Finance

State aims to reclaim $850K from campaign finance vendor

OKLAHOMA CITY (KFOR) — The state is now looking to recoup around $850,000 from a company they said didn’t meet deadlines to create a campaign finance website.

It’s The Guardian and was supposed to be up and running in October, but that didn’t happen. The Guardian is the name of the state’s online campaign finance reporting system.

“They were unable to deliver a compliant system,” said Ethics Commission Executive Director Leeanne Bruce Boone during their meeting on Friday.

The company at the center of it all is RFD and Associates, based in Austin, Texas. They were hired in December 2024 to begin the project of creating The Guardian 2.0.

The previous company, according to the commission, was with Civix. However, problems arose between the state and that company, so they had to shift and find a new vendor.

The commission appropriated around $2.2 million for the endeavor.

Months went by, and according to the commission’s timeline, deadlines were missed altogether.

Dates in June were missed, and in August, the company received a warning from the Ethics Commission. The Office of Management and Enterprise Services (OMES) had to get involved in October and conduct an independent technical assessment.

The October date was proposed by the company, but it wasn’t met. In November, a formal notice of system failures and vendor non-compliance was noted.

“None of the milestones were met,” said Bruce Boone during the meeting. “Extensive corrective steps over many months. Written warnings were sent.”

At the Friday meeting, the commission voted to cut the contract with the company, and a contract with the previous one was then sent out.

“Terminate the contract and proceed with legal action,” said Bruce Boone.

Bruce Boone said that in total $850,000 was actually spent throughout this process on RFD. The new contract with Civix, she said, is estimated to cost over $230,000 and should last for three years. The effort is needed ahead of the 2026 election.

Now the commission has decided to bring in the Attorney General’s Office to see if they can get the money back.

“I take very seriously my role to ensure that taxpayer dollars are spent fairly and appropriately,” AG Drummond said in a statement. “My office stands ready to take legal action to recover damages, hold those responsible accountable, and work with the Ethics Commission to ensure the public has a reliable means to access campaign finance reports.”

News 4 attempted to get a statement out of the Chief Operating Officer of RFD and Associates, who had been in the meeting but quickly left after the commission voted.

“No comment,” said COO Scott Glover.

What would you say to taxpayers about that?

In response, he said, “I don’t agree with the ethics commission’s decision. That’s all I have to say.”

The Guardian had been delayed by several months, but the commission did respond appropriately and timely manner to requests made for documents.

The Guardian was back online Friday afternoon.

Suggest a Correction

Finance

Where in California are people feeling the most financial distress?

Inland California’s relative affordability cannot always relieve financial stress.

My spreadsheet reviewed a WalletHub ranking of financial distress for the residents of 100 U.S. cities, including 17 in California. The analysis compared local credit scores, late bill payments, bankruptcy filings and online searches for debt or loans to quantify where individuals had the largest money challenges.

When California cities were divided into three geographic regions – Southern California, the Bay Area, and anything inland – the most challenges were often found far from the coast.

The average national ranking of the six inland cities was 39th worst for distress, the most troubled grade among the state’s slices.

Bakersfield received the inland region’s worst score, ranking No. 24 highest nationally for financial distress. That was followed by Sacramento (30th), San Bernardino (39th), Stockton (43rd), Fresno (45th), and Riverside (52nd).

Southern California’s seven cities overall fared better, with an average national ranking of 56th largest financial problems.

However, Los Angeles had the state’s ugliest grade, ranking fifth-worst nationally for monetary distress. Then came San Diego at 22nd-worst, then Long Beach (48th), Irvine (70th), Anaheim (71st), Santa Ana (85th), and Chula Vista (89th).

Monetary challenges were limited in the Bay Area. Its four cities average rank was 69th worst nationally.

San Jose had the region’s most distressed finances, with a No. 50 worst ranking. That was followed by Oakland (69th), San Francisco (72nd), and Fremont (83rd).

The results remind us that inland California’s affordability – it’s home to the state’s cheapest housing, for example – doesn’t fully compensate for wages that typically decline the farther one works from the Pacific Ocean.

A peek inside the scorecard’s grades shows where trouble exists within California.

Credit scores were the lowest inland, with little difference elsewhere. Late payments were also more common inland. Tardy bills were most difficult to find in Northern California.

Bankruptcy problems also were bubbling inland, but grew the slowest in Southern California. And worrisome online searches were more frequent inland, while varying only slightly closer to the Pacific.

Note: Across the state’s 17 cities in the study, the No. 53 average rank is a middle-of-the-pack grade on the 100-city national scale for monetary woes.

Jonathan Lansner is the business columnist for the Southern California News Group. He can be reached at jlansner@scng.com

Finance

Why Chime Financial Stock Surged Nearly 14% Higher Today | The Motley Fool

The up-and-coming fintech scored a pair of fourth-quarter beats.

Diversified fintech Chime Financial (CHYM +12.88%) was playing a satisfying tune to investors on Thursday. The company’s stock flew almost 14% higher that trading session, thanks mostly to a fourth quarter that featured notably higher-than-expected revenue guidance.

Sweet music

Chime published its fourth-quarter and full-year 2025 results just after market close on Wednesday. For the former period, the company’s revenue was $596 million, bettering the same quarter of 2024 by 25%. The company’s strongest revenue stream, payments, rose 17% to $396 million. Its take from platform-related activity rose more precipitously, advancing 47% to $200 million.

Image source: Getty Images.

Meanwhile, Chime’s net loss under generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP) more than doubled. It was $45 million, or $0.12 per share, compared with a fourth-quarter 2024 deficit of $19.6 million.

On average, analysts tracking the stock were modeling revenue below $578 million and a deeper bottom-line loss of $0.20 per share.

In its earnings release, Chime pointed to the take-up of its Chime Card as a particular catalyst for growth. Regarding the product, the company said, “Among new member cohorts, over half are adopting Chime Card, and those members are putting over 70% of their Chime spend on the product, which earns materially higher take rates compared to debit.”

Today’s Change

(12.88%) $2.72

Current Price

$23.83 Market Cap

$7.9B

Day’s Range

$22.30 – $24.63

52wk Range $16.17 – $44.94

Volume

562K

Avg Vol

3.3M Gross Margin

86.34%

Key Data Points

Double-digit growth expected

Chime management proffered revenue and non-GAAP (adjusted) earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization (EBITDA) guidance for full-year 2026. The company expects to post a top line of $627 million to $637 million, which would represent at least 21% growth over the 2024 result. Adjusted EBITDA should be $380 million to $400 million. No net income forecasts were provided in the earnings release.

It isn’t easy to find a niche in the financial industry, which is crowded with companies offering every imaginable type of service to clients. Yet Chime seems to be achieving that, as the Chime Card is clearly a hit among the company’s target demographic of clientele underserved by mainstream banks. This growth stock is definitely worth considering as a buy.

Finance

How young athletes are learning to manage money from name, image, likeness deals

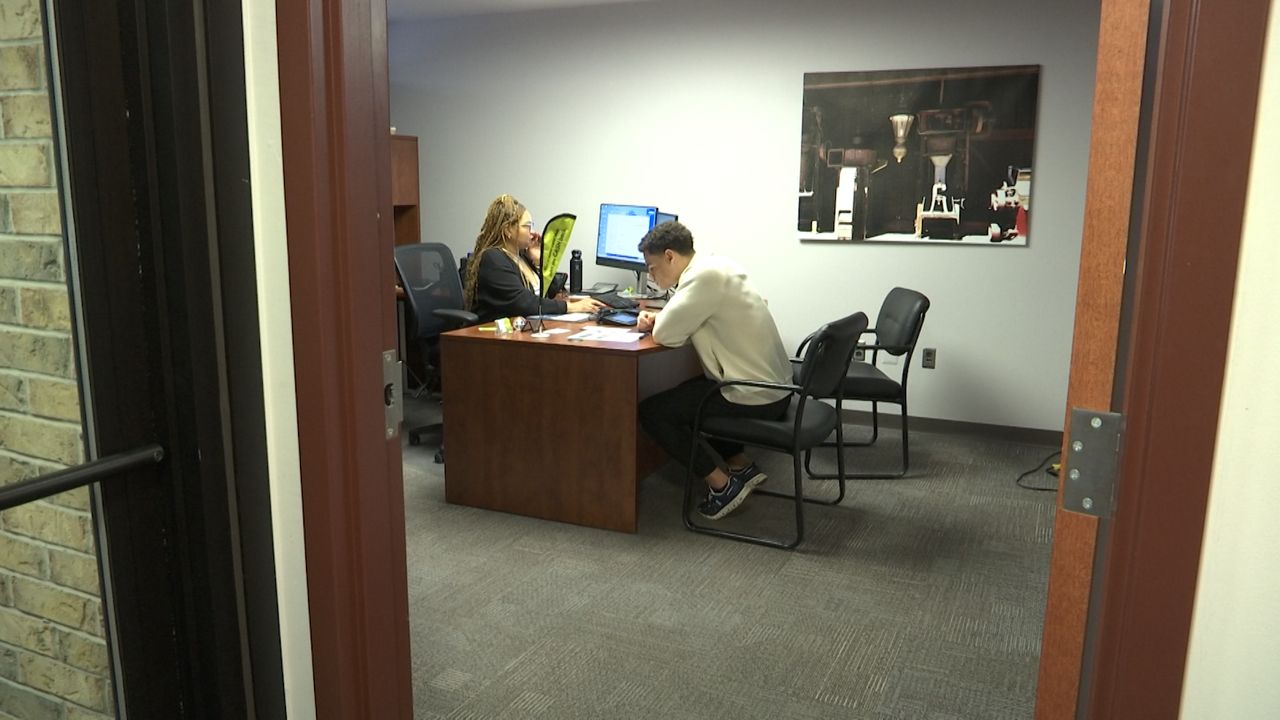

ROCHESTER, N.Y. — Student athletes are now earning real money thanks to name, image, likeness deals — but with that opportunity comes the need for financial preparation.

Noah Collins Howard and Dayshawn Preston are two high school juniors with Division I offers on the table. Both are chasing their dreams on the field, and both are navigating something brand new off of it — their finances.

“When it comes to NIL, some people just want the money, and they just spend it immediately. Well, you’ve got to know how to take care of your money. And again, you need to know how to grow it because you don’t want to just spend it,” said Collins Howard.

Preston said the experience has already been eye-opening.

“It’s very important. Especially my first time having my own card and bank account — so that’s super exciting,” Preston said.

For many young athletes, the money comes before the knowledge. That’s where Glory2Glory Sports Agency in Rochester comes in — helping athletes prepare for life outside of sports.

“College sports is now pro sports. These kids are going from one extreme to the other financially, and it’s important for them to have the tools necessary to navigate that massive shift,” said Antoine Hyman, CEO of Glory2Glory Sports Agency.

Through their Students for Change program, athletes get access to student checking accounts, financial literacy courses and credit-building tools — all through a partnership with Advantage Federal Credit Union.

“It’s never too early to start. We have youth accounts, student checking accounts — they were all designed specifically for students and the youth,” said Diane Miller, VP of marketing and PR at Advantage Federal Credit Union.

The goal goes beyond what’s in their pocket today. It’s about building habits that will protect them for life.

“If you don’t start young, you’re always catching up. The younger you start them, the better off they’re going to be on that financial path,” added Nihada Donohew, executive vice president of Advantage Federal Credit Union.

For these athletes, having the right support system makes all the difference.

“It’s really great to have a support system around you. Help you get local deals with the local shops,” Preston added.

Collins-Howard said the program has given him a broader perspective beyond just the game.

“It gives me a better understanding of how to take care of myself and prepare myself for the future of giving back to the community,” Collins-Howard said.

“These high school kids need someone to legitimately advocate their skills, their character and help them pick the right space. Everything has changed now,” Hyman added.

NIL opened the door. Programs like this one make sure these athletes walk through it — with a plan.

-

World2 days ago

World2 days agoExclusive: DeepSeek withholds latest AI model from US chipmakers including Nvidia, sources say

-

Massachusetts2 days ago

Massachusetts2 days agoMother and daughter injured in Taunton house explosion

-

Montana1 week ago

Montana1 week ago2026 MHSA Montana Wrestling State Championship Brackets And Results – FloWrestling

-

Oklahoma1 week ago

Oklahoma1 week agoWildfires rage in Oklahoma as thousands urged to evacuate a small city

-

Louisiana5 days ago

Louisiana5 days agoWildfire near Gum Swamp Road in Livingston Parish now under control; more than 200 acres burned

-

Denver, CO2 days ago

Denver, CO2 days ago10 acres charred, 5 injured in Thornton grass fire, evacuation orders lifted

-

Technology6 days ago

Technology6 days agoYouTube TV billing scam emails are hitting inboxes

-

Technology6 days ago

Technology6 days agoStellantis is in a crisis of its own making