Health

One Family’s Toxic Train Wreck Ordeal: Illness, Exile and Debt

When Jessica Albright returned with her family to their home in East Palestine, Ohio, last month after four months away, she opened the car door and took a deep breath — then stopped and thought: Maybe not too deep. Hauling suitcases up the steps, she tried to discern whether the acrid scent in the air had lessened.

The mother of three could not be certain — of the smell, of its effects or of the correct next steps for her family. After a train carrying toxic chemicals derailed a half-mile from the Albrights’ house in February, a series of mysterious health symptoms forced Ms. Albright; her husband, Chris, and two of their daughters to move to a hotel room in Pennsylvania 20 miles away.

Now, they were back, not because their health issues had resolved, or because the house had been proven free of contaminants. They were back because they had $41 left in their savings account and felt they had no other choice.

Despite several weeks of intense focus, national attention has long since shifted away from East Palestine, where the Ohio governor has declared the air and water safe, and the Environmental Protection Agency has cited “no evidence to suggest there is contamination of concern.” Schools reopened, the town held its annual street fair, and when summer came, the picnic tables at The Dairy Mill soft-serve stand were crowded once more.

But 200 cleanup workers still arrive each day, working on the 1.4 million gallons of liquid wastewater and 3,293 tons of excavated soil that, according to the Ohio E.P.A., must still be removed. Earlier this summer, independent researchers warned of chemical contamination in buildings near the derailment site. Hundreds of people have reported symptoms associated with the derailment in recent months. And lawmakers have been flooded with calls and emails from residents and business owners who say they cannot enter their buildings for more than a few minutes without getting headaches.

The derailment and burning of the train’s toxic freight generated hundreds of unknown compounds, scientists say. However, linking any health issues directly to the toxins is difficult, since even the ones detected are not fully understood. Six months later, residents still have little information about how they might be affected by any lingering chemicals, making it impossible to assess long-term risks.

Ms. Albright, 43, contemplated this as she unpacked toiletries in a house that no longer felt like home, in a town that had become deeply divided with infighting and conspiracy theories.

For her, as for many, the uncertainty transcended the question of whether the air, soil, and water were toxic, to a personal one: For a family in the throes of medical, emotional and financial crisis, what would come next?

Night of fire

The little brick house on East Main Street was where two families had become one. The home was where Ms. Albright raised Kaedance, now 20, and Lainy, 17; where Chris Albright, 48, had moved in and become the girls’ stepdad almost a decade ago; where he and Ms. Albright brought their newborn daughter, Evy, now 8, home from the hospital.

Until six months ago, Mr. Albright left early each day to work as a foreman on a gas pipeline. Mrs. Albright worked as a case manager for students with special needs and as an office manager at a local gym. Kaedance had transferred to a nearby campus so that she could live with her family; Lainy was hoping to become cheerleading captain. Evy, already at an 11-year-old reading level, was teaching herself to use FaceTime while spinning circles on a hoverboard in the living room.

On Feb. 3, after a high school basketball game, Lainy saw something on Snapchat about a fire. When Ms. Albright took their dogs, Maggie and Stanley, into the yard before bed, she smelled burning plastic, peered around the front of the house and froze: She could see the flames.

Mr. Albright told her to leave with the girls. He stayed, but police came by twice and warned, “If it gets bad, we aren’t coming back.” So he took his pickup truck and fled, too.

After they left, Norfolk Southern officials grew concerned about a chemical reaction that could send shrapnel into neighborhoods. Losing daylight, the company gave the fire chief 13 minutes to decide whether to vent and burn: Dig ditches, rig the cars with explosives, and light the contents on fire. “Blindsided,” he said, he agreed.

Within two days of the intentional burn, Gov. Mike DeWine of Ohio declared East Palestine safe. Air quality samples measured contaminants “below safety screening levels,” and residents could return, he said — so, that evening, the Albrights did.

“The birds have started singing again,” Ms. Albright said in an interview that week, “a natural indicator that things are getting better.”

She had heard rumors of government cover-ups, and when she put her girls to bed each night, she found herself worrying about potential long-term effects, like cancer — but when schools reopened, she sent them back.

“For them,” she said, “we’re just wanting to keep things as normal as possible.”

Nausea, headaches and breathing trouble

The first signs that their lives would be far from normal appeared in Mr. Albright’s primary care doctor’s notes, after his appointment on Feb. 22:

His appetite is down over the past few weeks.

Yesterday morning he had some dry heaving.

This morning he vomited while he was in the shower.

Some difficulties in taking deep breaths.

Mr. Albright had no medical history of concern. Certainly seems to have some symptoms that correspond to the recent train derailment and vinyl chloride spill, Dr. Jason Rodriguez wrote. He prescribed an albuterol inhaler and gave Mr. Albright the phone number for the county health department.

Mr. Albright didn’t know, but the day before his medical appointment, a group of researchers from Carnegie Mellon and Texas A&M universities had driven past his house in a van, testing the ambient air with a mass spectrometer. The device detected acrolein, a chemical irritant that slows breathing and causes burning in the nose and throat, at a level six times higher than normal. Animal studies show that long-term exposure to acrolein can cause nasal lesions or damage to the lining of the lungs.

The consulting firm hired by Norfolk Southern, meanwhile, had been testing houses for contamination using a hand-held device that could not detect some chemicals at specific thresholds. At one building, about eight blocks from the Albrights’ house, the firm reported “no detection” five times, despite a “super glue” smell so pungent that the staff fled the premises.

“The air monitoring team left within 10 minutes, due to the unpleasant/overwhelming odor,” one of the inspectors wrote in documents provided to the E.P.A. and obtained by The Times.

The building’s owner ordered private testing for $900. It detected butyl acrylate — a compound used to make paints and plastics and that causes respiratory irritation and breathing difficulty — among other chemicals, and enough soot for the insurance company to declare the contents of the space a total loss.

But no one offered to test the Albrights’ house, and the family could not afford private testing. Instead, the family read a statement from the governor on Feb. 26: The E.P.A. had “conducted indoor air testing at a total of 578 homes. No contaminants associated with the derailment were detected.”

The air seemed much clearer in Meadville, Pa., about 80 miles northeast, where Mr. and Ms. Albright took Evy to an overnight hockey tournament on March 4, and Mr. Albright felt significantly better there. When they returned home, the odor was stifling.

Ms. Albright tracked everyone’s symptoms in a pocket calendar: Evy had a cough, sore throat and nausea. Lainy had eye irritation and a headache. Mr. Albright felt as if he couldn’t breathe.

That week, seven field workers from the federal Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry fell ill while doing door-to-door community surveys near the Albrights, according to federal incident reports reviewed by The Times. They experienced many of the same symptoms — sore throats, headaches and nausea — and were sent back to their hotel to recover. The incident was kept private.

Two weeks later, Mr. Albright’s doctor scheduled him for an X-ray and CT scan of his chest, which showed fluid collecting in his lungs.

4 people, 2 dogs, 1 hotel room

On a Friday in March, while Mr. Albright was vomiting, Ms. Albright heard a rumor that Norfolk Southern would reimburse East Palestine residents for the cost of a hotel room. They left town immediately for Monaca, Pa., a half-hour drive just across the Ohio River, moving into a 400-square-foot room in a turquoise and brown hotel tucked behind a self-storage warehouse and a farm equipment supplier called Rural King.

Home2 Suites was among the only hotels that would accept 60-pound dogs, and it cost $235 per night. They got a $23 discount after a month, when they were considered residents. Norfolk Southern gave them $1,000 on a prepaid card upfront — enough for three nights — but for the more than 100 nights that followed, Ms. Albright traveled to the Norfolk Southern Family Assistance Center in East Palestine on a biweekly basis to have hotel bills reimbursed after the fact. The final cost was more than $22,000.

A spokesman for Norfolk Southern said that he could not comment on the family’s specific arrangement but that the train company routinely worked with families to pay hotel bills upfront for those who requested it.

“Norfolk Southern remains committed to making it right for the residents of East Palestine and surrounding communities,” he said, including making reimbursements for groceries, gas and other items to people who temporarily relocated.

The 40-mile round trip to the East Palestine schools was too far of a commute before Ms. Albright’s shifts, so Evy did worksheets from the hotel bed in Room #311 and took spelling tests on Zoom once a week. She kept in touch with her best friends, Jordyn and Braelynn, through an iPad gaming platform Roblox. Lainy taught herself pre-calculus and anatomy; her 11th grade U.S. government class couldn’t be taken virtually, so her teacher referred her to a college-level personal finance class instead. (Kaedance stayed with her boyfriend’s family to be closer to work and school.)

The family bought a $6 griddle to make grilled cheese sandwiches and used the hotel room microwave to make ramen — until Evy forgot to add water one evening and almost set the room on fire. Some nights, they ate McDonalds, or they waited until after 9 p.m., when they could get wings at Primanti Brothers for half-price.

Before dawn on March 28, Mr. Albright went to Pittsburgh for an echocardiogram. The results were crushing.

Markedly dilated ventricle, a cardiologist’s follow-up notes read. His ejection fraction, or the percentage of blood being pumped out with each heartbeat, — normally 50 percent or higher — was down to about 15 percent.

The doctor ordered a catheterization; Mr. Albright would be admitted overnight and fitted with a LifeVest, a round-the-clock external defibrillator for people at risk of sudden cardiac death.

Mr. Albright’s cardiologist, Dr. Matthew M. Lander, said it was unlikely that the toxins in East Palestine had wholly caused Mr. Albright’s heart failure. Still, given the rapid deterioration, Dr. Lander was confident that the chemicals — or the stress — had likely exacerbated the condition.

“I would be hard-pressed to think this is not related,” he said in an interview.

Lainy, already reeling from the cramped hotel room and social isolation, took her father’s news especially hard. She begged her mother to drive an hour to the high school, where a teacher pulled her aside. Lainy broke down. She needed a therapist, she said, but her mother couldn’t find one since her insurance policy was through Ohio, but they were staying in Pennsylvania.

For one week in May, Ms. Albright tried dropping Lainy off at the East Palestine house each morning before work, so she could catch a ride to school. Within 10 minutes, Lainy always had a gushing nosebleed — five times in one week.

Mr. Albright took Lainy to Applebee’s, just the two of them, and before her buffalo chicken tenders were at the table, he looked her in the eyes. “I’m not going anywhere — I’m going to be around, you know,” he remembers saying. “Just so I can keep bugging you.”

With Evy, he used fewer words, taking her out of the hotel every few days to fish for bluegill and rainbow trout at Brush Creek in Beaver Falls, Pa. He wanted to make for normal summer nights together. He taught her to cast, watch, reel. More than anything, he said, he wanted to teach her patience.

They often sat in silence, Evy fidgeting and Mr. Albright trying to forget the image of the 3,500 fish that had been floating, dead, in the streams back home.

“Evy knows,” Mr. Albright said, “but only what a 7-year-old should know.”

Financial crisis

Ms. Albright hardly had time to process her husband’s diagnosis. Financial constraints were beginning to suffocate them.

The pipelining company wasn’t willing to bring Mr. Albright back to work while he was wearing a LifeVest — too much of a liability — and agencies in Ohio and Pennsylvania bounced his unemployment claim back and forth for months. Ms. Albright tried to generate enough income from her two jobs to get by.

The family still owed monthly rent on their East Palestine house. Comcast kept sending bills, despite the vacancy. And while Norfolk Southern continued to reimburse hotel bills, the Albrights didn’t have enough cash to pay upfront.

One afternoon, at Norfolk Southern’s assistance center, Ms. Albright found herself pleading for help from an unsympathetic staffer. She burst into tears.

“I felt so dehumanized,” she wrote in a text to The New York Times.

No mother would choose a life for her children of burned ramen in a one-room home, she thought. But now, she couldn’t even choose that.

She knew the family needed to return to the East Palestine house, and she went first. Between her shifts, she ripped up the carpets and hauled them into the basement; bundled curtains and clothing into trash bags; brushed away the strange powdery substance that kept collecting on Evy’s playhouse.

It was she, not her husband, who ended up in the emergency room, in late May with stroke-level blood pressure. She had no medical history; her doctor suspected stress. She was given two medications and went back to work.

The community that the Albrights returned to last month was nothing like the one they had left. The main road into town was restricted — reserved for cleanup crews with badges — and two massive blue vats of potentially contaminated water had been erected downtown. The family’s street was dotted with “For Sale” signs, moving trucks, vacant houses.

Their tiny town, long divided by a railroad track, was now divided over what was worse: ignoring the potential health effects or risking economic disaster, as property values and small businesses grew weaker the longer the fiasco wore on.

The yard banners that had declared, “The greatest comeback story in American history” and “E.P. will not be derailed,” were mostly gone. Instead, neighbors and relatives were no longer speaking. Some people suspected — hoped — that families like the Albrights were simply paranoid and psychosomatic. Others openly speculated that they were faking their symptoms to get more cash from Norfolk Southern.

“A bunch of gold diggers trying to ack like they have chemist degrees,” one resident wrote on an online message board. “Your nothing but a embarrassment to East Palestine.”

Andrew J. Whelton, an environmental engineer who has led six field investigations to East Palestine since the derailment and has urged the E.P.A. and lawmakers to act, believes that chemical contamination inside buildings is still acute. In his view, the E.P.A. — the official incident commander of the recovery efforts — has too often deferred to Norfolk Southern and its consulting firm on key aspects of chemical surveillance.

“It’s not unusual that we’re seeing this pollution,” he said in an interview. “What is unusual, though, is the government turning a blind eye to this and allowing it to continue.”

The E.P.A. did not respond to multiple requests for a response but has maintained in recent public statements that “there is no evidence to suggest there is contamination of concern inside structures.”

One of the first mornings back, Evy pattered into the kitchen barefoot, weaving around boxes, negotiating with her parents whether she really did need to brush her hair. The rising sun caught her blue eyes through the window, as she nestled her head into her father’s chest, listening to his heart, reciting the steps she should take if the LifeVest were to sound.

At 7 a.m., they left for Pittsburgh — for another medical appointment — where Mr. Albright’s new cardiologist would tell him that several medication dosages would need to be increased, that there would be a $30 co-pay, more restrictions and more testing.

That night at home, Evy would crawl into her parents’ bed and fall asleep with an air purifier humming nearby.

It doesn’t do much to help the odor, they said, but it does drown out the trains.

Health

Bill Gates reveals 'next phase of Alzheimer's fight' as he shares dad's personal battle

NEWYou can now listen to Fox News articles!

Bill Gates is speaking out about his personal experience with Alzheimer’s — and his hope for progress in fighting the disease.

In an essay published this week on his blog at GatesNotes.com, the Microsoft co-founder and tech billionaire, 69, reflected on the difficulty of spending another Father’s Day without his dad, Bill Gates Sr.

The elder Gates passed away in 2020 at the age of 94 after battling Alzheimer’s.

RATES OF DEMENTIA ARE LOWER IN PEOPLE WHO EAT THIS SPECIFIC DIET, RESEARCH SHOWS

“It was a brutal experience, watching my brilliant, loving father go downhill and disappear,” Gates wrote in the blog post.

Today, motivated by his own experience with the common dementia, Gates — who serves as chair of the Gates Foundation — is committed to working toward a cure for the common dementia, which currently affects more than seven million Americans, or one in nine people over 65.

Bill Gates and Bill Gates Sr. pose in a meeting room at the Seattle headquarters of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation in 2008. (Gates Ventures)

In his blog, Gates expressed optimism about the “massive progress” being made in the fight against Alzheimer’s and other dementias.

Last year, Gates said he visited Indiana University’s School of Medicine in Indianapolis to tour the labs where teams have been researching Alzheimer’s biomarkers.

BILL GATES LIKELY HAD AUTISM AS A CHILD, HE REVEALS: ‘WASN’T WIDELY UNDERSTOOD’

“I also got the opportunity to look under the hood of new automated machines that will soon be running diagnostics around the world,” he wrote. “It’s an exciting time in a challenging space.”

One of the biggest breakthroughs in Alzheimer’s research, according to Gates, is blood-based diagnostic tests, which detect the ratio of amyloid plaques in the brain. (Amyloid plaques, clumps of protein that accumulate in the brain, are one of the hallmarks of Alzheimer’s.)

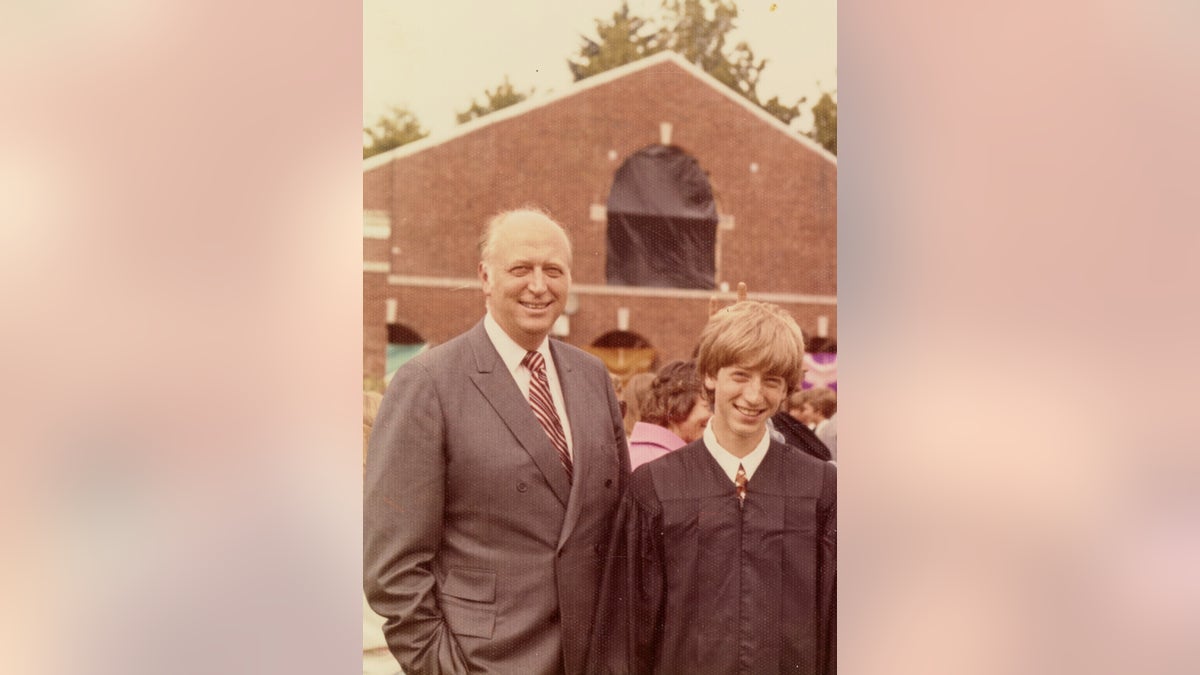

Bill Gates Jr. (right) poses with his father at his graduation ceremony in 1973. (Gates family)

“I’m optimistic that these tests will be a game-changer,” Gates wrote.

Last month, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the first blood-based test for patients 55 years and older, as Fox News Digital reported at the time.

“A simple, accurate and easy-to-run blood test might one day make routine screening possible.”

Traditionally, Gates noted, the primary path to Alzheimer’s diagnosis was either a PET scan (medical imaging) or spinal tap (lumbar puncture), which were usually only performed when symptoms emerged.

The hope is that blood-based tests could do a better job of catching the disease early, decline begins.

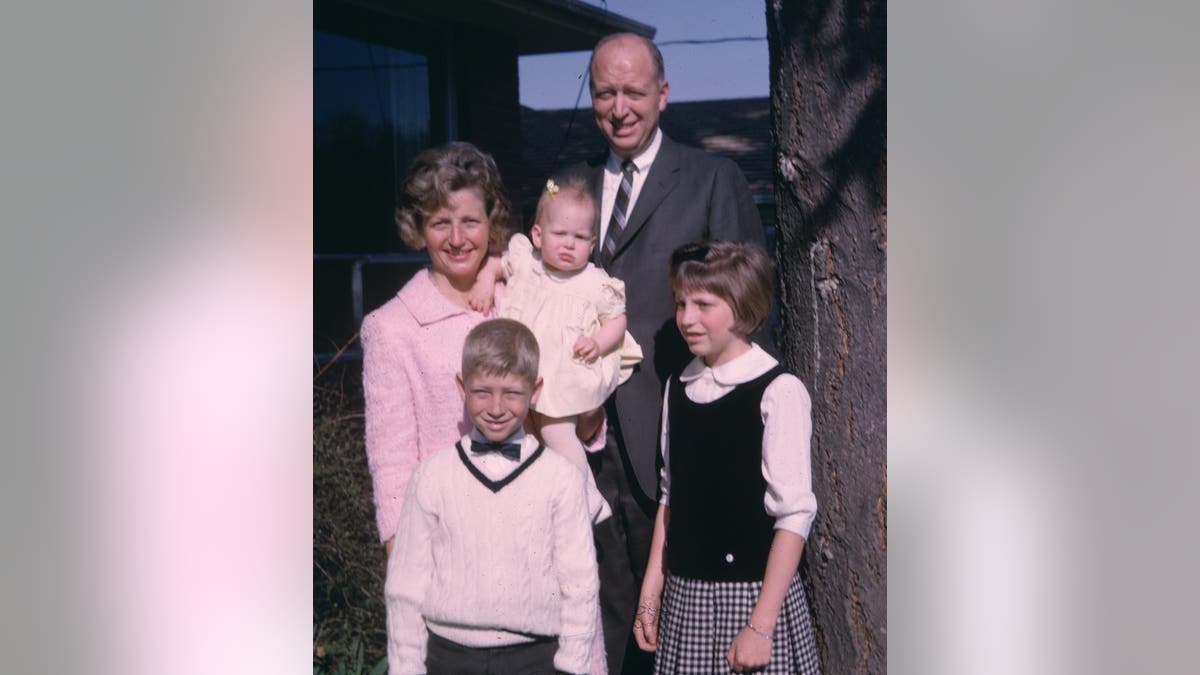

The Gates family poses for a photo in 1965. The elder Gates passed away in 2020 at the age of 94 after battling Alzheimer’s. (Gates family)

“We now know that the disease begins 15 to 20 years before you start to see any signs,” Gates wrote.

“A simple, accurate and easy-to-run blood test might one day make routine screening possible, identifying patients long before they experience cognitive decline,” he stated.

Gates said he is often asked, “What is the point of getting diagnosed if I can’t do anything about it?”

To that end, he expressed his optimism for the future of Alzheimer’s treatments, noting that two drugs — Lecanemab (Leqembi) and Donanemab (Kisunla) — have gained FDA approval.

“Both have proven to modestly slow down the progression of the disease, but what I’m really excited about is their potential when paired with an early diagnostic,” Gates noted.

Alzheimer’s disease currently affects more than seven million Americans, or one in nine people over 65. (iStock)

He said he is also hopeful that the blood tests will help speed up the process of enrolling patients in clinical trials for new Alzheimer’s drugs.

To accomplish this, Gates is calling for increased funding for research, which often comes from federal grants.

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP FOR OUR HEALTH NEWSLETTER

“This is the moment to spend more money on research, not less,” he wrote, also stating that “the quest to stop Alzheimer’s has never had more momentum.”

“There is still a huge amount of work to be done — like deepening our understanding of the disease’s pathology and developing even better diagnostics,” Gates went on.

“I am blown away by how much we have learned about Alzheimer’s over the last couple of years.”

Gates pointed out that when his father had Alzheimer’s, it was considered a “death sentence,” but that is starting to change.

“I am blown away by how much we have learned about Alzheimer’s over the last couple of years,” he wrote.

For more Health articles, visit www.foxnews.com/health

“I cannot help but be filled with a sense of hope when I think of all the progress being made on Alzheimer’s, even with so many challenges happening around the world. We are closer than ever before to a world where no one has to watch someone they love suffer from this awful disease.”

Health

This Tropical Fruit May Improve Your Skin, Heart Health and More

Use left and right arrow keys to navigate between menu items.

Use escape to exit the menu.

Sign Up

Create a free account to access exclusive content, play games, solve puzzles, test your pop-culture knowledge and receive special offers.

Already have an account? Login

Health

FDA approves first twice-yearly injection that prevents HIV infection

FDA authorizes AI tool to predict breast cancer risk

Senior medical analyst Dr. Marc Siegel discusses advancements in artificial intelligence aimed at predicting an individual’s future risk of breast cancer and the increased health risks from cannabis as users age.

NEWYou can now listen to Fox News articles!

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved a new, twice-yearly shot — the first and only of its kind — to prevent HIV, the creator of the drug, Gilead Sciences, announced on Wednesday.

Sold under the name Yeztugo, the company’s injectable HIV-1 capsid inhibitor (lenacapavir) reduces the risk of sexually acquired HIV in adults and adolescents.

“This is a historic day in the decades-long fight against HIV,” said Daniel O’Day, chairman and CEO of California-based Gilead Sciences, in a press release.

ALZHEIMER’S DISEASE COULD BE PREVENTED BY ANTIVIRAL DRUG ALREADY ON MARKET

The medicine, which only needs to be administered twice a year, has shown “remarkable outcomes in clinical studies,” as Gilead claims it could transform HIV prevention.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has approved a new, twice-yearly shot, Yeztugo, to prevent HIV, the creator of the drug announced on Wednesday. (Gilead Sciences via AP)

The drug is given as an injectable under the skin that the body then slowly absorbs. Individuals must have a negative HIV-1 test prior to starting the treatment.

In large trials last year, the drug was not only nearly 100% effective in its prevention of HIV, but proved superior to once-daily oral medication like Truvada, another drug by Gilead.

The drug is given as an injectable under the skin that the body then slowly absorbs. Individuals must have a negative HIV-1 test prior to starting the treatment. (AP Photo/Nardus Engelbrecht)

The journal Science named lenacapavir its 2024 “Breakthrough of the Year.”

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP FOR OUR HEALTH NEWSLETTER

Lenacapavir uses a multi-stage approach that distinguishes it from other approved antiviral medications.

Sold under the name Yeztugo, the company’s injectable HIV-1 capsid inhibitor (lenacapavir) reduces the risk of sexually acquired HIV in adults and adolescents. (iStock)

“While most antivirals act on just one stage of viral replication, lenacapavir is designed to inhibit HIV at multiple stages of its lifecycle,” states the press release from Gilead.

For more Health articles, visit www.foxnews.com/health

“Yeztugo is one of the most important scientific breakthroughs of our time and offers a very real opportunity to help end the HIV epidemic,” O’Day said in the press release.

The most commonly reported adverse reactions during clinical trials included injection site reactions, headache and nausea, according to the company.

-

Business1 week ago

Business1 week agoYale’s Endowment Selling Private Equity Stakes as Trump Targets Ivies

-

Culture1 week ago

Culture1 week agoBarbara Holdridge, Whose Record Label Foretold Audiobooks, Dies at 95

-

Culture1 week ago

Culture1 week agoA Murdered Journalist’s Unfinished Book About the Amazon Gets Completed and Published

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoYosemite Bans Large Flags From El Capitan, Criminalizing Protests

-

Education1 week ago

Education1 week agoWhat Happens to Harvard if Trump Successfully Bars Its International Students?

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoFox News Politics Newsletter: Hillary ‘Can’t Handle the Ratio'

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoTrumps to Attend ‘Les Misérables’ at Kennedy Center

-

Arizona1 day ago

Arizona1 day agoSuspect in Arizona Rangers' death killed by Missouri troopers