Entertainment

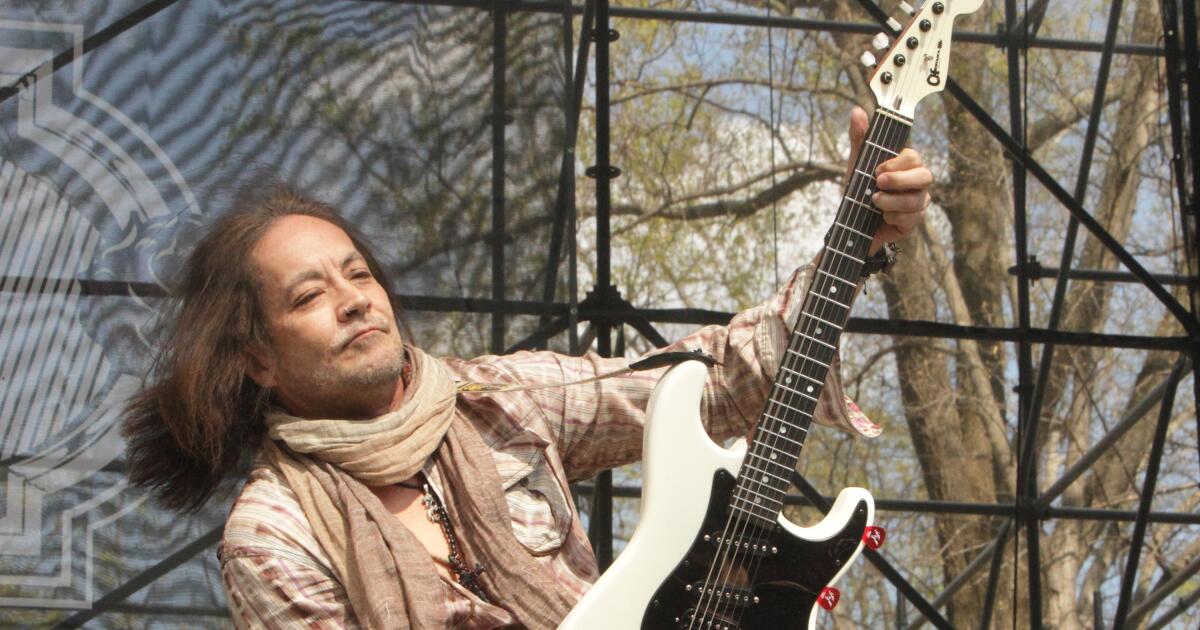

Rocker Jake E. Lee shot multiple times in Las Vegas, expected to fully recover, rep says

Guitarist Jake E. Lee, who has played with Ozzy Osbourne, Badlands, Cinderella and Red Dragon Cartel, was shot multiple times in Las Vegas on Tuesday, his spokesperson said.

The 67-year-old was shot early Tuesday but is “fully conscious and doing well in an intensive care unit at a Las Vegas hospital,” spokesperson Amanda Cagan said in a statement to The Times. “He is expected to fully recover.”

Cagan said Las Vegas authorities believe that the shooting was “completely random” and that it occurred while Lee was walking his dog.

“As the incident is under police investigation, no further comments will be forthcoming. Lee and his family appreciate respecting their privacy at this time,” Cagan said.

Officers from the Las Vegas Metropolitan Police Department responded to a shooting incident at 2:42 a.m. in the 11000 block of Alora Street, about 10 miles south of the Las Vegas Strip, the agency confirmed Tuesday in a statement to The Times. After officers arrived, they “located a male victim suffering from apparent gunshot wounds,” and he was transported to a hospital, the agency said.

No arrests have been made, and the investigation is ongoing, the department said.

Movie Reviews

Movie Review – SHAKA: A STORY OF ALOHA

Entertainment

Tommy Lee Jones’ daughter reportedly found dead at San Francisco hotel on New Year’s Day

Victoria Jones, the daughter of Academy Award-winning actor Tommy Lee Jones, was reportedly found dead at a hotel in San Francisco on New Year’s Day. She was 34.

According to TMZ, the San Francisco Fire Department responded to a medical emergency call at the Fairmont San Francisco early Thursday morning. The paramedics pronounced Victoria dead at the scene before turning it over to the San Francisco Police Department for further investigation, the outlet said.

An SFPD representative confirmed to The Times that officers responded to a call at approximately 3:14 a.m. Thursday regarding a report of a deceased person at the hotel and that they met with medics at the scene who declared an unnamed adult female dead.

Citing law enforcement sources, NBC Bay Area also reported that the deceased woman found in a hallway of the hotel was believed to be Jones and that police did not suspect foul play.

“We are deeply saddened by an incident that occurred at the hotel on January 1, 2026,” the Fairmont told NBC Bay Area in a statement. “Our heartfelt condolences are with the family and loved ones during this very difficult time. The hotel team is actively cooperating and supporting police authorities within the framework of the ongoing investigation.”

The medical examiner conducted an investigation at the scene, but Jones’ cause of death remains undetermined. Dispatch audio obtained by TMZ and People indicated that the 911 emergency call was for a suspected drug overdose.

Jones was the daughter of Tommy Lee and ex-wife Kimberlea Cloughley. Her brief acting career included roles on films such as “Men in Black II” (2002), which starred her father, and “The Three Burials of Melquiades Estrada” (2005), which was directed by her father. She also appeared in a 2005 episode of “One Tree Hill.”

Page Six reported that Jones had been arrested at least twice in 2025 in Napa County, including an arrest on suspicion of being under the influence of a controlled substance and drug possession.

Movie Reviews

Movie Review: “I Was a Stranger” and You Welcomed Me

Just when you think that you’ve seen and heard all sides of the human migration debate, and long after you fear that the cruel, the ignorant and the scapegoaters have won that shouting match, a film comes along and defies ignorance and prejudice by both embracing and upending the conventional “immigrant” narrative.

“I Was a Strranger” is the first great film of 2026. It’s cleverly written, carefully crafted and beautifully-acted with characters who humanize many facets of the “migration” and “illegal immigration” debate. The debut feature of writer-director Brandt Andersen, “Stranger” is emotional and logical, blunt and heroic. It challenges viewers to rethink their preconceptions and prejudices and the very definition of “heroic.”

The fact that this film — which takes its title from the Book of Matthew, chapter 25, verse 35 — is from the same faith-based film distributor that made millions by feeding the discredited human trafficking wish fulfillment fantasy “Sound of Freedom” to an eager conservative Christian audience makes this film something of a minor miracle in its own right.

But as Angel Studios has also urged churchgoers not just to animated Nativity stories (“The King of Kings”) and “David” musicals, but Christian resistence to fascism (“Truth & Treason” and “Bonheoffer”) , their atonement is almost complete.

Andersen deftly weaves five compact but saga-sized stories about immigrants escaping from civil-war-torn Syria into a sort of interwoven, overlapping “Babel” or “Crash” about migration.

“The Doctor” is about a Chicago hospital employee (Yasmine Al Massri of “Palestine 36” and TV’s “Quantico”) whose flashback takes us to the hospital in Aleppo, Syria, bombed and terrorized by the Assad regime’s forces, and what she and her tween daughter (Massa Daoud) went through to escape — from literally crawling out of a bombed building to dodging death at the border to the harrowing small boat voyage from Turkey to Greece.

“The Soldier” follows loyal Assad trooper Mustafa (Yahya Mahayni was John the Baptist in Martin Scorsese Presents: The Saints”) through his murderous work in Aleppo, and the crisis of conscience that finally hits him as he sees the cruel and repressive regime he works for at its most desperate.

“The Smuggler” is Marwan, a refugee-camp savvy African — played by the terrific French actor Omar Sy of “The Intouchables” and “The Book of Clarence” — who cynically makes his money buying disposable inflatable boats, disposable outboards and not-enough-life-jackets in Turkey to smuggle refugees to Greece.

“The Poet” (Ziad Bakri of “Screwdriver”) just wants to get his Syrian family of five out of Turkey and into Europe on Marwan’s boat.

And “The Captain” (Constantine Markoulakis of “The Telemachy”) commands a Hellenic Coast Guard vessel, a man haunted by the harrowing rescues he must carry out daily and visions of the bodies of those he doesn’t.

Andersen, a Tampa native who made his mark producing Tom Cruise spectacles (“American Made”), Mel Gibson B-movies (“Panama”) and the occasional “Everest” blockbuster, expands his short film “Refugee” to feature length for “I Was a Stranger.” He doesn’t so much alter the formula or reinvent this genre of film as find points of view that we seldom see that force us to reconsider what we believe through their eyes.

Sy’s Smuggler has a sickly little boy that he longs to take to Chicago. He runs his ill-gotten-gains operation, profiting off human misery, to realize that dream. We see glimpses of what might be compassion, but also bullying “customers” and his new North African assistant (Ayman Samman). Keeping up the hard front he shows one and all, we see him callously buy life jackets in the bazaar — never enough for every customer to have one in any given voyage.

The Captain sits for dinner with family and friends and has to listen to Greek prejudices and complaints about this human life and human rights crisis, which is how the worlds sees Greece reacting to this “invasion.” But as he and his first mate recount lives saved and the horrors of lives lost, that quibbling is silenced.

Here and there we see and hear (in Arabic and Greek with subtitles, and English) little moments of “rising above” human pettiness and cruelty and the simple blessings of kindness.

“I Was a Stranger” was finished in 2024 and arrives in cinemas at one of the bleakest moments in recent history. Cruelty is running amok, unchecked and unpunished. Countries are being destabilized, with the fans of alleged “strong man” rule cheering it on.

Andersen carefully avoids politics — Middle Eastern, Israeli, European and American — save for the opening scene’s zoom in on that Chicago hospital, passing a gaudily named “Trump” hotel in the process, and a general condemnation of Syria’s Assad mob family regime.

But Andersen’s bold movie, with its message so against the grain of current events, compromised media coverage and the mostly conservative audience that has become this film distributor’s base, plays like a wet slap back to reality.

And as any revival preacher will tell you, putting a positive message out there in front of millions is the only way to convert hundreds among the millions who have lost their way.

Rating: PG-13, violence, smoking, racial slurs

Cast: Yasmine Al Massri, Yahya Mahayni, Ziad Bakri, Omar Sy, Ayman Samman, Massa Daoud, Jason Beghe and Constantine Markoulakis

Credits: Scripted and directed by Brandt Andersen. An Angel Studios release.

Running time: 1:43

Related

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoHamas builds new terror regime in Gaza, recruiting teens amid problematic election

-

Business1 week ago

Business1 week agoGoogle is at last letting users swap out embarrassing Gmail addresses without losing their data

-

Indianapolis, IN1 week ago

Indianapolis, IN1 week agoIndianapolis Colts playoffs: Updated elimination scenario, AFC standings, playoff picture for Week 17

-

Southeast1 week ago

Southeast1 week agoTwo attorneys vanish during Florida fishing trip as ‘heartbroken’ wife pleads for help finding them

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoRoads could remain slick, icy Saturday morning in Philadelphia area, tracking another storm on the way

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoMost shocking examples of Chinese espionage uncovered by the US this year: ‘Just the tip of the iceberg’

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoMarijuana rescheduling would bring some immediate changes, but others will take time

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoPodcast: The 2025 EU-US relationship explained simply