Lifestyle

I stopped driving on L.A.'s chaotic freeways. How do I get over this painful anxiety?

My New Year’s resolution this year is simple. This weekend — my first back in L.A. after visiting family for the holidays — I will drive to the 101 freeway entrance by my house and I will … get on it.

Simple as that. But far easier said than done.

I haven’t driven on the freeway in more than two years — I’ve been too afraid. I’ve rarely even ridden as a passenger on the freeway, with someone else behind the wheel, and when I do, I sit on my hands so my fingers won’t tremble.

Fear of driving on the freeway is hardly uncommon — and for good reason. Headlines reporting fatal accidents and police pursuits ending in deadly crashes are more commonplace than ever in L.A.

But here’s the thing: It’s an entirely new phenomenon for me. Living in Los Angeles as a journalist, I’ve fearlessly traversed the city’s vast thicket of freeways for decades. My work took me from the mountains to the desert to the sea. Years ago, I dated someone in San Diego and endured the three-hour drive on the 5 south every other Friday for about a year. And all with relative ease.

So what changed? My brain, basically.

The pandemic was rough, in infinitely varied ways, for everyone. For me, on top of the stresses of the public health crisis and its myriad economic and social repercussions, I experienced a series of losses in succession, sometimes with just weeks between them. And it didn’t let up for about two years. My grief manifested on the freeway, where I’d have small, then more pronounced, panic attacks — something totally new to me.

Here’s what happened: In early 2020, a sibling of mine tragically died. Later that year, my partner and I broke up. We’d been together for several years and it was a significant loss. This was in the early days of the pandemic, when many of us were wiping down our groceries and staying inside for days on end. I was doing that too, but now alone in my apartment.

I don’t have children but my cats provided comfort during that period. (For some of us, our pets are our kids.) Then they both died too, one after the other — unexpectedly. The first, only 8 years old, suffered a violent and painful death. My second cat, much older and more fragile, witnessed it and became so anxious afterward that she got sick and passed away only months later.

The silence in my home, after that, was unsettling: no scritch-scratching of claws on hardwood floors or chomping of kibble in the background as I pecked away at my keyboard writing articles. I’d sip coffee in the mornings, taking some comfort in the lush view of the greenery on my deck. Until nearly all the plants died in a heatwave.

Then my parked car was smashed during a hit-and-run. Insurance paid to fix it. But then the car was targeted by catalytic converter thieves. Again, insurance covered the repairs. But when, several months later, the thieves struck again, my insurance company declared the 14-year-old Honda a total loss.

When the tow truck came to haul my car away, I fell into the driver’s burly arms and cried. I’d had that trusty, beat-up Honda longer than any romantic relationship, and at that moment, it felt like all I had left.

Given this sustained succession of emotional gut punches, my central nervous system was on high alert. A car door would slam outside and I’d jump, my body bracing tensely: “What next?”

That feeling manifested — exaggeratedly so — driving on the freeway. I held it together in all areas of my life, but the freeway became a release valve for my pent-up grief. Instead of seeing the big picture while driving, getting into the flow of traffic, I saw too much detail. The freeway was a dangerous, kinetic collage of spinning wheels and whirling, sparking hubcaps and rectangular hunks of metal flying forward, any piece of which, at any instant, could crash into me. It was like at the start of a billiard game, when the cue breaks the racked balls with a fiery crack, sending the multicolored striped and solid orbs flying in all directions. That’s how I saw traffic. Panic.

The freeway was a dangerous, kinetic collage of spinning wheels and whirling, sparking hubcaps.

The lane I was driving in felt constricting and narrow; trucks on either side of me felt hulking and ominous. My jaw clenched, my breath quickened, my teeth chattered. And my heart pounded in my chest.

It wasn’t a choice so much as survival — I could not drive, safely, on the freeway anymore. I made adjustments, slipping like water around rocks. I changed my Waze settings to “avoid freeways” and took surface streets everywhere instead. I took Ubers or carpooled with friends if the drive was too long on surface streets. If headed especially far, I took a train.

I should add that I don’t particularly like to drive. Nor would anyone close to me say I’m good at it. Before L.A., I’d only lived in walkable cities with active public transportation systems: Philadelphia, San Francisco, Tokyo, Boston. But I certainly never feared driving.

And for those who have always feared freeway driving, it’s understandable. Traffic-related deaths in Los Angeles have been on the rise in recent years, at their highest point in two decades. In 2022, 312 people died in traffic accidents, according to the Los Angeles Police Department’s most recent data. That’s a 5% jump from 2021 and a 29% jump from 2020.

Perhaps the most disconcerting part was that my newfound freeway phobia sparked something of an identity crisis: I am not a fragile or fearful person. I take risks, I speak up for myself, I have a sense of agency. I don’t recognize this new, tentative version of myself. I’m confused by her, ashamed. Who is she? How do I get back to the self I identify with? Does she even still exist?

I’ve since healed from those aforementioned losses and am feeling infinitely revived in my personal life. New cats, new boyfriend, new car. But, oddly, the freeway fear has stuck.

“It’s such a normal human impulse when you’ve gone through tragedy and loss,” says L.A. author and psychotherapist Claire Bidwell Smith. “You’re seeing the world through a lens where the unexpected looms around every corner and something catastrophic can happen at any moment. Your life was going along and then: Bam! Bam! Bam! You’re scrambling to hold onto something, so you hold onto ‘How can I predict this, control it in some way?’ But we can’t control the world in the way we would like to, so we get stuck in this catastrophic place.”

Panic attacks in cars are especially common, Bidwell Smith adds. Her theory? “The car is a space where you’re often alone, a quiet private space, and all these thoughts, some of the stuff we’ve been pushing away, start to gurgle up.”

I haven’t talked openly about my freeway phobia much, not even to family. Until recently — and nearly everyone I’ve spoken to about it had experienced something similar or knew someone who had. I was at dinner recently with two journalist friends. One of them said she developed flying anxiety after her father died, something that dissipated over time. The other said her sister in Toronto developed a fear of driving on the freeway after their father died — she still hasn’t gotten over it.

Bidwell Smith says that after her own parents died, she developed a fear of flying and became fixated on her health. A client developed a fear of riding on elevators after his wife died.

How many more people are there like us in L.A.?

“It’s very common,” says Sarah Caliboso-Soto, director of the Telebehavioral Health Clinic at USC’s School of Social Work, which provides counseling for driving anxiety among other mental health issues. “Grief itself can be a very traumatic experience, and when people are driving, in particular, their senses are more heightened. And you can experience anxieties as a result.”

My period of avoiding freeways wasn’t all bad. I traversed neighborhoods I’d never otherwise pass through in L.A., gaining a better understanding of how the city connects. I got lost plenty, on zigzaggy Waze routes, but that had its upsides too. I stumbled on a collection of street murals, on remote side streets, in the downtown L.A. warehouse district. I found an available apartment for rent, for a friend, in Jefferson Park, a gem of a neighborhood filled with old Craftsman homes. I stopped several times for roadside fruit at different points around the city, wolfing down chili-spiked mango, drenched in lime juice, from behind the wheel.

But I long for my freedom again, to be unhindered by an emotional impediment. I miss the person I once was and ache to embody her again. It may not happen all at once; likely it will be a slow process, one freeway ramp at a time.

Lifestyle

Country Joe McDonald, anti-war singer who electrified Woodstock, dies at 84

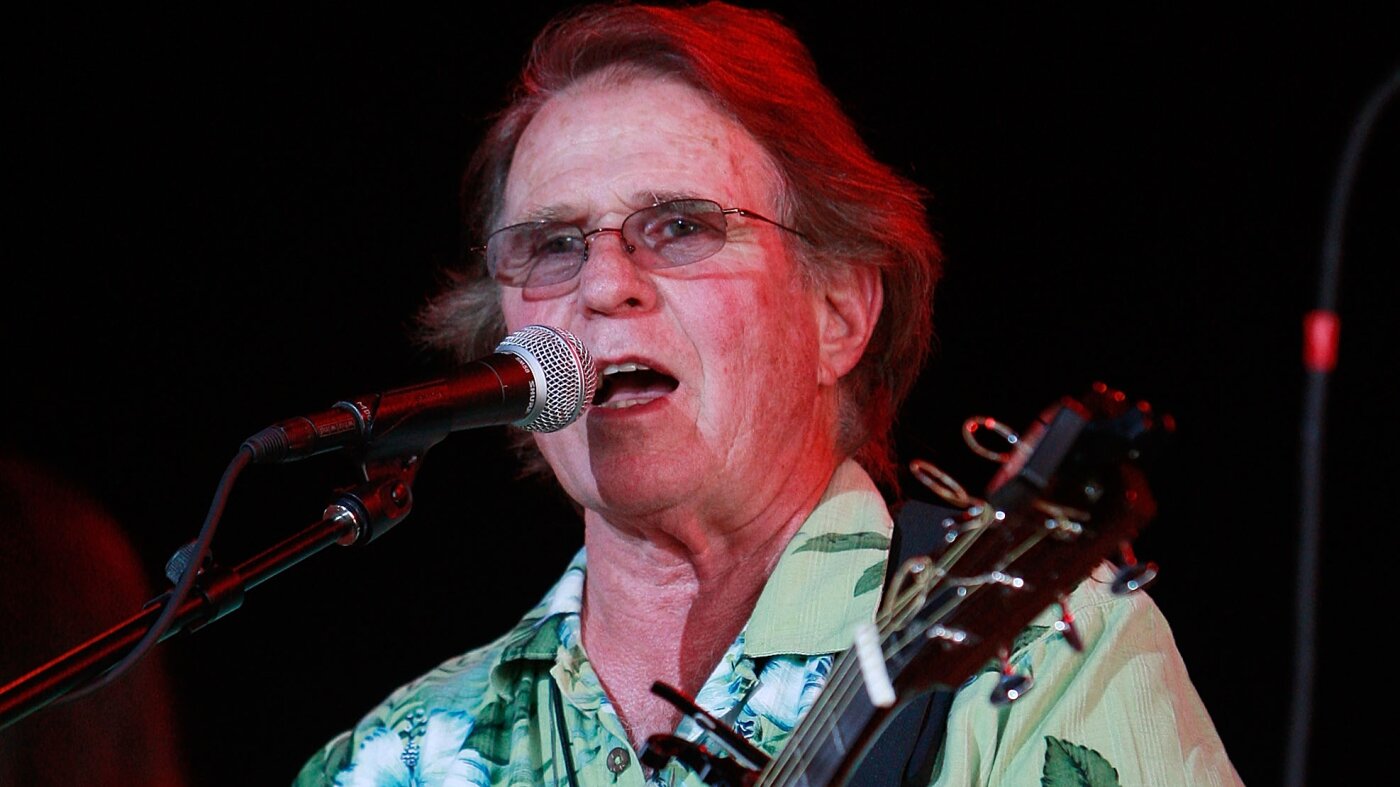

Singer Joe McDonald sings during the concert marking the 40th anniversary of the Woodstock music festival on Aug. 15, 2009 in Bethel, New York. McDonald has died at age 84.

Mario Tama/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Mario Tama/Getty Images

Country Joe McDonald, the singer-songwriter whose Vietnam War protest song became a signature anthem of the 1960s counterculture, has died at 84.

McDonald died on Saturday in Berkeley, Calif., according to a statement released by a publicist. His health had recently declined due to Parkinson’s disease.

Born in 1942, in Washington, D.C., he grew up in El Monte, Calif., outside Los Angeles, according to a biography on his website. As a young man he served in the U.S. Navy before turning to writing and music during the early 1960s, eventually becoming involved in the political and cultural ferment of the Bay Area.

In 1965 he helped form the band Country Joe and the Fish in Berkeley. The group became part of the emerging San Francisco psychedelic music scene, blending folk traditions with electric rock and pointed political commentary.

The band’s best-known song, “I-Feel-Like-I’m-Fixin’-to-Die Rag,” captured the growing anti-war sentiment of the Vietnam era. With its ragtime-influenced rhythm and sharply satirical lyrics about war and political leadership, the song quickly became associated with protests against the conflict.

McDonald delivered the song to some half a million people at the 1969 Woodstock festival in upstate New York. Performing solo, he led the crowd in a form of call-and-response before launching into the anti-war anthem, turning the performance into one of the defining scenes of the festival.

Country Joe and the Fish released several recordings during the late 1960s and toured widely, becoming closely identified with that era’s West Coast rock and protest movements.

McDonald later continued performing and recording as a solo artist, recording numerous albums across a career that spanned more than half a century. His work drew variously from folk, rock and blues traditions and often reflected his long-standing interest in political and social issues.

Although he became widely known for his opposition to the Vietnam War, McDonald frequently emphasized respect for those who served in the U.S. military. After his own service in the Navy, he remained engaged with veterans’ issues and occasionally performed at events connected to veterans and their experiences, according to his website biography.

Lifestyle

Country Singer Maren Morris Tells Donald Trump Supporters ‘You Voted For This’

Maren Morris to Trump Voters

You Got Bamboozled!!!

Published

Country music star Maren Morris is speaking her mind about what she sees as the failures of the Trump administration, and she doesn’t care if she loses fans over it.

According to Maren Morris, if you supported Donald Trump in his presidential elections, you voted for a “dementia ridden, diaper clad, cornball” and “you got bamboozled.”

Not only that … she doesn’t feel bad for the MAGA faithful who may feel disillusioned by their leader.

In a TikTok posted Friday, she said, “The is literally the result of ploying and voting for losers.”

Morris has expressed her dismay at music becoming so political since she’s jumped onto the scene — something she’s benefitted from due to songs like “My Church” — but she’s clearly not shy about her views.

“If you don’t agree with me … you can’t enjoy my music because of my viewpoints? You’re absolutely allowed to do that,” she said. “But I am only here for an iteration of revolutions around the sun, a couple, and so I do feel like I have sacrificed a lot of my mental health, my financial standing, my family, just because I am so deeply concerned and uncomfortable with the weird status quo of country music.”

Lifestyle

Photos: These bold women stand up for justice, rights … and freedom

Jean, 72, a Chinese opera performer, poses for a portrait before performing in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

Annice Lyn/Everyday Asia

hide caption

toggle caption

Annice Lyn/Everyday Asia

March 8 is International Women’s Day — a date picked in honor of a remarkable Russian protest.

During World War I, women in Russia went on strike. They demanded “bread and peace.” Among the results of their four-day protest: the Czar abdicated and women gained the right to vote.

This bold strike began on Feb. 23, 1917, according to the Julian calendar then used in Russia. That date translated to March 8 in the Gregorian calendar that much of the world uses. So that’s the day chosen for this celebratory event.

True to the spirit of those Russian women, the world pauses on this day to celebrate the achievements of women. This year to mark International Women’s Day, the United Nations is calling for “Rights. Justice. Action. For all women and girls.”

Sometimes, the true achievements are the ones that we barely see. The photographers at The Everyday Projects, a global photography and storytelling network, have shared portraits of women who in ways large and small are determined, like those Russian women over 100 years ago, to improve the lives of women and to build a better world.

Singing with strength

Kuala Lumpur-based photographer Annice Lyn likes to highlight the strength, resilience and the stories of women who are often overlooked.

That’s the inspiration for her portrait of Jean, 72, as she prepares for a performance of Chinese opera at Kwai Chai Hong, a restored heritage alley in Kuala Lumpur’s Chinatown in August 2024.

Such performances, typically staged during festivals and temple celebrations, combine singing, acting, martial arts, elaborate costumes and symbolic makeup to tell classical stories from Chinese folklore, history, and literature.

“Performers like Jean often dedicate decades of their lives to mastering this art form, preserving techniques and stories that are centuries old,” says Lyn. They told her that they may encounter negative reactions — questions like “are you wasting your time” or simply indifference.

“Sustaining a centuries-old practice in a modern urban setting requires both resilience and passion,” says Lyn, who made this picture minutes before the performance. “I wanted to give Jean the dignity she deserves through this portrait, a strong, intimate image that acknowledges her beauty, her discipline and the life she has dedicated to Chinese opera. I hoped to make her feel seen and heard, capturing not just a performance but a living cultural legacy.”

Dreaming of a toilet

Nkgono Selina Mosima, a resident of Thaba Nchu, Free State, South Africa, has hoped for years that she could afford to dig a pit toilet in her yard.

Tshepiso Mabula/The Everyday Projects

hide caption

toggle caption

Tshepiso Mabula/The Everyday Projects

The subject is Nkgono Selina Mosima, a resident of Thaba Nchu, Free State, South Africa, a region where poverty is rampant, Mosima is one of many residents who lack proper sanitation, says Tshepiso Mabula, a photographer and writer based in Johannesburg. Her wish was to hire someone to dig a pit toilet in her yard – in which human waste is collected in a pit and allowed to break down naturally over time – but she couldn’t afford the cost. The alternative is open defecation – finding a secluded place despite the personal risks and the potential health consequences of untreated human excrement.

“I was drawn to Nkgono by her unrelenting faith and positive outlook; despite her difficult circumstances, she constantly reiterated her hope that things would improve,” says Mabula. “This inspired the framing of the portrait: the bright colors, her headscarf and the belt around her waist all serve to highlight her strength, optimism and faith.”

The picture was taken in 2020. Today, Mabula says, many women still lack safe and effective sanitation options. Nkgono was a powerful voice for action and change as she eventually could afford to dig a pit toilet on her property.

Russian footballers

These women from Voronezh, Russia, participated in the country’s short-lived but intense American-style football league. They’re hanging out in the locker room.

Kristina Brazhnikova/Everyday Russia

hide caption

toggle caption

Kristina Brazhnikova/Everyday Russia

It seems improbable — starting an American football league for women in Russia. Not soccer but football. That’s what Portugal-based photographer Kristina Brazhnikova is documenting in her project “Mighty Girls,” which she shot between 2018 and 2021.

Any Russian woman could join, regardless of age, body type or level of training, she says. Coaches from the U.S. women’s national football team participated.

In the photo, the girls from the Voronezh team “Mighty Ducks” (Gabi, Katya, and Olesia) are in the locker room of a training camp preparing for practice. Team members came up with the name, she says.

“Everything was built on enthusiasm, so the players had to study the rules and playbooks on their own. Some women were invited by friends, others were drawn to the unusual nature of the sport, and some simply wanted to improve their physical fitness,” says Brazhnikova, who is Russian herself.

After the first practice, many women decided the game wasn’t for them, she says. It requires not only strength and endurance but the ability to memorize complex plays. Players had to buy their own protective gear, pay for field rentals and cover their travel expenses to competitions in other cities.

“Those who stayed, however, found a new family,” says Brazhnikova — and a new form of expressing emotions, including aggression. The women told her that playing American football made them braver and more decisive. They allowed themselves to step outside their comfort zones and push beyond the limits of their usual lives. They changed jobs and left relationships that had run their course. And the sound of pads colliding on the field became their favorite,” she says.

The league ceased to operate in 2022.

Hunting for missing loved ones

Hilaria Arzaba Medran of Mexico stands with tools she’ll use as she searches a clandestine burial site for the grave of her son, Oscar Contreras Arzaba, who disappeared in 2011 at age 19.

James Rodríguez/Everyday Latin America

hide caption

toggle caption

James Rodríguez/Everyday Latin America

Hilaria Arzaba Medran, 57, is no stranger to loss. Her son Oscar Contreras Arzaba disappeared on May 22, 2011, at the age of 19. A resident of the Mexican state of Veracruz, she’s a member of Solecito, an organization whose 250 members go out and look for their missing relatives on a regular basis. Holding tools in this photograph taken in Feb. 20, 2018, she searches for her missing son and other victims in a location known to have served as a clandestine grave.

“This collective is primarily led by women, and I was awe-struck by their determination to find their loved ones despite horrific violence and real-life threat to their own well-being,” says photographer James Rodríguez.

On this occasion in 2018, Rodriguez and others in the group had received an anonymous tip of a possible clandestine cemetery on the outskirts of Cordoba. She went searching with several other collective members, digging tools in hand. “We went into an isolated rural field that felt macabre in itself and [we] had no sort of security personnel with us. I was truly astounded by their conviction and courage,” he says.

A demand for housing

Janaina Xavier, a community leader, holds her son in a building in São Paulo, Brazil, that was occupied by people without housing in 2024.

Luca Meola/Everyday Brasil

hide caption

toggle caption

Luca Meola/Everyday Brasil

Janaina Xavier, a community leader, holds her son while looking out the window of the building where she lives with six of her 10 children near the Cracolândia district in São Paulo, Brazil, on April 23, 2024.

She currently serves as a council member for the Coordination of Policies for the Homeless Population and advocates for the rights of people living in and around Cracolândia.

“I’ve known Janaina Xavier for many years, since I began my long-term work documenting Cracolândia in São Paulo. She has long been involved in struggles for housing rights for people living in this highly stigmatized region of the city,” says photographer Luca Meola.

This photograph was taken inside a building being illegally occupied by Xavier and dozens of other families – a way for them to secure housing in the city center.

“For many low-income families, occupying empty buildings is one of the only ways to remain in the central area and access essential services and work opportunities,” Meola says.

In 2025, the city evicted Xavier, her family and the other residents.

The mother leaders of Madagascar take charge

In the Grand South of Madagascar, women known as “reny mahomby,” or mother leaders, perform a welcoming dance before starting a session to teach women in the community how to improve their lives.

Aina Zo Raberanto/The Everyday Projects

hide caption

toggle caption

Aina Zo Raberanto/The Everyday Projects

In this photo from the Grand South of Madagascar, in Amboasary Sud, women known as “Reny Mahomby,” or “mother leaders” perform a welcoming dance.

The “mother leaders” inspire other mothers in the community to make changes in their lives – to improve hygiene, to educate their children, to start small businesses, says photojournalist Aina Zo Raberanto, who lives in this African island nation but had never before visited the Grand South.

The dance took place at the start of a training session, says Raberanto. In this photo from November 2021, she says. “These mother leaders welcome us with a traditional dance from the region. I was deeply moved by their commitment to their community.”

The mothers of Madagascar “are the pillars of the household while sometimes facing difficult realities such as violence or early marriage,” she says. “I took this photograph to show both their strength, their dignity, their joy for life and the warmth of their welcome despite the hardships. Behind their smiles and movements lies a great determination to continue supporting their families and to build a better future for their children.”

Marching for their rights

Members of Puta Davida, a feminist collective advocating for the labor and human rights of sex workers, take part in a march during Carnival in downtown Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, on Feb. 14, 2026.

Luca Meola

/Everyday Brasil

hide caption

toggle caption

Luca Meola

/Everyday Brasil

This photograph was taken during Carnival in Rio de Janeiro this February.

“I have been accompanying the collective Puta Davida for about three years. [It] works to create public debate around sex work, advocating for the recognition of sex work as legitimate labor and for the protection of sex workers’ human and labor rights,” says photographer Luca Meola.

The Puta Davida is a feminist collective from Rio de Janeiro created in the early 1990s by the sex worker and activist Gabriela Leite, a historic figure in Brazil’s movement for sex workers’ rights.

“I have been accompanying the collective for about three years. [It] works to create public debate around sex work, advocating for the recognition of sex work as legitimate labor and for the protection of sex workers’ human and labor rights,” says photographer Luca Meola.

In 2026, one of the community organizations that prepares music, dance, and large performances for Carnival parades chose to dedicate its parade to sex workers

Meola, who photographed the members of this group as they marched, says: “For me, what is powerful about this moment is how these women reclaim visibility in public space. Through political organization, performance and collective presence, they challenge stigma and assert their rights — which I believe strongly resonates with this year’s theme [for International Women’s Day] of justice and action,” says Meola.

Kamala Thiagarajan is a freelance journalist based in Madurai, Southern India. She reports on global health, science and development and has been published in The New York Times, The British Medical Journal, the BBC, The Guardian and other outlets. You can find her on X @kamal_t

-

Wisconsin1 week ago

Wisconsin1 week agoSetting sail on iceboats across a frozen lake in Wisconsin

-

Massachusetts6 days ago

Massachusetts6 days agoMassachusetts man awaits word from family in Iran after attacks

-

Maryland1 week ago

Maryland1 week agoAM showers Sunday in Maryland

-

Florida1 week ago

Florida1 week agoFlorida man rescued after being stuck in shoulder-deep mud for days

-

Pennsylvania4 days ago

Pennsylvania4 days agoPa. man found guilty of raping teen girl who he took to Mexico

-

Oregon1 week ago

Oregon1 week ago2026 OSAA Oregon Wrestling State Championship Results And Brackets – FloWrestling

-

News1 week ago

News1 week ago2 Survivors Describe the Terror and Tragedy of the Tahoe Avalanche

-

Sports4 days ago

Sports4 days agoKeith Olbermann under fire for calling Lou Holtz a ‘scumbag’ after legendary coach’s death