Education

As New York Students Shed Masks, Elation Mixes With Trepidation

SANDS POINT, N.Y. — Simply earlier than courses started on Wednesday morning, Jordan Goldberg, a fifth grader at Guggenheim Elementary Faculty on Lengthy Island, strode by way of the doorways and stopped brief.

“This doesn’t really feel regular!” he mentioned, clutching his naked, unmasked chin.

For the primary time since colleges reopened throughout the pandemic, Jordan and lots of different public faculty college students throughout the state entered homerooms, gymnasiums and sophistication with out masks. Citing low virus caseloads and a want to return to a way of normalcy, Gov. Kathy Hochul lifted the state’s faculty masks mandate beginning Wednesday, leaving masks coverage to native officers.

However with low vaccination charges amongst minors and the specter of the coronavirus nonetheless current, if lessened, what as soon as had been anticipated as a milestone second was as an alternative met with a blended response.

From college students to academics to folks, the frenzy of fresh-faced jubilation on Wednesday was tempered by issues: On one aspect was a perception that the order was lengthy overdue; on the opposite was a concern that the choice was dangerously untimely.

“It seems like Covid is form of over, despite the fact that it isn’t,” mentioned Jordan, 11, after first interval started and the preliminary rush of masklessness wore off. “It seems like everybody simply form of gave up on it.”

With the statewide mandate lifted, native officers are actually left to determine masks coverage of their colleges. In Nassau County, the Port Washington Union Free Faculty District, which incorporates Guggenheim, leapt on the earliest likelihood to shed masks. However New York Metropolis’s a million public faculty college students must wait till no less than Monday, when Mayor Eric Adams has mentioned he expects to raise the masks requirement.

As faces within the schoolyard at Guggenheim started to look as they did within the Earlier than Occasions of the 2019 faculty 12 months, the brand new protocols had been met with feelings that ranged from elation to trepidation.

“I feel it feels nice!” mentioned Mario Alfonso-Paz, 9, his masks in his pocket and dimples seen as he beamed between posters of Dr. Seuss characters in a Guggenheim hallway. “It’s prefer it’s lastly over!”

However his mom, Silvia Alfonso, who placed on a masks to enter the college foyer, didn’t share her son’s pleasure.

Ms. Alfonso mentioned she had hypertension and her husband had kind 1 diabetes, preconditions that made them weak to severe problems from the coronavirus. She fears her unmasked son may carry the virus residence.

All through the pandemic, she mentioned, they’ve informed their kids that “they need to put them on — for us.” She is permitting her son to go maskless however mentioned: “I feel it nonetheless wasn’t a good suggestion, as a result of individuals are being contaminated.”

At Guggenheim, plenty of academics, a few of whom are older and extra weak to extreme sickness from Covid, had expressed deep nervousness about eradicating masks, mentioned the principal, Kimberly Licato. Within the days main as much as the rule change, she had the college steerage counselor meet with some workers in addition to college students to assist them deal with fears.

Michael Hynes, the Port Washington colleges superintendent, additionally despatched a video message to the college group forbidding bullying of those that continued to put on a masks. At Guggenheim some academics mentioned that they had taught modules on tolerance to organize the scholars.

With a teal N95 masks strapped tightly over her nostril and mouth, Virginia McMahon, 59, a substitute trainer, lead a category of first graders — most of whom had been unmasked — within the Pledge of Allegiance on Wednesday morning. Her masks would keep put, she mentioned.

“Despite the fact that I’m triple vaxxed now, I simply don’t wish to take any possibilities,” Ms. McMahon mentioned. “I feel it’s prudent, for me.”

As of final week, the Facilities for Illness Management and Prevention recommends faculty masking in communities experiencing excessive ranges of the virus.

Statewide, about 40 p.c of youngsters age 5 to 11 and simply over three-quarters of youngsters 12 to 17 years outdated have obtained one vaccine dose, in accordance with knowledge collected by the New York State Division of Well being, although vaccination charges differ starkly by area and even amongst ethnic teams.

And kids 4 and below — who’re nonetheless ineligible for vaccines — have been overrepresented amongst kids in coronavirus hospitalizations in New York, in accordance with a research carried out in early January by the Well being Division.

The constellation of things has lead some well being specialists to name the choice harmful. Dr. Uché Blackstock, a physician whose apply focuses on well being fairness, mentioned that pupil vaccination charges — particularly in New York Metropolis, the place they differ broadly —- are the explanation her kids, metropolis public faculty college students, would stay masked. “Eradicating masks insurance policies in these colleges is harmful,” she wrote on Twitter.

Others, like Dr. Lucy McBride, an internist based mostly in Washington, D.C., consider its time has come: She is a part of a gaggle of well being care professionals who’ve pushed to finish masking in colleges for the reason that Omicron wave started in January.

“Masks had been at all times meant to be a short lived intervention,” Dr. McBride mentioned. “We’re having a tough time letting go of an intervention and a mandate that was maybe applicable at one other time however doesn’t match the present second.”

The top of obligatory faculty masking has not ended the talk; the governor has left open the chance that obligatory masking will resume if virus instances return up.

In December, a gaggle of 14 mother and father, most from Lengthy Island, efficiently sued the state over the college masking coverage, saying the imposition of the mandate is past the scope of the state’s energy. The case, which targets the mechanism that permits such guidelines to be made, just isn’t affected by the rescinded mandate. It’s making its method by way of the New York State Courtroom of Appeals.

“It was by no means about masks,” mentioned Chad LaVeglia, a lawyer for individuals who are suing. “It was merely about giving mother and father the selection to make choices for his or her children.”

In Shannon Grennan’s kindergarten class, some kids’s mother and father had despatched her notes asking for her assist in protecting their baby masked; others had left it as much as the youngsters to determine.

A few of her 5- and 6-year-old college students had flung off their masks with a thrill on the faculty’s double doorways, however a couple of kids who sat coloring at their desks had been nonetheless masked. At one level, when Ms. Grennan taught a lesson on the climate, asking kids what they might placed on to remain heat outdoors, a hand went up: “A face masks!”

As college students navigated their modified actuality on Wednesday, the masks divide typically was current inside a single household. Harris Baltch mentioned that one in every of his kids plans to put on a masks in class; the opposite is not going to.

“That is undoubtedly in some ways a welcome change, however we’ll see the way it goes,” Mr. Baltch, 39, mentioned, including that he would have most popular ready longer. “Hopefully they don’t begin getting sick yet again.”

Close by, Laura McEnaney rejoiced as she kissed her 11-year-old twins goodbye for the day and reminded them to maintain their maskless chins up and look straight forward. Each boys are particular wants, mentioned Ms. McEnaney, who has spoken out at college board conferences towards masks. She has felt that face coverings had been detrimental to their capacity to speak and skim feelings.

“I don’t suppose they need to have ever been masked — ever,” Ms. McEnaney mentioned. “This could have been finished a very long time in the past, and I feel the children have suffered.”

Annie Correal contributed reporting.

Education

Video: Police Use Pepper Spray on Protesters on G.W.U.’s Campus

new video loaded: Police Use Pepper Spray on Protesters on G.W.U.’s Campus

transcript

transcript

Police Use Pepper Spray on Protesters on G.W.U.’s Campus

Police officers arrested 33 pro-Palestinian protesters and cleared a tent encampment on the campus of George Washingon University.

-

“The Metropolitan Police Department. If you are currently on George Washington University property, you are in violation of D.C. Code 22-3302, unlawful entry on property.” “Back up, dude, back up. You’re going to get locked up tonight — back up.” “Free, free Palestine.” “What the [expletive] are you doing?” [expletives] “I can’t stop — [expletives].”

Recent episodes in Israel-Hamas War

Education

How Counterprotesters at U.C.L.A. Provoked Violence, Unchecked for Hours

A satellite image of the UCLA campus.

On Tuesday night, violence erupted at an encampment that pro-Palestinian protesters had set up on April 25.

The image is annotated to show the extent of the pro-Palestinian encampment, which takes up the width of the plaza between Powell Library and Royce Hall.

The clashes began after counterprotesters tried to dismantle the encampment’s barricade. Pro-Palestinian protesters rushed to rebuild it, and violence ensued.

Arrows denote pro-Israeli counterprotesters moving towards the barricade at the edge of the encampment. Arrows show pro-Palestinian counterprotesters moving up against the same barricade.

Police arrived hours later, but they did not intervene immediately.

An arrow denotes police arriving from the same direction as the counterprotesters and moving towards the barricade.

A New York Times examination of more than 100 videos from clashes at the University of California, Los Angeles, found that violence ebbed and flowed for nearly five hours, mostly with little or no police intervention. The violence had been instigated by dozens of people who are seen in videos counterprotesting the encampment.

The videos showed counterprotesters attacking students in the pro-Palestinian encampment for several hours, including beating them with sticks, using chemical sprays and launching fireworks as weapons. As of Friday, no arrests had been made in connection with the attack.

To build a timeline of the events that night, The Times analyzed two livestreams, along with social media videos captured by journalists and witnesses.

The melee began when a group of counterprotesters started tearing away metal barriers that had been in place to cordon off pro-Palestinian protesters. Hours earlier, U.C.L.A. officials had declared the encampment illegal.

Security personnel hired by the university are seen in yellow vests standing to the side throughout the incident. A university spokesperson declined to comment on the security staff’s response.

Mel Buer/The Real News Network

It is not clear how the counterprotest was organized or what allegiances people committing the violence had. The videos show many of the counterprotesters were wearing pro-Israel slogans on their clothing. Some counterprotesters blared music, including Israel’s national anthem, a Hebrew children’s song and “Harbu Darbu,” an Israeli song about the Israel Defense Forces’ campaign in Gaza.

As counterprotesters tossed away metal barricades, one of them was seen trying to strike a person near the encampment, and another threw a piece of wood into it — some of the first signs of violence.

Attacks on the encampment continued for nearly three hours before police arrived.

Counterprotesters shot fireworks toward the encampment at least six times, according to videos analyzed by The Times. One of them went off inside, causing protesters to scream. Another exploded at the edge of the encampment. One was thrown in the direction of a group of protesters who were carrying an injured person out of the encampment.

Mel Buer/The Real News Network

Some counterprotesters sprayed chemicals both into the encampment and directly at people’s faces.

Sean Beckner-Carmitchel via Reuters

At times, counterprotesters swarmed individuals — sometimes a group descended on a single person. They could be seen punching, kicking and attacking people with makeshift weapons, including sticks, traffic cones and wooden boards.

StringersHub via Associated Press, Sergio Olmos/Calmatters

In one video, protesters sheltering inside the encampment can be heard yelling, “Do not engage! Hold the line!”

In some instances, protesters in the encampment are seen fighting back, using chemical spray on counterprotesters trying to tear down barricades or swiping at them with sticks.

Except for a brief attempt to capture a loudspeaker used by counterprotesters, and water bottles being tossed out of the encampment, none of the videos analyzed by The Times show any clear instance of encampment protesters initiating confrontations with counterprotesters beyond defending the barricades.

Shortly before 1 a.m. — more than two hours after the violence erupted — a spokesperson with the mayor’s office posted a statement that said U.C.L.A officials had called the Los Angeles Police Department for help and they were responding “immediately.”

Officers from a separate law enforcement agency — the California Highway Patrol — began assembling nearby, at about 1:45 a.m. Riot police with the L.A.P.D. joined them a few minutes later. Counterprotesters applauded their arrival, chanting “U.S.A., U.S.A., U.S.A.!”

Just four minutes after the officers arrived, counterprotesters attacked a man standing dozens of feet from the officers.

Twenty minutes after police arrive, a video shows a counterprotester spraying a chemical toward the encampment during a scuffle over a metal barricade. Another counterprotester can be seen punching someone in the head near the encampment after swinging a plank at barricades.

Fifteen minutes later, while those in the encampment chanted “Free, free Palestine,” counterprotesters organized a rush toward the barricades. During the rush, a counterprotester pulls away a metal barricade from a woman, yelling “You stand no chance, old lady.”

Throughout the intermittent violence, officers were captured on video standing about 300 feet away from the area for roughly an hour, without stepping in.

It was not until 2:42 a.m. that officers began to move toward the encampment, after which counterprotesters dispersed and the night’s violence between the two camps mostly subsided.

The L.A.P.D. and the California Highway Patrol did not answer questions from The Times about their responses on Tuesday night, deferring to U.C.L.A.

While declining to answer specific questions, a university spokesperson provided a statement to The Times from Mary Osako, U.C.L.A.’s vice chancellor of strategic communications: “We are carefully examining our security processes from that night and are grateful to U.C. President Michael Drake for also calling for an investigation. We are grateful that the fire department and medical personnel were on the scene that night.”

L.A.P.D. officers were seen putting on protective gear and walking toward the barricade around 2:50 a.m. They stood in between the encampment and the counterprotest group, and the counterprotesters began dispersing.

While police continued to stand outside the encampment, a video filmed at 3:32 a.m. shows a man who was walking away from the scene being attacked by a counterprotester, then dragged and pummeled by others. An editor at the U.C.L.A. student newspaper, the Daily Bruin, told The Times the man was a journalist at the paper, and that they were walking with other student journalists who had been covering the violence. The editor said she had also been punched and sprayed in the eyes with a chemical.

On Wednesday, U.C.L.A.’s chancellor, Gene Block, issued a statement calling the actions by “instigators” who attacked the encampment unacceptable. A spokesperson for California Gov. Gavin Newsom criticized campus law enforcement’s delayed response and said it demands answers.

Los Angeles Jewish and Muslim organizations also condemned the attacks. Hussam Ayloush, the director of the Greater Los Angeles Area office of the Council on American-Islamic Relations, called on the California attorney general to investigate the lack of police response. The Jewish Federation Los Angeles blamed U.C.L.A. officials for creating an unsafe environment over months and said the officials had “been systemically slow to respond when law enforcement is desperately needed.”

Fifteen people were reportedly injured in the attack, according to a letter sent by the president of the University of California system to the board of regents.

The night after the attack began, law enforcement warned pro-Palestinian demonstrators to leave the encampment or be arrested. By early Thursday morning, police had dismantled the encampment and arrested more than 200 people from the encampment.

Education

Video: President Biden Addresses Campus Protests

new video loaded: President Biden Addresses Campus Protests

transcript

transcript

President Biden Addresses Campus Protests

President Biden defended the right of demonstrators to protest peacefully, but condemned the “chaos” that has prevailed at many colleges nationwide.

-

Violent protest is not protected. Peaceful protest is. It’s against the law when violence occurs. Destroying property is not a peaceful protest. It’s against the law. Vandalism, trespassing, breaking windows, shutting down campuses, forcing the cancellation of classes and graduations — none of this is a peaceful protest. Threatening people, intimidating people, instilling fear in people is not peaceful protest. It’s against the law. Dissent is essential to democracy, but dissent must never lead to disorder or to denying the rights of others, so students can finish the semester and their college education. There’s the right to protest, but not the right to cause chaos. People have the right to get an education, the right to get a degree, the right to walk across the campus safely without fear of being attacked. But let’s be clear about this as well. There should be no place on any campus — no place in America — for antisemitism or threats of violence against Jewish students. There is no place for hate speech or violence of any kind, whether it’s antisemitism, Islamophobia or discrimination against Arab Americans or Palestinian Americans. It’s simply wrong. There’s no place for racism in America.

Recent episodes in Politics

-

Education1 week ago

Education1 week agoVideo: President Biden Addresses Campus Protests

-

Movie Reviews1 week ago

Movie Reviews1 week agoSabari Movie Review: Varalaxmi Proves She Can Do Female Centric Roles

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoEuropean elections: What do voters want? What have candidates pledged?

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoWhistleblower Joshua Dean, who raised concerns about Boeing jets, dies at 45

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoAustralian lawmakers send letter urging Biden to drop case against Julian Assange on World Press Freedom Day

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoBrussels, my love? Champage cracked open to celebrate the Big Bang

-

News1 week ago

A group of Republicans has united to defend the legitimacy of US elections and those who run them

-

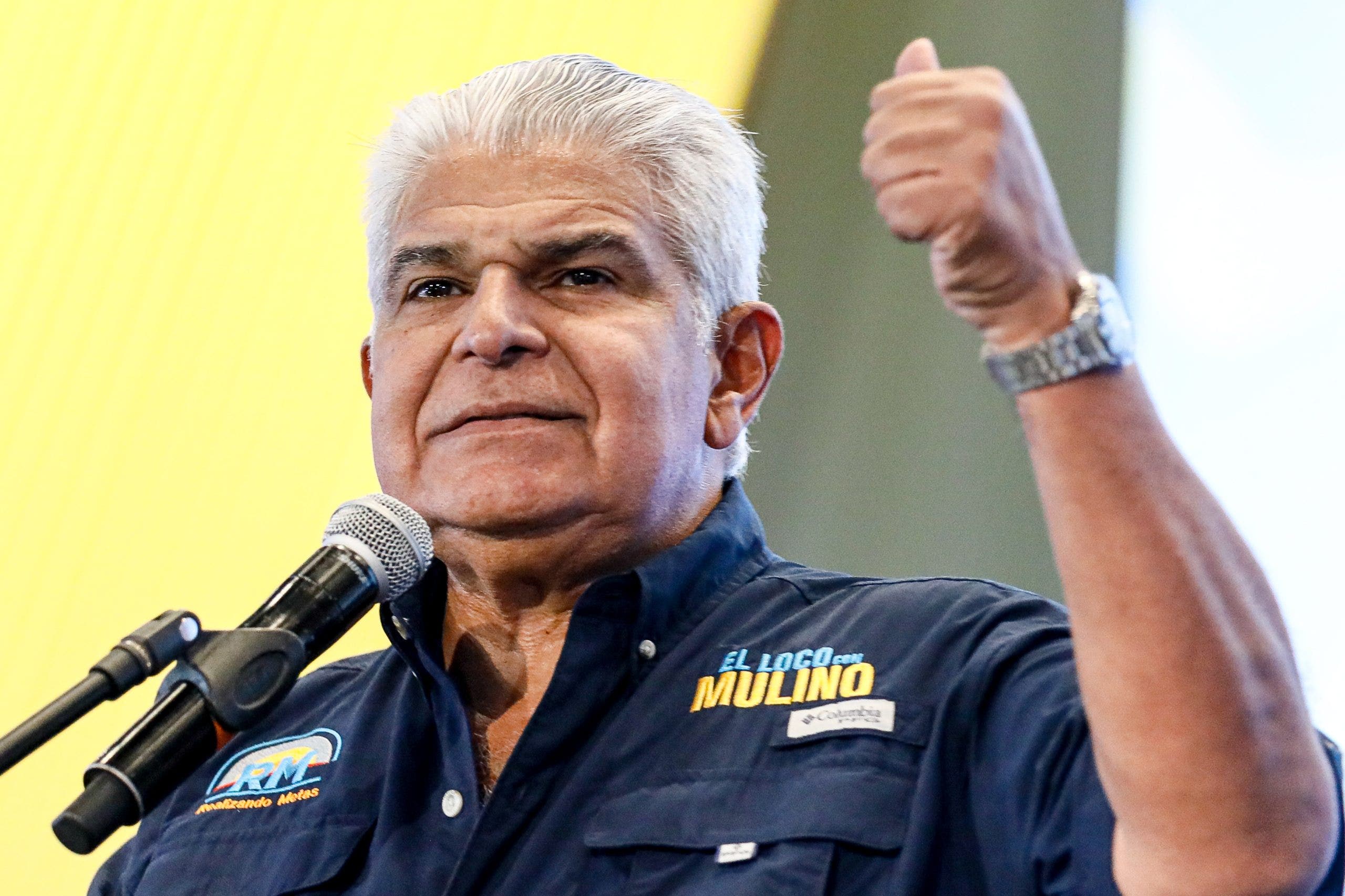

Politics7 days ago

Politics7 days agoHouse Dems seeking re-election seemingly reverse course, call on Biden to 'bring order to the southern border'

:quality(70)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/shawmedia/KVEEDIYM7ND7HMZQ6534A6DJCQ.png)