Entertainment

Hollywood has finally paid attention to Deaf culture. Three new novels go even deeper

On the Shelf

New novels in regards to the Deaf world

True Biz

By Sara Novic

Random Home: 400 pages, $28

The Dolphin Home

By Audrey Schulman

Europa: 320 pages, $27

The Signal for Residence

By Blair Fell

Atria: 416 pages, $27

In case you purchase books linked on our website, The Occasions might earn a fee from Bookshop.org, whose charges assist impartial bookstores.

Illustration issues. For many years, it’s been a constant chorus throughout my interviews with everybody from ladies environmentalists to Black sports activities executives to Native American administrators. Nevertheless it’s solely within the aftermath of latest controversies (#OscarSoWhite) and horrors (the homicide of George Floyd and hate crimes towards Asians) that the world appeared to begin listening.

Illustration is at the very least tilting in the appropriate route, with extra Latinos starring in bilingual TV reveals, extra Black playwrights on Broadway, extra life like homosexual characters and extra ladies administrators.

A casting director lately identified, nonetheless, that one group remains to be often left behind: folks with disabilities. That’s beginning to shift too, at the very least for the Deaf and onerous of listening to. After industrial successes like “Creed” and “A Quiet Place” that featured deaf characters in secondary roles, Hollywood has thrown its weight behind films through which deafness is central, with final yr’s Oscar nomination for “Sound of Steel” adopted by Sunday’s greatest image trophy for “CODA.”

The tales of deaf persons are lastly being informed in novels too. Historically, there have been few distinguished deaf novelists, particularly amongst those that had been born with out listening to. (Donald Harington wrote greater than a dozen novels after shedding nearly all his listening to resulting from meningitis at age 12; romance novelist Connie Briscoe totally misplaced her listening to at age 30.) There have additionally been few deaf characters in novels by listening to authors, with Carson McCullers’ “The Coronary heart Is a Lonely Hunter” being a notable exception.

However April brings three new novels that revolve round deaf or hard-of- listening to protagonists as they try to seek out their manner within the listening to world. Even higher, the books all do greater than merely create empathy for characters with disabilities; regardless of their flaws, all are thought-provoking and entertaining, with vividly drawn and complicated folks.

Essentially the most notable is “True Biz,” the second novel from Sara Novic, as a result of she is the lone deaf creator among the many trio. (The phrase refers back to the ASL signal that interprets as “actual speak.”) The ebook’s focus is Charlie, a teenage lady with minimal listening to whose mother and father opted for cochlear implants as an alternative of educating her signal language. After years of struggling in isolation at public colleges, she lastly will get to study ASL and attend an area college for the Deaf and finds a brand new world opening up for her, even because it challenges her in new methods. (The ebook has already been optioned for a TV collection to star Millicent Simmonds of “The Quiet Place.”)

Blair Fell, who makes his debut in “The Signal for Residence,” has been an ASL interpreter since 1993. “The Signal” follows each Arlo, a younger deafblind man dealing with previous traumas whereas searching for independence, in addition to his new middle-aged interpreter, Cyril, who can be grappling with inside ache. Arlo has been minimize off from a lot of the world by his overbearing non secular household, but he thrives each time given a possibility to attach. A poignant scene through which he’s studying and writing about Walt Whitman permits us to see the multitudes he accommodates.

Audrey Schulman’s sixth ebook, “The Dolphin Home,” stands exterior of Deaf tradition … however that too makes a degree. The novel, set totally on the island of St. Thomas in 1965, focuses on Cora, a younger girl who is nearly fully deaf. With out her glasses, which function a listening to support, she reads lips and muddles by way of life with out signal language.

Cora’s deafness has made her a eager observer of physique language, nonetheless; this pays off in quite a few methods when she stumbles right into a job working with dolphins for a staff of scientists. The dolphins train her about their fears and needs even earlier than she teaches them language. The lads usually do the identical with their our bodies and actions, versus their phrases.

In the end, Schulman is extra within the dynamics between people and animals and between Cora and the older males. But the isolation Cora feels exterior of any Deaf group is in its personal manner a take a look at Deaf tradition, as a result of it’s usually a truth of life for folks with out listening to.

As a listening to particular person, I’m in no place to dissect how properly these authors seize the nuances of the deaf expertise. However it will presumably be true of the vast majority of readers. I might additionally presume that each one three authors, listening to or not, need their books judged on the deserves. All three really feel too lengthy, however solely Schulman’s really drags, repeating materials and typically even phrases. It’s also, regardless of its sharply noticed characters (together with the dolphins), considerably humorless.

The opposite two have that first-novel drawback through which the creator overpacks the work with all of the drama they’ll cram in and the factors they wish to make. (Novic is on her second ebook, however her acclaimed first effort, “Woman at Warfare,” was by no means about deafness.)

Fell briefly digresses from the story to ship Cyril to a convention the place he learns about new approaches to signing, Haptics and Protactile signing, that present extra info (such because the speaker’s physique language and tone). Although the part is basically didactic, the idea — and due to this fact the scene — is riveting and related to the story.

Novic inserts frequent classes, ostensibly ready by a trainer on the college, and dives into minor characters to no considerable level. These breaks disrupt narrative momentum, though some are fascinating, just like the “Deaf President Now” pupil revolt towards the board at Gallaudet College.

She’s at her greatest when she weaves concepts in organically: a confrontation between Charlie’s roommate, Kayla, who’s Black, and Charlie’s romantic curiosity Austin, who’s white (and privileged and oblivious), easily integrates the historical past of Black American Signal Language.

And Charlie’s coming-of-age story — her rage at her mom’s push for extra surgical procedure and implants over ASL, her growing relationships in school — is a shifting and compelling argument about being Deaf as an id, not a incapacity, and a strong exploration of the worry of extinction as science improves listening to expertise.

“9 out of ten deaf youngsters had listening to mother and father, and people mother and father held Deaf destiny of their palms — the destiny of their very own kids, in fact, and the way forward for the Deaf group at massive,” she writes. “Drawback being, most mother and father understood deafness solely as defined to them by medical professionals: as a treachery of their genes, one thing to be drilled out.”

There may be nonetheless a way of the creator attempting to teach right here, nevertheless it comes throughout the context of character and narrative. And at this level, the listening to actually do have lots to find out about Deaf tradition and methods to create a extra simply society. So even when Novic and Fell tilt towards didacticism, it’s for good purpose. Perhaps sometime somebody can write the Nice American Novel a few deaf character with out having to make the ebook all about their deafness. However at this stage in our social evolution it appears unfair to ask that of most any novel. So long as we now have a rustic the place nominating a Black girl for the Supreme Court docket results in one facet trotting out racial canine whistles, we’re in for fairly a wait.

Within the meantime, spend a number of hours with Cora, Arlo, Charlie and at the same time as you see how difficult life is for them in a listening to society, you’ll begin to perceive the depth of their want to be understood on their very own phrases, in their very own language.

Movie Reviews

Catherine Breillat Is Back, Baby

The transgressive French filmmaker is in fine, fucked-up form with Last Summer, about a middle-age lawyer who starts sleeping with her stepson.

Photo: Janus Films

When Anne (Léa Drucker) has sex with her 17-year-old stepson, she closes and sometimes covers her eyes. It’s a pose that brings to mind what people say about the tradition of draping a napkin over your head before eating ortolan, that the idea is to prevent God from witnessing what you’re about to do. Théo (Samuel Kircher) is as fine-boned as any songbird — “You’re so slim!” Anne gasps in what sounds almost like pain during one of their encounters, as she runs her hands up his rangy torso — and just as forbidden. And despite the fact that what she’s doing could blow up her life, she can’t stay away. It wouldn’t be fair to say that desire is a form of madness in Last Summer, a family drama as masterfully propulsive as a horror movie. Anne remains upsettingly clear-eyed about what’s happening, as though to suggest otherwise would be a cop-out. But desire is powerful, enough to compel this bourgeois middle-age professional into betraying everything she stands for in a few breathtaking turns.

Last Summer is the first film in a decade from director Catherine Breillat, the taboo-loving legend behind the likes of Fat Girl and Romance. Last Summer, which Breillat and co-writer Pascal Bonitzer adapted from the 2019 Danish film Queen of Hearts, could be described as tame only in comparison to Rocco Siffredi drinking a teacup full of tampon water in Anatomy of Hell, but there is a lulling sleekness to the way it lays out its setting that turns out to be deceptive. Anne and her husband Pierre (Olivier Rabourdin) live with their two adopted daughters in a handsome house surrounded by sun-dappled countryside, a lifestyle sustained by the business dealings that frequently require Pierre to travel. Anne’s sister and closest friend Mina (Clotilde Courau) works as a manicurist in town, and conversations between the two make it clear that they didn’t grow up in the kind of ease Anne currently enjoys. It’s a luxury that allows her to pursue a career that seems more driven by idealism than by financial concerns. Anne is a lawyer who represents survivors of sexual assault, a detail that isn’t ironic, exactly, so much as it represents just how much individual actions can be divorced from broader beliefs.

In the opening scene, Anne dispassionately questions an underage client about her sexual history. She informs the girl that she should expect the defense to paint her as promiscuous before reassuring her that judges are accustomed to this tactic. The sequence outlines how familiar Anne is with the narratives used to discredit accusers, but also highlights a certain flintiness to her character. Drucker’s performance is impressively hard-edged even before Anne ends up in bed with her stepson. There’s a restlessness to the character behind the sleek blonde hair and businesswoman shifts, a desire to think of herself as unlike other women and as more interesting than the buttoned-up normies her husband brings by for dinner. Anne enjoys her well-coiffed life, but she also feels impatient with it, and when Théo gets dropped into her lap after being expelled from school in Geneva for punching his teacher, he triggers something in her that’s not just about lust. Théo is still very much a kid, something Breillat emphasizes by showcasing the messes he leaves around the house as much as on his sulky, half-formed beauty. But that rebelliousness speaks to Anne, who finds something invigorating in aligning herself with callow passion and impulsiveness instead of stultifying adulthood — however temporarily.

This being a Breillat film, the sex is Last Summer’s proving ground, the place where all those tensions about gender and class and age meet up with the inexorability of the flesh. The first time Anne sleeps with Théo, it’s shot from below, as though the camera’s lying in bed beside the woman as she looks up at the boy on top of her. It’s a point of view that makes the audience complicit in the scene, but that also dares you not to find its spectacle hot. Breillat is an avid button-pusher responsible for some of the more disturbing depictions of sexuality to have ever been committed to screen, but Last Summer refuses to defang its main character by portraying her simply as a predatory molester. Instead, she’s something more complicated — a woman trying to have things both ways, to dabble in the transgressive without risking her advantageous perch in the mainstream, and to wield the weapons of the victim-blaming society she otherwise battles when they are to her advantage. It’s not the sex that harms Théo; it’s the mindfuck of what he’s subjected to. After dreamily playing tourist in Théo’s youthful existence, Anne drags him into the brutal realities of the grown-up world. The results are unflinching and breathtakingly ugly. You couldn’t be blamed for wanting to look away.

See All

Entertainment

Review: In the underpowered 'Daddio,' the proverbial cab ride from hell could use more hell

The art of conversation has been a casualty in these deeply divided days of ours, and the poor state of talk in the movies — so often expositional, glib or posturing — is an unfortunate reflection of that. The new film “Daddio” is an attempt to put verbal discourse front and center, confining to a yellow taxi a pair with different life paths, as you would expect when your leads are Sean Penn and Dakota Johnson. (Guess which one is the cabbie.)

Johnson’s coolly elegant, nameless traveler, a computer programmer returning to New York’s JFK airport from a trip visiting a big sister in Oklahoma, may be getting a flat rate for her journey, but the meter’s always running on the mouth of Penn’s gleefully crusty and opinionated driver, Clark. He’s a twice-married man prone to streetwise philosophizing about the state of the world and, over the course of the ride, the unsettled romances of his attractive fare. And as she drops clues about her life — sometimes unwittingly, then a little more freely — she gives back with some probing responses of her own, trying to pry him open.

Writer-director Christy Hall, who originally conceived the scenario as a stage play, lets the chatter roll — there’s a significant stretch in which the cab isn’t even moving. And when silence sets in, there’s still an exchange to tend to, as Johnson occasionally, with apprehension, responds to a lover’s insistent sexting. This third figure (unseen, save one predictable picture sent to her phone) becomes another source of conjectural bravado for Clark, a self-proclaimed expert in male-female relations, who makes eye contact through the rearview mirror.

Sean Penn in the movie “Daddio.”

(Sony Pictures Classics)

Watching the unremarkable “Daddio,” you’ll never worry that anything untoward or combustible will happen between the chauvinist driver with a heart of gold and the smart if vulnerable young female passenger who “can handle herself,” as Clark frequently observes. That lack of tension is the problem. The movie is less about a nuanced conversation between strangers than a writer’s careful construction, designed to bridge a cultural impasse between the sexes. Hall is so eager to stage a big moment that upends expectations and triggers wet-eyed epiphanies — He’s a compassionate blowhard! She can laugh at his crassness! — that we’re never allowed to feel the molecules shift from moment to moment in a way that isn’t unforced. Life may be the subject, but life is what’s missing.

It doesn’t help that in directing her first feature, Hall has given herself one of the hardest jobs, getting the most out of only two ingredients and one container. It’s probably why Jim Jarmusch went the variety route with five different tales for his memorable 1991 taxi suite “Night on Earth.” That film conveyed a palpable sense of time and space.

“Daddio,” on the other hand, is nowhere near as assured visually or in its pacing. Hall has an experienced cinematographer in Phedon Papamichael (“Nebraska,” “Ford v Ferrari”) but chooses an unfortunate studio gloss that suggests utter control, rather than a what-might-happen vibe. Not that there’s anything wrong with a movie so clearly made on a set. But Johnson’s well-rehearsed poise and Penn’s coasting boldness make them seem like the stars of a commercial for a scent called Common Ground rather than flesh-and-blood people. At times, they hardly seem to be sharing the same car interior, leaving “Daddio” feeling like a safe space, when what it needs is danger.

‘Daddio’

Rating: R, for language throughout, sexual material and brief graphic nudity

Running time: 1 hour, 41 minutes

Playing: In limited release Friday, June 28

Movie Reviews

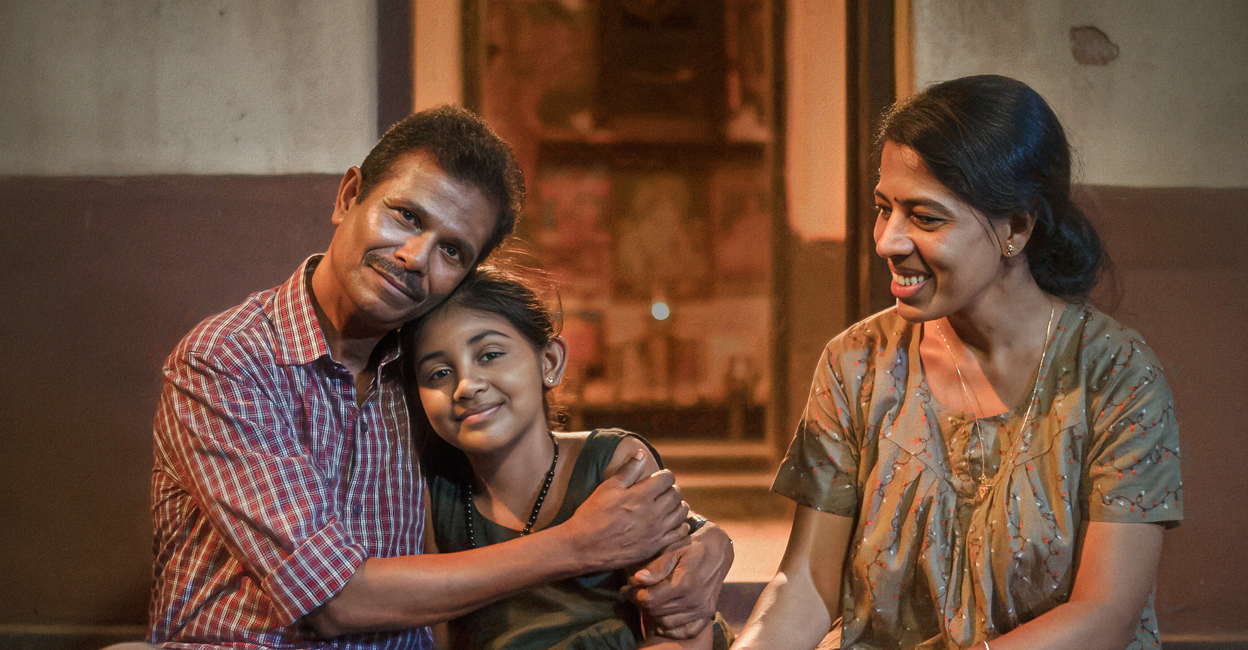

‘Kunddala Puranam’ Review | A simplistic tale featuring an in-form Indrans, Remya Suresh

‘Kunddala Puranam’, starring Indrans and Remya Suresh in the lead, is the kind of movie you might want to watch for its focus on village folk and their everyday lives, offering a break from the bustling city. However, its far too simplistic approach may not work for all, especially at a time when filmmakers are trying to break new ground with experimental storytelling, unique styles, and mixing genres.

‘Kunddala Puranam’, directed by Santhosh Puthukkunnu, is set in Kasaragod, where a family opens up their private well to their neighbors. The well is an often-used trope in Malayalam cinema, with women characters gathering around it for water and some gossip. Venu (Indrans) and Thankamani (Remya Suresh) have a school-going daughter who yearns to wear gold earrings but can’t because of an ear infection. When her condition improves, Venu, who works as a security guard at a local bar, decides to purchase a pair for her. The gold earrings soon become the source of both happiness and unhappiness for the family.

The Kasaragod dialect, explored in films since the latter half of the last decade, has a certain charm, but what is particularly interesting is how Indrans effortlessly mouths his dialogues in the dialect. He is a masterclass in emotional acting and nails his role as a resolute father in this film. Remya Suresh, who played a prominent role in last year’s acclaimed movie ‘1001 Nunakal’, performs exceptionally well in this movie. Unni Raja, best known for ‘Thinkalazhcha Nishchayam’, also plays an interesting character. However, it is the child actor Sivaani Shibin who manages to capture the audience’s hearts with her playful innocence, a quality sadly missing in characters written for children in recent years.

Though the writers have tried their hand at humor in the movie, most of the dialogues fall flat, except for some scenes involving a drunkard and the other villagers. The story, though interesting, is stretched too long for comfort. Sound designer and musician Blesson Thomas manages to capture the mood of the story well through his music.

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoRead the Ruling by the Virginia Court of Appeals

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoTracking a Single Day at the National Domestic Violence Hotline

-

Fitness1 week ago

Fitness1 week agoWhat's the Least Amount of Exercise I Can Get Away With?

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoSupreme Court upholds law barring domestic abusers from owning guns in major Second Amendment ruling | CNN Politics

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoTrump classified docs judge to weigh alleged 'unlawful' appointment of Special Counsel Jack Smith

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoSupreme Court upholds federal gun ban for those under domestic violence restraining orders

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoNewsom seeks to restrict students' cellphone use in schools: 'Harming the mental health of our youth'

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoTrump VP hopeful proves he can tap into billionaire GOP donors