Movie Reviews

‘Pinocchio’ Review: Guillermo del Toro’s Best Movie in a Decade Is a Stop-Motion Triumph

A decades-long ardour challenge leads to a traditional story given new life with beautiful craftsmanship and a poignant story of riot.

“Guillermo del Toro’s Pinocchio” reimagines the traditional fantasy story by way of probably the most beautifully-made stop-motion animation in years, a strong and life-affirming father-and-son story about acceptance and love within the face of ache, distress, and fascism, and the filmmaker’s love of monsters in what is definitely his finest movie in a decade.

The movie is ready in Nineteen Thirties Italy, as fascism is sweeping the nation. We see how harmful ideologies unfold rapidly and quietly at first, and what begins with simply the city’s blacksmith being a bit too obsessive about uniformity and order provides solution to hordes of fanatics screaming for Il Duce, children being despatched in addition camps, and everybody who’s totally different being excluded – or worse.

In the course of all this, we meet Geppetto, a humble woodcarver as soon as beloved by all and with a contented outlook on life. Issues change when he loses his son throughout a mindless air raid in town towards the tip of The Nice Battle, turning Geppetto right into a grief-stricken drunk who in the future curses god and the pure legal guidelines, and decides to convey his son again to life by carving a child-size puppet. David Bradley provides a implausible efficiency as Geppetto, however it’s the animation crew at ShadowMachine that pushes the boundaries of stop-motion animation to convey among the finest puppet performances in a movie.

When Geppetto breaks down and cries by his son’s grave, you not solely really feel the ache within the vocal efficiency, however you see the puppet’s issue respiratory, the trembling of his legs, the shaking of his fingers; even the garments transfer and stream naturally with the puppet’s physique, one thing we hardly ever see in stop-motion. Simply as Pinocchio’s picket physique is dropped at life by magic within the movie, so does del Toro, who directed alongside Mark Gustafson, and their military of over 40 animators breathe life into picket (nicely, technically plastic and silicone) puppets to create among the most beautiful performances in a movie this yr — animated or in any other case.

Each character strikes and behaves like a totally totally different particular person, with the performances being animated in 2s (which means animated half the frames {that a} common movie would) with a view to convey their imperfect actions to life. They’ve quirks and itches, they make errors, and so they shift weight when sitting down. In the meantime, cinematographer Frank Passingham brings live-action lighting and blocking strategies to the movie, making it seem like it was shot with pure mild and utilizing unfavorable area the best way Hayao Miyazaki does.

In his grief, Geppetto makes a picket boy. Like Victor Frankenstein, he tempers with powers he ought to depart alone, and his creation is unnatural, so this model of Pinocchio has extra in frequent with Frankenstein’s cobbled-together look than the uniform, cute look from the Disney model. Certainly, Geppetto’s work is left unfinished in terms of life, and he’s sort of ugly, and strikes extra like a J-horror monster.

In a number of methods, “Pinocchio” is a big center finger to the Disneyfication of each the unique Carlo Collodi story, and of fairy tales usually. Although this can be a film the entire household can see and get one thing out of, it by no means tones down the story for teenagers, nor does it discuss all the way down to them. The bones of the unique story stay, like Pinocchio’s time within the circus, the teachings he learns about being good, and the mess with the horrible dogfish (performed right here in a implausible Ray Harryhausen homage), however right here the story is reimagined as one in all riot towards expectations. The escape to the circus isn’t initially a sinful alternative of laziness, however a determined plea for acceptance and a rejection of the conformity and complacency of the fascist city’s college.

In case you anticipated the entire “set throughout Mussolini’s Italy” factor to be pure window dressing, assume once more, as a result of the specter of fascism informs each facet of the movie — all the way down to Pinocchio’s circus acts finally turning into propaganda exhibits supporting the military. The script, which del Toro has spent a decade making an attempt to get made, initially with Matthew Robbins, now with “Over the Backyard Wall” creator Patrick McHale, is all about disobedience, as soon as once more making what would in any other case be thought of a villainous monster into the story’s hero, the one one who sees the error in folks’s methods and rejects them.

Likewise, the movie doesn’t give Pinocchio the objective of being an actual boy, and it doesn’t shrink back from the horrors of actual life. The creature that provides Pinocchio life isn’t a conventional fairy, however a daunting and hauntingly lovely being that appears like a biblically correct angel, with wings stuffed with eyes — extra just like the Angel of Dying from “Hellboy II.” When Pinocchio first wakes up, he’s a little bit of a nightmare, an overtly curious little one thrown right into a world he doesn’t know, a child who smashes, breaks, and talks again with disrespect. His world isn’t one in all simple ethical classes and rewards, however a world stuffed with cruelty, loss of life, and violence. Like “Pan’s Labyrinth” and “The Satan’s Spine,” this can be a film set throughout a very merciless interval, centered on how kids coped and suffered. There may be some relatively ugly imagery, and it isn’t solely the villains who die horrible deaths.

And but, “Pinocchio” is way from a bitter or bleak movie. It’s about the great thing about life being fleeting, a film not a couple of monster who needs to be an actual boy, however a couple of monster that wishes his creator to like him the best way he’s, and to be accepted for who he’s. It is a film about imperfect fathers and imperfect sons, about not assembly expectations, and studying to reside with them, about accepting that life ends, that family members will depart us, and about embracing the time we had collectively. There’s horror, certain, but additionally heat, laughs, and loads of songs. Patrick McHale, who gave us the hit music of 2014 “Potatoes and Molasses” co-writes a number of songs with Roeban Katz and del Toro which can be as cheerful and catchy as they’re melancholic and profound. In the meantime, Alexandre Desplat’s rating is actually a non secular continuation of his “The Form of Water” rating, and it really works splendidly for the romantic tone of the movie.

There’s loads of comedy right here too, significantly due to Ewan McGregor’s sarcastic, would-be thinker Sebastian J. Cricket. The movie will get plenty of mileage out of visible gags involving his tiny stature and penchant for being smashed, and it really works each time. The place many star-studded animated motion pictures really feel like they lack precise performances, the solid right here disappears into their stop-motion characters to the purpose the place it isn’t all the time apparent who’s enjoying who.

Guillermo del Toro has spent over a decade making an attempt to get his dream stop-motion movie made, and in that point he’s advanced as a filmmaker. But “Pinocchio” looks like the most effective mixture of traditional del Toro and new del Toro, with the knowledge and melancholy that comes with age and expertise, but his bright-eyed love of fairy tales from his Spanish-language movies. Maybe extra spectacular is how “Pinocchio” pushes the oldest type of animation to new locations, and just like the puppet himself, breathes life into inanimate objects.

Grade: A

Netflix will launch “Pinocchio” in theaters this November earlier than a streaming premiere on December 9.

Signal Up: Keep on high of the newest breaking movie and TV information! Join our E-mail Newsletters right here.

Movie Reviews

Union movie review & film summary (2024) | Roger Ebert

When Amazon workers on Staten Island successfully voted to unionize in the spring of 2022, becoming the corporate retailer’s first American workplace to do so, it was hailed as one of the most important labor victories in the United States in nearly 100 years.

For the Amazon Labor Union (ALU) to organize employees at the JFK8 warehouse to vote in favor of union representation was a David versus Goliath story for the age of globalization — and a rousing reminder that collective grassroots efforts can still succeed despite massive employer concentration, management intimidation, and other hindrances to building worker power. And that an independent, worker-led coalition led the drive at this 8,000-plus-employee facility, rather than an established union, made its victory all the more impressive, even as the vote to unionize brought organizers into uncharted territory and set up a protracted legal battle with Amazon, which has since refused to recognize the ALU or negotiate a contract.

Telling the story of how the ALU reached this historic moment, “Union,” a new documentary co-directed by Brett Story (“The Hottest August”) and Stephen Maing (“Crime + Punishment”), takes a detail-driven, ground-level approach, following current and former Amazon employees in Staten Island as they mount a grassroots worker-to-worker campaign, standing their ground against one of the world’s powerful corporations all the while.

No talking-head documentary but a keenly observational chronicle of the unionization push and its aftermath, “Union” often plays like a thriller by virtue of its sharp, smart editing rhythms. Early on, Story and Maing juxtapose Jeff Bezos blasting off into space on a rocket made by his Blue Origin company and Amazon workers trudging wearily into work; it captures the unimaginable scale of the company’s operations while foregrounding the human scale often concealed by breathless (yet inevitably compromised) reporting of Amazon’s designs on empire.

Made over the course of three years, Story and Maing’s film explores the human cost of the convenience economy and illuminates oppressive working conditions in Amazon’s factories. From constant surveillance to high injury rates and a lack of breaks, the pressures of working in Amazon warehouses compound to create punishing environments for workers, ones Amazon has steadfastly refused to address or even accurately report. And the threat of retaliation against workers who organize is ever-present; in addition to pouring hundreds of millions of dollars into union-busting campaigns that include mandatory “captive audience” meetings (which have since been banned in the state of New York), Amazon issues warnings of possible termination to workers involved with the unionization drive.

Bookended by footage of vast cargo ships transporting goods, a reminder of the slow, perpetual motion with which the gears of modern capitalism grind on, Story and Maing’s film is smart in how systematically its narrative lays out obstacles to the union’s success. It also insightfully depicts ground-level dialogue between workers as a powerful tool with which to overcome them. Some of the most remarkable footage, inside Amazon headquarters, covertly films one of those captive audience meetings; here, the company’s anti-union propaganda (One reads: “We’re asking you to do three simple things: get the facts, ask questions and vote no to the union”) is disrupted by ALU organizers, who successfully push back on Amazon managers just long enough to make their case to workers.

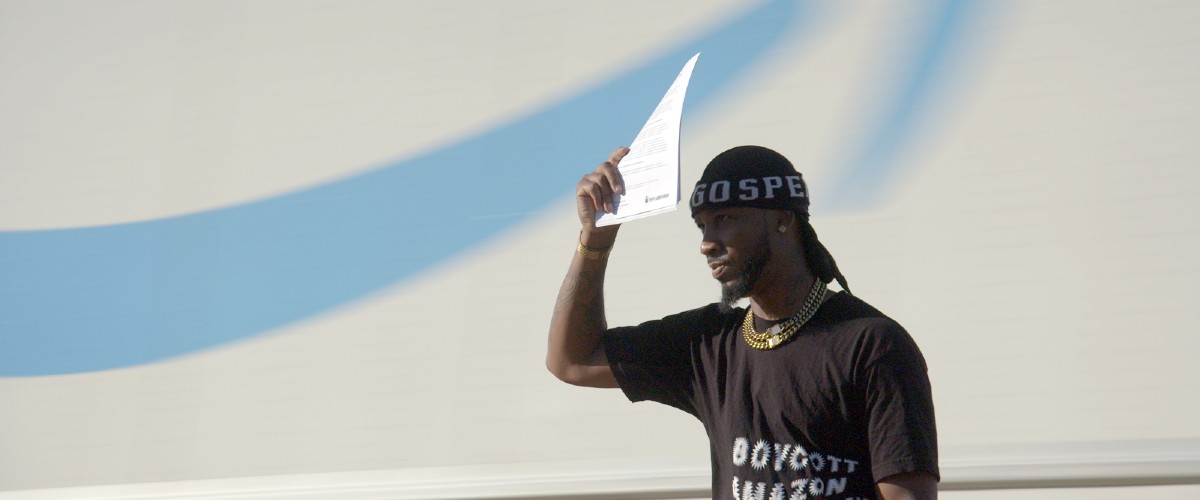

One of the ALU organizers, Chris Smalls, takes center stage in “Union,” though the documentary largely sidesteps the temptation to cast him as a conquering hero. (That’d be an easy trap, given that he became the organization’s public face across the period “Union” depicts.) Smalls, fired from Amazon after protesting inadequate PPE provision during the pandemic (and besmirched by the company’s general counsel as “not smart or articulate” in an internal meeting of executive leaders), is a father of three who was moved to activism by the flagrant injustice of the company’s abusive labor practices. As a leader, he’s at once charismatic and hard-charging, dedicated to his fellow “comrades” but ever driven to push forward even in the face of inter-union dissent.

One of the film’s great strengths is its ability to surface the multiplicity of tensions between organizers working toward a shared cause. Take the world of difference separating the experiences of two subjects: Maddie, a white college graduate using her campus activism experience to help the cause, and Natalie, an older Latina woman living out of her car for years. In one charged exchange, Natalie pushes back on the suggestion, made by white male organizers, that Chris intentionally gets himself arrested by New York police officers to draw attention to the unionization drive. Ultimately, Natalie’s dissatisfaction with the ALU—due to her disagreements with leadership as much as her desire to wait for larger union support—leads her to leave the organization. It’s a testament to the complexity of individual motivations and the absence of easy triumph in this type of effort.

“Union” documents the internal debates and disagreements over governance, organizing, and leadership strategies that divided the ALU before its successful unionization vote and were compounded by its subsequent failed attempt to unionize a second warehouse. Though Smalls’ force of personality, passion, and determination fueled the fight to unionize JFK8, the film carefully depicts this as a collective victory. It rarely gives in to the temptation to single out Smalls for praise at the expense of others, and making it clear that his leadership style also contributed to internal rifts in the ALU that at various points may have weakened its ability to further the union’s mission.

This becomes particularly important in the film’s latter half, after the unionization vote, at which point the sobering realities of the long work ahead come more fully into view. The heroism of the ALU organizers will never be in question. But with only one battle won in the war for workers’ rights, and Amazon continuing to contest or undercut its results by every means available, “Union” concludes on a note of weary fortitude rather than declarative victory. The film captures both the pain and the power of people at the base of a global infrastructure. By not departing from the frontlines of the fight against Amazon’s labor exploitation, Story and Maing bring the true face of their struggle into focus.

“Union” will be self-distributed theatrically, starting on Oct. 18. This review was filed from the film’s New York premiere at the New York Film Festival.

Movie Reviews

CTRL movie audience review: Ananya Panday’s Netflix thriller is ‘terrific’; OTT film gets thumbs-up from viewers | Today News

CTRL movie audience review: CTRL started streaming on Netflix on October 4. The thriller, directed by ace Bollywood director Vikramaditya Motwane, stars Ananya Panday and Vihaan Samat.

The story is about Nella and Joe, who seem like the ideal influencer couple. However, when Joe cheats on Nella, she uses an AI app to erase him from her life — only for it to gain control over her.

The Netflix movie has received some highly-positive reviews from viewers, who posted their comments on social media. Let’s take a look at some of those.

CTRL public reviews

“CTRL is… terrific, absorbing and made with a lot of finesse… Do watch if you have time.”

“Found Vikramaditya Motwane’s new Netflix film #CTRL utterly fascinating. So much to admire. An ambitious, timely, deeply uncomfortable screenlife thriller that’ll make you want to change your passwords, cover your webcam and move to the hills.”

“This is quite good. Only 1 hour 40 minutes, and not gonna lie, I had underestimated Motwane a bit with this movie. Ananya did well because she nailed this genre. It starts off slow, happy, and lighthearted, but the tension builds as the story progresses. Give it a watch, it’s nice.”

“vikramdityamotwane Gives a nuanced and gripping narrative and @ananyapandayy has finally come into her own, and does a fine job.”

“As a big fan of Motwane’s films, I’ve always seen him set new standards in mainstream cinema. From Udaan to AK vs AK he has always proved his merit. However, #CTRL feels like just an okay film, despite good casting with Ananya Panday. It lacks a strong impact and becomes somewhat preachy about our relationship with technology, leaving you with little to think about afterward.”

“The movie is abt how social media, AI and corporates are controlling us and not vice versa. Ananya Panday is good. Vihaan Samat is brilliant. The movie cudve been much better. Esp the climax.Theres no closure!”

Movie Reviews

Joker 2 Is So Bad It’s Almost Laughable

In 2019, a year now separated from us by enough catastrophic global events to feel like a remote archaeological era, the movie Joker, like it or not (I certainly didn’t), was a big deal. It won the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival and later garnered a leading 11 Oscar nominations, including Best Picture, with star Joaquin Phoenix eventually winning Best Actor for his performance as a mentally ill would-be stand-up comic turned murderous clown. The movie also became the subject of heated discussion and not a little hand-wringing. Would its portrait of the comic-book villain as the lonely, misunderstood victim of mistreatment by a vaguely defined “society” inspire copycat acts of mayhem? Joker may have teetered uneasily in the balance between critiquing incel violence and being a commercial for it, but thankfully its many admirers kept their enthusiasm contained to the box office, where the film raked in over a billion dollars worldwide, shattering the all-time record for an R-rated movie.

Five years later, Joker’s director and co-writer Todd Phillips has returned with a sequel that swerves in an unseen—and on paper, intriguing—new direction: Our miserable antihero has become, of all things, the singing, dancing protagonist in his own private musical. A lot of things could be said about Phillips’ execution of that idea, most of them deservedly negative. By any reasonable measure this is a terrible movie, too long and too self-serious and way too dramatically inert, a regrettable waste of its lead actors’ boundless commitment to even their most thinly written roles. But no one could accuse Joker: Folie à Deux of being a mere cash grab, lazily recycling its predecessor’s mood, themes, or plot structure.

There’s an admirable boldness to Phillips’ decision to cast a pop supernova like Lady Gaga opposite the darkly charismatic Phoenix, then ask them both to sing, live-to-film, a jukebox-musical soundtrack of more than a dozen well-known songs that range from 1940s Broadway standards (“Bewitched, Bothered and Bewildered,” from Pal Joey) to 1970s easy-listening pop (the Carpenters’ “Close to You”). Granted, the director fails to clear the bar he sets for himself—fails hard enough, at times, to scrape the skin off his legs from knee to ankle—but it’s fair to say that this movie’s problems have little if anything to do with the attempted magic trick of its premise. It’s mainly the weirdness of that trick, and the stars’ doomed dedication to pulling it off, that renders Joker: Folie à Deux even minimally watchable.

Joker ended with Phoenix’s Arthur Fleck locked up in a mental institution but seemingly on the verge of escaping to start his career as Batman’s archnemesis. Instead, Folie à Deux finds Arthur still locked up in Gotham City’s inhumane Arkham State Hospital. Having been judged competent in a sanity hearing, Arthur is about to go on trial for the murders of five people, one of them on live television. (As he confesses to more people than he probably should, the number is really six if you include his mother.) Outside the institution’s grimy walls, he has become a folk hero to a certain set of clown-mask-sporting nihilists and a tabloid bogeyman to the public at large. But inside the hospital, Arthur remains a pitiable loser, mocked by his fellow inmates and singled out for alternately friendly and cruel treatment by an Irish prison guard (Brendan Gleeson).

Phillips’ desire to mess with the audience’s genre expectations is evident from the jump. The first thing the audience sees, after a vintage WB logo, is a cartoon short entitled “Me and My Shadow,” animated by the Triplets of Belleville filmmaker Sylvain Chomet in a style reminiscent of classic Looney Tunes. In it, Arthur’s shadow self emerges from his body to commit crimes that the real man is then blamed for. The plot of the cartoon is a literalization of the defense that his sympathetic lawyer (Catherine Keener) will later use in court: Arthur, she believes, is the victim of dissociative identity disorder, a former abused child who’s made up the Joker character as a way to vent his otherwise inaccessible rage. It’s not clear whether the movie wants us to agree with her assessment or with that of Gotham assistant district attorney Harvey Dent (Industry’s Harry Lawtey), who thinks Arthur is merely a sociopath faking mental illness in order to escape the consequences he deserves.

Meanwhile, Lee Quinzel (Gaga), an arsonist serving time in Arkham’s minimum-security wing, has a very different vision of the Joker: She’s a groupie, having followed his crime spree in the news and obsessively rewatched a TV biopic about him. (Even fans who haven’t consumed the aggressive marketing won’t take long to recognize her as the future Harley Quinn.) When they’re put in the same music-therapy group—a place where cheery sing-alongs are touted as a wholesome counterpoint to the grimness of asylum life—Lee and Arthur bond instantly and soon develop their own more twisted motives for bursting into song. When they’re together, or apart and thinking of each other, their internal monologues bubble to the surface as ready-made classics of the American songbook. This despite the fact that Lee, for her part, seems not to be a big fan of the musical genre. When the asylum shows the MGM classic The Band Wagon on movie night, Lee gets so bored she sets fire to the rec-room piano. Not liking The Band Wagon should surely serve as a red flag for any prospective suitor, but Lee redeems her taste later on, when the by-then-besotted couple belts out a cover of that musical’s most enduring number, “That’s Entertainment.”

Joker: Folie à Deux is hardly the first musical to posit the idea of its song-and-dance sequences as the emanations of a delusional mind, but it must be among the ones that hammer hardest on that conceit. In scene after scene, often with hardly a break for dialogue in between, either Lee, Arthur, or both in unison will channel the intensity of an emotional moment by delivering a breathy version of some beloved pop hit or other. Invisible string orchestras may swoop in to accompany these flights of fancy, just as they would in a Hollywood musical, but the secondary characters never join in and seldom seem to notice that a serenade is taking place. With rare exceptions (like the rock-’em-sock-’em Gaga cover of “That’s Life” that plays under the closing credits), most of the vocal performances in Folie à Deux are purposely underwhelming in terms of virtuosity: They’re husky, scratchy, and in Phoenix’s case often half-spoken, suited more for a tipsy karaoke night than for the Broadway stage.

Gaga has pointed out in interviews that neither her nor Phoenix’s character is a professional entertainer, so why should they sing like one? It’s a reasonable point, as is a less polite one she doesn’t make: that if she sang full-out instead of curbing her usual vocal splendor, the contrast would place Phoenix’s adequate but limited baritone in unflattering relief. But what makes the songs, irresistible toe-tappers all, start to blur into a drab wall of sound has less to do with the performance quality than with the nonstop onslaught of musical numbers and the sluggishness of the story in between. Other than the building of internal emotion to the point that it must express itself in song—over and over and over—precious little happens in Folie à Deux. Arthur is declared fit to stand trial, goes to court, and is marched back by the cruel guards each night to the bleakness of his cell. A few familiar characters from the first Joker, including Zazie Beetz as Arthur’s former neighbor, show up to take the stand, and at one point a horrific act of violence interrupts the proceedings. But the forward motion of the story is so minimal, and so broken up by long stretches of musical stasis, that the result barely feels like a movie. It’s more like a work of Joker fanfic, created not just by the credited screenwriters (Phillips and Scott Silver, who also co-wrote the 2019 film) but by Phoenix and Gaga themselves in what was apparently a collaborative project to revise the script in real time during the shoot.

The fact that Folie à Deux has the self-referential quality of fanfic does not necessarily mean it will go down well with actual Joker fans, who seem likely to come out scratching their heads over a sequel about a comic-book supervillain that contains virtually no fight scenes, a single car chase that ends roughly a minute after it begins, and scarcely a moment that could be classified as suspenseful. The main question to be answered by the viewer is not “What will happen next?” but “Is all this taking place in the real world, or just inside their heads?”—an epistemological puzzle that is not enough in itself to sustain our energy for nearly two hours and 20 minutes. Even more confoundingly, all this time spent locked in the psyches of two deeply disturbed characters gives us little insight into their motivations. The pathetic Arthur Fleck remains, as I called him in my review of the 2019 movie, a “poor little clownsie-wownsie,” while Gaga’s Lee is so underwritten we remain unsure to the end whether she is a vulnerable fangirl or a heartless femme fatale. If he is, as the lyric from “That’s Entertainment” goes, “the clown with his pants falling down,” does that make her simply “the skirt who is doing him dirt”? To make Gaga’s character little more than a mirror that reflects the Joker back to himself (in alternately flattering and unflattering ways) is a real squandering of this powerhouse performer, whose life experience as a stadium-filling superstar has given her no shortage of insight into the psychology of fame monsters.

Without spoiling the ending, it’s safe to say that with it, Phillips seems to foreclose the likelihood that anyone will be begging for more. That’s probably a blessing for both the filmmaker and us, since this somber, muddled, maudlin film seems to have been made by someone who holds his characters and his audience in contempt.

-

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25439572/VRG_TEC_Textless.jpg)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25439572/VRG_TEC_Textless.jpg) Technology3 days ago

Technology3 days agoCharter will offer Peacock for free with some cable subscriptions next year

-

World2 days ago

World2 days agoUkrainian stronghold Vuhledar falls to Russian offensive after two years of bombardment

-

World3 days ago

World3 days agoWikiLeaks’ Julian Assange says he pleaded ‘guilty to journalism’ in order to be freed

-

Technology2 days ago

Technology2 days agoBeware of fraudsters posing as government officials trying to steal your cash

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoSecret Service agent accused of sexually assaulting Harris campaign staffer: report

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoPutin outlines new rules for Russian use of vast nuclear arsenal

-

Sports24 hours ago

Sports24 hours agoFreddie Freeman says his ankle sprain is worst injury he's ever tried to play through

-

Virginia4 days ago

Virginia4 days agoStatus for Daniels and Green still uncertain for this week against Virginia Tech; Reuben done for season