Culture

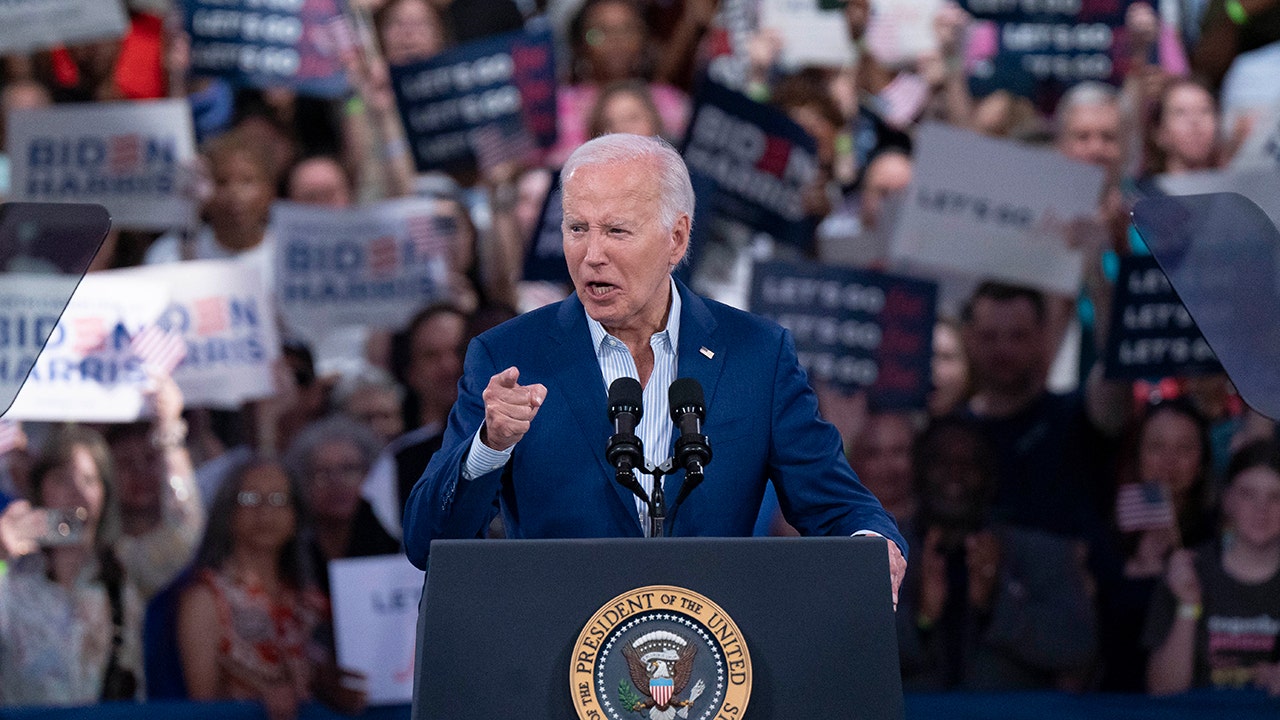

She Moved From the Chem Lab to the Kitchen, but Not by Choice

Welcome to Group Textual content, a month-to-month column for readers and guide golf equipment concerning the novels, memoirs and story collections that make you need to discuss, ask questions and dwell in one other world for a bit of bit longer.

________

Listed here are a couple of phrases I detest together with fiction written by girls: Sassy. Feisty. Madcap. These supposedly complimentary adjectives have a method of canceling out the very qualities they’re meant to explain: Opinionated. Humorous. Clever. This final one is to not be confused with its patronizing cousin, Intelligent. Don’t even get me began on Gutsy, Spunky and Frisky — the unlucky spawn of Relatable.

With that out of the best way, let’s discuss LESSONS IN CHEMISTRY, by Bonnie Garmus (Doubleday, 386 pp., $29), a debut novel a few scientist within the Nineteen Sixties who’s opinionated, humorous and clever, full cease. Sadly, Elizabeth Zott has been unceremoniously and brutally sidelined by male colleagues who make Don Draper appear to be a SNAG (Delicate New Age Man).

How, precisely, she was cheated out of a doctorate and misplaced the love of her life — Calvin Evans, a kindred scientist, knowledgeable rower and the daddy of her daughter, Madeline — are central parts within the story, however feminism is the catalyst that makes it fizz like hydrochloric acid on limestone.

Elizabeth Zott doesn’t have “moxie”; she has braveness. She not a “woman boss” or a “girl chemist”; she’s a groundbreaker and an knowledgeable in abiogenesis (“the speculation that life rose from simplistic, non-life kinds,” in case you didn’t know). Not lengthy after Zott converts her kitchen right into a lab geared up with beakers, pipettes and a centrifuge, she will get hoodwinked into internet hosting a staid tv cooking present referred to as “Supper at Six.” However she isn’t going to smile and browse the cue playing cards. Zott ad-libs her method into a task that fits her, treating the creation of a stew or a casserole as a grand experiment to be undertaken with utmost seriousness. Suppose molecular gastronomy in an period when canned soup reigned supreme. Baked into every episode is a wholesome serving of empowerment, with not one of the frill we now have come to affiliate with that time period.

Along with her severe take a look at the frustrations of a era of girls, Garmus provides loads of lighthearted enjoyable. There’s a thriller involving Calvin’s household and a take a look at the politics and dysfunction of the native tv station. There’s Zott’s love affair with rowing and her unconventional method to parenthood and her deep connection to her canine, Six-Thirty.

Nonetheless, past the entertaining subplots and witty dialogue is the onerous fact that, in 1961, a sensible, bold girl had restricted choices. We see how a scientist relegated to the kitchen discovered a solution to pursue a watered-down model of her personal dream. We see how two girls working in the identical lab had no selection however to activate one another. We meet Zott’s pal and neighbor, Harriet, who’s trapped in a depressing marriage to a person who complains that she smells.

“Classes in Chemistry” could also be described with one or all of my verboten phrases, and it’d find yourself shelved in that maddeningly named part “Ladies’s Fiction,” which must go the best way of the girdle. To file Elizabeth Zott among the many pink razors of the guide world is to overlook the sharpness of Garmus’s message. “Classes in Chemistry” will make you surprise about all of the real-life girls born forward of their time — girls who have been sidelined, ignored and worse as a result of they weren’t as resourceful, decided and fortunate as Elizabeth Zott. She’s a reminder of how far we’ve come, but in addition how far we nonetheless should go.

Dialogue Questions

-

What do science and rowing have in widespread? Why do you assume Garmus determined to dedicate so many pages to the game?

-

Apart from her presumption that her daughter is presented, how is Zott’s method to parenthood 50 years forward of its time?

Steered Studying

“The place’d You Go, Bernadette,” by Maria Semple. You’ll be able to’t get to know Elizabeth Zott with out waxing nostalgic about Bernadette Fox, the unique tortured, inscrutable, cynical but susceptible protagonist who couldn’t care much less what you assume. When you haven’t learn this guide by now, we undoubtedly aren’t associates. Sorry, the film doesn’t rely; equating the 2 is like forfeiting a visit to Italy since you’ve eaten a can of SpaghettiOs.

“Lab Woman,” by Hope Jahren. All in favour of studying a extra hopeful — and true — account of a lady in science? Begin with this memoir from a professor of geobiology who’s now on the College of Oslo. Our critic referred to as it “a gifted trainer’s street map to the key lives of vegetation — a guide that, at its finest, does for botany what Oliver Sacks’s essays did for neurology, what Stephen Jay Gould’s writings did for paleontology.” (Jahren additionally will get props for exhibiting “the usually absurd hoops that analysis scientists should leap by way of to acquire even minimal financing for his or her work.”)

Culture

Meet Tony Hawk's skateboarding protégé, an 11-year-old X Games medalist and Eminem fan

A relaxing afternoon for Reese Nelson can include perfecting a new version of a nose grab 720 in San Diego wearing her favorite Eminem shirt. Perhaps figuring out new ways to perform a kickflip nose slide to fakie. Maybe doing NBDs — “never been done” tricks — that can help her win X Games Ventura 2024 this weekend.

All with Tony Hawk watching in the background. Yes, that Tony Hawk. It’s the scenario when an 11-year-old skateboarding prodigy gets to train with the sport’s long-time GOAT.

Flip the script, and picture a stressful afternoon for Nelson. Playing dress-up with her cat, Bloody Mary, can be hectic, particularly when Mary isn’t as cooperative as Nelson’s other cat, Freddy Krueger. Then there are those occasions when Nelson and her younger sister quarrel while playing with their dolls. And let’s not forget when that game of Minecraft has a lousy ending.

Some might wonder why the aforementioned examples aren’t flipped. Playing with dolls and pets should be a joy. Doing insane tricks that require a skate lingo guide for non-fans on a vert ramp standing nearly 15 feet — tricks the world’s best skateboarders attempt (successfully and unsuccessfully) daily — should be the avoidable obstacles. For Nelson, the youngest-ever X Games medalist after last year’s effort in California, the harder the trick, the more determined she is to master it.

She knows her current lifestyle is challenging, but she puts on a protective helmet and pads every day to make personal battles with a vert ramp look like lightweight work. Her greatness is supported by a generational talent in Hawk, who has dominated the skateboarding scene since turning pro at 14 years old. It’s her tenacity, fearlessness and relentlessness that reminds him of a younger version of himself.

“She chooses the highest-level tricks to learn, and she follows through with them. At some point, she started making up some of her own,” Hawk said. “I’m talking about tricks that had never been considered in our realm, and she was doing them for the first time at the age of 10, 11.

“She is way ahead of anyone her age — or at any age, for the most part. It’s like she skipped all of the foundational steps in skateboarding to get to some of the most elite tricks.”

Add that incredible ability with tons of humility and a charming personality, and you get Nelson, a happy-go-lucky skateboarder who won over fans globally at X Games 2023, earning a silver medal in the Pacifico Women’s Skateboard Vert at 10 years and 8 months old. X Games 2024 runs Friday through Sunday in Ventura, Calif., and Sunday afternoon, Nelson once again will compete in the event and be tested on her execution of control, originality and overall use of the vert ramp.

Winning a gold medal Sunday would be an honor. Competing for the love of the sport, however, is what organically puts a smile on the face of the incoming seventh-grader who turns 12 in November. Some X Games competitors are viewing this weekend as win or bust. To Nelson, this is still just fun and games — and that’s OK.

Even if many skateboarding fans already consider her a wunderkind.

“Very quickly, I could tell that she had something extraordinary,” Hawk said.

Born in Calgary, Alberta, Nelson and her family moved to San Diego roughly three years ago as a result of her dad’s occupation. Nelson’s household isn’t full of skateboarders. Nobody encouraged her to attempt ramp tricks. But as a 4-year-old, she learned to snowboard during the Canadian winters, and when her family moved to California, she was introduced to skateboarding and skate parks at 8.

With practice, she learned to control a skateboard, then she tried maneuvering on a vert ramp. That turned into a hobby. Now, this hobby has developed into something that’s given Nelson a spotlight she never imagined.

“It sort of just happened,” Nelson said. “I was just skating for fun, and then I started competing. I don’t know, everything just really happened at once.”

“She’d already caught the skating bug in Canada but didn’t have a lot of facilities there that suited what she was interested in, which was more vertical, half-pipe skating,” Hawk added. “When they moved, they realized they were in the epicenter of vert skating.”

Nelson first would learn to perform tricks on small ramps. She then began working with one of Hawk’s friends, pro skater Lincoln Ueda, who also works with members of the Chinese national team. Hawk took a phone call from Ueda that concluded with an emphatic message.

“He said, ‘You’ve got to see this little girl,’” Hawk said.

After viewing some of Nelson’s performance videos, Hawk received contact information for Nelson’s mother, Lindsey Bedier, and sent her a direct message through social media. He invited the family to his warehouse, where Nelson showcased her skills in person.

“It was crazy. I said to my husband, ‘Tony Hawk just DMed me,’” Bedier said. “Everyone thinks we moved to California for skateboarding, but we’re just not that hardcore. It was so crazy when he DMed.”

Nelson put on a show during their first encounter, and Hawk ultimately extended Nelson membership to his Birdhouse Skateboards team. Since then, the two have become quite close. It’s a businesslike mentor-mentee relationship some days, two friends acting goofy on others.

There are also those days when Nelson forgets Tony Hawk is the Tony Hawk. He has a lengthy list of accomplishments, which includes being the first to successfully complete a recorded 900 (2 1/2 full revolutions) in 1999. Nelson’s initial thoughts of the skateboarding legend are slightly different from those older than her, expected considering she wasn’t born when Hawk, now 56, was the face of the sport in the 1990s and 2000s.

Nelson often is reminded of how famous her mentor is. Whether it’s a food run to P.F. Chang’s (chicken fried rice is her favorite) or an event at a skate park, if she is with Hawk, she sees how excited his fan base gets. It doesn’t mean she understands the hype. Blame timing, as Nelson was born in 2012.

“I always think it’s weird how people just come up and want pictures,” Nelson said of Hawk.

“When we first went (to the warehouse), she was just like, ‘Oh, cool … like, let’s skate,’” Bedier added, laughing. “She had no idea.”

Hawk has a funnier interpretation of their relationship. As arguably the most well-known skateboarding mentor, Hawk can only shake his head when Nelson chooses against taking his advice. It’s as if his decades of experience are upstaged by the strong will of a preteen.

But in many forms, Hawk appreciates Nelson’s mental approach to the sport. She knows what she wants, and while she’s focused on daily improvement, she isn’t afraid to say no — not even to him.

“She is fiercely determined and dedicated, almost to a fault in terms of she will not give up,” Hawk said. “There are times when I try to tell her things, basic trick suggestions: Hey, maybe you should try to learn … ‘I don’t like them.’ This could be something you go to as a backup. If you lose speed, you … ‘Yeah, I don’t want to do that.’

“But I have helped her learn a couple of tricks. I will take credit for that.”

@reese__nelson 🌪️ #padup #187killerpads pic.twitter.com/oUEcYRL45X

— 187KILLERPADS (@187KILLERPADS) May 28, 2024

The middle child of three, Nelson brings a varied personality to the table. She loves Eminem and will vibe to his tracks when she tries to get into a zone. When she’s watching television, she loves the Netflix reality series “Nailed It!” as well as other baking shows.

Nelson has been homeschooled in previous years but is excited about in-person seventh grade in the fall. It’ll be the first time in years that she returns to schooling with other students.

When asked what’s more nerve-racking between starting middle school or landing 540s and 720s, she didn’t hesitate to respond.

“Going to middle school,” she said. “I mean, like, I’m nervous.”

When she arrives at her new school, she’ll have tons of stories to tell. Nelson lives a cool-yet-unorthodox life that some may think is as complicated as one of her gravity-defying attempts at a skate park. Even her mother calls her life “strange,” but that’s far from a diss. If anything, it’s the ultimate compliment.

How many people can say they know Hawk? How many can call or text the skateboarding icon at any hour? And how many, regardless of age, can say they’ve skated with Hawk and Beastie Boys member Ad-Rock on the same day — and treat it as “just another day?”

“Tony was like, ‘Hey, you want to come skate with Ad-Rock from the Beastie Boys?’” said Bedier, a fan of the Beasties. “Reese was like, ‘OK.’ And I’m like … ‘What?!’

When Nelson isn’t skateboarding, she’s studying her personal favorites: Tom Schaar, the first to land a recorded 1080 (three revolutions), and Colin McKay, a fellow Canadian.

Nothing personal against Hawk, right?

“Tony is good, but I really like Tom Schaar’s skating. He’s strong and aggressive,” Nelson said. “Colin’s like that, too. Tony does good tricks, though.”

Nelson also keeps an eye on another youth skateboarder making news as of late. Arisa Trew, a 14-year-old from Australia, last month became the first-ever female skateboarder to successfully land a recorded 900. Trew is ranked the No. 2 female park skateboarder in the world, according to World Skate, and her 900 came 25 years after Hawk landed the trick at X Games V in San Francisco.

“She works hard. She’s good,” Nelson said of Trew. “I haven’t really thought about trying (the 900).”

ICYMI … The legacy of the 900 continues!

History has been made again and the similarities are uncanny.

First @tonyhawk landed the World’s First 900 at X Games 1999, now Arisa Trew has become the first woman to land a 900 on a skateboard.

The torch has been passed. pic.twitter.com/0NqYlB9kAH

— X Games (@XGames) May 31, 2024

Nelson is still about having fun with skateboarding rather than building the legacy her fans might push for. Hawk constantly reminds Nelson that at this stage in her life, winning isn’t everything. Though winning a gold medal would be a monumental X Games achievement, simply competing in the prestigious event should be valued.

Keeping her expectations tempered arguably is Hawk’s toughest job as mentor. Particularly when it pertains to a competitor who enjoys showing off her aggressive style and attempting moves that come with the highest degrees of difficulty. Many times, those moves are successful. Sometimes, they miss — and Nelson is her worst critic.

“She’s very hard on herself, (but) I want her to still have fun with it,” he said. “Her determination and her fierceness is almost an impenetrable wall.”

“I feel pressure, but not because other people put it on me,” Nelson added. “I put a lot of pressure on myself to be perfect and to learn everything every time. And sometimes, it doesn’t work, which is annoying.”

Having Hawk as a mentor helps to keep Nelson’s life balanced, Bedier said. Hawk has four children, so he understands the pressures Nelson goes through as a young competitor, as well as the roller coaster of emotions Bedier deals with.

Hawk’s wisest words may consistently go to Bedier more often than Nelson, primarily because of the evolution of her daughter and what’s to come if she continues excelling in the sport.

“It’s been over three years. … He’s really become somebody I can rely on for advice and support, not just for Reese’s skating, but in terms of my role as a parent, like, what I can do to support her,” Bedier said. “His advice has been invaluable. It’s not just about tricks; it’s helping us navigate the world of skateboarding.”

Sunday will be Nelson’s time to shine, and she’s ready for the spotlight. But transforming into her own version of a superhero still is more for the memories and less for the fame and fortune.

X Games will get another chance to see the innocence of a rising star. And at the same time, Nelson will have another shot at showing why people should pay attention.

“I’m one of the older guys, but we’re talking about 20-, 30-year-old veterans of vert skating watching her, and they’re completely blown away,” Hawk said. “It’s not a novelty. It’s not, ‘Oh, she’s good for her age.’ She’s just that good.”

“It’s been a wild ride the last three years, and we didn’t seek any of this out,” Bedier added. “Reese has a really good group of people around her. We definitely hit the jackpot.”

(Illustration: Dan Goldfarb / The Athletic; photos: Ric Tapia / Icon Sportswire via Getty Images, Spencer Weiner / Los Angeles Times via Getty Images and Sean M. Haffey / Getty Images)

Culture

How fast could a human being throw a fastball? 106 mph, 110 mph — even 125 mph?

The 10-second 100-meter dash. The four-minute mile. The two-hour marathon. In baseball, is the 110 mph fastball the next big number to fall? What actually is the upper limit when it comes to professional pitchers throwing their fastest pitches?

There is some debate about what the fastest fastball to date has been. In the documentary Fastball, filmmakers looked at a few key moments from the past. Bob Feller threw a ball faster than an 86 mph motorcycle. Nolan Ryan was clocked at 100.8 mph by a radar gun in 1974. If you convert Ryan’s number to the out-of-the-hand methodology used to measure pitch speed today, you get 108 mph. For some, that counts as the fastest pitch on record.

We’ve been tracking major-league pitchers with the same quality of technology since 2007, though, and nobody has thrown harder than Aroldis Chapman and his 105.8 mph fastball in 2010. So Ryan’s 108 would be a large departure from 15 years of tracking pitches — and, for what it’s worth, it’s a large departure from radar gun readings over the rest of his game that day, as well as the rest of his career, which usually topped out around 96 and 97 mph.

Some Nolan Ryan gun readings to show how random Radar gun/Laser technology was back in the day. pic.twitter.com/BAuEMAbTIM

— Rob Friedman (@PitchingNinja) January 20, 2024

Since those other pitchers were clocked using outdated technology, it’s probably fairest to call 105.8 mph the modern record in fastball velocity. So that’s how fast a human has thrown the ball. But what’s the fastest a human being could throw the ball?

“When you build up a simple physics model that is essentially a series of collisions between body parts, you get a max fastball velocity of about 125 mph,” said Jimmy Buffi, who has a PhD in biomedical engineering. Buffi is a former Los Angeles Dodgers analyst and is a co-founder of Reboot Motion, a player development consultancy firm.

“We’ll need to use new methods,” said Kyle Boddy, current Boston Red Sox consultant and the founder of Driveline Baseball, a player development lab and consultancy company. “If there is a way to continue on, it won’t be with current methods. Using the best mechanics from elite pitchers, piecemeal, is unlikely to be the way we can create the 110 mph pitcher.”

Others thought about the potential for injury in this pursuit – pitching injuries have been up with velocity, after all. Maybe we’re already at the limit?

“I don’t think people are going to be able to throw that hard,” said the Dodgers’ Bobby Miller, the league’s third-hardest throwing starter, about numbers like 110 and 125 mph. “You reach a certain point where your arm will probably break.”

That’s three different answers. Let’s take a closer look at each.

The case for 125 mph

There’s a concept in pitching called the “kinetic chain,” which describes the transfer of force from the ground, and the larger muscles in the legs, up through the core and out to the end of the arm. If you work in a purely theoretical space, that chain is basically a bunch of interactions that attempt to conserve the momentum created down low as it travels out to the arm. Buffi’s job at ReBoot is to help make those transfers as efficient as possible. He created a physics model to describe them for the purposes of answering this question.

“To come up with this toy example,” he said, “I thought of the pitching motion as essentially a series of energy transfers between two masses, similar to a large ball colliding with a smaller ball. The legs are the larger mass, and they transfer energy to the torso, which transfers energy to the upper arm, then to the forearm, then to the hand, then to the ball.”

A pitcher’s kinetic chain consists of six phases. (Graphic: Drew Jordan / The Athletic; photo of Paul Skenes: Rick Osentoski / Getty Images)

The relative sizes of each of those muscle groups govern the amount of energy that can be transferred in each interaction, just as it is in the classic physics problem in which a big ball hits a smaller ball. In the model that Buffi created, a 200-pound person putting 500 pounds of force into the ground while being 85 percent efficient in his transfers (an efficiency that is elite, but within the range of possibility, in his estimation) would throw 125 mph.

“Even though it’s a toy example, when you put in reasonable energy transfer numbers and ground reaction force values, you actually get reasonable pitching velocity estimates,” said Buffi.

One of today’s hardest throwers, Oakland closer Mason Miller, agrees that the size of the player and force into the ground was a common denominator when you look at the hardest throwers.

“Physically, I’m 230 pounds, maybe 240 at my biggest. Chapman is like 250 pounds,” said Miller. He has thrown the fourth-fastest pitch this season at 103.7 mph, which trails only a couple Chapman fastballs (one at 104) and one from Angels reliever Ben Joyce. “Force production into the ground is important, we’ve seen that from force plate testing, that’s a good measure of power production.”

But there are some flaws in this case. Ground force reactions north of the ones Buffi used have been recorded already by athletes at Driveline Baseball, and they didn’t throw 125 mph. It’s way out in front of what’s been observed, as well.

Said Miller: “125 seems like it’s way out of our current existence.”

“Oh my goodness, 125, that’s crazy,” said Twins’ closer Jhoan Duran, who has topped out at 104.8 mph.

The case for 110 mph

The study of biomechanics, or the mechanical laws relating to the movement and structure of living organisms, has unlocked velocity for a lot of today’s hard throwers. The average four-seam major league fastball, measured by the same technology and methodology, has increased in velocity every season since Major League Baseball started tracking it, all the way from 91.1 mph in 2007 to 94.1 now.

Sam Hellinger of Driveline Baseball shared an example of how this understanding of the body has helped players train to get more velocity. Justin Thorsteinson, a former Division I pitcher hoping to sign on with an organization, came to them throwing 87.7 mph in June and by August was throwing 91.5 mph, and his changing how his shoulder moved was key. Scapular retraction — in rudimentary terms, how far back the throwing shoulder reaches before coming forward — has been linked to velocity by biomechanics studies because it creates a big separation between the hip and the shoulder. As that separation snaps back like a rubber band, torso speed is accelerated, which is then transferred to the arm. That was a big focus for Thorsteinson.

“Based on Justin’s bio report, we determined that his most glaring need mechanically was his arm action, specifically his max shoulder external rotation and scapular retraction,” said Hellinger.

After some work with weighted balls and specific drills, Thorsteinson improved his scores in the specific biomechanics that they were targeting, as you can see also from this picture, which shows how much he improved his shoulder retraction.

Before (left) and after (right) for Justin Thorsteinson, showing more shoulder retraction after the drills. (Driveline Baseball)

So could a 250-pound monster of an athlete refine each of his movements to the best of current knowledge and bust past the 106 mph ceiling towards the 110 mph that Boddy thought possible?

“If you’re getting bigger than Chapman, who throws 105, if you get any bigger, you lose coordination,” said Dodgers starter Walker Buehler. “He’s as big and as strong as you can be, and his delivery is all about velo.”

Boddy is also not sure that a big dude, plus the best piecemeal mechanics of our time, was the right way forward.

“We’ll need to use new methods, like simulation of human movement with millions of synthetic data points using machine learning and artificial intelligence to explore the entire latent space of possible mechanical outputs and muscular contributions to the throwing motion,” said Boddy. “This is something Driveline Baseball has been working on for years and is rapidly becoming a priority project — primarily for durability improvements over performance gains, though we anticipate breakthroughs in both realms over the coming years from our Sports Science and Research teams.”

In other words, instead of taking our mythical 250-pound flamethrower and then giving him what modern research thinks is the best mechanics in the legs, the torso, the shoulder, and the arms, Boddy is hoping that AI could help us think of new ways those body parts could move in concert with each other, in order to identify even better possible mechanics.

Could AI do this? Given the rapid rise of that technology, it seems plausible that we could see gains from re-evaluating current processes, even ones that involve the movement of our bodies.

The case for 106 mph

Let’s flip over to a different sport for a second. Over in the 100-meter dash, we have records going back to the 1970s. If we track the best times by year, it looks like we’re hitting a bit of an asymptote — instead of large gains like we saw in the 1980s and ’90s, we’re fighting over smaller increments of change.

If you altitude-adjust these numbers — running higher up can shave some milliseconds, as we saw with a couple of record-breaking runs earlier this century — we’re zeroing in around 9.7 to 9.8 seconds as perhaps the fastest a runner can manage in a neutral setting. This is seen by some to show that modern training, nutrition, and equipment have pushed the body as far as it can go. There are similar graphs in other running sports that suggest the same.

A few examples from other sports:

100m sprint, marathon & 1 mile world record progressions pic.twitter.com/6z5nhPPbdP

— Ben Brewster (@TreadAthletics) May 28, 2024

The maximum pitch velocity seems to be following a similar trajectory in baseball. Chapman threw 105.8 mph in 2010 and since then, the average best fastball has been 104, with a peak of 105.7 (Chapman again in 2016) and a nadir of 102.2 (in 2020, of course). The best non-Chapman fastball is around 104 mph in any given season.

There are some differences between pitching and running, though. Here’s where Glenn Fleisig, the director of biomechanics research at the American Sports Medicine Institute, comes in.

“Fifteen years ago I was quoted as saying that I didn’t think top velocity or the ceiling going up, but I foresee it getting pretty crowded at the ceiling,” said Fleisig. “It wasn’t a lucky guess that I pulled out of my butt.”

“When others talk about the ceiling, they talk about physics and statistics. Maybe by the laws of physics, maybe people could throw faster. Maybe the highest number could keep going up like it (did) for runners, because the training can improve, the mechanics and biomechanics can improve, the nutrition and supplements can improve,” he continued.

“The difference here is that we’re pushing this little ulnar collateral ligament to its limit. We are strengthening our muscles and improving our mechanics and nutrition, but based on how the body is built, the ligaments and tendons don’t improve proportionally to the other parts of the body and the process.”

When that ligament tears, the pitcher needs Tommy John surgery to get back on the mound, and those surgeries are more common than ever. How much stress that ligament can handle might be up for debate.

“No one really knows how much stress a UCL can really take, because of a problem I call cadavers and robots,” said Randy Sullivan of the Florida Baseball ARMory on a recent podcast. “We determined how much stress a UCL can take through a cadaver setting where we found that it tears at 35 newton-meters of torque, and then we used motion capture to determine that it can tolerate on a single pitch, it has to accept 70-75 nM of stress. We got the bottom number from a person who wasn’t alive; living tissue wouldn’t react the same way. And we got the top number from a model, a mythical robot.”

Fleisig, who authored the study that looked at how much stress the UCL could handle in cadavers, saw that second number in a slightly different light.

Throwing high-velocity pitches puts a great deal of stress on a pitcher’s UCL. (Drew Jordan / The Athletic)

“That 70-75 nM dynamic stress from biomechanics analysis is on the entire elbow, and the UCL does about a third of that resistance, your bones and tendons help with that resistance,” he points out. Taking a third of 75 nM leaves the current stress on the elbow within the 35 nM maximum we see in cadavers.

The sport might be telling us something with the spike in arm injuries. All those torn ligaments, which are increasingly tied to top-end velocity by the best available research, seem to suggest that we are running up on the physical limits of that little tendon. Maybe 106 is all that we can do.

“I’ve thought about it before,” said Joyce, the Los Angeles Angels pitcher who has thrown the hardest this year and also had a fastball tracked at 105.5 mph in college. “I would think someone will hit 106.0, but I don’t know if there is much more than that.”

Where do we go from here?

The work to improve the ceiling will go on, no matter what injuries say, because of the reward system in place for pitchers who can throw hard. The highest draft picks, the biggest free-agent contracts — those go to the fastest fastballs, and that’s not likely to change in the short term.

Joyce has an identical twin who tops out at 98 mph, with similar mechanics and identical genes. So what separated Ben from his brother Zach?

“I didn’t do anything specific,” said the harder-throwing Joyce. “I just always wanted to throw hard, so I tried to throw harder every day, kept throwing harder and harder, and it eventually worked out.”

Joyce pointed out that he hadn’t really optimized his mechanics or done anything special in that regard. He’s just throwing 103 and 104 on pure willpower. He’s also a little smaller than Miller and Chapman. Maybe the next kid is 50 pounds heavier, has that same iron will, ends up as a reliever where he can max out on fewer pitches, and also optimizes his biomechanics. That scenario seems likely to push the top-end velocity some … but how much higher if that little ligament is taking all it can handle already?

If that combination of inputs only pushes maximum velocity forward a tick or two, it might behoove young pitchers to consider other goals as they come up the ranks. In other words, if we get to a point where everyone throws harder than 94 mph in the big leagues, but nobody really throws harder than 106, maybe the best way to stick out in the future will be to demonstrate a pitch mix with varying velocities and movements, with good command. Maybe the success of softer-throwing pitchers such as the Royals’ Seth Lugo, who throws eight different pitches from two different arm slots, and the Phillies’ Ranger Suárez, who keeps the ball on the ground with great command, can provide new role models for young pitchers.

As the injuries mount in the search for velocity, chasing a maximum number that might not even be possible may not be the best plan for a young arm interested in making the most out of his talent.

— The Athletic’s Sam Blum contributed to this story.

(Top image: Dan Goldfarb / The Athletic; Photo of Paul Skenes: Justin K. Aller / Getty Images)

Culture

He's 15 and just made his PGA Tour debut. Miles Russell won't be the last

DETROIT — Miles Russell’s pants don’t fit. He didn’t mean to show off his ankles during Thursday’s first round of the Rocket Mortgage Classic. It’s just, the inseam he was measured for recently no longer applies. He hit a growth spurt soon after and now measures 5-foot-7, but stuck with pants meant for a wee 5-6. His waist, meanwhile, remains near-nonexistent. At 120 pounds, he wears a 28-inch waistline “with a scrunched belt.”

So there was Russell on Thursday, walking around Detroit Golf Club, flashing those ankles with each step.

Such is the life of a 15-year-old.

Russell made his PGA Tour debut at the Rocket Mortgage, shooting a 2-over 74. Born in 2009, he signed autographs for 7-year-olds, 10-year-olds, 15-year-olds and some adults. He took every swing with a PGA Tour Live cameras a few feet behind him. He held a press conference the day before his first round and afterward. He played from tees measuring 7,370 yards. He played in a field with 10 of the top 50-ranked players in the world.

And the strangest thing about it all?

It felt oddly normal.

This year has already seen two 16-year-olds make the cut on the PGA Tour — Kris Kim at The CJ Cup Byron Nelson, and Blades Brown at the Myrtle Beach Classic. Last year, 15-year-old Oliver Betschart survived a 54-hole qualifier to play in the Bermuda Championship, becoming the youngest player to play in a PGA Tour-sanctioned event in almost a decade. He was three months younger than Russell is now.

First birdie on TOUR for 15-year-old Miles Russell 🤩 pic.twitter.com/5tLfnf5HuW

— PGA TOUR (@PGATOUR) June 27, 2024

Now it’s Russell at the Rocket Mortgage. In April, he played in the Korn Ferry Tour’s LECOM Suncoast Classic, shooting rounds of 68 and 66 to become the youngest player to make the cut in the developmental tour’s history. Headlines followed. Then Russell followed with rounds of 70 and 66 to finish T20. The winner, Tim Widing, was 11 years older than him.

Tournament organizers from the Rocket Mortgage took notice and contacted Russell following his performance at the Suncoast Classic, hoping to capitalize on the story. Because that’s what a tournament like the Rocket desperately needs — attention, however it can get it. Big names are scarce in Detroit, so compelling storylines are required. The Nos. 2, 4 and 5 ranked amateurs in the world — Jackson Koivun, Benjamin James and Luke Clanton — are all in this year’s field. Clanton is making his PGA Tour debut, as is Neal Shipley, the low amateur at the Masters and U.S. Open who recently turned pro. As Shipley walked off the course on Thursday, he was told next week’s John Deere Classic, another non-elevated PGA Tour event, has a spot for him.

Those names are all at least in or out of college, though.

Russell just finished his freshman year of high school, even though he doesn’t attend a physical school. The Jacksonville Beach, Fla., native began playing at 2 years old, broke par at 6, and has been on a prodigious path ever since. He is home-schooled and already operating as a small business. He has an agent and holds Name, Image and Likeness (NIL) deals with TaylorMade and Nike.

Because 15 sounds so jarring, there’s the tendency for some to see Russell as a novelty.

In reality, this is all less and less uncommon.

Russell did not come to Detroit like some kid looking to high-five his heroes.

Rico Hoey, one of Russell’s playing partners on Thursday, was on the practice green after their round and still in a bit of disbelief. Now 28, he was trying to break 80 at Russell’s age. Coming into the first round, he assumed he and Pierceson Coody, a 24-year-old PGA Tour rookie with three Korn Ferry wins to his name, would need to keep things light and easy for the young star. Then they met him.

“As a 15-year-old, I’m sure I’d be pretty nervous out here, so we tried to make it easy on him, and make him feel comfortable, but, really, I don’t even know how much he needed that,” Hoey said. “He was cool. His short game is really good. He has a lot of length for his size. His game is just really good and he’s really calm.”

Russell shot a 74 in his first PGA Tour round on Thursday. (Raj Mehta / Getty Images)

Some will always be inherently uncomfortable with young mega-watt talent being expedited to play among pros in any sport. But that’s never stopped it from happening. And golf appears to be revving more and more, and going younger and younger. It’s reasonable to expect someone soon emerging to surpass Michelle Wie West as the youngest player to ever tee it up in a PGA Tour event. She was 14 years, three months and seven days old when she played in the 2004 Sony Open.

What’s most eye-opening isn’t the ages, but how narrow the gap is between the kids and the pros. Russell is not some beefed-up bomber. He is instead elastic and has crafted a swing with his coach, former Korn Ferry player Ramon Bascansa, that generates enough clubhead speed to hang with the pros. He averaged 292 yards off the tee on Thursday, tied for 78th in the 156-man field.

But that doesn’t mean everything surrounding him isn’t still misfitting. He is technically not old enough to use Detroit Golf Club’s men’s locker room, though exceptions are made this week. He is not able to drive, let alone rent a car or check into a hotel alone. One group behind Russell’s, 36-year-old Rafael Campos played his round while ripping a few cigarettes — a vice that Russell can’t legally buy for another three years.

Afterward, Russell played along with questions about the experience, but was really only concerned with the golf. He talked about unforced errors and missing some makable puts. He said he learned watching Coody and Hoey how tour pros manage to “grind it out and shoot a couple under.” He said, sure, he was nervous to start the round. How much out of 10? “I’d probably give it a seven.” But sort of shrugged off the idea of being intimidated.

Russell’s voice was soft and he was obviously still a little peeved. A missed 3-footer on the final hole left him with a closing bogey.

“We live, we learn, we move on,” he said, sounding like someone who is not only used to playing on tour, but damn near expects to.

Maybe, for better or worse, that’s not so crazy anymore.

(Top photo: Raj Mehta / Getty Images)

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoTracking a Single Day at the National Domestic Violence Hotline

-

Fitness1 week ago

Fitness1 week agoWhat's the Least Amount of Exercise I Can Get Away With?

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoSupreme Court upholds law barring domestic abusers from owning guns in major Second Amendment ruling | CNN Politics

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoTrump classified docs judge to weigh alleged 'unlawful' appointment of Special Counsel Jack Smith

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoSupreme Court upholds federal gun ban for those under domestic violence restraining orders

-

World5 days ago

World5 days agoIsrael accepts bilateral meeting with EU, but with conditions

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoTrump VP hopeful proves he can tap into billionaire GOP donors

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoInfluencers and politicians – meet the most connected lawmakers