Entertainment

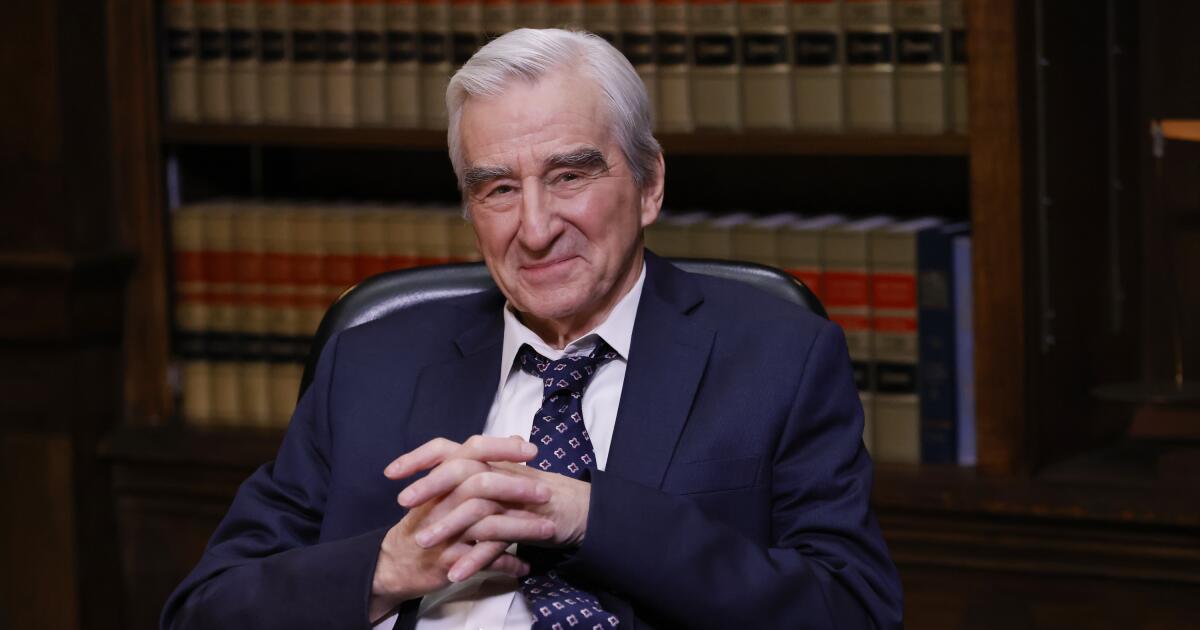

Sam Waterston talks about his final 'Law & Order' episode and Jack McCoy's 'beautiful exit'

“It’s been a hell of a ride.”

With those parting words, Jack McCoy stepped down from his job as Manhattan district attorney after decades of public service — and Sam Waterston bid farewell to his signature role on “Law & Order” after 19 seasons and 405 episodes spread over 30 years.

To put this run into perspective, Waterston made his debut appearance as McCoy in September 1994 in the Season 5 premiere of “Law & Order” — the same week that “ER” and “Friends” premiered on NBC. The Dick Wolf procedural — which famously told stories about “the police who investigate crime and the district attorneys who prosecute the offenders” was already a well-established hit, but it had yet to become a ubiquitous, seemingly indestructible pop culture franchise.

Waterston, who joined the series after the contentious departure of actor Michael Moriarty, helped prove that the format was durable enough to withstand major cast shakeups. Yet he also became the closest thing “Law & Order” had to a central protagonist — the “ultimate conscience of the show,” as Wolf has put it.

Well before male antiheroes took over TV, Waterston played McCoy as a no-nonsense attorney who was passionate about justice but also willing to bend the rules in order to obtain a conviction — a prickly character whose sharp edges were somehow softened by Waterston’s soothing voice and avuncular demeanor. And though McCoy’s personal life was hinted at only fleetingly throughout the series, the character clearly wrestled with private demons (including a proclivity for affairs with his glamorous assistant district attorneys).

A Yale-educated actor who has played Hamlet on Broadway, Waterston admits there was a time he looked down on TV. Initially, he only planned to do a single season of “Law & Order.” But Waterston remained on the series until it was canceled in 2010. He is the rare actor to star in a long-running TV series who managed not to be pigeonholed by the part that made him famous, working continually in the dozen years “Law & Order” was off the air in shows including “Grace and Frankie.” He agreed to reprise his role when NBC revived the series in 2022, anchoring a new cast that included Hugh Dancy as assistant district attorney Nolan Price. But earlier this month, NBC announced that Waterston would be leaving the series, with Tony Goldwyn set to star as the incoming D.A.

Waterston’s farewell episode — written by Rick Eid and Pamela Wechsler and fittingly titled “Last Dance” — follows the case of Scott Kelton (Rob Benedict), a billionaire tech mogul who is accused of murdering a young woman in Central Park. Mayor Robert Payne (Bruce Altman), whose son is implicated in the case, pushes the D.A.’s office to cut a deal with Kelton — or else he’ll support McCoy’s opponent in the coming election. McCoy resists the pressure and decides to try the case himself, urging the jury to rule fairly and without prejudice despite the high-profile defendant. It works: Kelton is convicted. Over a celebratory drink with Price, he announces he’s going to retire so that the governor can appoint “someone with integrity” to the job. In the closing shot of the episode, McCoy stands alone at night outside the Supreme Court building in Lower Manhattan — then walks off into the darkness.

The Times recently spoke via Zoom with Waterston, who will play Franklin Roosevelt in Tyler Perry’s upcoming World War II drama “Six Triple Eight.” At 83, he is eager to tread the boards once again — and to continue working as steadily as he has for the last six decades.

“Actors don’t really get to tell the future,” he said. “But I’m open for business. If anybody’s reading this and thinking, ‘Oh, too bad. He retired.’ I haven’t retired.”

Jill Hennessy, left, and Sam Waterston in a 1995 episode of “Law & Order.”

(Jessica Burnstein / NBC)

Let’s start with the obvious: Why did you decided to leave now?

I always knew that I was going to stay on a short time. I didn’t want to turn on the TV and see somebody else playing the part when the show came back [in 2022] but I knew it was not for the long term. This was always going to be the year [to leave]. And then “Law & Order” designed just a beautiful exit. I couldn’t have been more pleased with it. They gave me this fantastic send-off, with a pop-up delicatessen on the set, called Sam’s Delicatessen. The last shots were all in the courtroom and speeches were made. Dick Wolf showed up. It was something else.

What did you make of McCoy’s decision to step down rather than face likely defeat in an election?

Once he found out that Sam Waterston was leaving, it was pretty much a done deal.

Take me back to 1994, when you were cast on the show. What made the role appealing to you?

Dick Wolf took me out to lunch and persuaded me that it was a really good idea. Ed Sherin was the executive producer in New York, and he set the tone and made it a really interesting place to work. He was a theater director, and he did a lot of work in television. He had the dream of a lifetime to set up a resident theater somewhere, but he said that this was the fulfillment of that dream. And he grew talent, staff, sound guys, focus pullers — people that are now directors out in the world because of him. It was an extraordinary place to be. It was easy to stay, but I always thought I was gonna leave the next year. I kept on signing up for one more season.

It was known for drawing many actors from New York theater.

We used to joke that it was the Café de la Paix of television. You know that saying about the Café de la Paix, “If you sit there long enough, the whole world passes by?” We used to joke, that was what went on [at “Law & Order”]. We had fantastic guest stars, and all kinds of people who then grew up to be stars on their own. Don’t ask me to name them.

One of the things that’s interesting about “Law & Order” is that we never learn much about the characters outside of work. Jack McCoy’s backstory is pretty patchy, even after 19 seasons. Does this present any challenges — or rewards — to you as a performer?

The reward is that your own life is not used up. A lot of what you can do and what you are as an actor is also not used up. That means that if somebody goes to see you in a play or a movie while you’re doing “Law & Order,” the audience doesn’t think, “Oh, gee, I already saw this.” And the stuff that you do get to do on the show, and in the case of [when I was] playing McCoy, was very intense, very engaging. The quality control at Wolf Films is fantastically high, so it was good stuff.

Do you have a favorite scene or episode from your run on the series?

The episode that hit me the hardest didn’t really have to do with me, it had to do with Steven Hill, who was playing the D.A. [Adam Schiff] in those days. We did a death penalty [storyline in which] his wife was on life support and dying. He was against pursuing the death penalty [in a case], but the state of New York was for it. [In the episode, “Terminal,”] they juxtaposed the execution, which Jack and his assistant witnessed, with Steven Hill sitting at his wife’s bedside as she was taken off of life support. It was unforgettable. It wasn’t just great “Law & Order,” it was great TV and not just great TV, but really, really mighty.

How do you think Jack McCoy evolved over the years? Especially in earlier seasons, he was known for doing whatever it took to get a conviction. Did he mellow with age?

I don’t think he changed. I think being the D.A. was hard on him because he didn’t change, but to do what was necessary to do the job, he had to restrain himself in ways that he didn’t have to before.

You came back to the show after 12 years away. Was that strange?

What was strange was how familiar it was. What was really strange was that our set, for the whole time that I was on the show, had been at Chelsea Piers, on the west side of Manhattan and they rebuilt those sets at a studio in Queens. You walked onto the set and you’re back in the same world. It made the hair stand up on the back of your neck. When I did “The Great Gatsby,” I walked out of a door in Newport, R.I., and walked into a room in London. That was creepy too.

You did plenty of TV before “Law & Order,” including the NBC drama “I’ll Fly Away,” but you were primarily known for movies and theater. Did you look down on TV at the time?

Of course I did. We all had the same prejudices and now, lo and behold, streaming services are the business. We looked down on it, and we were stupid. When I was growing up, theater was the thing. And the movies were looked down upon. How unbelievable is that? We were dumb people.

You have played Abraham Lincoln on numerous occasions (including in the miniseries “Lincoln” and as a voice actor in Ken Burns’ “The Civil War”), What keeps drawing you back to this part?

I always used to say that if you’re an actor, there should be some reward for being plain. I counted that as the reward. [laughs] It was an excuse to go down an endless rabbit hole of fascination with a really extraordinary person. You can’t exhaust the fascination, especially if you like words. I started out wanting to be a Shakespearean actor. That’s all I wanted. And Lincoln had a way with words.

Odelya Halevi, left, as Samantha Maroun, Hugh Dancy as Nolan Price and Sam Waterston in a scene from “Law & Order.”

(Eric Liebowitz / NBC)

I have to point out that you also played Robert Oppenheimer in a 1980 TV series called “Oppenheimer.”

If you live long enough, all the parts you’ve ever played in your life will come back to you being played by somebody else.

As you look ahead at your career, are there roles that you are still hoping to play?

Sure, but there is no planning. Bradley Cooper plans his career. I am not an actor-producer, so I am very much subject to what comes under the door. There are lots of things I want to do. Joel Gray and I want to do “On Borrowed Time,” a play that was made in 1938 and made into a movie starring Lionel Barrymore. I want to do that, but will I get to do it? We’ll see.

How have you been spending the spare time since you finished the show?

It is mind-boggling. There’s never been a time in all the 60 years of my working as an actor — for which I would like to take this opportunity to thank all the people reading this article, and everybody else in the world [who is] watching — there’s really been no time when I wasn’t either working, or really sweating looking for work. This is the first time I’ve walked off a set without thinking, “What the hell am I going to do next?” It was literally a physical feeling that there was a space opening up in my head that I had not even known existed for all those years, space that was taken up by the job or the search for the job. Suddenly you’re free to think about all kinds of other things. It’s intoxicating and makes you feel drunk.

Fascinating. Is it the freedom of not having to learn all those lines?

That’s part of it. “I have these lines, will I know them on the day?” Also, for an actor, it’s got to do with having a piece of your mind occupied by somebody other than yourself — by the character. I haven’t retired, but McCoy has. I don’t know where he is. He’s on a beach in Brazil or something. But he’s not in my head and it’s really quite extraordinary and wonderful. Just wonderful! But I loved [playing McCoy]. Boy, what a blessing.

You and Jerry Orbach were named living landmarks in New York City. Do you have any recollections of working with him, even though you were not often in scenes together?

We weren’t in that many scenes. But we did pass each other in the hall in the studio very often. And he’s one of the most extraordinary and beautiful people I have ever known, certainly in the profession. I broke one of his rules, which was that you never leave a show while it’s running. I’m going around, saying this to anybody who will listen, that I hope that the theater gods won’t punish me for breaking his rules.

Do you ever find yourself in a hotel room or on a plane, watching yourself in old episodes of “Law & Order” and getting sucked in?

My wife likes to watch old episodes of “Law & Order” while she’s cooking. Sometimes I’m passing through the kitchen and I stop and I think, “Why were you so critical of how you looked in those days? Look at yourself now.”

Movie Reviews

MOVIE REVIEWS: “Mercy,” “Return to Silent Hill,” “Sentimental Value” & “In Cold Light” – Valdosta Daily Times

“Mercy”

(Thriller/Crime: 1 hour, 39 minutes)

Starring: Chris Pratt, Rebecca Ferguson, Kali Reis

Director: Timur Bekmambetov

Rated: PG-13 (Violence, bloody images, strong language, drug content and teen smoking)

Movie Review:

“Mercy” is a science fiction movie based on one of the more common themes of moviedom lately, artificial intelligence (AI). This crime thriller cleverly creates an intriguing story using technology and the justice system, yet it fails to be consistently interesting and intelligent throughout. The conclusion is less significant than the initial setup, as the concluding scenes become typical action sequences.

Detective Chris Raven (Pratt) of the LA Police Department is a huge supporter of the city’s new judicial courtroom. Crimes are now judged by an AI program (Ferguson) in the Mercy Court. The court is run by an artificial program that makes decisions based on all of the evidence before it without any prejudice. Detective Raven is all for this system until he is convicted of killing his wife. Now he must use all of the data, including the AI‘s ability to tap into everyone’s electronic devices, security cameras, and even into government files, within reason, to prove he did not murder his wife.

Mercy is an interesting movie. It entertains throughout, even when the story gets sloppy and characters’ actions are irrational. This mainly occurs during the final scenes. The movie tries too hard to insert unneeded narrative twists. This is disappointing because the story is interesting. What makes it fascinating is that it happens in real time. This is the most brilliant facet.

All the other theatrics are unnecessary. Director Timur Bekmambetov (“Profile,” 2018; “Wanted,” 2008) and “Mercy’s” producers should have just kept the ending simple, no plot twists or superfluous action sequences.

Grade: C (This flick needs some mercy. Let the trial begin.)

“Return to Silent Hill”

(Horror: 1 hour, 46 minutes)

Starring: Jeremy Irvine, Hannah Emily Anderson and Robert Strange

Director: Christophe Gans

Rated: R (Bloody violent content, strong language and brief drug use.)

Movie Review:

“Return to Silent Hill” is about one man’s quest to return to the love of his life. The problem is she has moved on to the afterlife. Meanwhile, audiences lose part of their life watching this movie, which is unlike any of the two prequels in this series. This one is a psychological horror that bores.

Artist James Sunderland (Irvine) decides to return to Silent Hill, a place where many people died during a devastating illness that nearly enveloped the entirety of the city’s population. What is left there is a horror show of freakish creatures, all with violent intent. Still, Sunderland searches for the love of his life, Mary Crane (Anderson).

Think of this movie as a slow suicide, where a guy goes back to retrieve his dead girlfriend. To do so, he must travel to the modern land of the dead that Silent Hill has become. This one is a type of swan song by the main character, and the movie becomes less scary while lackluster romantic notions wander aimlessly.

Grade: D (Do not return to see this.)

“Sentimental Value”

(Drama: 2 hours, 13 minutes)

Starring: Renate Reinsve, Stellan Skarsgård, Inga Ibsdotter Lilleaas and Elle Fanning

Director: Joachim Trier

Rated: R (Language, sexual reference, nudity and thematic elements)

Movie Review:

“Sentimental Value” is a Norwegian film that won the Grand Prix in France’s Cannes Film Festival and was nominated for nine Academy Awards, including Best Motion Picture. It is a solid drama filled with symbolism and family connections. It is brilliant performances by a talented cast under the direction of Joachim Trier (“The Worst Person in the World,” 2021).

This screenplay is about Gustav Borg (Skarsgård). He is a father, grandfather and a famed film director. He stayed away from his two daughters, actress Nora Borgwhile (Reinsve) and historian Agnes Borg Pettersen (Lilleaas), while he was creating works as a filmmaker. The director comes back into the lives of his daughters after the death of their mother. Their reunion leads to a rediscovery of their bond at their family home in Oslo.

Stellan Skarsgård is always a solid actor. He takes his roles and makes them tangible characters that seem like you know them, even when they’re speaking a foreign language. That is the quality of his act and why he gets nominated for multiple awards each season.

“Sentimental Value” is a valuable movie filled with enriching sentiment. It is an enjoyable film for those who value a good drama. The acting and original writing alone make the movie worth it. “Sentimental Value” starts in a very simple way, but everything in between, even when low-key, remains potent. Joachim Trier and writer Eskil Vogt have worked together on multiple projects such as “The Worst Person in the World” (2021). Their pairing is once again worthy.

Grade: A- (Any motive valuable movie.)

“In Cold Light ”

(Crime: 1 hour , 36 minutes)

Starring: Maika Monroe, Allan Hawco and Troy Kotsur

Director: Maxime Giroux

Rated: R (Violence, bloody images, strong language and drug material)

Movie Review:

“In Cold Light” sticks to a very straightforward story, primarily taking place over a short period. The problem is the story leaves one in the cold. Audiences have to guess what is being communicated because this movie uses American Sign Language (ASL) without subtitles. For those moviegoers who do not know ASL, they are left deciphering characters’ actions and facial expressions during some pivotal scenes.

Ava Bly (Monroe) attempts to start a legit life after prison. Her life changes when Ava’s twin, Tom Bly (Jesse Irving) is murdered while seated next to her. As her brother’s killers pursue her, Ava must evade law enforcement, which contains some crooked cops led by Bob Whyte (Hawco).

For a brief moment, this movie hits its exceptional moment when Oscar-recipient Helen Hunt enters the picture as a motherly Claire, a crime boss who seems more like a social worker/psychologist. Her long scene is wasted as it arrives too late.

French Canadian director Maxime Giroux’s style has potential in his first English-language film, but it does not fit a wayward narrative. A rarity, this crime drama has characters commit many dumb actions at once.

Moreover, Giroux (“Félix et Meira,” 2014) and writer Patrick Whistler forget to let their audiences in on their story. They allow much to get lost in translation, especially during heated conversations between Monroe’s Ava and her father, Will Bly, played by Academy Award-winning actor Troy Kotsur (“CODA,” 2021).

Grade: C- (Just cold and dark.)

More movie reviews online at www.valdostadailytimes.com.

Entertainment

Paramount-Warner Bros. deal stirs fears about what it means for CNN

As the media industry took stock of Paramount Skydance’s startling acquisition of Warner Bros. Discovery, one question lingered on the minds of many in the news business and beyond: What will this mean for CNN?

The iconic 24-hour cable news network is among the various Warner Bros. assets that would be scooped up by Paramount in a deal announced Thursday that could transform the media landscape.

Paramount has undergone a swift transformation under Chief Executive David Ellison following his family’s acquisition of the company last summer. These changes reached CBS News almost immediately with the appointment of Bari Weiss, the controversial Free Press co-founder, as its new editor in chief.

Bari Weiss moderated a town hall with Erika Kirk, widow of slain conservative activist Charlie Kirk.

(CBS via Getty Images)

Weiss’ tenure so far has been rocky.

Her decision to pull a “60 Minutes” story about conditions inside an El Salvador prison that housed undocumented Venezuelan migrants from the U.S. received widespread criticism and accusations of political motivation. The network said the story was held for more reporting, and the segment eventually aired.

There was more upheaval last week at the news magazine, when “60 Minutes” correspondent and CNN news anchor Anderson Cooper announced that he’d be leaving to spend more time with his family.

And earlier this year, a veteran producer at “CBS Evening News With Tony Dokoupil” was fired after he expressed disagreement about the editorial direction of the newscast.

Now, the concern is that similar changes could be in store for CNN, which has long been a target of President Trump’s ire. He has personally called for the ouster of hosts at the network who have questioned his policies.

CNN Worldwide Chief Executive Mark Thompson tried to quell some of those fears, particularly inside his own newsroom.

In an internal memo dated Thursday and obtained by The Times, Thompson urged employees not to “jump to conclusions about the future” and try to concentrate on their work.

“We’re still near the start of what is already an incredibly newsy year at home and abroad,” he wrote in the note. “Let’s continue to focus on delivering the best possible journalism to the millions of people who rely on us all around the world.”

Chairman and CEO of CNN Worldwide Mark Thompson and media editor for Semafor, Maxwell Tani, speak onstage.

(Shannon Finney / Getty Images for Semafor)

CNN declined to comment beyond Thompson’s memo.

Ellison has said his vision for a news business is one that is ideologically down the middle.

“We want to build a scaled news service that is basically, fundamentally in the trust business, that is in the truth business, and that speaks to the 70% of Americans that are in the middle,” he said during a Dec. 8 interview on CNBC, shortly after Warner said it had chosen Netflix as the winning bidder for its studios, HBO and HBO Max. “And we believe that by doing so that is for us, kind of doing well, while doing good.”

Ellison demurred when asked whether Trump would embrace him as CNN’s owner, given the president’s past criticisms of the network.

“We’ve had great conversations with the president about this, but … I don’t want to speak for him in any way, shape or form,” he said.

First Amendment scholars have raised concerns about press freedom and free speech rights under the Trump administration, particularly after last month’s arrest of former CNN journalist Don Lemon and the Federal Communications Commission’s pressure on late-night hosts like Jimmy Kimmel and Stephen Colbert.

Press freedom groups have long asked questions in other countries about how authoritarian regimes use their power and “oligarchical alliances to belittle, silence, and punish independent journalistic voices, or to steer media ownership toward … a preferred version of the truth,” said RonNell Andersen Jones, a 1st Amendment scholar and distinguished professor in the college of law at the University of Utah, in an email.

“We see them asking at least some of these questions about the U.S. today,” she wrote.

Apprehension about the merger also extends beyond its implications for CNN and the media business.

Lawmakers such as Rep. Laura Friedman (D-Glendale), Sen. Adam Schiff (D-Calif.) and Sen. Cory Booker (D-N.J.) have raised concerns about how the consolidation of two major Hollywood studios could affect industry jobs and film and television production — which has significantly slowed since the pandemic, the dual writers’ and actors’ strikes in 2023 and corporate cutbacks in spending.

Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) called the deal an “antitrust disaster” that she feared could raise prices and limit choices for consumers.

“With the cloud of corruption looming over Trump’s Department of Justice, it’ll be up to the American people to speak up and state attorneys general to enforce the law,” she said in a statement.

Already, California Atty. Gen. Rob Bonta has said the merger isn’t a “done deal,” adding that he is in communication with other states attorneys general about the issue.

“As the epicenter of the entertainment industry, California has a special interest in protecting competition,” he posted Friday on X.

The deal is subject to approval by the U.S. Justice Department. Bonta and other state attorneys general are expected to file a legal challenge to the mega-merger on antitrust grounds.

Ellison addressed some of these concerns in a statement Friday.

“By bringing together these world-class studios, our complementary streaming platforms, and the extraordinary talent behind them, we will create even greater value for audiences, partners and shareholders,” he said. “We couldn’t be more excited for what’s ahead.”

Times staff writer Meg James contributed to this report.

Movie Reviews

Movie Review: ‘Goat’ – Catholic Review

NEW YORK (OSV News) – “Goat” (Sony) is an animated underdog sports comedy populated by anthropomorphized animals. While mostly inoffensive, and thus suitable for a wide audience — including teens and older kids — the film is also easily forgotten.

The amiable proceedings center on teen goat Will Harris (voice of Caleb McLaughlin). As opening scenes show, it has been Will’s dream since childhood to play for his hometown team, the Vineland Thorns.

The inhabitants of Vineland and the other areas of the movie’s world, however, are divided into so-called bigs and smalls, with professional competition dominated, unsurprisingly, by the former. Though Will stoutly maintains that he’s a medium, those around him regard him as too slight and diminutive to go up against the towering bigs.

Despite this prejudice, a video showing Will more or less holding his own against a famous and arrogant big, Andalusian horse Mane Attraction (voice of Aaron Pierre), goes viral and inspires the Thorns’ devious owner, warthog Flo Everson (voiced by Jenifer Lewis), to give the lad a shot. Though Will is understandably thrilled, his path forward proves challenging.

Will has idolized the Thorns’ sole outstanding player, black panther Jett Fillmore (voice of Gabrielle Union), since he was a youngster. But Jett, it turns out, is not only frustrated by her situation as a star among misfits but scornful of Will’s ambitions and resolute in helping to deprive her new teammate of playing time.

Given such divisions, the Thorns’ fortunes seem destined to continue their long decline.

“Roarball,” the invented game featured in director Tyree Dillihay’s film, is essentially co-ed basketball by another name. As produced by, among others, NBA champion Stephen Curry, the movie — adapted from an idea in Chris Tougas’ book “Funky Dunks” — is an unabashed celebration of hoop culture both on and off the court.

Viewers’ enthusiasm may vary, accordingly, depending on the degree to which they’re invested in the real-life sport.

Moviegoers of every stripe will appreciate the fact that the script, penned by Aaron Buchsbaum and Teddy Riley, shows the negative effects of self-centeredness as well as the value of teamwork and fan support. Plot developments also showcase forgiveness and reconciliation.

Will’s story is, nonetheless, thoroughly formulaic and most of the screenplay’s jokes feel strained and laborious. Still, while hardly qualifying as the Greatest of All Time, “Goat” does provide passable entertainment with little besides a few potty gags to concern parents.

The film contains brief scatological humor and at least one vaguely crass term. The OSV News classification is A-II — adults and adolescents. The Motion Picture Association rating is PG — parental guidance suggested. Some material may not be suitable for children.

Read More Movie & TV Reviews

Copyright © 2026 OSV News

-

World2 days ago

World2 days agoExclusive: DeepSeek withholds latest AI model from US chipmakers including Nvidia, sources say

-

Massachusetts3 days ago

Massachusetts3 days agoMother and daughter injured in Taunton house explosion

-

Montana1 week ago

Montana1 week ago2026 MHSA Montana Wrestling State Championship Brackets And Results – FloWrestling

-

Louisiana5 days ago

Louisiana5 days agoWildfire near Gum Swamp Road in Livingston Parish now under control; more than 200 acres burned

-

Denver, CO3 days ago

Denver, CO3 days ago10 acres charred, 5 injured in Thornton grass fire, evacuation orders lifted

-

Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoYouTube TV billing scam emails are hitting inboxes

-

Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoStellantis is in a crisis of its own making

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoOpenAI didn’t contact police despite employees flagging mass shooter’s concerning chatbot interactions: REPORT