Lifestyle

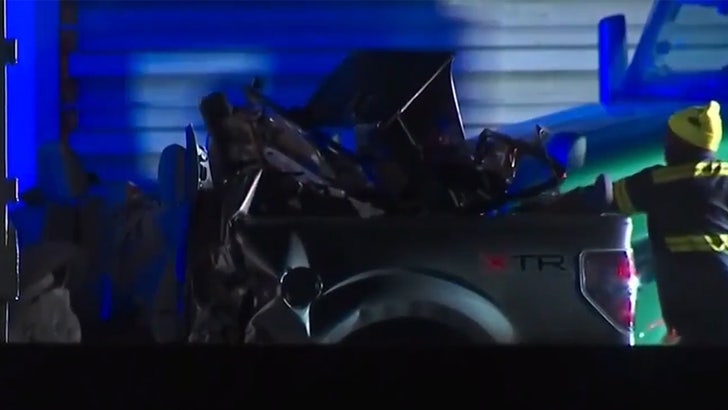

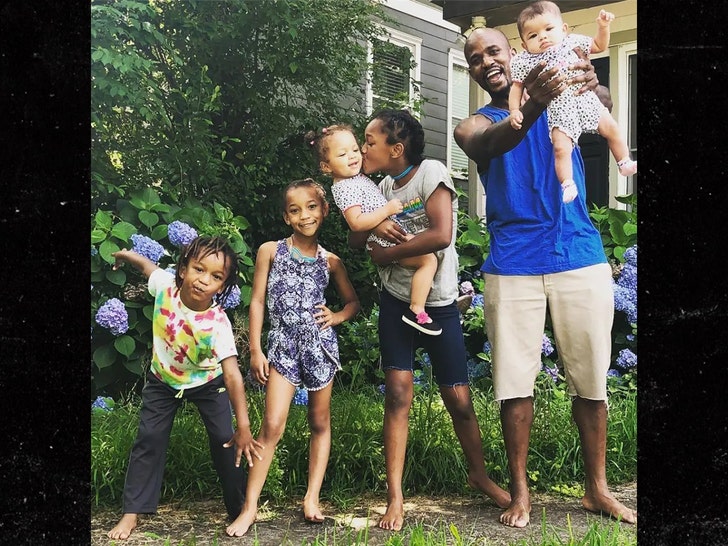

‘Black Panther’ Stuntman Was Trick or Treating with Family Before Fatal Crash

The “Black Panther” stuntman who was killed in a car crash last week had just wrapped up a night of Halloween fun before the fatal wreck … TMZ has learned.

Taraja Ramsess‘ mother, Akili, tells us her son was in the car with 6 others that fateful night — including his ex-wife, Selena, and a mix of 5 children … most of whom he’d had with her, and a newborn he shares with his current partner, Lisa, who was at home.

Anyway, we’re told Taraja and Selena had just finished taking all the children trick or treating in the Atlanta area and were on their way home when they got in the accident.

As we reported … Taraja died at the scene, as did two of his daughters — a 13-year-old and an 8-week-old little girl. His 10-year-old son later died after being taken off life support.

FOX 5

Selena and two daughters she shared with Taraja survived — they all suffered non-life-threatening injuries, although one of the daughters is still in the hospital. In terms of how Akili heard the tragic news … she tells us Selena called and was inconsolable.

Akili says it was the worst night of her life, and the heartache of losing her son and grandchildren was compounded by not immediately knowing who was alive and dead.

Apparently, first responders had taken everybody to different hospitals, and it created a confusing/chaotic situation to try and track down everyone in the aftermath. Akili adds, “It’s impacted our family. It’s now part of us — our family needs some time to heal and recover and go on with our lives best we can.”

Obviously, the entire family is distraught in the wake of all this … and we’re told everybody is trying to cope as best they can in the wake of such an awful catastrophe that claimed so many lives.

Now, in terms of what exactly caused the crash — remember, Taraja slammed into a tractor-trailer while coming off the freeway — Akili isn’t ready to discuss it. It’s under investigation.

Lifestyle

Why bananas may become one of the first casualties of the dockworkers strike

Most bananas imported to the U.S. come through ports affected by the dockworkers’ strike. And the fruit’s limited shelf life made it hard to stockpile in advance.

Jewel Samad/AFP/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Jewel Samad/AFP/Getty Images

If you enjoy sliced bananas with your cereal or drinking a banana smoothie, you might want to savor it while you can. Fresh bananas could be one of the first casualties of the dockworkers’ strike.

The strike, now in its third day, has halted traffic at ports along the east coast and the gulf coast which handle an estimated three-quarters of all banana imports.

That includes the port of Wilmington, Del., which is the number one gateway for bananas coming into the U.S.

Ships from Dole and Chiquita — two of the world’s biggest banana producers — ferry more than 1.5 million tons of bananas to Wilmington every year from Central and South America.

Many of those bananas are then trucked to M. Levin & Co. in Philadelphia — which has been trading bananas in the region for four generations.

“The bananas are on the water for about seven days,” says Tracie Levin, who helps to oversee daily operations at the firm. “They come through the ports here. We pick them up. We ripen them in the ripening rooms for a few days, and then they go out to their stores and that’s how they get to consumers in the area.”

M. Levin & Company typically handles about 35,000 cartons of bananas in its Philadelphia ripening rooms every week. The wholesaler supplies big box stores and corner markets as far west as Chicago.

courtesy M. Levin & Co.

hide caption

toggle caption

courtesy M. Levin & Co.

That normally smooth and largely invisible process is one of many that have been interrupted by the dockworkers’ strike, which has halted shipments of everything from auto parts to wine.

Levin is hoping for a quick resolution.

“We want a fair deal for everyone, from the ports to the workers,” she says. “Our country relies very heavily on our ports so this is definitely going to have a ripple-down effect if it doesn’t come to an end soon.”

In the banana business for over a century

Of all the goods now treading water in shipping containers, few are more sensitive to the passage of time than fresh fruit. Auto parts and wine generally don’t spoil if they’re stuck in transit for a little while. But for bananas, the clock is ticking.

“These bananas do have a shelf life, even when they’re sitting in the refrigerated containers,” Levin says. “If they sit too long they will dry out. They will not ripen properly. It’s really important that they get unloaded before they end up sitting out there too long and just become trash.”

Tracie Levin’s great-grandfather began ripening bananas on Dock Street in Philadelphia in 1906. One of his original wagons is still on display in the company’s warehouse.

courtesy M. Levin & Co.

hide caption

toggle caption

courtesy M. Levin & Co.

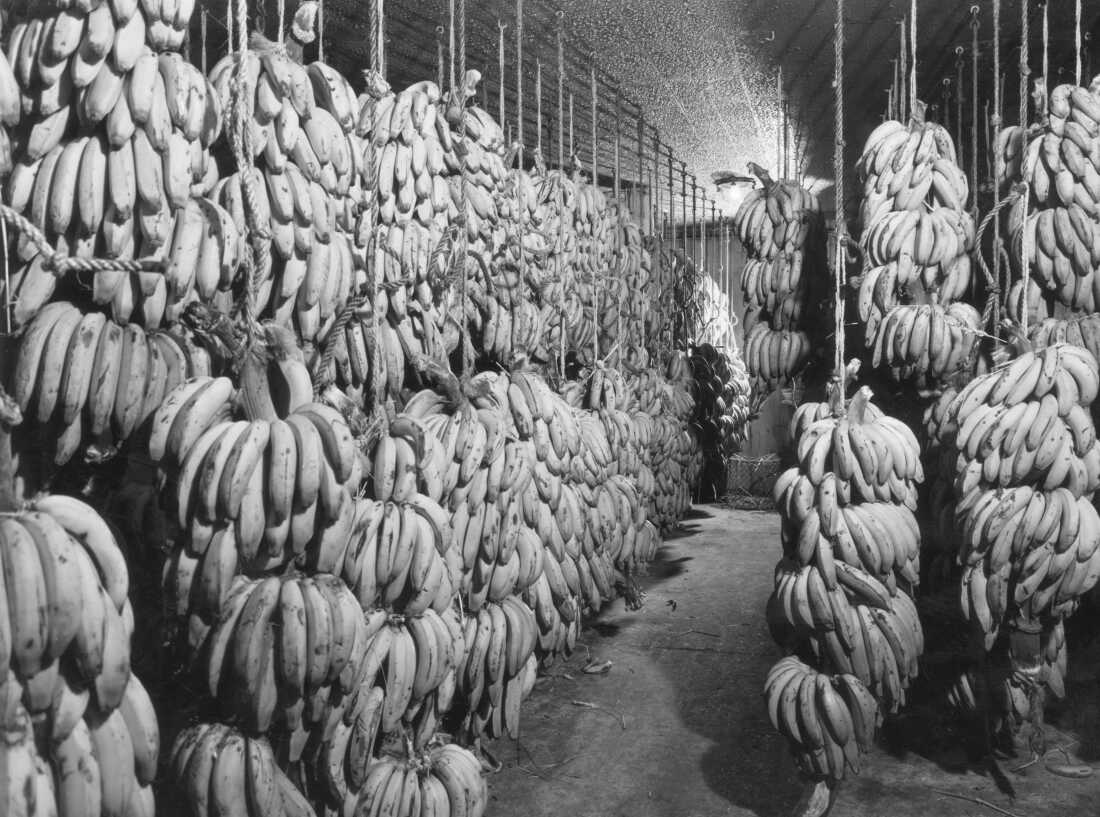

It’s something Levin knows very well, since her family has been in the banana business for over a century.

“My great-grandfather in 1906 started ripening bananas on Dock Street in Philadelphia in the cellar,” she says.

In those early days, bananas arrived by the boatload still attached to giant stalks. Today the fruit comes in cardboard boxes, stacked in refrigerated shipping containers. Levin’s company handles about 35,000 of those 40-pound cartons every week, supplying big box stores and corner retailers as far west as Chicago.

Bananas are ripening in a warehouse in Kingston-upon-Thames, England, on February 1954.

Fox Photos/Getty Images/Hulton Archive

hide caption

toggle caption

Fox Photos/Getty Images/Hulton Archive

People may soon go bananas

Levin’s company stockpiled extra truckloads of green bananas before the strike, and they do have some ability to slow the ripening process — but only for so long.

The wholesaler has enough fruit on hand to last a week or so, but after that, look out.

“Our banana supply will be dwindling if the ships aren’t getting the fruit off,” Levin says. “The consumer may see a banana shortage at their local grocery stores very soon.”

For now, grocery shoppers might want to pick up a few extra bananas, just in case. But of course, those won’t stay fresh long either.

Lifestyle

Championing Retail Career Development at Aesop

Lifestyle

This horror genre is scary as folk – and perfect October viewing

In 1973’s The Wicker Man, British policeman (Edward Woodward) visits a remote Scottish island to find that the locals have embraced a form of paganism.

Archive Photos/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Archive Photos/Getty Images

It’s October. Some of your neighbors will spend this, the official first weekend of spooky season, going all-out with inflatable yard skeletons and ghosts. They will embark upon the annual attempt to make candy corn, aka high-fructose ear wax, a thing. They’ll adorn their front porches with those cotton spider webs that look nothing like real spider webs and instead just make it look like they went and ritually murdered a white sweater so they could hang its dismembered corpse across their doorway as a grisly warning to all other knitwear.

For me, it’s a more simple, elemental formula: Hot cider, cider donuts, folk horror.

The appeal of cider and donuts is universal, but folk horror might need some defining. Essentially, it’s horror set in remote, isolated areas where nature still holds sway. Well, nature paired with the superstitious beliefs of the locals, who tend to treat unwary outsiders with suspicion (if the outsiders are lucky) or malice (if they’re not).

The classic example is 1973’s The Wicker Man, in which an uptight, devout, and veddy veddy British policeman (Edward Woodward) visits a remote Scottish island to investigate the disappearance of a young girl. Turns out the locals have embraced a form of Celtic paganism, which doesn’t sit right with him. He says as much to the island’s aristocratic leader, a mysterious and charismatic sort played by Christopher Lee. Things don’t end well for our poor British bobby – though presumably the island will enjoy a bountiful harvest, so, you know: Big picture, it’s still a win.

Other founding classics of the genre include 1968’s The Witchfinder General and 1971’s The Blood on Satan’s Claw, which of the three films has the least going for it, apart from its title, which is, all reasonable people can agree, metal AF.

I love me some folk horror, and am never happier than when I can while away a damp, foggy (and thus obligingly atmospheric) October afternoon mainlining new and old examples of the form like Kill List, You Won’t Be Alone, Viy, The Ritual, Häxan, The Medium, Apostle, Midsommar, The Witch, Hereditary, Night of the Demon, A Field in England, Robin Redbreast, and Men. (Looking for more examples? Check out the documentary Woodlands Dark and Days Bewitched: A History of Folk Horror.)

Florence Pugh in Midsommar.

Gabor Kotschy/A24

hide caption

toggle caption

Gabor Kotschy/A24

Some folk horror involves supernatural elements, but I confess a particular fondness for those stories that don’t – stories where it’s the folk themselves (read: the locals, and their beliefs) who are the true and only source of the horror. (I won’t spoil which of the above films traffic in human vs. supernatural evil, in case you haven’t seen them.)

Talismans and turtlenecks

The Wicker Man was the first folk horror film I saw as a kid, which is maybe why I harbor a deep love of folk horror set in ’70s Britain, a time and place when an interest in the occult became faddish, inspiring a wave of folk horror specifically inflected with Satanic panic. Many of these films were set in the past, but those like The Wicker Man were set in the then-present, a time when men wore wavy hair and tight bell bottoms. Christopher Lee’s Lord Summerisle, for example, sported a kicky tweed leisure suit topped off by a burnt-orange sweater.

It’s why I think of this very specific subgenre of ‘70s folk horror as Talismans and Turtlenecks.

I just came across a new-to-me example of T & T last Sunday afternoon, which was suitably cold and wet and misty: 1970’s The Dunwich Horror. A stiff-haired Sandra Dee, desperately attempting to shake her goody-goody image, plays a woman who falls under the sway of a young and hilariously intense, wide-eyed Dean Stockwell. (Seriously, you keep waiting for his character to blink, but instead he just keeps goggling fixedly at the world around him. At one point he makes a pot of tea, staring at it so fiercely through every stage of the process you start to wonder if he’s trying to convince it to hop into bed with him.)

Don’t get me wrong: It’s a cheesy film, filled with crummy dialogue and hammy acting and cheap sets and one fight scene so wildly inept that has to be seen to be disbelieved. I won’t reveal if the threat hanging over the film is human or supernatural (though the fact that it’s based on an H.P. Lovecraft short story should tip you off). But I will say that Stockwell sports a thick, curly hairdo, a cravat, two count-em two pinky rings, and a huge mustache that curls under itself at either end, in the process effectively turning my guy’s mouth into a parenthetical statement.

You can watch it for free, with commercials, on Pluto TV, which I swear is a real streaming service and not something I made up. The Dunwich Horror is not remotely scary, but it does have something to say, I suppose, about the madness of crowds and what, back in grad school, we used to call “othering.” (The Stockwell character is the scion of an eccentric family that the local community has shunned for generations, you see.)

And that, of course, is the abiding appeal of folk horror: It takes those universal feelings of alienation and isolation that make us all feel like outsiders in our own communities and gives them flesh. When the supernatural is involved, sometimes that flesh pulses and oozes. Sometimes it’s furry and clawed.

But whenever the story is about our collective tendency to cling to belief in the supernatural, the flesh involved is all too human, and probably gets stabbed with a sacrificial dagger in the final reel. Happy spooky season, y’all.

This piece also appeared in NPR’s Pop Culture Happy Hour newsletter. Sign up for the newsletter so you don’t miss the next one, plus get weekly recommendations about what’s making us happy.

Listen to Pop Culture Happy Hour on Apple Podcasts and Spotify.

-

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25439572/VRG_TEC_Textless.jpg)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25439572/VRG_TEC_Textless.jpg) Technology4 days ago

Technology4 days agoCharter will offer Peacock for free with some cable subscriptions next year

-

World3 days ago

World3 days agoUkrainian stronghold Vuhledar falls to Russian offensive after two years of bombardment

-

World3 days ago

World3 days agoWikiLeaks’ Julian Assange says he pleaded ‘guilty to journalism’ in order to be freed

-

Technology2 days ago

Technology2 days agoBeware of fraudsters posing as government officials trying to steal your cash

-

Virginia4 days ago

Virginia4 days agoStatus for Daniels and Green still uncertain for this week against Virginia Tech; Reuben done for season

-

Sports1 day ago

Sports1 day agoFreddie Freeman says his ankle sprain is worst injury he's ever tried to play through

-

Health19 hours ago

Health19 hours agoHealth, happiness and helping others are vital parts of free and responsible society, Founding Fathers taught

-

News20 hours ago

News20 hours agoLebanon says 50 medics killed in past three days as Israel extends its bombardment