Education

How Trump’s crackdown on Harvard and other universities is affecting the world

Universities are an easy target for right-wing populists. Polls show that a lot of Americans consider them too liberal, too expensive and too elitist, and not entirely without reason. But the fight between the Trump administration and Harvard is something more: It has become a test for the president’s ability to impose his political agenda on all 2,600 universities in the United States. Students, professors and scientists are all feeling the pressure, and that could undermine the dominant position that American science has enjoyed for decades.

What does that mean for the world?

European countries are wooing U.S.-based scientists, offering them “scientific refuge” or, as one French minister put it, “a light in the darkness.” Canada has attracted several prominent American academics, including three tenured Yale professors who study authoritarianism and fascism. The Australian Strategic Institute described this moment as “a once-in-a-century brain gain opportunity.”

In the mid-20th century, America was seen by many as a benign power, committed to scientific freedom and democracy. It attracted the best brains fleeing fascism and authoritarianism in Europe.

Today, the biggest beneficiary could be China and Chinese universities, which have been trying to recruit world-class scientific talent for years. Now Mr. Trump is doing their work for them. One indication of the success of China’s campaign to attract the best and brightest is Africa, the world’s youngest continent. Africans are learning Mandarin in growing numbers. Nearly twice as many study in China as in America.

Could America gamble away its scientific supremacy in the service of ideology? It has happened before. Under the Nazis, Germany lost its scientific edge to America in the space of a few years. As a German, my brain may wander too readily to the lessons of the 1930s, but in this case the analogy feels instructive. Several of my colleagues covering the fallout from the crackdown on international students and researchers pointed to Hitler’s silencing of scientists and intellectuals.

No one region can currently replicate the magic sauce of resources, freedom, a culture of risk-taking and welcoming immigrants that made America the engine of scientific innovation. But if it tumbles as a scientific superpower, and potential breakthroughs are disrupted, it would be a setback for the whole world. I spoke to my colleagues who are reporting on this, and here’s what I found out.

Higher education

There’s going to be fallout. We’ve talked to researchers at Harvard whose funding was cut, including those working on tuberculosis, and another who engineers fake organs that are useful in the study of human illnesses. There have been all sorts of different projects disrupted that could have led to some major breakthrough. When research is interrupted, there is no way of knowing if it would have led to a breakthrough that the world will now have to do without. But the impact might actually be more heavily felt on small regional public universities that had already lost some of their public funding and were relying heavily on international students to pay the bills. So if the United States is continually viewed as an unwelcome place for international students there will be ripple effects throughout the system.

Politics

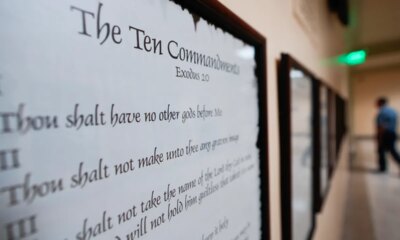

It’s smart to think about this in terms of political calculus instead of ultimate goals. It matters little to the Trump administration if it’s dragged into court over and over again, or even how many of those lawsuits it wins. They view Harvard as an avatar for all universities that have become incubators of liberalism and are hostile to conservatives. And what better university in the world to send a message that, in their view, slows down the march of liberalism in universities. That would be a major victory for this administration. If Trump officials have any measure of success, it will be whether they can create a roadmap for imposing their political agenda on the other 2,000-plus colleges in the United States.

Global economics

Even before Trump, American researchers were saying we have a problem with the supply of domestic science, math and engineering talent. And that’s something that takes a generation to fix. It’s not something that’s done overnight. Some, we’ve already seen, are looking to do research elsewhere because, one, their funding has been cut, and, two, they’re very worried about academic freedom. Can they study what they want? We haven’t seen people ask these questions since the McCarthy era, the anti-liberal ideological war of the 1950s. Take climate change: there’s basically a repudiation by conservatives in power of what most of the scientific community considers established trends and facts based on evidence. It’s very difficult for foreign countries to compete financially, but what I have noticed in all of their pitches courting American scientists — whether it’s in Australia or Europe or Latin America — is that they’re offering them freedom of inquiry and respect of facts.

Canada

We have seen a movement of American academic and scientific talent to Canada. And that reinforces the clear success of Canadian institutions before this all happened. I spoke to Timothy Snyder, a prominent American academic who recently moved to Toronto. He told me that this is a huge opportunity for Toronto. He said the city could become what London, Paris and New York were in different periods when the great and the good moved there to think about democracy and talk about the future. Canada, and especially the University of Toronto, he believes, have a special role to play in fostering an ideological counterpull to Trump’s America in this moment of great turmoil. It’s not so much that people are setting up an American resistance in Canada, but rather that the city is part of a global intellectual resistance to Trump.

India

I don’t sense a big change in the mood in India yet. The United States still holds a lot of soft power and remains very attractive to Indians. In fact, many Indians are seeing something that is pretty familiar to them. They’re saying, “Welcome to the world as we have experienced it for the past few years.” The government under Narendra Modi has definitely cracked down on free speech. It has tried to quash dissenting voices, and it has also leaned on academics and has tried to squeeze certain research institutions that it considers too liberal. And there has been a demonization of the Muslim minority, which make up about 15 percent of the population. There are a lot of similarities to Trump’s America. Everyone in the world is just trying to understand what Trump’s actions mean for their own countries. So India’s experience can be instructive in making sense of this moment.

China

China really wants to become a center for international education, because it sees that as a key ingredient for building its reputation as a global superpower. American universities have long been a source of American soft power. China wants Chinese universities to be a source of Chinese soft power. And now Trump is doing their work for them. You can see that in China’s rhetoric and messaging. It’s trying to portray itself as open and international, everything that the Trump administration is turning away from.

In reality, China isn’t a model of openness. There are a lot of restrictions on and suspicions toward foreigners in general, and that includes foreign students. But against the backdrop of what Trump is doing, China’s message may seem more convincing. Will it work? So far China has had the most luck with Chinese-born scientists who have studied and worked in America. They already had been riding out a wave of anti-Asian racism in the United States, as well as accusations of being spies. But now, if they also don’t have the resources to do their work because Trump has cut research funding, there is no reason for them to stay. Meanwhile, China has been pouring huge amounts of money into research and development. And so they are well positioned to take advantage of this brain drain.

Africa

Young Africans have this sense that the world is changing, that there’s a shift underway. And instead of going to the West, instead of lining up outside the American embassy and facing visa rejections, many are heading to new educational hubs — and especially to China. China enters the conversation because it provides the kind of opportunities young students are looking for. Many are attracted by the scholarships, by the easier access to visas, the affordable tuition and the comparatively cheap cost of living, which is prohibitive for so many people. And this shift is happening even as China trains thousands of African officials annually in fields such as science, technology and military strategy.

It’s not that young Africans wouldn’t choose Harvard if they were offered a chance. It’s all about opportunity for them. And where there is opportunity, soft power follows. America used to have that. Students were going there not just because they wanted a world-class education, but because they saw America as a symbol of modernity, democracy and progress – values they hoped to bring back home. Today, that image has been eroded, and China stands to gain the most from it.

Europe

One university, Aix Marseille University, in southern France, immediately offered 15 positions to American researchers in reaction to the Trump administration’s policies. It began as a symbolic gesture. The university president said, “We’re offering a light in darkness.” What that one university is doing for individual American researchers is amazing. But it’s just a small drop in the bucket. There is an international system generating leaps and bounds in science, the motor and the anchor of which has been the United States. And if you get rid of the motor and you get rid of the anchor, it’s pretty hard to rebuild those things on the fly.

For example, NASA and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration have these databases that they have maintained and that scientists around the world use. Some of the people I spoke to in Europe said, ‘Look, if we’re only going to spend 100 million euros, it would be much smarter to secure these databases.’ It’s not just that the United States has been a center in terms of people coming together and pushing science forward; it’s also been the data library for scientists everywhere. Think of all the health data that USAID has been financing around the world. It’s gone. Universities and researchers say that what’s at stake are not just individual jobs, but the greater research ecosystem.

Science

A lot of scientists said to me that they’re seeing the possibility of America tumbling from this position of scientific supremacy as Germany did under Hitler. What happened to Germany in the 1930s was not something anybody saw coming. All of a sudden, in a historical blink of an eye, the whole picture changed.The United States took over as the scientific superpower, using a lot of German scientists and a lot of German concepts and ideas. The question today is: is that happening again? And if so, who will take the lead? Could it be Europe? Could it be China? It’s hard to imagine somebody graduating with a physics degree from the University of Utah and then moving right to Beijing and continuing as before, raising kids in the suburbs, right? But one thing to keep in mind is that the smartest people in the world are also the least limited in their mobility. Scientists are wanted everywhere. They’re the ones who will fly free. Where they’ll land I’m not sure, but you just cannot keep them if they don’t want to be there. They’re too smart and too mobile.

Education

After F.B.I. Raid, Los Angeles School Board Discusses Superintendent

Board members are having an emergency meeting a day after agents raided the home and office of Alberto Carvalho, the Los Angeles Unified School District superintendent. The F.B.I. also searched the Florida home of a consultant with ties to the schools chief.

Education

How A.I.-Generated Videos Are Distorting Your Child’s YouTube Feed

Experts caution that low-quality, A.I.-generated videos on YouTube geared toward children often feature conflicting information, lack plot structure and can be cognitively overwhelming — all of which could affect young children’s development.

Education

Video: Blizzard Slams Northeast with Heavy Snow, Disrupting Travel

new video loaded: Blizzard Slams Northeast with Heavy Snow, Disrupting Travel

transcript

transcript

Blizzard Slams Northeast with Heavy Snow, Disrupting Travel

Several cities across the Northeast received at least two feet of snow, bringing many places to a standstill.

-

“I hope our students enjoy their snow day today and stay warm and safe throughout, but I do have some tough news to share. School will be in-person tomorrow. You can still pelt me with snowballs when you see me.” “It’s probably about the worst I’ve seen. I mean, I was here with the last big storm. I think that was where in 2016 or something. But it wasn’t as bad as this. And the problem is, when the plows come past, they just throw up all the snow. And there’s going to be a big bank here later. So I’m digging it out now to get rid of some of this.” “I do ski patrol on the Lower East Side. I like to check the parks, and sometimes I find people fall in the snow and they can’t get up, like a elderly gentleman went out in his pajamas to get a quart of milk. So, things like that.” “And if you can cook at home, please do so instead of ordering food to be delivered given the conditions. Make an enormous pot of soup and bring some to your neighbors upstairs.”

By Meg Felling

February 23, 2026

-

World1 day ago

World1 day agoExclusive: DeepSeek withholds latest AI model from US chipmakers including Nvidia, sources say

-

Massachusetts2 days ago

Massachusetts2 days agoMother and daughter injured in Taunton house explosion

-

Montana1 week ago

Montana1 week ago2026 MHSA Montana Wrestling State Championship Brackets And Results – FloWrestling

-

Oklahoma1 week ago

Oklahoma1 week agoWildfires rage in Oklahoma as thousands urged to evacuate a small city

-

Louisiana4 days ago

Louisiana4 days agoWildfire near Gum Swamp Road in Livingston Parish now under control; more than 200 acres burned

-

Technology6 days ago

Technology6 days agoYouTube TV billing scam emails are hitting inboxes

-

Denver, CO2 days ago

Denver, CO2 days ago10 acres charred, 5 injured in Thornton grass fire, evacuation orders lifted

-

Technology6 days ago

Technology6 days agoStellantis is in a crisis of its own making