Health

After End of Pandemic Coverage Guarantee, Texas Is Epicenter of Medicaid Losses

Juliette Vasquez gave birth to her daughter in June with the help of Medicaid, which she said had covered the prenatal medications and checkups that kept her pregnancy on track.

But as she cradled her daughter, Imani, in southwest Houston one afternoon this month, she described her fear of going without the health insurance that helped her deliver her baby.

This month, Ms. Vasquez, 27, joined the growing ranks of Americans whose lives have been disrupted by the unwinding of a policy that barred states from removing people from Medicaid during the coronavirus pandemic in exchange for additional federal funding.

Since the policy lifted at the beginning of April, over half a million people in Texas have been dropped from the program, more than any other state has reported removing so far, according to KFF, a health policy research organization. Health experts and state advocacy groups say that many of those in Texas who have lost coverage are young mothers like Ms. Vasquez or children who have few alternatives, if any, for obtaining affordable insurance.

Ms. Vasquez said that she needed to stay healthy while breastfeeding and be able to see a doctor if she falls ill. “When you are taking care of someone else, it’s very different,” she said of needing health insurance as a new parent.

Enrollment in Medicaid, a joint federal-state health insurance program for low-income people, soared to record levels while the pandemic-era policy was in place, and the nation’s uninsured rate fell to a record low early this year. But since the so-called unwinding began, states have reported dropping more than 4.5 million people from Medicaid, according to KFF.

That number will climb in the coming months. The Congressional Budget Office has estimated that more than 15 million people will be dropped from Medicaid over a year and a half and that more than six million of them will end up uninsured.

While some people like Ms. Vasquez are losing their coverage because they no longer meet the eligibility criteria, many others are being dropped for procedural reasons, suggesting that some people may be losing their insurance even though they still qualify for it.

The upheaval is especially acute in Texas and nine other states that have not adopted the Affordable Care Act’s expansion of Medicaid, all of which have state governments either partly or fully controlled by Republicans. Under the health law, states can expand their Medicaid programs to cover adults who earn up to 138 percent of the federal poverty level, or about $41,000 for a family of four.

But in Texas, which had the highest uninsured rate of any state in 2021, the Medicaid program is far more restrictive. Many of those with coverage are children, pregnant women or people with disabilities.

The ongoing unwinding has renewed concerns about the so-called coverage gap, in which some people in states that have not expanded Medicaid have incomes that are too high for the program but too low for subsidized coverage through the Affordable Care Act’s marketplaces.

“It’s going to lay bare the need for expansion, particularly when we see these very poor parents become uninsured and fall into the coverage gap and have nowhere to go,” said Joan Alker, the executive director of the Georgetown University Center for Children and Families.

Texas’ Medicaid program grew substantially during the pandemic when the state was barred from removing people from it. At the start of the unwinding, nearly six million Texans were enrolled in the program, or roughly one in five people in the state, up from nearly four million before the pandemic.

Now the program is shrinking significantly. Legacy Community Health, a network of clinics in and around Houston that offer low-cost health care to the uninsured, has been swamped in recent weeks by panicked parents whose children suddenly lost Medicaid coverage, said Adrian Buentello, a Legacy employee who helps patients with their health insurance eligibility forms.

“Moms are frantic,” he said. “They’re in distress. They want their child to have immunizations that are required, these annual exams that schools require.”

Texans are losing Medicaid for a variety of reasons. Some people now have incomes too high for their children to qualify, or they now earn too much to keep their own coverage. Some young adults have aged out of the program.

Some new mothers like Ms. Vasquez are losing coverage because they are two months out from having given birth, a stricter cutoff than in most states. Gov. Greg Abbott, a Republican, recently signed legislation extending postpartum coverage to a year, which would bring Texas in line with most of the country. But the new rule is not expected to go into effect until next year.

Kayla Montano, who gave birth in March, said she suffered from an umbilical hernia and pelvic pain from her pregnancy and was set to lose coverage at the end of this month, most likely falling into the coverage gap. A mother of three in Mission, Texas, Ms. Montano said she was working only part time so she could take care of her young children, a schedule that had left her ineligible to receive insurance from her employer.

“My health will be on hold until I start working full time again,” she said.

Health experts are particularly worried about the many Texans who are losing Medicaid coverage for procedural reasons, such as not returning paperwork to confirm their eligibility, even if they may still qualify for the program.

Of the 560,000 people whom Texas has reported removing from Medicaid during the first months of eligibility checks, about 450,000, or roughly 80 percent, were dropped for procedural reasons. Nationwide, in states where data is available, three-quarters of those who have lost Medicaid during the unwinding were removed from the program on procedural grounds, according to KFF.

In a statement, Tiffany Young, a spokeswoman for the Texas Health and Human Services Commission, which is overseeing the state’s unwinding process, said that Texas had prioritized conducting eligibility checks for those most likely to no longer be eligible for the program. She said the agency was using a range of tactics to try to reach people, including text messages, robocalls and community events.

Ms. Young said the first few months of eligibility checks had generally gone as expected, though she said the state was aware of some instances in which people had been wrongly removed from the program. “We’re working to reinstate coverage for those individuals as soon as possible,” she said.

Adrienne Lloyd, the health policy manager at the Texas branch of the Children’s Defense Fund, an advocacy group, said that because of its size and rural expanse, Texas was an especially difficult state for outreach to people whose coverage may be at risk.

Many rural residents lack steady internet access or nearby health department offices where they can seek help re-enrolling in Medicaid in person, Ms. Lloyd said, while a state hotline could have long wait times. Others, she said, might not be comfortable using technology to renew their coverage or could struggle to fill out paper forms.

The work required for those who do not enroll online or over the phone can be challenging. Early this month, Luz Amaya drove roughly 30 minutes to a branch of the Houston Food Bank for help filling out an application to re-enroll her children in Medicaid. Her arthritis had left her hands impaired, making the drive difficult, she said.

Ms. Amaya was among dozens of parents who visited the food bank for an event sponsored in part by the state that offered help with enrollment.

Ms. Amaya grew emotional at the event when she learned that her oldest daughter would soon age out of Medicaid and might no longer be able to get the therapy she needs. Ms. Amaya said she was there in part to confirm coverage for another daughter who needed therapy.

Another attendee, Mario Delgado, said he had come to re-enroll in Medicaid after he and his wife suddenly lost coverage around the beginning of the state’s unwinding. Both are disabled and cannot work, he said. With money tight, they have scraped together payments for medications.

His wife needs back surgery, he said, and he needs medication to keep up with his diabetes, which makes his hands swollen. “If you cry, the pain stays the same,” he said, describing the resignation they have felt struggling to afford health care.

He soon received good news. He and his wife were back on Medicaid. “I’ll sleep better,” he said as he exited the building into the scorching Texas summer heat.

Health experts have warned that many of those losing coverage in the unwinding may not realize their fate until they are informed by a health provider or billed for a medical service.

Perla Brown, the mother of a boy with autism, came to the food bank event soon after her son’s therapist told her that her child had lost Medicaid, she said. She soon discovered letters in the mail she had missed that had warned her of the imminent loss of his coverage. She said she was worried about paying the bill for the therapy appointment.

Ms. Vasquez, the new mother, said that having a child “just opens up your heart in a very different way.” She had learned to enjoy switching out her daughter’s blankets once they accrued too much spit. The way her daughter had learned to play on her stomach, she added, made her happy.

But the joy of her parenting, she said, had been dimmed by morbid thoughts about the consequences of losing her Medicaid. Health care, she said, “is always about the cost.”

Health

Bill Gates reveals 'next phase of Alzheimer's fight' as he shares dad's personal battle

NEWYou can now listen to Fox News articles!

Bill Gates is speaking out about his personal experience with Alzheimer’s — and his hope for progress in fighting the disease.

In an essay published this week on his blog at GatesNotes.com, the Microsoft co-founder and tech billionaire, 69, reflected on the difficulty of spending another Father’s Day without his dad, Bill Gates Sr.

The elder Gates passed away in 2020 at the age of 94 after battling Alzheimer’s.

RATES OF DEMENTIA ARE LOWER IN PEOPLE WHO EAT THIS SPECIFIC DIET, RESEARCH SHOWS

“It was a brutal experience, watching my brilliant, loving father go downhill and disappear,” Gates wrote in the blog post.

Today, motivated by his own experience with the common dementia, Gates — who serves as chair of the Gates Foundation — is committed to working toward a cure for the common dementia, which currently affects more than seven million Americans, or one in nine people over 65.

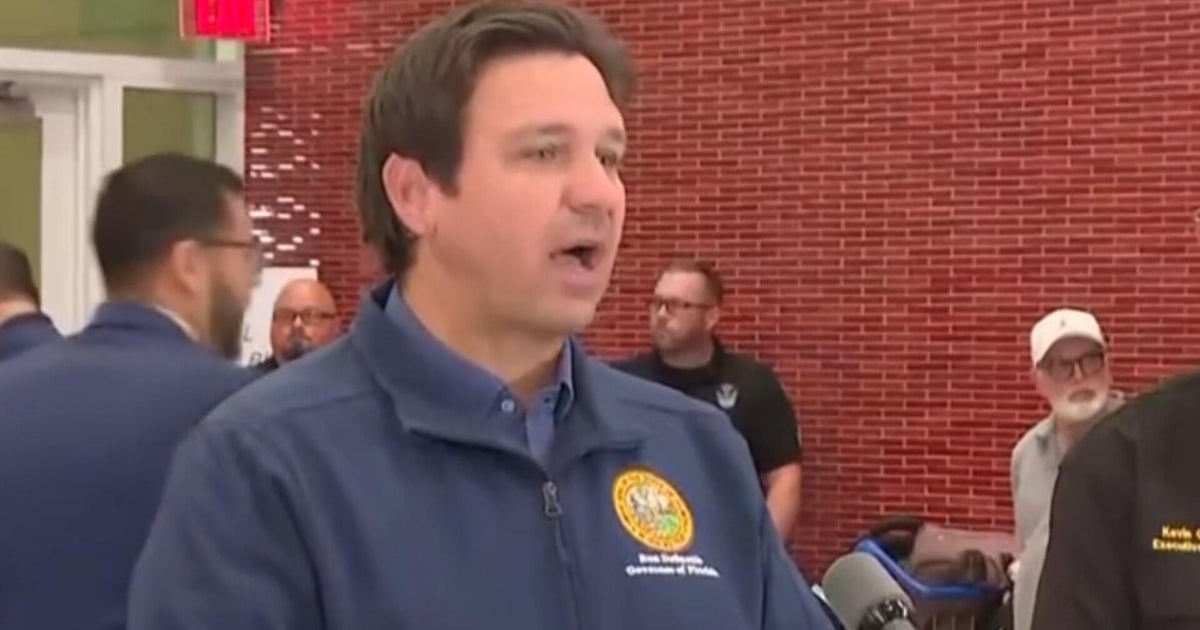

Bill Gates and Bill Gates Sr. pose in a meeting room at the Seattle headquarters of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation in 2008. (Gates Ventures)

In his blog, Gates expressed optimism about the “massive progress” being made in the fight against Alzheimer’s and other dementias.

Last year, Gates said he visited Indiana University’s School of Medicine in Indianapolis to tour the labs where teams have been researching Alzheimer’s biomarkers.

BILL GATES LIKELY HAD AUTISM AS A CHILD, HE REVEALS: ‘WASN’T WIDELY UNDERSTOOD’

“I also got the opportunity to look under the hood of new automated machines that will soon be running diagnostics around the world,” he wrote. “It’s an exciting time in a challenging space.”

One of the biggest breakthroughs in Alzheimer’s research, according to Gates, is blood-based diagnostic tests, which detect the ratio of amyloid plaques in the brain. (Amyloid plaques, clumps of protein that accumulate in the brain, are one of the hallmarks of Alzheimer’s.)

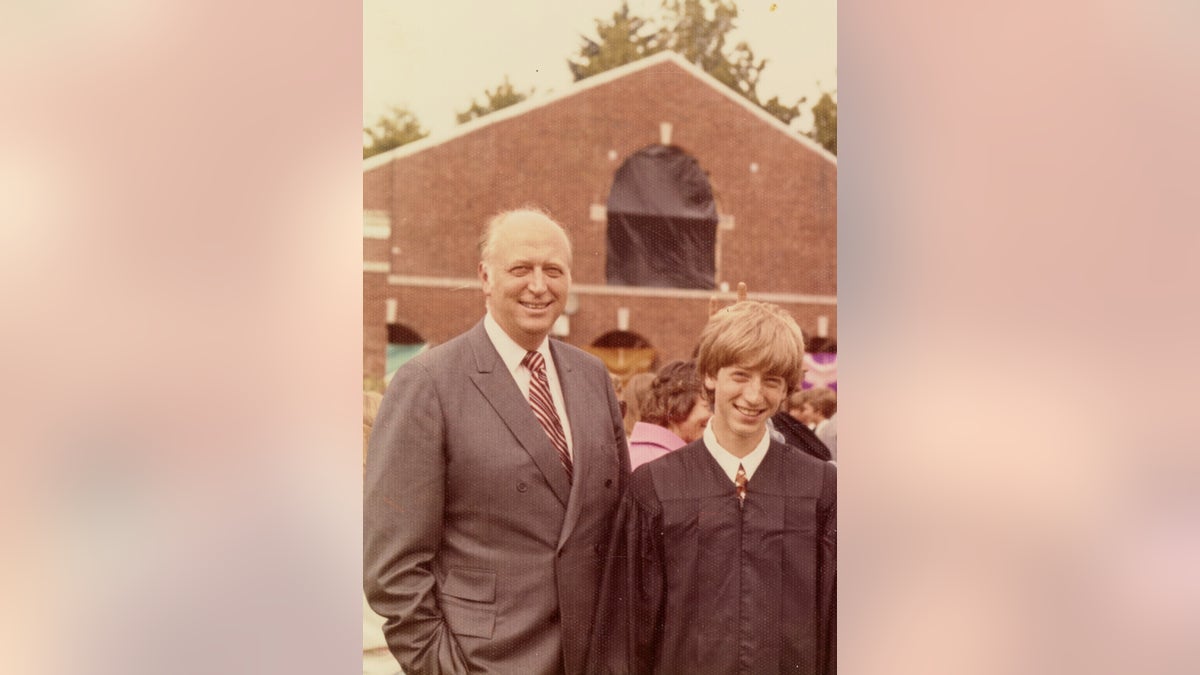

Bill Gates Jr. (right) poses with his father at his graduation ceremony in 1973. (Gates family)

“I’m optimistic that these tests will be a game-changer,” Gates wrote.

Last month, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the first blood-based test for patients 55 years and older, as Fox News Digital reported at the time.

“A simple, accurate and easy-to-run blood test might one day make routine screening possible.”

Traditionally, Gates noted, the primary path to Alzheimer’s diagnosis was either a PET scan (medical imaging) or spinal tap (lumbar puncture), which were usually only performed when symptoms emerged.

The hope is that blood-based tests could do a better job of catching the disease early, decline begins.

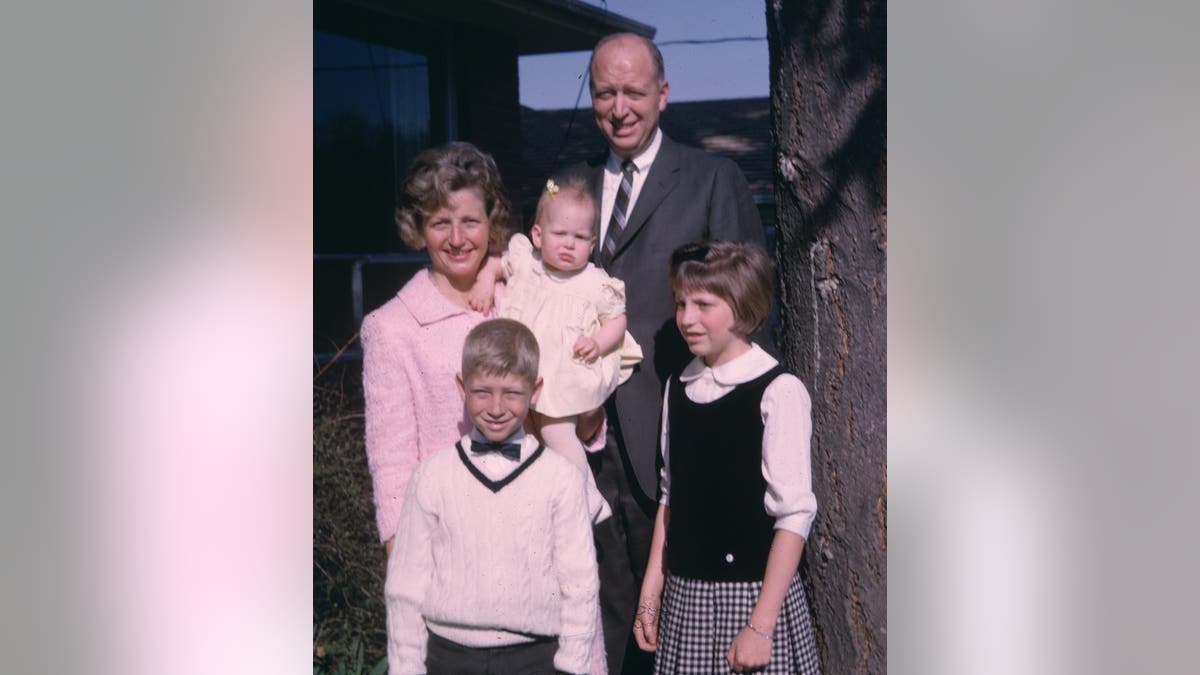

The Gates family poses for a photo in 1965. The elder Gates passed away in 2020 at the age of 94 after battling Alzheimer’s. (Gates family)

“We now know that the disease begins 15 to 20 years before you start to see any signs,” Gates wrote.

“A simple, accurate and easy-to-run blood test might one day make routine screening possible, identifying patients long before they experience cognitive decline,” he stated.

Gates said he is often asked, “What is the point of getting diagnosed if I can’t do anything about it?”

To that end, he expressed his optimism for the future of Alzheimer’s treatments, noting that two drugs — Lecanemab (Leqembi) and Donanemab (Kisunla) — have gained FDA approval.

“Both have proven to modestly slow down the progression of the disease, but what I’m really excited about is their potential when paired with an early diagnostic,” Gates noted.

Alzheimer’s disease currently affects more than seven million Americans, or one in nine people over 65. (iStock)

He said he is also hopeful that the blood tests will help speed up the process of enrolling patients in clinical trials for new Alzheimer’s drugs.

To accomplish this, Gates is calling for increased funding for research, which often comes from federal grants.

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP FOR OUR HEALTH NEWSLETTER

“This is the moment to spend more money on research, not less,” he wrote, also stating that “the quest to stop Alzheimer’s has never had more momentum.”

“There is still a huge amount of work to be done — like deepening our understanding of the disease’s pathology and developing even better diagnostics,” Gates went on.

“I am blown away by how much we have learned about Alzheimer’s over the last couple of years.”

Gates pointed out that when his father had Alzheimer’s, it was considered a “death sentence,” but that is starting to change.

“I am blown away by how much we have learned about Alzheimer’s over the last couple of years,” he wrote.

For more Health articles, visit www.foxnews.com/health

“I cannot help but be filled with a sense of hope when I think of all the progress being made on Alzheimer’s, even with so many challenges happening around the world. We are closer than ever before to a world where no one has to watch someone they love suffer from this awful disease.”

Health

This Tropical Fruit May Improve Your Skin, Heart Health and More

Use left and right arrow keys to navigate between menu items.

Use escape to exit the menu.

Sign Up

Create a free account to access exclusive content, play games, solve puzzles, test your pop-culture knowledge and receive special offers.

Already have an account? Login

Health

FDA approves first twice-yearly injection that prevents HIV infection

FDA authorizes AI tool to predict breast cancer risk

Senior medical analyst Dr. Marc Siegel discusses advancements in artificial intelligence aimed at predicting an individual’s future risk of breast cancer and the increased health risks from cannabis as users age.

NEWYou can now listen to Fox News articles!

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved a new, twice-yearly shot — the first and only of its kind — to prevent HIV, the creator of the drug, Gilead Sciences, announced on Wednesday.

Sold under the name Yeztugo, the company’s injectable HIV-1 capsid inhibitor (lenacapavir) reduces the risk of sexually acquired HIV in adults and adolescents.

“This is a historic day in the decades-long fight against HIV,” said Daniel O’Day, chairman and CEO of California-based Gilead Sciences, in a press release.

ALZHEIMER’S DISEASE COULD BE PREVENTED BY ANTIVIRAL DRUG ALREADY ON MARKET

The medicine, which only needs to be administered twice a year, has shown “remarkable outcomes in clinical studies,” as Gilead claims it could transform HIV prevention.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has approved a new, twice-yearly shot, Yeztugo, to prevent HIV, the creator of the drug announced on Wednesday. (Gilead Sciences via AP)

The drug is given as an injectable under the skin that the body then slowly absorbs. Individuals must have a negative HIV-1 test prior to starting the treatment.

In large trials last year, the drug was not only nearly 100% effective in its prevention of HIV, but proved superior to once-daily oral medication like Truvada, another drug by Gilead.

The drug is given as an injectable under the skin that the body then slowly absorbs. Individuals must have a negative HIV-1 test prior to starting the treatment. (AP Photo/Nardus Engelbrecht)

The journal Science named lenacapavir its 2024 “Breakthrough of the Year.”

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP FOR OUR HEALTH NEWSLETTER

Lenacapavir uses a multi-stage approach that distinguishes it from other approved antiviral medications.

Sold under the name Yeztugo, the company’s injectable HIV-1 capsid inhibitor (lenacapavir) reduces the risk of sexually acquired HIV in adults and adolescents. (iStock)

“While most antivirals act on just one stage of viral replication, lenacapavir is designed to inhibit HIV at multiple stages of its lifecycle,” states the press release from Gilead.

For more Health articles, visit www.foxnews.com/health

“Yeztugo is one of the most important scientific breakthroughs of our time and offers a very real opportunity to help end the HIV epidemic,” O’Day said in the press release.

The most commonly reported adverse reactions during clinical trials included injection site reactions, headache and nausea, according to the company.

-

Business1 week ago

Business1 week agoYale’s Endowment Selling Private Equity Stakes as Trump Targets Ivies

-

Culture1 week ago

Culture1 week agoBarbara Holdridge, Whose Record Label Foretold Audiobooks, Dies at 95

-

Culture1 week ago

Culture1 week agoA Murdered Journalist’s Unfinished Book About the Amazon Gets Completed and Published

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoYosemite Bans Large Flags From El Capitan, Criminalizing Protests

-

Education1 week ago

Education1 week agoWhat Happens to Harvard if Trump Successfully Bars Its International Students?

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoFox News Politics Newsletter: Hillary ‘Can’t Handle the Ratio'

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoTrumps to Attend ‘Les Misérables’ at Kennedy Center

-

Arizona1 day ago

Arizona1 day agoSuspect in Arizona Rangers' death killed by Missouri troopers