people are kind of bored of the cookie-cutter way of doing things,” Cotton says.

Case in point: An unusual music-themed home in Berkeley, Calif., that Cotton recently brokered, featured in Zillow Gone Wild.

The facade of the “Saxophone House” is dominated by two massive, gold saxophone-shaped columns. On the TV show, new homeowner Adanté Pointer proudly shows off the gold treble clef ornaments on the balcony railings indoors.

“The gold accents really make it stand out,” Pointer says appreciatively.

The smooth jazz vibes and bling of the Saxophone House might not be for everyone. But Pointer says it’s perfect for him.

“I am an attorney, and oftentimes, people come to me to make a statement on their behalf,” he says on the show. “And when you look at the outside of this home, it’s definitely a statement piece.”

In an interview with NPR, TV show host McBrayer says if visiting all of the homes featured in the Zillow Gone Wild TV series taught him anything, it’s that even the wildest of homes won’t sit empty forever.

“For every house out there that is just head-to-toe rainbow-colored, there is going to be a buyer. For every home that is attached to the underside of a bridge, there’s going to be a buyer,” McBrayer says. “There’s a lid for every pot.”

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoFirst cargo ship passes through new channel since Baltimore bridge collapse

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoHaiti Prime Minister Ariel Henry resigns, transitional council takes power

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoSpanish PM Pedro Sanchez suspends public duties to 'reflect'

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoAmerican Airlines passenger alleges discrimination over use of first-class restroom

-

Movie Reviews1 week ago

Movie Reviews1 week agoAbigail Movie Review: When pirouettes turn perilous

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoEU Parliament leaders recall term's highs and lows at last sitting

-

Science1 week ago

Science1 week agoMosquito season is upon us. So why are Southern California officials releasing more of them?

-

Movie Reviews1 week ago

Movie Reviews1 week agoCity Hunter (2024) – Movie Review | Japanese Netflix genre-mix Heaven of Horror