Lifestyle

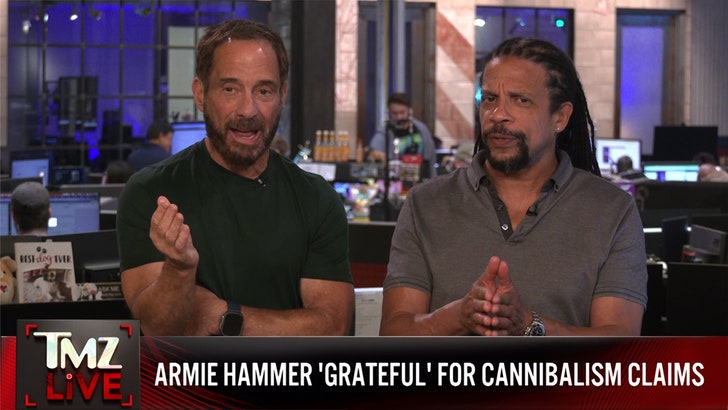

Armie Hammer Says He's Selling His Truck, Can't Afford Gas Guzzler

Instagram / @armiehammer

Armie Hammer says he’s starting fresh now that he’s back in Los Angeles … and that means parting ways with a gas-guzzling truck full of happy family memories.

The actor says he’s having to sell a truck he’s owned for 7 years because the cost to fill up his tank is out of control … taking it to CarMax even though his kids are begging him not to kiss goodbye to the car.

Armie’s cleaning out the car before finalizing the deal, and he’s getting emotional thinking back on all the family road trips and milestones he went through behind the wheel … including taking his kids home from the hospital.

AH says his kids want him to hang on to the truck, but with gas well over $4 a gallon in L.A. and all the traffic and city driving, Armie says it’s just not practical for him anymore.

Instead, Armie says he’s downsizing to small hybrid car … and he says he keeps reminding himself of all the money he’s going to save on gas and how much easier parking is going to be as a way to cope with the loss of his beloved truck.

TMZ.com

Armie says he bought the ride back in 2017 as a Christmas gift to himself … and it’s pretty clear in the video how much the car means to him and his kids.

Tough pill to swallow here for Armie on the eve of his birthday … but he says he’s got no choice but to start fresh with a new car, apartment, and life.

Lifestyle

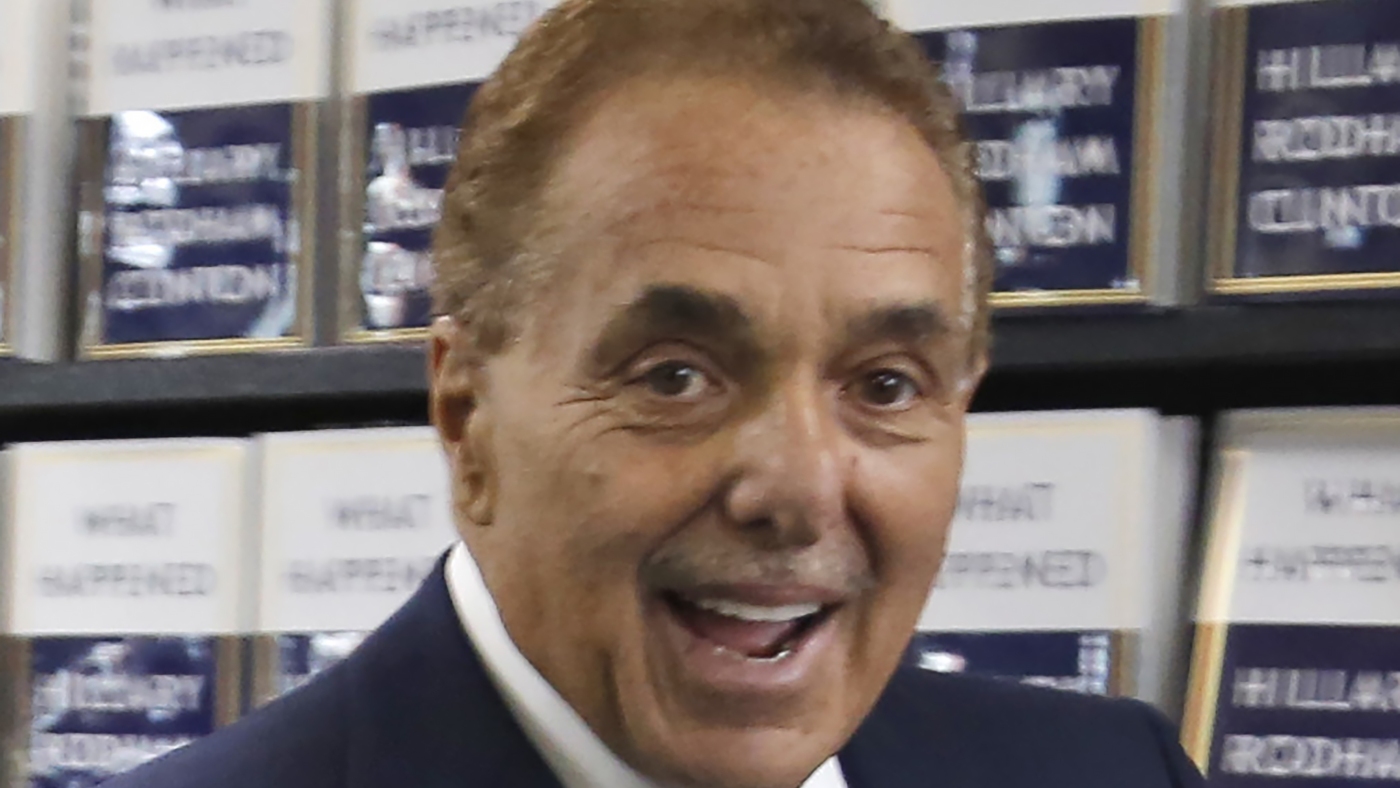

Leonard Riggio, who built Barnes & Noble into a bookselling empire, dies at 83

Leonard Riggio, then chairman of Barnes & Noble, arrives at a bookstore in New York on Sept. 12, 2017. Riggio died on Tuesday.

Seth Wenig/AP

hide caption

toggle caption

Seth Wenig/AP

NEW YORK — Leonard Riggio, a brash, self-styled underdog who transformed the publishing industry by building Barnes & Noble into the country’s most powerful bookseller before his company was overtaken by the rise of Amazon.com, has died at age 83.

Riggio died Tuesday “following a valiant battle with Alzheimer’s disease,” according to a statement issued by his family. He had stepped down as chairman in 2019 after the chain was sold to the hedge fund Elliott Advisors.

“His leadership spanned decades, during which he not only grew the company but also nurtured a culture of innovation and a love for reading,” reads a statement from Barnes & Noble.

Riggio’s near-half century reign began in 1971 when he used a $1.2 million loan to purchase Barnes & Noble’s name and the flagship store on lower Fifth Avenue in Manhattan. He acquired hundreds of new stores over the next 20 years and, in the 1990s, launched what became a nationwide empire of “superstores” that combined a chain’s discount prices and massive capacity with the cozy appeal of couches, reading chairs and cafes.

“Our bookstores were designed to be welcoming as opposed to intimidating,” Riggio told The New York Times in 2016. “These weren’t elitist places. You could go in, get a cup of coffee, sit down and read a book for as long as you like, use the restroom. These were innovations that we had that no one thought was possible.”

He grew up working class in New York City, liked to say he preferred socializing with childhood pals over fellow business leaders and was informal enough among associates to be known as “Lenny.” But in his time no one in the book world was more feared. With the power to make any given book a best seller, or a flop, to alter the market on an idle whim, Riggio could terrify publishers simply by suggesting prices were too high or that he might sign up such top sellers as Stephen King and John Grisham and publish them himself. He even tried to buy the country’s biggest book wholesaler, Ingram, in 1999, but backed off after facing government resistance.

By the end of the 1990s, an estimated one of every eight books sold in the U.S. were purchased through the chain, where front table displays were so valuable that publishers paid thousands of dollars to have their books included. Thousands of independent sellers went out of business even as Riggio insisted that he was expanding the market by opening up in neighborhoods without an existing store. Instead, independent owners spoke of being overwhelmed by competition from both Barnes & Noble and Borders Book Group, the rival chains sometimes setting up stores in close proximity to each other and to the locally owned business.

Barnes & Noble became so identified as an overdog that one of the 1990s’ most popular romantic comedies, “You’ve Got Mail,” starred Tom Hanks as an executive for the “Fox Books” chain and Meg Ryan as the owner of an endangered independent store in Manhattan.

“We are going to seduce them with our square footage, and our discounts, and our deep arm chairs, and our cappuccino,” Hanks’ character confidently declares. “They’re going to hate us at the beginning, but we’ll get ’em in the end.”

Acrimony from independent booksellers

For a time, it seemed industry conversation was an ongoing response to Barnes & Noble. Publishers were known to change the cover or title of a book simply because a Barnes & Noble official had objected. “Angela’s Ashes” author Frank McCourt found himself condemned by the American Booksellers Association, the trade organization for independents, after agreeing to appear in a Barnes & Noble commercial. On the floor of the industry’s annual national trade show, long hosted by the ABA, independent store employees would hiss at attendees wearing Barnes & Noble badges.

When novelist Russell Banks, addressing Barnes & Noble’s annual shareholder meeting in 1995, declared that he was both a stock holder and a happy B&N customer, some independent sellers stopped offering his books.

“You must know that I’ll never read, buy or sell another word you write,” Richard Howorth, owner of Square Books in Oxford, Mississippi, wrote to him. ”These are the kindest things I can think of to say to you.”

Tensions led to legal action when the ABA — on the eve of the 1994 convention — announced it was suing Barnes & Noble and five leading publishers for unfair trade practices. Some of the publishers were so angered they boycotted the gathering the following year and only returned after the ABA sold the show to Reed Exhibitions. In 1998, the ABA sued Barnes & Noble and Borders for unfair business practices (both cases were settled out of court).

The internet shifts bookselling

Riggio began the 2000s at the height of power, with more than 700 superstores and hundreds of others outlets. But internet commerce was growing quickly and Barnes & Noble, with its roots in physical retail, lacked the imagination and flexibility of the startup from Seattle that called itself “Earth’s Biggest Bookstore,” Amazon.com. The online giant launched in 1995 by Jeff Bezos gained business throughout the 2000s and by the early 2010s had displaced Barnes & Noble through such innovations as the Kindle e-book reader and the Amazon Prime subscription service.

Bezos would liken himself to David taking down Goliath, although the contrast between the leaders also had the feel of an Aesop’s fable: The muscular, mustachioed Riggio, a boxer’s son, upended by the quick and clever Bezos.

“We’re great booksellers; we know how to do that,’’ Riggio acknowledged to the Times in 2016. “We weren’t constituted to be a technology company.”

Barnes & Noble started its own online site in the late 1990s, but such initiatives as the Nook e-book reader and a self-publishing platform failed to stop Amazon. Not even the collapse of Borders after the 2008-2009 economic crisis mattered for Barnes & Noble, which after decades of expansion closed more than 100 stores between 2009 and 2019.

An unlikely ally of independent booksellers

By the time of Riggio’s retirement, independent sellers regarded the chain not as a threat, but as an ally in the fight against Amazon to keep physical stores alive. At the 2018 booksellers convention, Riggio and ABA CEO Oren Teicher, once enemies in business and in court, praised each other during a joint appearance.

“My standing here, doing what I’m about to do (introduce Riggio) would have been impossible to imagine several years ago,” Teicher said at the time. “The simple fact is that our business is stronger and American readers benefit when there is a vibrant and healthy network of brick-and-mortar bookshops all across the country.”

During the 2010s, Barnes & Noble seemed unleadable and unwanted. The board announced in 2010 that the company was for sale, but no one offered to buy it. Four CEOs left in five years and Barnes & Noble’s stock dropped 60% between 2015 and 2018. New rumors of a sale lasted for months before Elliott Advisors, which had previously purchased the British chain Waterstones, bought Barnes & Noble for $638 million and hired Waterstones chief executive James Daunt to lead B&N.

“I don’t miss being a business person, I had enough of that. But I do miss the bookselling part, helping to find books to recommend to customers,” Riggio told Publishers Weekly in 2021.

Riggio’s roots and early bookselling ventures

Bookselling and family often overlapped for Riggio. His brother Steve Riggio served for years as vice chairman of Barnes & Noble and another brother, Thomas Riggio, helped run a trucking company that shipped the store’s books. After being interviewed in 1974 by the trade publication College Store Executive, Leonard Riggio met for coffee with the editor, Louise Altavilla, who seven years later became his second wife (Riggio had three children, two with his first wife, one with his second).

Leonard S. Riggio was the eldest son of a prize fighter (who twice defeated Rocky Graziano) turned cab driver and a dress maker. Even in childhood, he advanced quickly, skipping two grades and attending one of the city’s top high schools, Brooklyn Tech. He studied metallurgical engineering at New York University’s night school before focusing on commerce, and by day absorbed the bookselling world and the rising cultural rebellion of the 1960s.

Working as a floor manager at the campus book store, he learned enough to drop out of school and start a rival shop in 1965 — SBX (Student Book Exchange), where he allowed student activists to use the copying machine to print copies of anti-war leaflets. SBX was so successful he bought several other campus stores and was in position by 1971 to buy Barnes & Noble and its single Manhattan store. A few years later, he became the rare bookseller to run television commercials, with the catchphrase “Barnes & Noble! Of Course! Of Course!”

Riggio and the independent community may have seemed to hold opposing values, but they shared a love of reading and the arts and a liberal political outlook. He was a generous philanthropist and a prominent supporter of Democratic politicians. He was even friendly with the consumer activist and presidential candidate Ralph Nader, who featured Riggio, Ted Turner and Yoko Ono among others in his 2009 novel “Only the Super-Rich Can Save Us!”, in which Nader imagines a progressive revolution from above.

“Ever since he was a boy from Brooklyn, he’d had a visceral reaction to the way workings stiffs and the poor were treated on a day-to-day basis,” Nader wrote of Riggio, who did at times stand apart from his management peers. When some 200 business leaders were questioned by Fortune magazine in the 1990s about their political ideas, only Riggio supported the raising of worker pay.

“Money can become a burden, like something you carry on your shoulders,” he told New York magazine in 1999. “My nature is to be a ball-buster, but my role is to help people.”

Lifestyle

Celebrating movie icons: Molly Ringwald

Ringwald represented teen angst in ’80s films like Sixteen Candles and The Breakfast Club. She’s also worked as a jazz musician, an author and a translator. Originally broadcast Feb. 12, 2024.

Hear The Original Interview

Lifestyle

How to tour a haunting Santa Barbara estate that's been frozen in time for half a century

The house, a French palace on a Santa Barbara bluff, stands as undisturbed as a crime scene, a pair of unstrung harps in the music room, china laid out on the dinner table, waves crashing on East Beach below.

This is the mansion that heiress Huguette Clark left behind — well, one of them. For half a century, as Clark (1906-2011) paid an estimated $40,000 per month to keep it unchanged, the coveted estate known as Bellosguardo remained no livelier than the cemetery next door.

A tour group waits to enter Santa Barbara’s Bellosguardo Estate. (Christopher Reynolds / Los Angeles Times)

But now outsiders trickle in. For the last year and a half, the Bellosguardo Foundation has been quietly offering ground-floor tours for $100 a head, and it may soon open up more of the long-idle estate to visitors.

For anyone fascinated by great estates, robber barons, generational wealth or just human psychology, the tour is a chance to see territory that’s been off-limits for decades. It’s also a haunting illustration of what money can buy and what it can’t.

“We used to come to the cemetery and peek over the wall,” confessed Patti Gibbs, a longtime Santa Barbara resident who was among those on hand for the 10 a.m. tour one recent Wednesday.

“I’ve been waiting for them to let me in since I read the book years ago,” said visitor Peggy Simmons of Ojai.

The book she mentioned is “Empty Mansions,” by Bill Dedman and Paul Clark Newell Jr., which lays out the history of the Clarks and their homes in California, New York and Connecticut.

But stepping into the story is different from reading it. With docents Susan Bush and Cindy McClelland leading the way, Gibbs, Simmons and a handful of other visitors entered the front door.

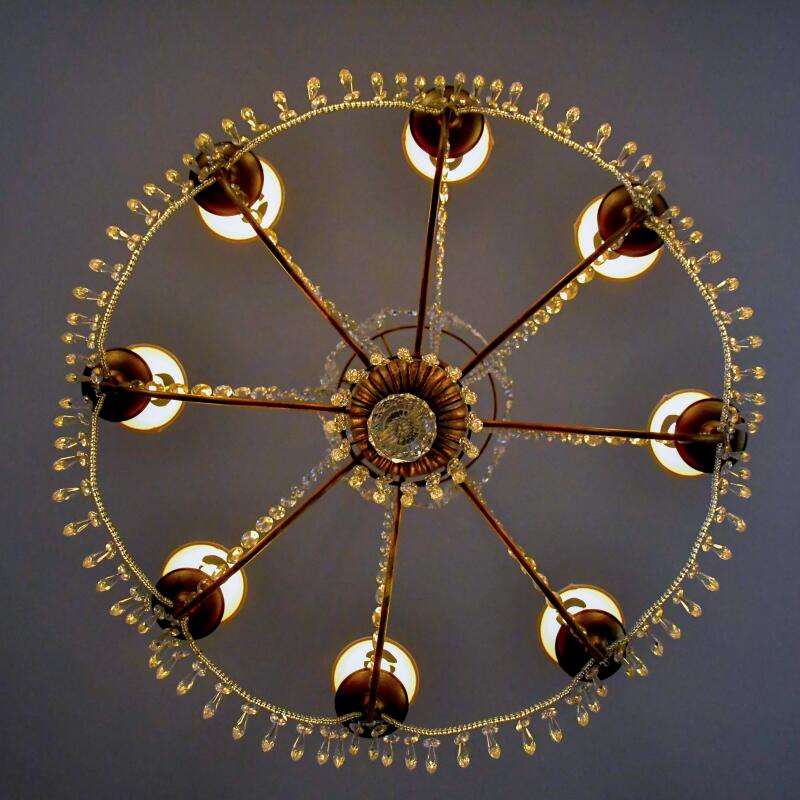

The dining room, set with dinnerware. One of many custom chandeliers — this one hangs in the mansion’s art studio. A portrait in the estate shows heiress Huguette Clark, who died in 2011 at age 104. (Christopher Reynolds / Los Angeles Times)

The music room of the estate.

(Christopher Reynolds / Los Angeles Times)

They examined the telephone room to the left, then the coat room to the right (with a portrait of a French World War I hero on the wall) and the Steinway piano at the foot of the spiral staircase. And they listened closely as the docents addressed the morning’s central questions:

Where did the money come from? And why did Huguette Clark put the mansion on pause?

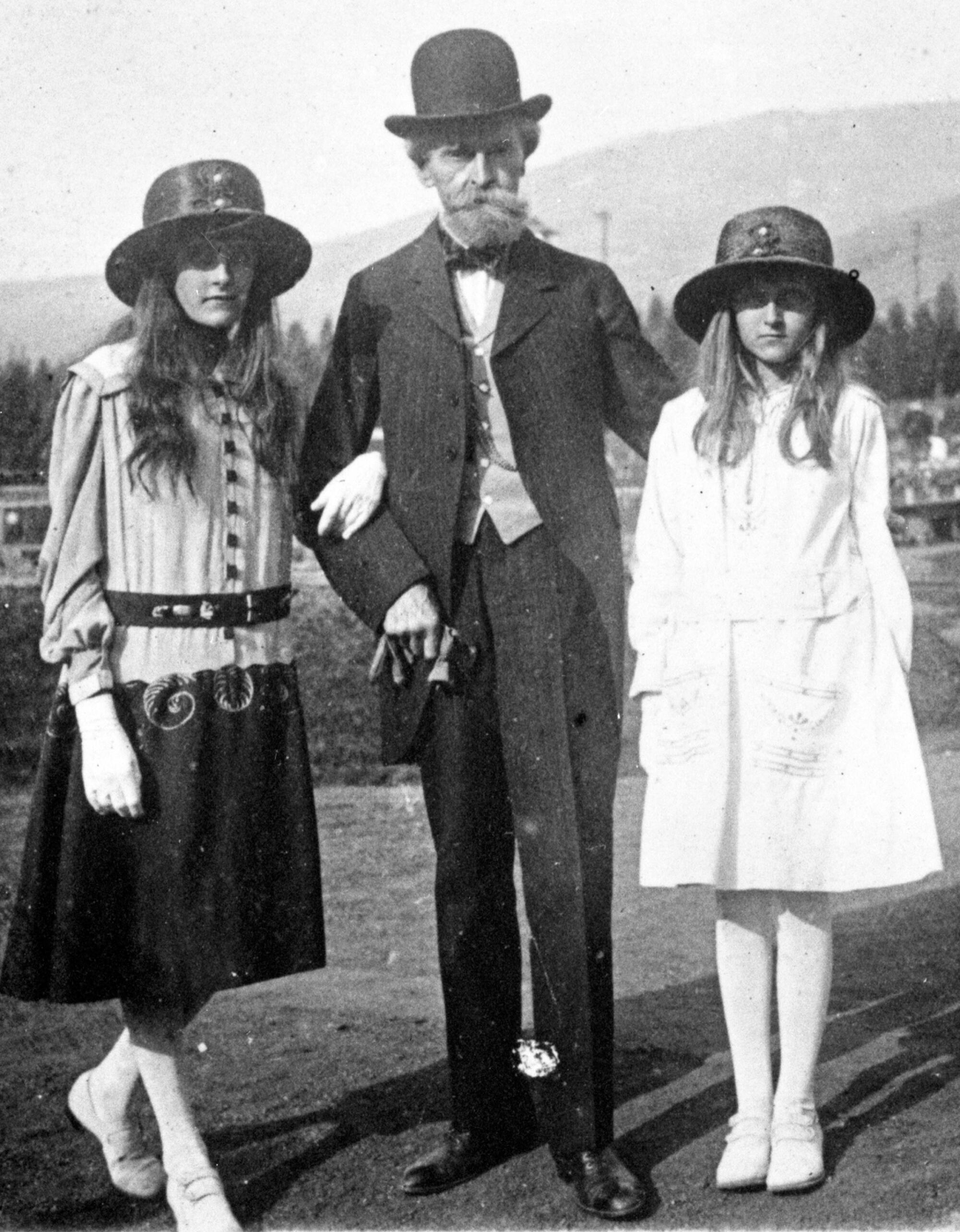

The first answer is copper, mined, sold and leveraged by a slight, bearded man named William Andrews Clark.

Clark (1839-1925), born in a Pennsylvania log cabin, got rich in copper mining and built his first mansion in Butte, Mont. Later he built a railroad from Los Angeles to Salt Lake City, opened banks, mined more copper in Arizona, co-founded Las Vegas (seat of Clark County) and built another mansion, a 121-room behemoth on Fifth Avenue in Manhattan. (It has since been razed.)

Clark and daughters Andrée, left, and Huguette visit Columbia Gardens, which he built in Butte, Mont. It was about 1917.

(Montana Historical Society)

“He’s one of the richest men that nobody’s ever heard of,” McClelland told the visitors.

Along the way Clark got married, fathered seven children, lost his first wife to typhoid fever, remarried in his 60s and fathered two additional daughters. He also got caught bribing Montana state legislators, yet served a term as U.S. senator from that state. And his name does endure here and there.

His son, William Andrews Clark Jr., made the donations that started UCLA’s William Andrews Clark Memorial Library. Also, you could say the senior Clark inspired Mark Twain.

Clark, Twain wrote, “is as rotten a human being as can be found anywhere under the flag; he is a shame to the American nation, and no one has helped to send him to the Senate who did not know that his proper place was the penitentiary, with a ball and chain on his legs.”

Much of the Bellosguardo story, however, is about the next generation of Clarks. As the group advanced through the house, admiring custom chandeliers and golden bathroom fixtures, the docents pushed the narrative forward.

A custom-made chandelier dangles in the library of the Bellosguardo Estate in Santa Barbara.

(Christopher Reynolds / Los Angeles Times)

Bellosguardo Estate, Santa Barbara.

(Christopher Reynolds / Los Angeles Times)

By summer 1923, when Clark and his second wife, Anna, arrived as renters at this 23-acre property above East Beach, he was one of the world’s wealthiest men. But he was in his mid-80s, 39 years older than Anna. Four years earlier, the couple had lost their older daughter, 16-year-old Andrée, to meningitis. Their surviving daughter, Huguette Clark, was now 17.

The Santa Barbara summer went well. By year’s end, the Clarks had bought the place for $300,000. But less than two years later, Clark died, leaving Anna and Huguette with a chunk of his fortune, the Santa Barbara property and the Italianiate villa that stood upon it, nicknamed Bellosguardo, or Pretty View.

So why, then, do visitors today walk through a French palace and not an Italian villa?

Because in 1933, as the country struggled with the Great Depression, Anna and Huguette Clark decided to level the villa (which had been damaged by a 1925 earthquake) and start over. Since they had lived several years in Paris and often spoke French to each other, they liked the idea of something French — a notable change from the Spanish Colonial projects popping up all over Santa Barbara.

Architect Reginald D. Johnson, designer of the Biltmore hotel in Montecito, delivered a rigorously symmetrical gray stone building (including one door that opens to nowhere) that paid minimal attention to ocean views. Two stories, 27 rooms, 13 fireplaces.

A sculpture in Santa Barbara’s Bellosguardo Estate shows Andrée Clark, a daughter of copper mogul William Andrews Clark who died in her teens. (Christopher Reynolds / Los Angeles Times)

Santa Barbara’s Bellosguardo Estate include an art studio full of paintings by and of heiress Huguette Clark, who is seen in the work on the easel. (Christopher Reynolds / Los Angeles Times)

Grounds, Bellosguardo Estate, Santa Barbara.

(Christopher Reynolds / Los Angeles Times)

It’s subdued, but not dull. As visitors see, there’s a circular women’s powder room. Carved maple panels line walls in one room, while 160 carved oak panels dominate another. The building wraps around a stately pond, much of the furniture dates to the 18th century and the walls are hung with paintings of the French countryside and, in just about every room, portraits of Andrée and Huguette as doe-eyed girls.

“Reminds me of Hearst Castle,” said visitor Cherie Visconti, eyeing the dining room.

On the library shelves, Voltaire and George Eliot are joined by Agatha Christie and Erle Stanley Gardner, the Ventura lawyer and author who created Perry Mason.

The Clarks never lived here full time. By the foundation’s estimation, the mother and daughter made 14 visits (by train) between 1936 and 1953, staying about 18 months in all.

On those stays, Huguette, known for being shy but smart, played piano and violin, collected dolls and painted, including many portraits and still lives now hanging under the high ceilings of the mansion’s art studio. Having been married and quickly divorced in her 20s, Huguette didn’t date much.

Anna, an accomplished musician, played the harp and sponsored a string quartet (whom she outfitted with Stradivarius instruments).

Dining room, Bellosguardo Estate, Santa Barbara. (Christopher Reynolds / Los Angeles Times)

Portraits in the Music room of Santa Barbara’s Bellosguardo Estate include a piano-top photograph of heiress Huguette Clark. She is also shown in the oil painting in the background. (Christopher Reynolds / Los Angeles Times)

But by 1953, Anna Clark’s health had become too delicate for the train ride west, and Huguette stayed east as well. After Anna Clark died in 1963, Huguette, now in her 50s, continued to stay away. Later, she said that Bellosguardo held so many reminders of her absent mother that it made her sad. But not sad enough to let it go.

Now without her sister, father, mother, partner or a job, Huguette kept more to herself. She took pleasure in commissioning dolls and dollhouses, sending gifts to artisans, employees and their children. She checked photographs to make sure that staffers were keeping Bellosguardo unchanged, from the doghouse (whose occupant had died years before) to the 1933 Cadillac limousine and Chrysler convertible in the garage.

Then, one day in 1991, after a long spell without medical care, she summoned a doctor to her 42-room New York apartment (which was really three apartments combined). He arrived to find a wraith in her 80s, down to 75 pounds, suffering from multiple cancers that had disfigured her face.

Yet she survived. Once Huguette had been transported to a New York hospital, she responded well to surgeries. Choosing to remain in the hospital and rejecting all suggestions that she move home, she regained her health and lasted until her death more than 20 years, shortly before her 105th birthday.

For all those years, she not only left Bellosguardo empty but also a Connecticut mansion and the Manhattan apartment. From her hospital room, she bought more dolls, commissioned dollhouses, bid at auctions and rebuffed hospital officials when they pressed too often for donations. Meanwhile, she traded calls and letters with friends and employees, showering gifts on her favorites.

Grounds, Bellosguardo Estate, Santa Barbara.

(Christopher Reynolds / Los Angeles Times)

Over those last 20 years, authors Dedman and Newell write, Huguette spent an estimated $30 million on gifts (including six homes) for her day nurse, Hadassah Peri, who routinely worked seven-day weeks.

In many respects, they wrote, the Clark family saga is a classic folk tale — “except told in reverse, with the bags full of gold arriving at the beginning, the handsome prince fleeing and the king’s daughter locking herself away in the tower.”

The fighting over her estate persisted for years (she left two wills). In time, the Bellosguardo Foundation was created to operate the Santa Barbara mansion as an arts center. To some degree, this is par for the course in the neighborhood. Casa del Herrero in nearby Montecito has been hosting visitors for years, as has Lotusland, renowned for its gardens. But years passed before the first Bellosguardo tours happened, a delay that sparked complaints from some in Santa Barbara.

Now, the foundation director and docents say, an expansion of the tours is at hand.

Foundation Executive Director Jeremy Lindaman estimated that 100 to 150 people take tours each week. Others visit as part of occasional special events, such as a flamenco dance presentation that took place on the grounds last month during Santa Barbara’s Old Spanish Days Fiesta.

Bellosguardo tours

What: 90-minute tours led by a volunteer docent. Visitors must be at least 14, and no indoor photography is allowed.

When: Usually offered Wednesdays through Sundays, two or three per day.

Where: Bellosguardo, 1407 E. Cabrillo Blvd., Santa Barbara

Cost: $100

Info: For details and to sign up to be notified of tour openings, visit the Bellosguardo Foundation website

By late fall, Lindaman said, he’s hoping to add a second tour that covers the mansion’s more intimate quarters, including bedrooms and service areas. A coffee-table book is in the works, as well.

“Everything that was here when she died is still here,” Lindaman said.

But booking a tour is a two-step exercise. Instead of offering direct booking through the Bellosguardo website, the foundation asks would-be visitors to sign up for notification. Every two months, an email goes out and tour slots fill quickly.

Thanks in part to this process and the price, Bellosguardo remains a well-kept half-secret. For many in Santa Barbara, the family’s most visible legacy is not the mansion but the Andrée Clark Bird Refuge, a 42-area city park and lagoon just north of Bellosguardo, that Huguette Clark paid to create and maintain in her sister’s name.

Yet among those who get inside Bellosguardo’s gates, Huguette Clark and her family are still sparking speculation.

Walking the rooms, “You just feel that family,” said Penny Simmons. “Sad things happened around here.”

“I didn’t know she was such a fine artist,” Patti Gibbs said at the end of her tour.

“We think she lived the life she wanted to live,” said her docent guide, McClelland.

“She was not crazy,” said Peter Higgins of Oxnard. “She knew what she was doing right up until the end.”

-

Minnesota1 week ago

Minnesota1 week agoReaders and writers: Plenty of thrills and danger in these Minnesota author’s mysteries

-

Technology6 days ago

Technology6 days agoBreakthrough robo-glove gives you superhuman grip

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoVideo: Biden Delivers Keynote on First Night of D.N.C.

-

Connecticut4 days ago

Connecticut4 days agoOxford church provides sanctuary during Sunday's damaging storm

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoVideo: Protesters Clash With Police Near the Democratic National Convention

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoNigeria police working to secure release of 20 kidnapped medical students

-

Politics1 week ago

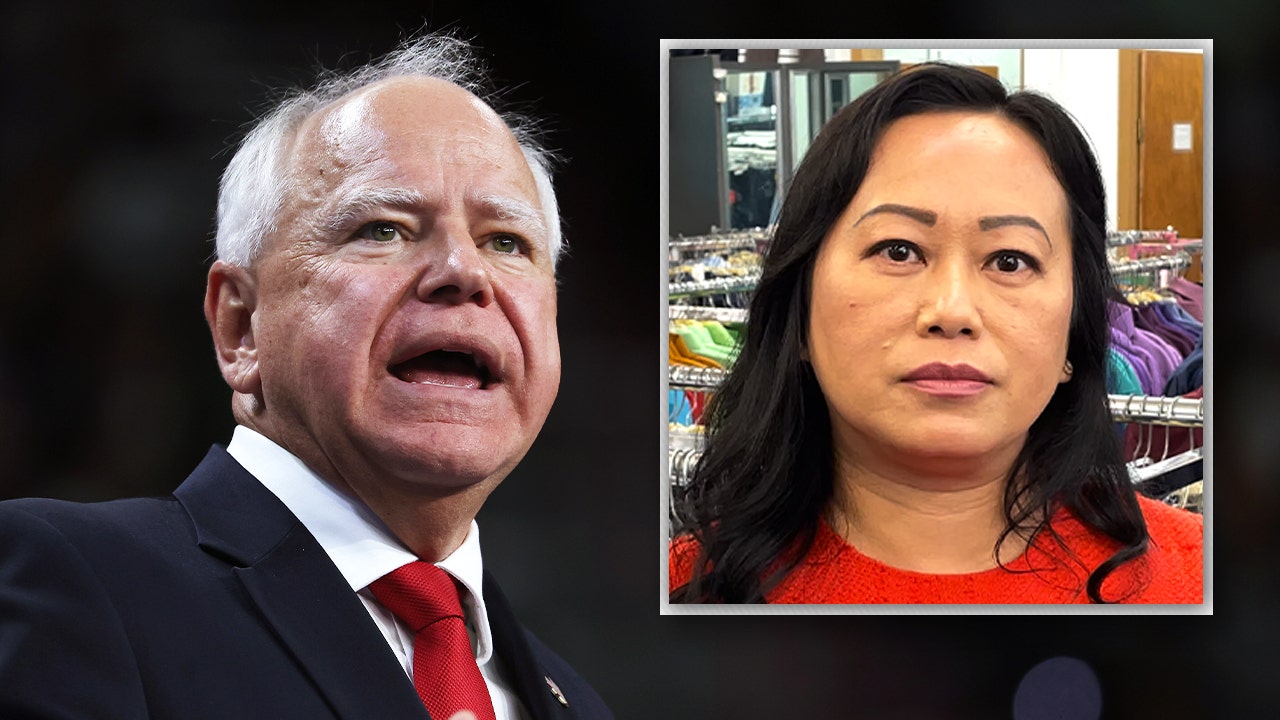

Politics1 week agoFormer teacher reveals which students suffered 'the most' under Walz's pandemic-era guidelines

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoDem strategists say Harris needs to ensure she's 'striking the right balance' at DNC, seize on 'momentum'