Lifestyle

Grief changes you. Michael Arceneaux is writing through it

Michael Arceneaux at the Hollyhock House. Arceneaux wears Loewe shirt, Isabel Marant denim jeans and jacket, Louis Vuitton shoes, Akoni glasses.

(Gabriel S. Lopez/For The Times)

Forty-eight hours of torrential downpour betray the natural logic of Los Angeles. Submerged roadways, mudslides and record-setting rainfall have transformed the Southland city into an obstacle course out of the apocalypse, the very scene you’d see in a movie before everything goes full dystopia. Withstanding extreme conditions is nothing new for Michael Arceneaux, who has made a career out of navigating unstable ground. Today is just another Wednesday.

As we sit to talk on the balcony of his Koreatown apartment, seven stories up, the rain has finally stopped despite a procession of chubby gray clouds that hang like prop art in the sky, threatening to disrupt what momentary peace we’ve found. For now the storm is over. The context is appropriate given what Arceneaux, 39, has faced in the last year, losing his mother to cancer in October. And a close friend before that. “I am in my sad boy era,” he jokes.

I want to tell him that storms don’t last forever but people in the midst of intense grief don’t need cheesy Hallmark cliches. Instead, I promise to listen and be there for him. It has been a great fortune of mine to call Michael a friend since 2004. The orbit of our friendship began that summer, before either of us made it as writers, and what I knew of him then is even more vivid and electric now: He is as genuine, witty and insightful as they come.

“Grief is just a really uncomfortable subject.”

— Michael Arceneaux

Michael grew up the middle child in a subdivision of Houston named Windsor Village. He attended Howard University, where he studied broadcast journalism, and later started the Cynical Ones, a blog that earned him the reputation as an original voice on matters of race, politics and pop culture. He’s written for just about everybody — the Washington Post, Rolling Stone, the New York Times, Ebony, Essence — and is currently developing a TV series inspired by his first memoir of essays.

Michael’s latest book, “I Finally Bought Some Jordans” (out March 12), is a profoundly felt coda to his “I” trilogy, which began in 2018 with “I Can’t Date Jesus,” a New York Times bestseller, and was followed by “I Don’t Want to Die Poor” in 2020, an essay collection about debt and shame. “Jordans” is a noticeable detour from those previous offerings — its centerpiece is grief.

Through a series of serpentine encounters, touring from New York City to Houston to L.A., with the COVID-19 pandemic as its backdrop, the book addresses millennial angst and its many challenges. Throughout, Michael prevails as his characteristically funny self, scrutinizing au courant artwork (on “Slave Play”: “It makes you think. Much of what I thought throughout the play was, What the f—?”) while learning to find joy in middle age and local Tex-Mex delicacies, like the crab nachos from Cyclone Anaya’s, a beloved Houston eatery.

Still, the reality of what he’s weathered can’t be avoided. “Grief is just a really uncomfortable subject.” He tells me he didn’t want to avoid it. That he couldn’t. That he had to write about it. Write through it. So that’s exactly what he did.

Jason Parham: Prepping for the interview I realized it’s been 20 years, this year, that we’ve known each other.

Michael Arceneaux: It has.

JP: I’ve always admired how gracious you are when greeting folks. So I’d like to begin where you always begin with me. How are you?

MA: I’m actually having a really difficult time. Last year was the worst year of my life. I’m really deep in grief. But I have no choice but to pull it together to an extent because I don’t want this [book] to fail. And I don’t want to fail.

Arceneaux’s latest book, “I Finally Bought Some Jordans” (out March 12), is a profoundly felt coda to his “I” trilogy. Arceneaux wears Louis Vuitton shirt, trousers, jacket.

(Gabriel S. Lopez/For The Times)

JP: I wouldn’t call three books a failure.

MA: No. But I always worried about how Zora Neale Hurston died poor. If not for Alice Walker, literally all of her work would be lost. And that’s the case for a lot of Black writers and creatives. Not to be overly cynical — and this was something I told my mom because it was how I felt — I’m like, ‘I would probably be more valuable dead than alive.’ In my mind I already know how that goes, and it’s very true of a lot of people.

JP: Too many people.

MA: The point of the book is, I thought I would be in a certain place. I’ve made some strides that I’m happy with, but it’s not exactly what I thought it would be. And a lot of that stuff is beyond my control. That’s always been the case. It’s about accepting that. I’m very self-critical, and while I don’t want to value my work solely by monetary meaning, it’s hard to ignore that no matter how successful you’ve been or appear to be.

It’s a hard time to be a creative. There’s a real devaluing of what I do for a living. It’s unsettling. The [Hollywood writers] strike was really painful. Last year, like a lot of people, I felt it. It didn’t matter what level you were at — especially if you were Black. The discomfort is a wake-up call.

JP: It’s so different from when we started. You created a blog in 2005, the Cynical Ones. Are you nostalgic at all for that time in media?

MA: I wouldn’t say nostalgic. Something I wrestle with is that my writing and my pursuits kept me away from my mom. Ultimately I have to find my way and see things through. I’m not the first person to say this, but I’m learning in grief that I am a different person after losing her. Part of that is rediscovering an actual love of writing. This is a roundabout way of saying maybe I should do a newsletter. Maybe it can be something I play with. Because I started a blog to find my voice and get better as a writer. Samantha Irby has told me to do one forever. She has one where she does Judge Mathis recaps.

JP: Wait, really?

MA: Yes, it’s hilarious. I highly recommend it. Clearly I have a lot of complaints, but I still want to enjoy this. I didn’t put so much work and effort into this to not enjoy it. So much of what my ambition was rooted in is now a reward that can’t be given. It’s become, ‘How can I continue to enjoy what I’m writing?’

JP: That’s important.

MA: I don’t say this arrogantly, but anybody that’s both Black and queer, being pioneering is exhausting. You’re constantly having to change people’s perceptions. And in this climate it’s harder than ever.

JP: Rarely is Black art allowed to just exist.

“I’m not the first person to say this, but I’m learning in grief that I am a different person after losing her.”

— Michael Arceneaux

MA: I get the critique about that. Unfortunately, we live in the world as is and not how we want it to be. But if you very much stick to your voice and commit to it, all of that will shine through. I always remember how hard it was to get “I Can’t Date Jesus” published because everything mirrors that process, in that people have very limited ideas of what they think queer means, what gay means, what Black means, how that presents, what that sounds like. I hear the dumbest things. The same things I heard in publishing I hear even worse in television, even if it’s delivered with a smile. I’m exhausted from dealing with people’s prejudice.

JP: Was writing always your path?

MA: I was pushed into freelancing. I’m disappointed more writers are being pushed into it because people who don’t know what they’re doing are running companies into the ground, and everybody else is left to deal with it. A lot of the lamenting I’ve seen for media this year, I didn’t see that for all the Black media that was decimated a decade ago. And it doesn’t make what’s going on now any less awful, but it’s been an obvious problem for a while.

JP: You wrestle with that sentiment quite beautifully in the book, the difficulty in shouldering collective grief — what’s happening in the world — alongside private grief.

MA: I was very adamant during the promotion of my first book — because I felt it already happening — about not being boxed in. I didn’t want to be that sad gay person. I didn’t want to perpetuate certain tropes. Not that I carry that burden but it was in the back of my mind. That said, initially I had an idea of what I wanted the most recent book to be when I had a different title. Then life happened. It forced me to be more honest about how I felt, even about things I thought were settled. Clearly a block was there.

When I told my mom about the book, she said, ‘You’re angry.’ I didn’t think so, but I did recognize that there were unresolved feelings from my childhood. Now it’s become about accepting that some things won’t change. You won’t necessarily get that happy ending. I intended for this trio of books to end on a brighter note as I enter middle age, but life doesn’t work that way. Look at what’s happening around us.

JP: But I think the book is more relatable that way. More human. Life takes a curve; sure, it’s not what you expected, but you do your best to find hope and humor in the darkness. And maybe that hope takes the form of a haircut. You write about how getting a cut was a small way of regaining control. We’re the same in that we believe in the restorative power of a fade. There’s almost nothing that a fresh cut can’t fix, even if only momentarily.

“I was very adamant during the promotion of my first book — because I felt it already happening — about not being boxed in,” says Arceneaux. The writer stands outside the Hollyhock House, wearing Dior Men’s shirt and shoes, Zegna trousers, Canali coat.

(Gabriel S. Lopez/For The Times)

MA: There are people whose lives were destroyed when the plague happened and I want to acknowledge that. I worked really hard to make the first book happen. Going into the second book, it was about trying to get over life’s humps. Overall I was still fortunate that year. But I was struggling in the apartment I was in, in such a small space. I was alone. I’m not with my family. I don’t know what’s going on. I’d already experienced COVID, so I knew what it felt like.

The second book wasn’t the most important thing but I wanted it to reach people. I couldn’t do it at my best so I wanted something that I could have — and that was getting a cut up the street. It’s very vain and small, but other people were being much more selfish than I was. Catholic guilt is forever. A little bit of me was like, I’m triflin’ but not as triflin’. I wanted to feel like a bad bitch, and that’s the best I could get in such a dire situation.

JP: In one essay, you dig into the political elite — Barack Obama, Pete Buttigieg, Joe Biden, Eric Adams — and the limits of symbolism. How representation for the sake of representation doesn’t generate progress in the way some people seem to think, and how minorities bear the disproportionate brunt of their failures. November is around the corner. How f—ed are we?

MA: I don’t really believe in polling but I did see that even if Trump is convicted he is still within the margin of error. It’s an old man and a criminal. I’m trying to not be disparaging. They’re both old but Trump is crazy, and crazy presents a certain energy. I think we’re f—ed. A few convictions might actually complicate the situation. Still, I don’t know.

There’s this conversation happening on why Biden is not getting credit for the economy. But then half of Americans say they can’t afford to pay rent. And it’s grossly underreported. A lot of people are very discouraged.

JP: More than we probably even realize.

MA: People are not being spoken to. And there is this arrogance to [how Biden operates]. Like, he won’t apologize for his role in the massive death of Palestinians. It’s indecent in and of itself. But it’s not politically expedient. Now he’s prone to losing Michigan and Georgia, and it comes off like he doesn’t even care. They keep telling Black people to be grateful. The whole stimulus check thing, for example. They keep telling us we’re misinformed. It’s condescending to working-class Black people, who are the majority of us.

Black people have a right to be disappointed and not happy that this 80-year-old man has not done as much as he claims to do. Some people wanted to shut down the police altogether. He said no, no, no — rock this police bill. He said, ‘Democracy is so important.’ But they didn’t pass that voting rights bill. Maybe it would have failed either way, but he didn’t exert that much public pressure. Now we’re supposed to be guilted into it. Barack and Michelle are gonna come wagging their fingers and say, ‘Hit Pookie, tell him to vote.’ Pookie got every right to be disenchanted. Maybe it’s not articulated the best way, but people have a right to be disappointed. People are suffering and those $1200 checks meant a lot because it was the first time in their life where they felt like the government actually put money in their pocket. And if you can’t understand that on a basic level, you are screwed.

“I wanted to feel like a bad bitch, and that’s the best I could get in such a dire situation.”

— Michael Arceneaux

JP: Is there just less empathy these days?

MA: I think so. I mention in the book about a friend, Brian, who passed away from brain cancer. I started waking up in the middle of the night because my sleep pattern was off. I now realize that was my grief. A week ago I woke up and heard that Nicki Minaj diss record, “Big Foot.” There’s a line about Megan [Thee Stallion] lying on her dead momma. Then the memes started. That’s what I mean. There is a level of depravity now that is a lot more casual than it should be.

JP: There’s been a noticeable shift in the national mood for sure. Almost like one world is ending and another is beginning.

MA: I’ve joked in TV meetings that it could be illegal to be gay in a year [laughs]. I have that on my mind. Being from Texas, and what’s happening there, Texas is very much a template with what [Republicans] want to do with the rest of the country. So when people say, ‘How can you live in this multicultural society and still live in repression,’ I’m like, well look at Houston, the most ethnically diverse city in the country.

JP: Things feel noticeably scarier than 2016.

MA: It does. Especially because of my skin and I hate slavery [laughs]. My only hope is that Trump is crazy and who knows what he will say. Crazy is not very reliable.

“I’m learning in grief that I am a different person,” says Arceneaux. “Part of that is rediscovering an actual love of writing.”

(Gabriel S. Lopez/For The Times)

Producer: Ashley Woeber

Grooming: Arielle Park

Photo Assistant: Alma Lucia

Styling Assistant: Ryan Phung

Location: Hollyhock House

Jason Parham is a senior writer at Wired and a regular contributor to Image.

Lifestyle

Internal memo details cosmetic changes and facility repairs to Kennedy Center

A person walks a dog in front of the Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C., on Jan. 10, 2026.

Mandel Ngan/AFP via Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Mandel Ngan/AFP via Getty Images

An internal email obtained by NPR details some of the projected refurbishments planned for the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts. The renovations are more modest in scale and scope than what President Trump has publicly outlined for the revamped arts center, and it is unclear whether or not these plans are the extent of the intended renovations.

The email was sent on Feb. 2 by Brooks Boeke, the director of the Friends of the Kennedy Center volunteer program, to tour leaders and some staffers at the arts complex. In a response to NPR emailed Tuesday, Roma Daravi, the Kennedy Center’s vice president of public relations, wrote: “The Trump Kennedy Center has been completely transparent about the renovations needed to restore and revitalize the institution, ever since these proposals were unveiled for Congressional approval last summer. The changes that the Center will undergo as part of this intensive beautification and restoration project are critical to saving the building, enhancing the patron experience and transforming America’s cultural center into a world-class destination.”

The center’s closure was announced after many prominent artists canceled their planned appearances, saying that the Trump administration had politicized the arts. The Washington National Opera, which had been a resident organization at the Kennedy Center, left its home there last month, citing a “financially challenging relationship” under the center’s current leadership; The Washington Post, in an analysis of Kennedy Center ticket sales last October, reported that ticket sales had plummeted since Trump became the center’s chairman – even before the complex’s board renamed the venue as the Trump-Kennedy Center in December.

In her memo, Boeke cited Carissa Faroughi, the Kennedy Center’s director of the program management office. Boeke said that upcoming renovations to the complex’s Concert Hall will include replacing seating and installing marble armrests, which President Trump touted on his Truth Social platform in December as “unlike anything ever done or seen before!” Other changes include new carpeting, replacement of the wood flooring on the Concert Hall stage and “strategic painting.”

The planned changes to the Grand Foyer, Hall of States and Hall of Nations include a change of color scheme, from the current red carpeting and seating to “black with a gold pattern.” The carpeting and furnishings in these three areas and its electrical outlets were redone just two years ago, according to the Kennedy Center, and were accomplished without interrupting performances and programming.

Other planned work on the complex include upgrades of the HVAC, safety and electrical systems as well as improving parking. It is unclear whether these plans are the extent of the intended renovations; Daravi declined to answer that specific question.

The scope of the project as outlined in the memo differs sharply from public statements by President Trump, who said earlier this month on social media and in exchanges with the press that he intends a “complete rebuilding” and large-scale changes to the Kennedy Center, and that the arts complex is “dilapidated” and “dangerous” in its current state.

Earlier this month, Trump said that a two-year shutdown of the Kennedy Center is necessary to execute these renovations. This idea was echoed by the center’s president, Richard Grenell. Grenell wrote on X that the Kennedy Center “desperately needs this renovation and temporarily closing the Center just makes sense – it will enable us to better invest our resources, think bigger and make the historic renovations more comprehensive.”

On Feb. 1, Trump announced his plans to close the center entirely for two years “for Construction, Revitalization, and Complete Rebuilding” to create what he said “can be, without question, the finest Performing Arts Facility of its kind, anywhere in the World.” He later said that the project would cost around $200 million. The announcement came after many prominent artists had canceled their existing scheduled appearances at the Kennedy Center.

Lifestyle

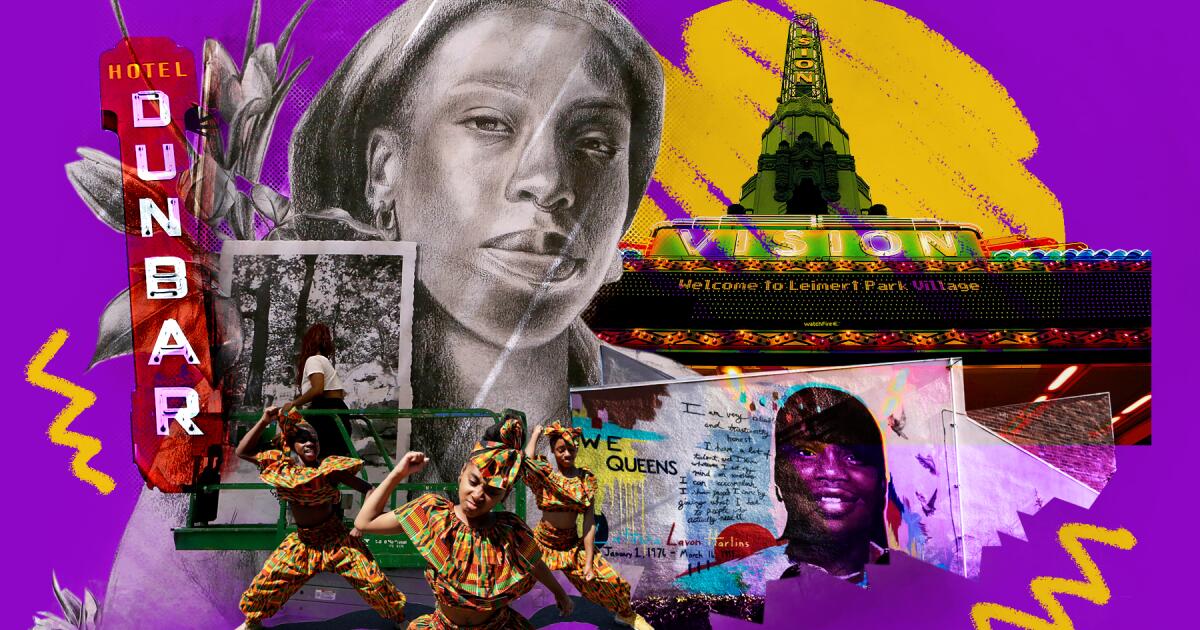

South L.A. just became a Black cultural district. So where should its monument stand?

For more than a century, South Los Angeles has been an anchor for Black art, activism and commerce — from the 1920s when Central Avenue was the epicenter of the West Coast jazz scene to recent years as artists and entrepreneurs reinvigorate the area with new developments such as Destination Crenshaw.

Now, the region’s legacy is receiving formal recognition as a Black cultural district, a landmark move that aims to preserve South L.A.’s rich history and stimulate economic growth. State Sen. Lola Smallwood-Cuevas (D-Los Angeles), who led the effort, helped secure $5.5 million in state funding to support the project, and in December the state agency California Arts Council voted unanimously to approve the designation. The district, formally known as the Historic South Los Angeles Black Cultural District, is now one of 24 state-designated cultural districts, which also includes the newly added Black Arts Movement and Business District in Oakland.

Prior to this vote, there were no state designations that recognized the Black community — a realization that made Smallwood-Cuevas jump into action.

“It was very frustrating for me to learn that Black culture was not included,” said Smallwood-Cuevas, who represents South L.A. Other cultural districts include L.A.’s Little Tokyo and San Diego’s Barrio Logan Cultural District, which is rooted in Chicano history. Given all of the economic and cultural contributions that South L.A. has made over the years through events like the Leimert Park and Central Avenue jazz festivals and beloved businesses like Dulan’s on Crenshaw and the Lula Washington Dance Theatre, Smallwood-Cuevas believed the community deserved to be recognized. She worked on this project alongside LA Commons, a nonprofit devoted to community-arts programs.

Beyond mere recognition, Smallwood-Cuevas said the designation serves as “an anti-displacement strategy,” especially as the demographics of South L.A. continue to change.

“Black people have experienced quite a level of erasure in South L.A.,” added Karen Mack, founder and executive director of LA Commons. “A lot of people can’t afford to live in areas that were once populated by us, so to really affirm our history, to affirm that we matter in the story of Los Angeles, I think is important.”

The Historic South L.A. Black Cultural District spans roughly 25 square miles, situated between Adams Boulevard to the north, Manchester Boulevard to the south, Central Avenue to the east and La Brea Avenue to the west.

Now that the designation has been approved, Smallwood-Cuevas and LA Commons have turned their attention to the monument — the physical landmark that will serve as the district’s entrance or focal point — trying to determine whether it should be a gateway, bridge, sculpture or something else.

And then there’s the bigger question: Where should it be placed? After meeting with organizations like the Black Planners of Los Angeles and community leaders, they’ve narrowed their search down to eight potential locations including Exposition Park, Central Avenue and Leimert Park, which received the most votes in a recent public poll that closed earlier this month.

As organizers work to finalize the location for the cultural district’s monument by this summer, we’ve broken down the potential sites and have highlighted their historical relevance. (Please note: Although some of the sites are described as specific intersections, such as Jefferson and Crenshaw boulevards, organizers think of them more as general areas.)

Lifestyle

Urban sketchers find the sublime in the city block

Portland’s Union Station, captured in watercolor and pen by an artist at the Urban Sketchers Portland event.

Deena Prichep

hide caption

toggle caption

Deena Prichep

Great landscape art can take you into a world: the majestic hills of Georgia O’Keeffe’s Southwestern sublime; the pastoral calm of Monet’s water lilies. But for years now, groups of amateurs have been gathering with sketchbooks in cities across the world to turn their artistic gaze to the everyday sights of skyscrapers and sidewalks — and find beauty there.

The idea of “urban sketchers,” or the name at least, started almost 20 years ago. Gabriel Campanario was looking to get to know his new home — and improve his drawing skills.

“We had just moved to Seattle, and I started drawing. Like every day I drew the commuters on the bus, I would draw the mountains, the buildings,” remembered Campanario.

He posted his drawings on the website Flickr and invited other artists to join the online group, which led to in-person groups. And then more chapters, and then international gatherings. Urban Sketchers now reports more than 500 chapters in over 70 countries.

“You can go to another town and meet up with a Sketchers group there,” said Campanario. “And you may not speak the language, but they all can look at your sketchbook and somewhat relate.”

Urban Sketchers Portland was one of the earliest chapters. They meet up monthly. Amy Stewart is one of the organizers.

“We’ll just pick a different neighborhood to explore, where we might be drawing old houses, or little corner markets, or maybe there’s a cool old movie theater to draw,” said Stewart.

Stewart is a writer by profession and says a lot of the sketchers who show up (usually about 50 or so) are similarly amateurs, along with a few more-experienced artists.

Karen Hansen, who discovered Urban Sketchers last year, came prepared with a folding chair and a magnetic watercolor paint palette, so she could pop in the colors she wanted to use for today’s painting.

Deena Prichep

hide caption

toggle caption

Deena Prichep

At a recent meetup at Portland’s Union Station, self-described recovering architect Bob Boileau appreciated that after a career spent drawing straight lines, “It’s nice to just get some squiggly in there and, and put some color and draw how I feel.”

Others, like sketcher Karen Hansen, noted that stopping and really paying attention to a scene helped her see the details that she had taken for granted in everyday life.

“When you’re drawing and painting something, you’re really looking at the shapes and the shadows and the textures,” said Hansen.

At the Portland meetup, sketchers were gathered in little clusters around the train station, capturing its red bricks and tall clock tower with watercolors, or pen and ink, or colored pencils.

It’s arguably not as majestic as most rural landscapes, but Noor Alkurd, drawing at his second Urban Sketchers meetup, said that the boxes and lines of cities are great for beginning artists. And besides, landscapes are overrated.

Urban Sketchers events end with a “throwdown,” where all the artists lay out their sketchbooks and share their work with each other.

Deena Prichep

hide caption

toggle caption

Deena Prichep

“I mean, come on — cityscapes are so fun!” Alkurd said with a laugh. “I think drawing has helped me just see more of everyday life. It kind of helps you train your own eye for what you find beautiful.”

At the end of the sketch session, all of the participants laid their finished art side by side to compare and admire.

There was some shop talk among sketchers about technique and materials, and some recognition of progress for sketchers who had been coming for a while. But mostly, sketchers said it’s just a chance to create a record of a moment, to take in other perspectives, and to notice a little bit more about the city they see every day.

-

Oklahoma2 days ago

Oklahoma2 days agoWildfires rage in Oklahoma as thousands urged to evacuate a small city

-

Science1 week ago

Science1 week agoA SoCal beetle that poses as an ant may have answered a key question about evolution

-

Health1 week ago

Health1 week agoJames Van Der Beek shared colorectal cancer warning sign months before his death

-

Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoHP ZBook Ultra G1a review: a business-class workstation that’s got game

-

![“Redux Redux”: A Mind-Blowing Multiverse Movie That Will Make You Believe in Cinema Again [Review] “Redux Redux”: A Mind-Blowing Multiverse Movie That Will Make You Believe in Cinema Again [Review]](https://i1.wp.com/www.thathashtagshow.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/Redux-Redux-Review.png?w=400&resize=400,240&ssl=1)

![“Redux Redux”: A Mind-Blowing Multiverse Movie That Will Make You Believe in Cinema Again [Review] “Redux Redux”: A Mind-Blowing Multiverse Movie That Will Make You Believe in Cinema Again [Review]](https://i1.wp.com/www.thathashtagshow.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/Redux-Redux-Review.png?w=80&resize=80,80&ssl=1) Movie Reviews1 week ago

Movie Reviews1 week ago“Redux Redux”: A Mind-Blowing Multiverse Movie That Will Make You Believe in Cinema Again [Review]

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoCulver City, a crime haven? Bondi’s jab falls flat with locals

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoTim Walz demands federal government ‘pay for what they broke’ after Homan announces Minnesota drawdown

-

Fitness1 week ago

Fitness1 week ago‘I Keep Myself Very Fit’: Rod Stewart’s Age-Defying Exercise Routine at 81