CNN

—

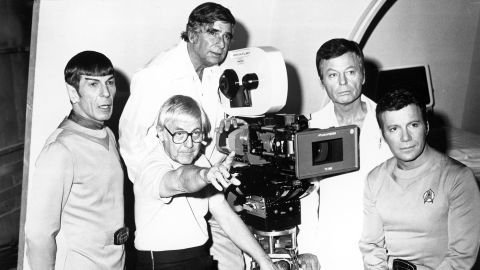

Rod Roddenberry Jr. is the one son of “Star Trek’s” iconic creator, however he by no means watched the present rising up. He was extra into vehicles, heavy steel music and watching motion tv exhibits like “Starsky & Hutch” and “Knight Rider.”

“It wasn’t till I received older and extra mature that I started to understand the depth and the mental aspect of ‘Star Trek,’” says Roddenberry, who was 17 when his father, Gene, died.

Years later, Roddenberry had a Trekkie conversion expertise. He began watching reruns and speaking to followers who advised tales of the present serving to them develop extra religion in humanity. That’s when he began to understand his father’s optimistic imaginative and prescient of a future the place individuals realized to thrill in variations and “inclusivity and equality are the norm.”

Roddenberry is now all aboard “Star Trek: Unusual New Worlds,” which premieres Could 5 on Paramount+. A prequel to the unique collection that aired within the Sixties, it’s primarily based on the years that Capt. Christopher Pike, a fan favourite who appeared within the unique collection, led the USS Enterprise.

The brand new present, one in all many “Star Trek” spinoffs, has been billed as a return to the optimism and romanticism of the unique collection, which ran from 1966-69.

Such a idealistic worldview could also be a tricky promote to right now’s audiences, battered by hateful politics, violence, conflict and dire warnings a few quickly warming planet. Nevertheless it’s a change that Roddenberry, an government producer with the brand new present, applauds.

“Saying nothing unhealthy in regards to the different exhibits, however that is the one I’m most enthusiastic about,” says Roddenberry, CEO of Roddenberry Leisure, which develops sci-fi graphic novels, podcasts, tv and movie initiatives.

“It’s going to return to the formatting of the unique collection. It’s the form of factor we have to get on the market to present us hope,” he provides. “I perceive that that is only a TV present, however it evokes numerous individuals to stay higher lives.”

Akiva Goldsman, the present’s government producer, says the brand new collection can be totally different and but the identical. Followers ought to anticipate extra stand-alone episodes, extra of the unique collection’ optimism and mind-bending twists paying homage to “The Twilight Zone.”

One other wrinkle is the brand new present’s concentrate on a few of “Star Trek’s” iconic characters. The present will study the evolution of such characters as Spock and Uhura earlier than they turned mythic figures, Goldsman says.

“Our Uhura is younger. She begins off as a cadet,” Goldsman says. “The place does she come from? What choices did she make to permit her to be in Starfleet and develop into the heroine we all know her to be?”

One other massive change is within the captain’s chair. The character of Captain Pike is way totally different than Kirk, Goldsman says.

“Jim Kirk is a younger boy’s fantasy of a ‘Star Trek’ captain,” Goldsman says. “He’s brash, impulsive – he is aware of the principles however doesn’t observe them. He’s a swashbuckler. Pike is a considerate man of cause who builds consensus.”

There are numerous debates within the Trekkie universe about what tv model of “Star Trek” is healthier, and whether or not subsequent collection departed an excessive amount of from the optimistic tone of the unique. That optimism is mirrored within the voiceover monologue by Captain Kirk at the start of every episode. He says the aim of the Enterprise is to “search out new life and journey,” and “discover unusual new worlds” – to not conquer civilizations or pressure inhabitants to simply accept sure beliefs.

In contrast, subsequent variations of the present, like “Star Trek: Deep House 9,” featured some characters who had been morally compromised or generally made choices that contradicted their values.

Ben Robinson, co-author of “Star Trek – The Authentic Collection: A Celebration,” says he hopes {that a} return to the franchise’s “unique recipe” will protect the hopefulness of the primary collection whereas providing advanced, characters with ethical struggles.

“I’m on the lookout for the unique collection, with a twenty first century finances,” Robinson says. “If they’ll mix subtle tales with stunning particular results and the Sixties ‘Proper Stuff’ energetic storytelling, then I’m going to be over the moon.”

One of many unspoken questions within the new collection is one you received’t see on lots of the present’s dialogue boards: Will Star Trek’s optimism and emphasis on inclusivity really feel outdated in right now’s cynical world?

It’s exhausting to place confidence in humanity by taking a look at information headlines. Racial, ethnic and political divisions appear as deep because the outer reaches of house itself.

Then once more, feel-good, inclusive TV collection equivalent to “Schitt’s Creek” and “Ted Lasso” discovered big audiences within the pandemic, a development many attribute to audiences being starved for hopeful tales.

“Darkish instances require hopeful storytelling,” says Goldsman. “Optimism and perception in a greater future is critical for lots of us.”

Goldsman says it’s a fantasy that the unique “Star Trek” aired in an gentler period that was a lot totally different than ours. He cites 1968 for instance.

“We had been at conflict,” he says of the US’s involvement in Vietnam. “The civil rights motion was nonetheless in its personal intense second of battle. Bobby Kennedy and Martin Luther King Jr. had been killed, to not point out the looming nuclear menace. The nation was fairly factionalized. The ’60s had been a tumultuous time.”

“Star Trek’s” futuristic world allowed it to handle among the most explosive problems with that period in a approach that no different present might, says Robinson, the creator. The composition of the Enterprise crew was itself a name for tolerance, he says.

Contemplate: The US was embroiled in a chilly conflict with the Soviet Union, however one of many Enterprise’s foremost officers was Russian (Chekov). The nation had solely 20 years earlier ended a brutal conflict with Japan, however the ship’s helmsman was Japanese (Sulu). Black individuals couldn’t vote in lots of elements of the nation, however a Black officer – and a girl – (Uhura) was the ship’s communications officer.

Spock was the final word mannequin minority on the Enterprise. He was an outsider who endured prejudice. Black and biracial individuals recognized with him (there’s a stupendous story in regards to the actor Leonard Nimoy writing a letter to a biracial lady who felt rejected). One Star Trek fan referred to as him the “Blackest individual on the Enterprise” as a result of he “by no means let ‘the person” see his emotion and “was cool like one of the best jazz musicians.”

“It’s metaphorical storytelling that enables you a approach of taking science and fantasy to have a look at your personal society,” Robinson says. “He [Roddenberry Sr.] talked about race by having a Vulcan as an alternative of a Black man.”

It’s a minor miracle that Star Trek’s creator was so hopeful about humanity. He noticed and skilled a lot tragedy throughout his lifetime. Roddenberry Sr. was born in El Paso, Texas, and virtually died as a toddler when his home caught hearth. A passing milkman rescued him.

He had extra shut calls as an grownup. He was a pilot for the US Military Air Corps who flew fight missions within the South Pacific throughout World Warfare II. And he was a crew member of a Pan Am flight that crash-landed within the Syrian desert, killing 14 individuals. A later stint as an officer with the Los Angeles Police Division uncovered him to the seamier aspect of life.

And but regardless of all that, Roddenberry imagined a compassionate and harmonious future world that was a lot totally different from the one he lived in.

How can somebody who’d seen a lot tragedy be so optimistic?

Robinson, the creator, pointed to a quote from musician John Lennon.

“Lennon stated the explanation I’m going on about peace and love a lot is as a result of I’m actually offended,” he says. “Possibly you search for what you want for your self. Gene was a troubled soul for certain.”

Roddenberry transformed his ache right into a imaginative and prescient of the long run that also evokes thousands and thousands greater than 50 years later. Phrases equivalent to “Dwell lengthy and prosper,” “Beam me up, Scotty” and “warp drive” are actually a part of fashionable tradition.

And so is “Star Trek’s” humane message, which lives on within the new present.

“If individuals say, ‘Why is ‘Star Trek’ nonetheless round?’, I’ll let you know why,” Roddenberry Jr. says. “It’s as a result of it’s the thought of appreciating the entire issues which are totally different and never simply tolerating them, and that it’s the variations that we’re going to develop from.”

The response to “Star Trek: Unusual New Worlds” will reveal whether or not that imaginative and prescient nonetheless resonates with individuals, or whether or not the obstacles of cynicism and hate are actually too excessive for even the USS Enterprise to steer via.